Efforts by researchers from Mato Grosso do Sul to save an endangered breed of cattle in the Pantanal could result in a technology capable of making life easier for cattle breeders in general. Having created a system that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to individually recognize Pantaneiro cattle based solely on images with an accuracy of up to 99.8%, the startup KeroW, incubated at the Dom Bosco Catholic University (UCDB) in Campo Grande, is now working on adapting the algorithm to other more common breeds, such as Nelore, Girolando, and Angus. The aim is to provide an alternative to traditional identification methods, such as numbered ear tags, collars, tattoos, and branding, saving livestock farmers time and money and reducing animal suffering.

The technology was initially created by computer scientist Fabrício de Lima Weber, one of KeroW’s four partners, during his master’s degree at the State University of Mato Grosso do Sul (UEMS). He used a set of computational techniques specifically for image processing and analysis, inspired by biological processes that occur in the human visual cortex, known as convolutional neural networks (CNNs).

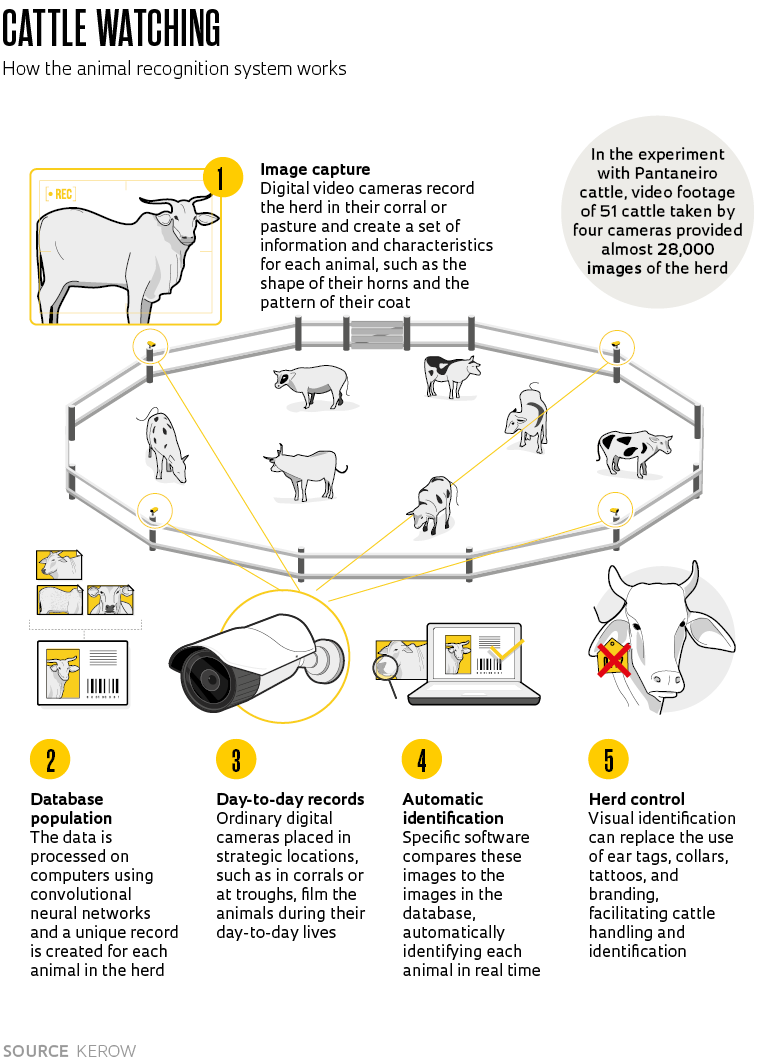

A study involving Pantaneiro cattle found that the architectural model of a CNN can be used in a computer vision system designed to automatically recognize the animals. The process is similar to human facial recognition systems already used in several countries on public transport and in stadiums and airports (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 274), where people are identified by comparing images to an existing database. The key difference is that for cattle, the cameras analyze not only the face, but also characteristics of the animal’s back, sides, and front.

An article describing Weber’s work, carried out under the supervision of veterinarian Urbano Gomes Pinto de Abreu from EMBRAPA Pantanal, and the collaboration between researchers from the UEMS Pantaneiro Cattle Conservation Center in Aquidauana (NUBOPAN), UCDB, and the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS), was published in the journal Computers and Electronics in Agriculture in 2020.

Since then, the model has been improved. “The system went through a maturation process. We adopted new technologies that are faster and require less processing power,” says Weber. “We are also automating the process. At first, everything was manual. We chose the images, separated them, and populated the database. Now the algorithm should do all of that.”

To populate the database for the Pantaneiro cattle, the researchers used four cameras placed at different locations in a corral. The cameras took thousands of pictures of a herd of 51 cattle. After the capture stage was completed, a camera equipped with special software was able to individually identify each animal in the group within just a few seconds (see infographic below).

Automatic visual recognition of the cattle facilitates herd management, allowing the history of each animal to be tracked and ensuring traceability. Information such as an animal’s location of origin, vaccines it has been given, medical history, and feed type are all available to potential buyers and suppliers, reducing the risk of irregularities in the production and sales processes.

Various computational architectures using CNNs and deep learning have already been used in studies to identify diseases in plants, classify marine organisms and objects found in the ocean, and even for facial recognition of pigs. There is, however, little research into identifying cattle using this technology, according to the researchers.

“Studies on visual identification of cattle are being conducted around the world. The ones we know of use technology supported by more advanced cameras, which is a more expensive method, while some aim only to identify the faces of the animals, which makes the process more difficult,” says Weber.

“In Brazil’s extensive beef cattle system, especially with zebu cattle like the Nelore breed, the animals rarely stand still for long enough to obtain a facial image. This is the biggest challenge: achieving not just facial recognition, but identifying cattle based on other characteristics while they’re in the pasture or corral,” explains Abreu, from EMBRAPA.

The team from Mato Grosso do Sul intends to make the technology accessible to everyone, from the largest companies to the smallest ranchers, and for it to work in the field even without an internet signal. Data could be accessed via an intranet or using a system based on wireless communication protocols such as bluetooth, both of which are low cost.

“We want to reach not just major producers, but also small rural entrepreneurs, so that everyone can use this technology. The unique aspect of our system is the cameras. While most similar systems use 3D cameras, we use 2D cameras, which are much more accessible and cheaper,” says Weber.

EmbrapaThere are only about 500 purebred animals left in the country, according to estimatesEmbrapa

Alexandre de Oliveira Bezerra, a veterinarian and livestock breeder from Rio Verde in Mato Grosso do Sul, is eagerly anticipating the results of the research. “This system would help a lot, especially by saving time spent identifying animals.”

He explains that traditionally, animals have to be held in a cattle chute to be branded with a hot iron or have a tag or collar fitted, which requires significant time and manpower. “Identifying animals by image would be great because then they wouldn’t need to be contained and marked individually. The camera alone would do the job while the cattle are in the pasture,” he says.

Bezerra claims the technology could also offer economic and health advantages. “The costs of the process could fall. Although the products conventionally used for animal identification have a low unit value, the total amount can be significant, depending on the size of the herd. Remote visual recognition would also eliminate some common problems, such as inflammation of the ears, lost tags, and data-reading errors.”

The KeroW team does not yet know when the new technology will be launched on the market. “We’re relying on investments to complete the product,” says systems analyst Vanessa Aparecida de Moraes Weber, one of the startup’s founders and a technician at UEMS. “The company recently won funding to develop a solution for Girolando cattle through a public call for proposals issued by the CNPq [Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development]. We are submitting the project to other programs in search of further funding to purchase the equipment needed to continue our research.”

In addition to animal identification, the startup plans to add body-mass estimation based on the images captured. The method was studied by Vanessa Weber—Fabrício’s wife—as part of her PhD in Environmental Sciences and Agricultural Sustainability at UCDB. Technologies designed to estimate weight using computer vision are also being studied by several agritechs and universities (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 284).

“What makes my PhD research different is that we use 2D cameras with RGB sensors [which capture color images, like humans are used to seeing], which are more accessible, cheaper, and easier to maintain,” Venessa Weber says. “At KeroW, we want to utilize the mass estimation functionality to make certain decisions, including the right time to slaughter an animal. It will also be possible to categorize animals and automatically classify them according to their weight gain.”

Pantaneiro cattle

A cross of breeds brought to the country hundreds of years ago, the Pantaneiro cattle is now under threat of extinctionThe Pantaneiro breed was first created from the crossbreeding of 11 Portuguese and Spanish breeds brought to South America by colonizers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Over generations, via natural selection, the breed adapted to the local environment and climate conditions, such as seasonal floods and prolonged droughts.

Today, Pantaneiro individuals are highly diverse, with up to 17 different types of horns, 47 coat variations, and 14 other potentially distinct features. More recently, however, uncontrolled crossbreeding with other breeds, mainly Zebu, has led to near extinction of the Pantaneiro cattle.

In a scientific article published in the journal Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, Brazilian researchers estimated that only about 500 pure specimens of the breed remain. In 2017, the Pantaneiro cattle was recognized as cultural and genetic heritage of Mato Grosso do Sul. Research and teaching institutions are now promoting breeding centers to preserve this genetic heritage.

Scientific articles

WEBER, F. L. et al. Recognition of Pantaneira cattle breed using computer vision and convolutional neural networks. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. vol. 175. aug. 2020.

WEBER, V. A. M. et al. Cattle weight estimation using active contour models and regression trees bagging. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. vol. 179. dec. 2020.

Republish