A Brazilian technological innovation will be used in the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE), which is a multibillion dollar project led by Fermilab, the leading particle physics laboratory in the United States, and is expected to be operational by the end of this decade. With the support of other research institutions and national companies, a team of physicists from the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) has developed a filtering method that removes impurities commonly found in liquid argon: nitrogen atoms.

When argon, which is a noble gas at room temperature, is maintained in chambers at -184°C, it becomes a liquid and can be used to achieve the following main objective of DUNE: to detect neutrinos, which are mysterious subatomic particles that have almost no mass, no electrical charge, and very little interaction with any material. Because of its relatively heavy atomic nucleus, argon is more likely to interact with neutrinos; these neutrinos are the second most abundant particles in the universe after photons (particles of light).

Liquid argon chambers are the most advanced way of detecting neutrinos. A larger volume correlates to a greater probability of interacting with the particles. For this reason, DUNE has four pools, each containing 17,000 tons of liquified argon. However, a number of contaminants in the tank could affect the experiment. The three most common contaminants are oxygen, water, and nitrogen. Effective molecular filters exist for the first two types of contaminants. However, filters are not available for nitrogen. Nevertheless, an invention was recently developed by a Brazilian team to address this issue.

Contaminants are generally found at levels of less than 10 parts per million (ppm); this amount correlates to very few micrograms in each gram of argon. “This level of impurity makes it impossible to carry out the experiment, and liquid argon of a higher purity is not available on the market,” explains physicist Pascoal Pagliuso, head of the UNICAMP group that developed the new method. “DUNE requires very few molecules of impurities, in parts per trillion.”

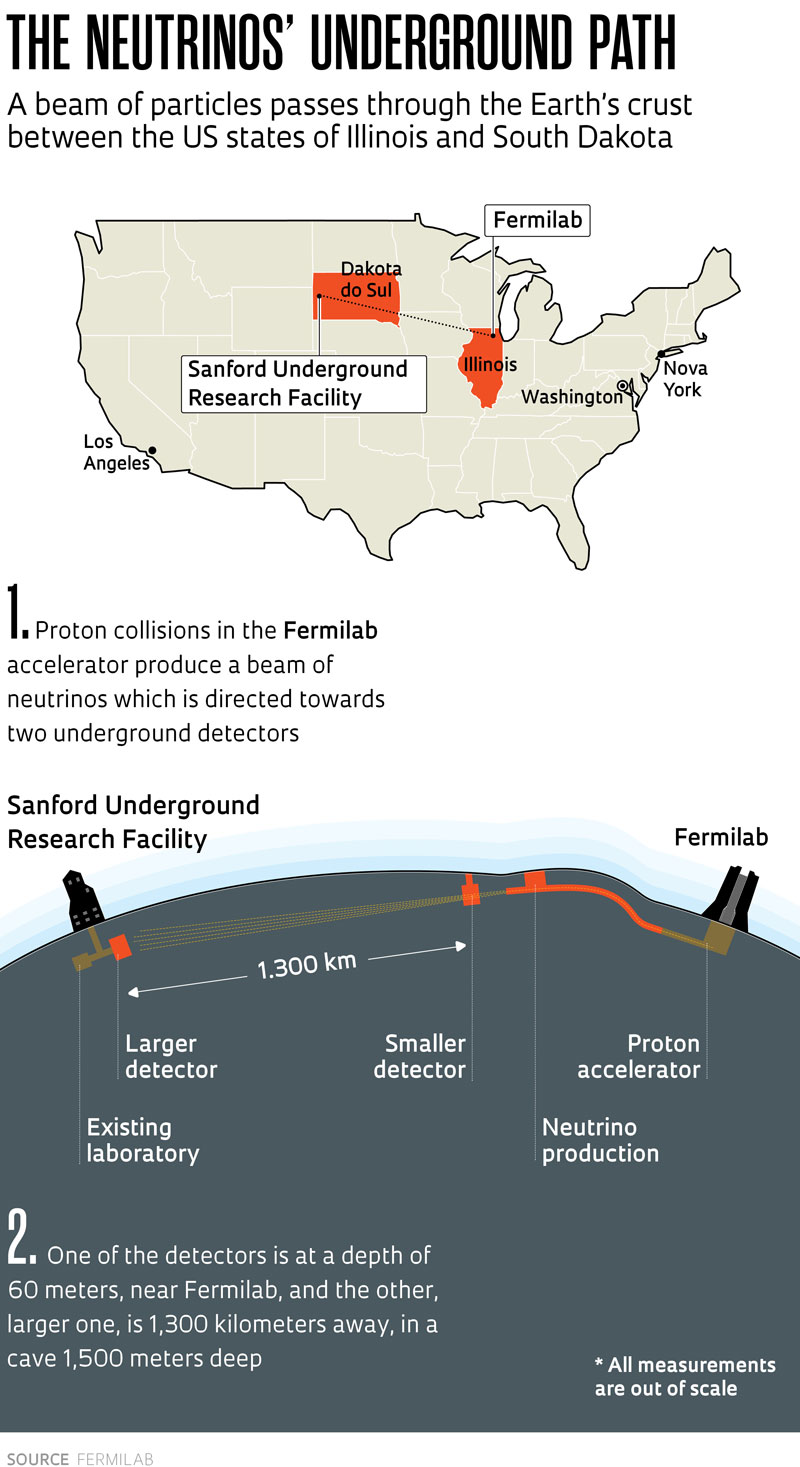

DUNE is the largest neutrino experiment undrway, with a cost of US$3.3 billion. DUNE consists of a facility (the Long Baseline Neutrino Facility, LBNF) located at Fermilab and two detectors separated by a great distance; this facility is dedicated to producing a beam containing trillions of neutrinos. DUNE begins at Fermilab’s particle accelerator in Batavia, which is on the outskirts of Chicago, Illinois. Proton collisions produce smaller particles, which decay and create other particles. Neutrinos are among the byproducts of these collisions and transformations of matter that occur in the accelerator. The LBNF is responsible for collecting the beam containing only neutrinos and sending this beam underground to the two detectors.

The first and smallest detector will be located next door, near the neutrino source at Fermilab, in a shallow cave, 60 m deep. The second, and much larger detector will be located 1,300 kilometers away inside an old abandoned mine in Lead, which is a town in the state of South Dakota. The Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF) is currently located at this location and will house the detector in a cave that is currently being excavated 1,500 m underground. The facility is designed to prevent the neutrino beam in South Dakota from being disturbed by cosmic rays and neutrinos from space and surface disturbances.In 2020, with support from FAPESP, Brazilian researchers began developing an efficient method of purifying argon using a porous molecular sieve called a zeolite, which is based on the mineral aluminosilicate (composed of aluminum, silicon, and oxygen). The basic research that led to this technology originated from a study by Pagliuso’s team at UNICAMP that focused on the differences between nitrogen (N₂) and argon (Ar) and their response to the application of an electric field.

The practical aim of their study was to find a zeolite that could absorb (through adhesion or fixation) only the nitrogen atoms without absorbing the argon atoms. Dilson Cardoso, a chemist at the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar) who specializes in zeolites, was essential in this pursuit. Computer simulations were carried out for materials that could be used as filters to separate nitrogen from argon. “The modeling allowed us to determine how argon circulation and purification systems behave, providing data that would help us design various parts of the system,” explains chemical engineer Dirceu Noriler, from UNICAMP. “We obtained information on the filters’ saturation time, the number of purifiers needed, and the number of cycles needed to achieve the desired purity.”

The most promising materials were then tested on a small scale in a controlled supercold environment. To this end, UNICAMP uses a liquid-argon purification test cryostat (PuLArC). This equipment was made of stainless steel, was capable of holding 90 liters of liquid to be purified and was built by the companies Equatorial Sistemas and Akaer. The team also used their experience at the cryogenic laboratory at the Brazilian Center for Research in Physics (CBPF) in Rio de Janeiro. The cryostat was similar to a double-walled thermos with a vacuum in the middle. This prevented the environment’s temperature from affecting the temperature inside the container.

According to materials engineer Fernando Ferraz, who is Akaer’s vice president of operations, the experiment enabled the creation of 3D models of the entire purification plant. “We carried out comprehensive simulations of the transport process, assembly, and installation of all necessary equipment for one of DUNE’s laboratories,” says Ferraz. “The process of controlling the purity of argon requires filtering cycles in the liquid and gaseous states, regeneration, and condensation.”

The results from the PuLArc tests were published in August 2024 in the Journal of Instrumentation. According to the publication, a filter made of a material known as Li-FAU, which contains lithium in addition to aluminosilicate, was the most efficient at capturing nitrogen molecules in liquid argon. With its use, the contamination in 100 liters of argon, which was initially between 20 and 50 ppm, was reduced to between 0.1 and 1 ppm in less than two hours. The filter was also tested by the DUNE team in a larger 3,000-liter tank, and the results were equally good.

Ryan Postel / Fermilab DUNE experiment cave in an old South Dakota mine where one of the neutrino detectors will be locatedRyan Postel / Fermilab

The Li-FAU-based process is currently in the final stages of testing at ProtoDUNE, which is the prototype for DUNE at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), on the France-Switzerland border. At this location, the amount of liquid argon to be purified exceeds several tons. The new process has been patented and could be used for other purposes in the future. The process appears to be versatile and has the potential to be used to purify other gases, perhaps carbon dioxide, and liquids on an industrial scale.

The filter used to remove the contaminants from liquid argon is the second major contribution stemming from Brazil’s participation in DUNE, which has attracted 1,400 scientists and engineers from 200 institutions and 35 countries. The first contribution was a photon trap that captures the flashing light produced by the interaction of neutrinos with the argon atoms. Invisible to the human eye, the light has a wavelength of 127 nanometers. By storing these data, the trap enables researchers to examine the properties of neutrinos and reconstruct their trajectory in three dimensions. The device, called X-Arapuca, was created in the middle of the last decade by physicists Ettore Segreto and Ana Amélia Machado from UNICAMP. Its latest version, 2.0, is already in use in the United States.

The neutrinos generated at Fermilab will travel through the Earth’s crust and reach the liquid argon tanks. The interaction with argon will release electrons and produce flickers of light. A uniform electric field will direct these electrons toward the electron detectors. The photons produced by the scintillations will then be captured by the X-Arapuca traps. “The photons produced in the scintillation allow me to calculate when the neutrinos arrived, which direction they came from, and how they interacted with the argon,” explains Machado. We still do not know the mass of each of the three known types of neutrinos—muon, tau, and electron—or why they oscillate with each other as they move.

At the Sandford Research Center, where DUNE’s largest detector will be located, at least two of the experiment’s four modules will have X-Arapuca traps. These traps will form a photodetection system around the liquid argon pools. With funding from FAPESP, Brazil will be responsible for building some of the components and assembling and installing 6,000 X-Arapuca traps in one of the DUNE modules by the start of data collection, which is scheduled for 2029. “The biggest challenge will be to coordinate the process of building the traps in Brazil and receiving the rest of the components from abroad, without jeopardizing the experiment’s schedule,” says Segreto. “In Brazil, we will produce the mechanical parts and the optical filters, which are the most important elements for the device to function.”

According to Sylvio Canuto, a physicist at the University of São Paulo (USP), investing in DUNE is important because DUNE has the potential to reveal details on neutrinos and, by extension, the formation of the universe. One of the most intriguing questions is why there are more particles than antiparticles in the cosmos. “In theory, we expected particles and antiparticles to have been created in the same proportion at the beginning of time. But, today, we see that the universe is mostly made up of particles. The origin of this mystery is attributed to the role of neutrinos, and today we are closer to unravelling it,” says Canuto, who has followed Brazil’s participation in DUNE since the beginning of the project and is an advisor to FAPESP’s Scientific Directorate. The next step, according to the USP physicist, is to ensure Brazilian participation in the work of analyzing the data generated by DUNE to create a reference center in the country for Latin America.

Published in October 2024

Projects

1. Advanced instrumentation for large collaborations in high-energy physics: Air purification and photodetection for LBNF-Dune (n° 24/07128-7); Grant Mechanism Research Grant ‒ Special Projects; Principal Investigator José Pagliuso (UNICAMP); Investment R$84,484,851.05.

2. Light detection system for the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (n° 21/13757-9); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Principal Investigator Ettore Segreto (UNICAMP); Investment R$17,916,736.09.

3. Light detection system for the Dune-X-Arapuca experiment (n° 19/11557-2 ); Grant Mechanism Young Investigator Award; Principal Investigator Ana Amélia Bergamini Machado (UNICAMP); Investment R$2,992,720.82.

Scientific article

CARDOSO, D. et al. Innovative proposal for N2 capturingin Liquid Argon using the Li-FAU molecular Sieve. Journal of Instrumentation. Vol. 19. Aug. 2024.

Republish