Almost daily, geographer Davis de Paula, of Ceará State University (UECE), walks the shoreline of Fortaleza, the state capital, and the neighboring city of Caucaia. Examining the beaches, he concluded that Fortaleza’s 16 groins — elongated structures made of rock blocks that extend tens or hundreds of meters into the sea, built from the 1960s onwards to contain rising seawater — have caused intense erosion on the neighboring city’s beaches.

At one of the beaches, stretching over 680 meters (m) in length, the coastline, which marks the boundary with the sea, has receded by 31 m, at an annual average rate of 1.8 m per year, from 2004 to 2021. More recently, from May 2021 to January 2022, the phenomenon intensified, and the coastline receded by 2.9 m. Almost 90% of the assessed stretch of shoreline was in a continuous process of erosion, as detailed in the study co-organized by de Paula and published in 2023 in the scientific journal Earth Surface Processes and Landforms.

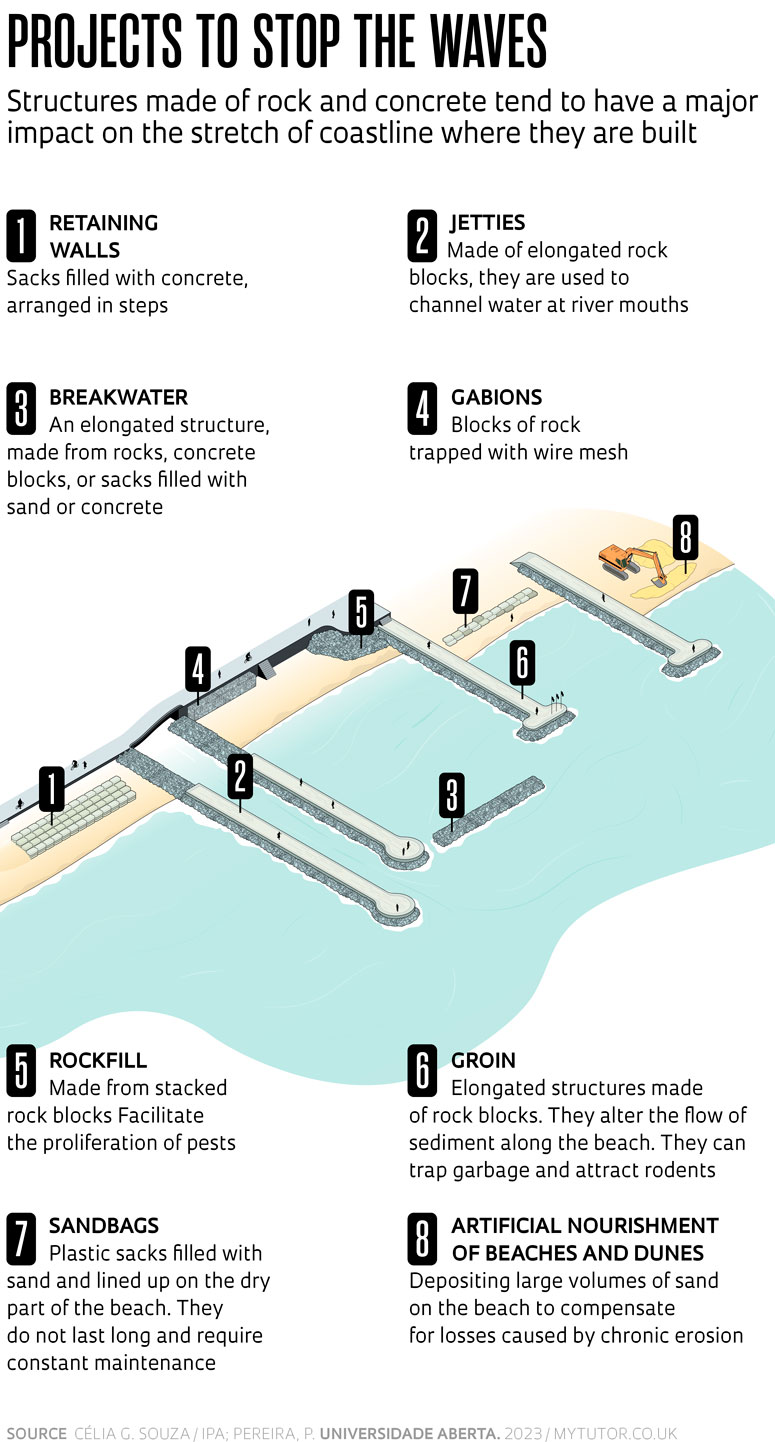

Caucaia’s city council erected retaining walls in places where sand was continuously being lost. It didn’t work. These rigid barriers amplify wave strength, change the sea currents, and can cause beaches to disappear, even miles from where they are built (see infographic).

Now, the city’s government announced a plan to build 11 groins at three tourist beaches, at a cost of R$44 million. “In addition to groins, we need land-use planning guidelines that establish the areas that can and cannot be occupied by houses and streets,” says de Paula.

Built decades ago, along the Brazilian coastline, groins, retaining walls, breakwaters, and other structures that seek to protect houses and streets from rising seawater, with their benefits and limitations, are becoming more necessary in the coming years. Coastal erosion, which has already changed 60% of the Brazilian coastline (see Pesquisa FAPESP issues 92 and 274), is likely to get worse as climate change tends to make storms stronger and waves higher.

In the Southeast, rough, rising seas, known as a storm surge, and usually accompanied by strong wind and rain, have become more frequent. Geologist Célia de Gouveia Souza, of the Environmental Research Institute (IPA), recorded 279 severe weather events from 1928 to 2021 on the São Paulo coast. The number of storm surges, with waves over 2.5 m, increased 19% from 1928 to 1999. In the following two decades, the increase was 80%.

Results fall short of expectations

In general, due to a lack of consistent studies on their likely effects, coastal protection projects don’t usually work as desired to stop the rising sea — and often need to be remedied. The city of Fortaleza, for example, had to increase the area of Iracema beach by 40 m in 2019 after having expanded the beach by 80 m in 2000.

“Unsuccessful projects, common all over Brazil, are the result of public mismanagement, where they either fail to abide by the law or adopt the wrong guidelines from the municipal master plan,” comments biologist Marinez Scherer, of the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC). “Coastal work is planned by the municipal or state government and generally authorized with a simplified impact study, which fails to consider what could happen to neighboring beaches.”

As general coordinator of Coastal Management and Marine Spatial Planning for the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change (MMA), Scherer works to revitalize the coastal management mechanisms shelved by the previous administration, including new versions of the federal action plan (the most recent is for 2017 to 2019) and the national coastal management plan (from 1974).

“The beaches are areas of conflict,” summarizes de Paula. It is common for coastal residents to build their own seawalls and occupy dunes. At the same time, they pressure the city government to expedite containment projects and stop the seawater from entering their property.

In 2010, several houses along a beach in Florianópolis collapsed after a strong storm surge. Pressured by the residents, the city built rock barriers. The water stopped entering the houses, but the sand on the beach has receded and the water now crashes directly into the rocks. “The erosion was episodic. They didn’t need to do anything. The sand would return naturally,” says oceanographer Pedro de Souza Pereira, of UFSC. For this reason, experts consider it important to differentiate between episodic erosion, such as this, caused by isolated events, which can resolve itself, and the continuous loss of sand, which requires more attention.

Environmental scientist Mirella Costa, of the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE), says that former coconut farms in the south and north of the state were turned into allotments in the 1980s, and the houses encroached on the beach’s vegetated areas beyond each plot. “Those who had plots of land measuring 30 m by 30 m built on 30 m by 60 m, installing a pool where the dunes used to be. But the dunes acted as a stockpile of sand that the beaches use to replenish themselves,” she says. “If everyone had respected the limits, protection projects would not be as necessary today.”

Carlos Fioravanti | Léo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FapespIn Maceió (left), rock barriers to contain the rising sea, contained in Guarujá (right) with preserved dunesCarlos Fioravanti | Léo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa Fapesp

Assessing erosion

“Before protecting houses and urban structures, we need to protect the beach, which in itself is a barrier on the mainland against the waves and the sea,” emphasizes Souza. Along the São Paulo coast, nearly 65% of beaches are at a very high and high risk of erosion; the most critical beaches are in the cities of Ilha Comprida and Iguape along the southern coast, Peruíbe, Itanhaém, Mongaguá, Santos, São Vicente, and Guarujá in Baixada Santista, and Caraguatatuba, Ilhabela, and Ubatuba, on the northern coast. The 2022–2023 version of the São Paulo Coastal Erosion Risk Map can be found on the São Paulo State Coastal Flood and Storm Surge Warning System (SARIC) platform.

The Santa Catarina coast has also been transformed considerably. The beaches have shrunk in 25 of the 29 coastal municipalities, according to a survey by oceanographer Pedro Pereira and geographer Mariana Koerich, both from UFSC, with the support of Santa Catarina Research and Innovation Support Foundation (FAPESC). Published in 2023 in Ocean and Coastal Management magazine, this study attributed the changes to urbanization and the 607 coastal works, mainly rockfills.

Scherer, of the MMA, says that in some parts of Australia’s coast, the cities use the rate of coastal erosion to define the beach’s occupancy — the most vulnerable to erosion have greater restrictions than the less vulnerable. In Brazil, this methodology is not used, but at least one study by UFPE researchers, published in January of 2023 in Revista Brasileira de Geomorfologia, proposes adopting the same policy on the southern coast of Pernambuco.

After examining the loss or accumulation of sediment on the southern coast of Pernambuco from 2003 to 2020, the group decided that “applying annual erosion rates and occupancy patterns to current legislation is an excellent instrument for supporting decisions by the public authorities, especially with regard to proper coastal management.”

One way to contain erosion is to recover or preserve the so-called buffer strip, formed by the frontal dunes, with undergrowth and shrubs. “Urban beaches must have at least a 50-meter buffer strip, which would really help contain the impact of waves and tides,” says Souza. According to her, several municipalities along the São Paulo coast have managed to stop the rising seas by restoring the dunes.

Works carried out in conjunction with experts from research centers seem to have a better chance of succeeding. In 2010, Costa, of the UFPE, participated in the Integrated Environmental Monitoring (MAI) project, coordinated by the federal government, in order to identify and fix problems caused by coastal erosion in Recife, Olinda, Jaboatão dos Guararapes, and Paulista. One of the implemented measures was dismantling a permanent breakwater constructed years ago in Candeias, a neighborhood in Jaboatão. The original structure blocked the flow of sand to the north of the municipality and to the capital of Pernambuco. “Once dismantled, sediment movement improved,” she notes.

In February of 2018, Souza knocked on the door of the then Secretary of the Environment in Guarujá, Sidnei Aranha, and pleaded: “Stop removing sand from the dunes. If you keep doing this, the beach will disappear.” Even though it was banned, sand extraction continued.

The secretary supported the idea of restoring Enseada beach but warned that it would not be easy. One of the problems was a lack of dialog and differing objectives among the municipal bodies. Months later, when he warned Souza that another secretary had commissioned a tractor to remove sand from the beach, she threatened: “If you remove sand from that beach, I will file a lawsuit with the Public Prosecutor’s Office, because that dune is a Permanent Preservation Area.” It worked and the tractor retreated.

When Aranha asked what could be done to recover the dunes, she said not to do anything, because the sand would accumulate, and the dunes would recover themselves. “In less than a year, the dunes naturally returned to their original place, restinga [coastal vegetation] has spread, and the native fauna has returned, such as the southern lapwing and the burrowing owl,” reports the geologist. With the buffer strip restored, Enseada beach withstood the storm surges and high tides that hit the São Paulo coast between February and August of 2020.

In 2002, in Sydney, Australia, where he was studying at the time, Scherer was talking about settlement on Brazil’s coastline with geologist David Chapman, of the University of Sydney. At one point, the Australian asked: “Do you know when they stopped building on the dunes in Australia? When the residents of coastal towns began suing the public managers who let them build in these places.”

Scherer advocates a similar stance in Brazil: holding public managers responsible for underestimating the risks of coastal erosion. And sometimes, this happens. In July of 2020, the city of Ipojuca, 50 kilometers south of Recife, was fined by a state agency for having authorized illegal construction work on a beach. In 2021 and 2022, a local hotel, in compliance with a court order, had to vacate an area it had taken over from a beach. “The way to reduce the impact on coastal zones is to remove or at least contain the development of houses and other illegal construction works on the beach,” concludes Costa.

Project

Storm surge and coastal flood warning system for the coast of São Paulo, focusing on the impacts of climate change (nº 18/14601-0); Grant Mechanism Public Policy Research; Principal Investigator Celia Regina de Gouveia Souza (IPA); Investment R$403,406.76.

Scientific articles

KOERICH, M. P. & PEREIRA, P. S. Assessing the impacts of coastal engineering structures on the coastline of Santa Catarina state, southern Brazil: A geospatial aproach. Ocean and Coastal Management. Vol. 245, 106858. Oct. 31, 2023.

LEISNER, M. M. et al. Long-term and short-term analysis of shoreline change and cliff retreat on Brazilian equatorial coast. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. Vol. 48, no. 14, pp. 2987–3003. Nov. 2023.

SAENGSUPAVANICH, C. et al. Jeopardizing the environment with beach nourishment. Science of the total environment. Vol. 868, 161485. Apr. 10, 2023.

SIEGLE, E. & Costa, M. B. Nearshore wave power increase on reef-shaped coasts due to sea-level rise. Earth’s Future. Vol. 5, no. 10, pp. 1054–65. Oct. 2, 2017.

SILVA, P. L. da & LINS-DE-BARROS, F. M. A alimentação artificial da praia de Copacabana (RJ) após 51 anos. Terra Brasilis. Vol. 16. Dec. 5, 2022.

Republish