“Final idylls: finding a beautiful palm tree in Africa and enjoying the eternal sleep in its shade,” wrote André Rebouças (1838–1898) to Alfredo Maria Adriano d’Escragnolle Taunay (1843–1899), the Viscount of Taunay, on February 22, 1892. The engineer and abolitionist had not yet taken the cargo liner Malange, which would take him from Marseille, in France, to Lourenço Marques, in Mozambique, but he was already building dramatic expectations for his trip throughout the African continent.

The message is one of the 193 notes Hebe Mattos, from the History Graduate Department and Program at the Federal University of Juiz de Fora (UFJF), compiled in Cartas da África – Registro de correspondência: 1891-1893 (Letters from Africa – Records of correspondence: 1891–1893). Despite the title, Rebouças began working on the book while staying in the French resort of Cannes, where he was alone after an initial period in Lisbon, Portugal, hosted by the imperial family, with whom he would later live in exile after the Proclamation of the Republic in Brazil. Being close to Don Pedro II, he remained faithful to the monarchy after November 15 (date of the proclamation).

In France, disappointed with the course of the newborn republic, while preparing himself to circumnavigate the African continent, he wrote letters to friends, such as José Carlos Rodrigues (1844–1923), one of the owners of the Jornal do Commercio newspaper. In these letters, the first that appear in his book, the two faces of Rebouças are brought together, which also alternate in the messages written to another 25 recipients—the engineer, who reveals his ideas on infrastructure, and the intellectual, sharing his opinion on various aspects of politics.

The title, devised by the publishing company Chão, is the beginning of a series of five books compiling the abolitionist’s intimate written notes, and organized by Mattos — two of them in partnership with Robert Daibert, a fellow student at UFJF.

Mattos’s first contact with Rebouças’s letters in exile was 15 years earlier. During research for her doctoral thesis at Fluminense Federal University, she had studied black intellectuals “who somehow reflected on the memory of slavery,” she mentions. Among these, Antônio Rebouças (1798–1880), advisor of the Empire, and his son André. During the research, she took pictures of the letters written by André and kept them at the Joaquim Nabuco Foundation, in Pernambuco. In the years that followed, however, the philosopher did not get much coverage in the media, except for a few articles. But that was only until the publisher proposed to disclose the letters. “My goal shifted into sharing André’s work with a larger audience.”

According to Ligia Fonseca Ferreira from the School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Humanities of the Federal University of São Paulo (EFLCH-UNIFESP), Guarulhos campus, this type of work has not yet been developed much by Brazilian scholars. Hence the importance of granting access to Rebouças’s full text — earlier, the major source of his personal writings was a compendium from 1938. Ferreira talks about his own experience with Luiz Gama’s works (1830–1882) — an abolitionism pioneer whose writings were published in Com a palavra, Luiz Gama (With the word, Luiz Gama) (Imprensa Oficial do Estado de São Paulo, 2011) and in Lições de resistência (Lessons in resistance) (Edições Sesc, 2020).

While Gama, a former slave, was always aware of his Africanness, Ferreira believes the period addressed by Mattos is when Rebouças realized his condition as a Black person. In fact, Mattos mentions in the introduction that, in the opening letter of the book, Rebouças refers to himself for the first time as “the Black man André.”

Archives of the Joaquim Nabuco Foundation / Brazilian Ministry of EducationA letter written by Rebouças to his friend Rangel da CostaArchives of the Joaquim Nabuco Foundation / Brazilian Ministry of Education

In Mattos’s doctoral thesis, the suppression of the intellectual experience of free Black persons during the nineteenth century was a core theme. In her opinion, it is a “basic point for the way racism was institutionalized as not racism.” “Color is mentioned when one speaks about a slave, a suspect. Trafficking involves Black people. Whenever someone mentions a Black person, a “negro” or a “creole,” they have a slave in mind.” Intellectuals, however, had no color, although, as explained by the author, during the nineteenth century, over 70% of the population were Blacks or browns. Even researchers ignored the racial details when talking about men who today have major streets named after them, such as André Rebouças, or another engineer, Teodoro Sampaio (1855–1937).

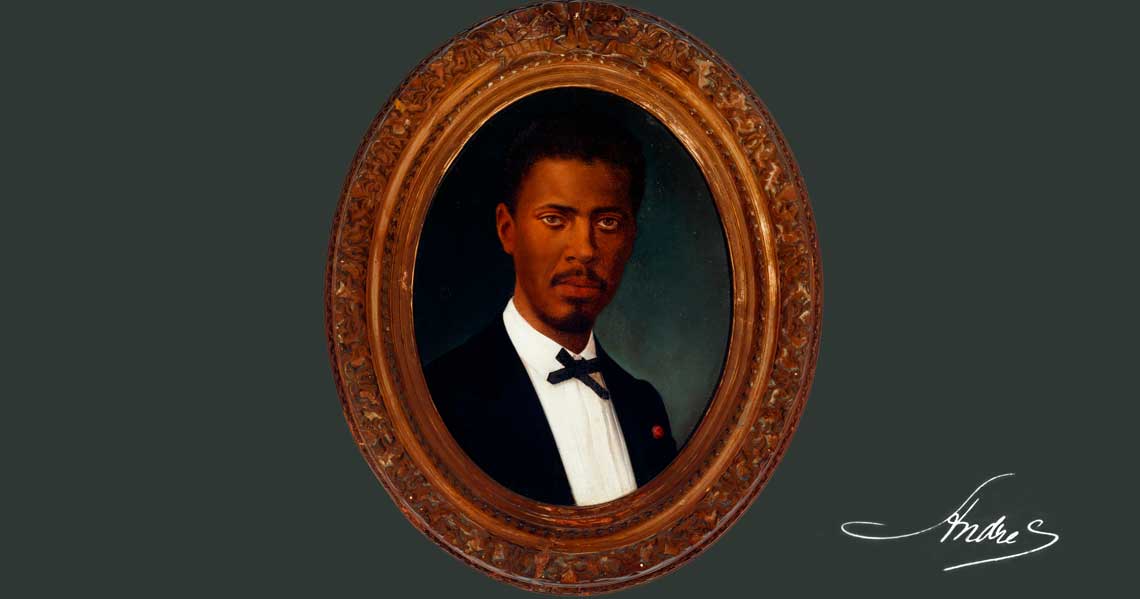

This whitening, mentions the author, was reinforced by the black and white photographs that lighten the skin of many of these people — but not that of Rebouças himself, whose skin tone cannot be concealed in portraits. According to Mattos, the sharpness of his color enhances the myth of racial democracy. When speaking of Rebouças as an important Black man, one of the most noteworthy aspects, she confirms, was his friendship with the emperor, as if his path as an engineer and entrepreneur tailoring commercial relationships with other men of his industry in several countries, “were a result of a grant” by the monarchy.

Angela Alonso, from the Department of Sociology of the School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Humanities at the University of São Paulo (FFLCH-USP) and member of the adjunct panel of the FAPESP Scientific Board, also highlights the “nullity of the racial issue” and how much Rebouças was used for that purpose, largely the “spurious association” between himself and the monarchy. Pursuant to that connection, “Rebouças has not been praised as a Black hero,” she shares.

For the author of Flores, votos e balas (Flowers, votes, and bullets) (Companhia das Letras, 2015), in which abolitionism is addressed as a social movement, among the merits of this work by Mattos is that of recovering the core figure for reasons beyond the abolitionist campaign, “its most important facilitator,” but also “for many essential issues for Brazil,” a contemporary action he undertook with his brother, Antônio (1839–1874), also an engineer. Alonso highlights the gaps that have still not been filled in the studies about André Rebouças, such as him having been such a successful entrepreneur.

Mattos states that the Chão series may help to fill this gap. After Cartas da África, the next works expected to be published are: O engenheiro abolicionista: Diário, 1882-1885 (The abolitionist engineer: Diary, 1882–1885); A abolição incompleta: Diário, 1882-1885 (The incomplete abolition: Diary, 1887–1888); O amigo do

imperador: Registro de correspondência, 1889-1891 (The emperor’s friend: Correspondence records, 1889–1891); and Cartas de Funchal: Registro de correspondência, 1893-1898 (Funchal’s letters: Correspondence records, 1893–1898).

The publication of Rebouças’s writings reveals new themes, such as the author’s “Tolstoism,” discussed in Mattos’s afterword in that issue. The readings of Lev Tolstoi (1863–1947), she explains, are an “important inflection of Rebouças’s liberalism,” and shaped his social thinking. Advocating for a “rural democracy,” Rebouças “remarks on the large financial capital from a rather moral perspective,” similar to that of the Russian author.

The stoic fondness of his convictions, Alonso reminds us, is what prevents Rebouças from accepting the bridges his friends tried to build for him to return to Brazil, which never happened. He died in 1898, not under a palm tree as he had dreamt, but at the toe of a cliff by the ocean, at Funchal, on Madeira Island, where he had lived since 1893.

On the left, a letter written by Rebouças to his friend Rangel da Costa. On the next page, a canvas painting by Rodolfo Bernardelli, from 1897, based on a portrait of the abolitionist’s upper body, from 1885

Republish