While a professor at the São Paulo School of Medicine (EPM), in the mid 1970s, neuroscientist Iván Izquierdo kept a sign on the door of his classroom that read (written by hand): “If in doubt, do not enter.” It was a symbol of the seriousness with which he viewed his profession as a researcher. “Students could knock on the door and enter to discuss issues about their experiments. During work hours, there was no wasted conversation,” recalls neuroscientist Esper Cavalheiro, Izquierdo’s first master’s and PhD student at EPM, which is today the São Paulo University (UNIFESP). The stiffness of work time was broken by coffee breaks and other moments of distraction, when passionately discussing music, literature, and sports.

Izquierdo had arrived there in 1975, at 37 years of age, and was one of the youngest professors at the university. Coming from a brief stint at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), after leading laboratories in Buenos Aires and Córdoba in Argentina, Izquierdo had already built an important international network of collaborators and had risen in his career to the point of being known as one of the top experts in functional memory. “Izquierdo showed Brazilian neuroscience that it was possible to establish international collaborations and to talk as equals with the field’s top researchers in the world,” adds Cavalheiro, today a professor emeritus at UNIFESP. “He taught his students to think. He forged our way of looking at science, of identifying the basic question in the research context and choosing the necessary tools to answer it.”

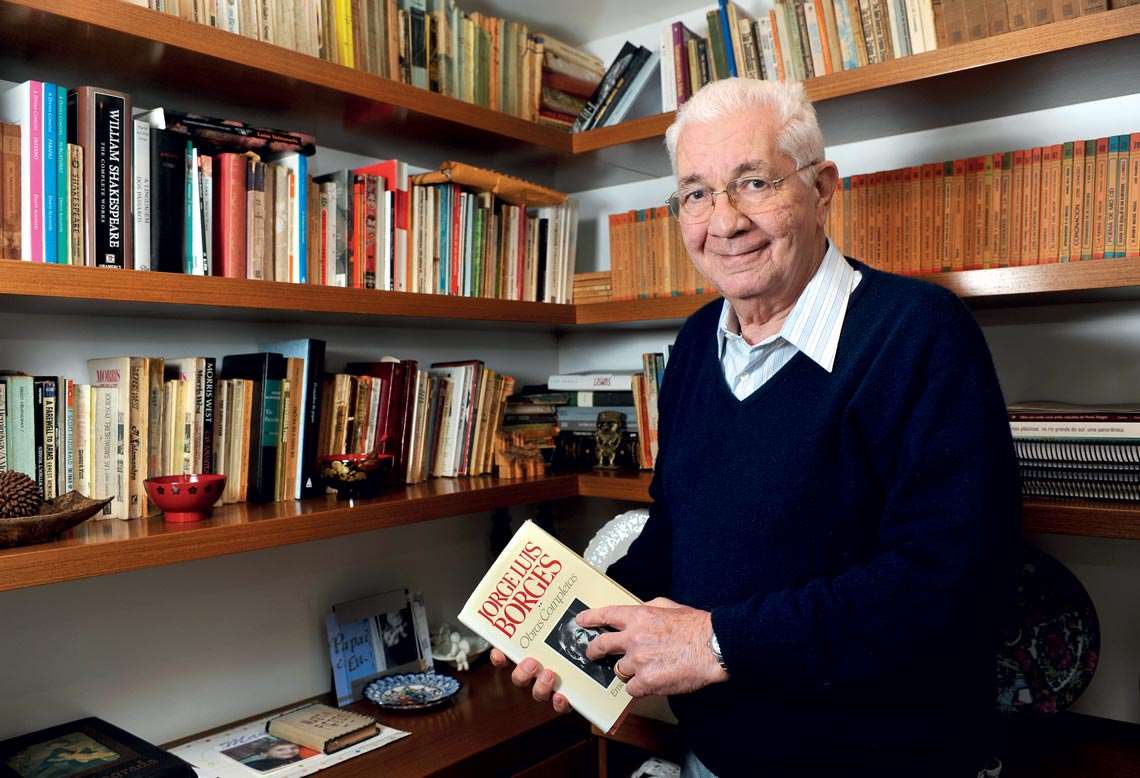

The son of a Croatian mother and Catalan father, Iván Antonio Izquierdo was born in 1937 in Buenos Aires and grew up in a period of cultural upheaval in the capital of Argentina, which at the time was one of the most cosmopolitan cities in South America. With the help of his father, also a scientist, and a Spanish professor, he got to know the works of Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges (1899–1986), who influenced his interest in studying the mechanisms of memory. “He (Borges) asked or answered some of the most serious questions about memory,” wrote Izquierdo in an autobiographical essay published in 2011 in the publication Neuroscience in autobiography, published by Oxford University Press.

Izquierdo entered medical school at the University of Buenos Aires in 1955, months before Bernardo Houssay (1877–1971), who had won the 1947 Nobel prize in Physiology for discovering that the central nervous system regulates the metabolism of glucose, rejoined the institution. At the university, he worked alongside other great names in science, such as Luis Leloir (1906–1987), awarded the 1970 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for identifying lactose metabolic pathways, Eduardo Braun Menéndez (1903–1959), who discovered a system for controlling arterial pressure, and Eduardo De Robertis (1913–1988), who identified key cellular structures for metabolizing medications. At the end of the second year of his undergraduate, Izquierdo presented a research proposal to Houssay, who implemented it the following year. “My project proved to be wrong, but I had bitten the apple for the first time, and I liked the taste,” he would write years later. On the advice of De Robertis, he learned neuropharmacology with his father, Juan Antonio Izquierdo, with whom he did the experimental part of his doctorate.

During the medical program, Izquierdo spent two holiday breaks in Brazil, working in the laboratory of Argentinian neurophysiologist Miguel Covian of São Paulo University in Ribeirão Preto. The country would only enter his life more definitively in 1962. Before leaving to do a post-doctoral internship at the laboratory of Uruguayan neuroscientist José Pedro Segundo at the University of California in Los Angeles, United States, Izquierdo travelled to the region around Porto Alegre and met Ivone de Moraes, who became his wife and mother of their two children: Juan and Carlos Eduardo.

When he finished his two-year internship, he returned to his role as assistant professor at the University of Buenos Aires, which would pay for his time abroad. Two years later, he accepted an invitation to become a tenured professor of pharmacology at the National University of Córdoba, the second oldest in the Americas, where he would remain until 1973, when the political situation in the country became too complex due to the military dictatorship.

Gilson Oliveira / Dissemination PUC-RS

Izquierdo in his laboratory at the Brain Institute which he helped to establish at PUC-RSGilson Oliveira / Dissemination PUC-RSAfter an anonymous threat by phone, Izquierdo decided to leave Argentina. With the help of a Brazilian doctoral student, Mario Tannhauser, he was nominated for a position at UFRGS, which at the time had little history with research. What was intended to be a short break before returning to the United States was extended. In 1975, he took a more interesting position at EPM, where the research environment was more vigorous and attractive. “Izquierdo was my professor during my undergraduate, and to a large extent, he inspired me and educated many generations of neuroscientists,” states Luiz Eugênio Mello, scientific director at FAPESP and also a neuroscientist.

In 1977, Tuiskon Dick, then director of the Center for Biosciences at UFRGS, followed through on a promise made years ago and built a laboratory at the university with the adequate conditions for Izquierdo to return. Dick did not accept Izquierdo’s resignation, and he had granted him an unlimited license. The return to Porto Alegre was permanent. Izquierdo remained at UFRGS until he retired in 2003 and later moved to the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (PUC-RS), where he helped to create and lead the Brain Institute. “I was an Argentinian neuroscientist for the first half of my life and a Brazilian neuroscientist for the second half. Legally, I have two nationalities, and what makes me happy is knowing that I was able to build memory research centers in both countries, as well as strong neuroscience centers,” he wrote in 2011.

He had a prolific career. He published more than 600 scientific articles, cited at least 25,700 times by other groups. His works have helped to uncover the biochemical mechanisms the brain uses to register and retain new information and also to retrieve it, modify it, and even discard it. He also demonstrated that short-term and long-term memories are independent, formed by processes that occur simultaneously. “His work on memory loss has an important potential application in the treatment of post-traumatic stress,” says biochemist Sergio Ferreira, from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), who studies neurodegenerative diseases.

“He was truly a pioneer and a clear voice in a field of study that is sometimes confusing and controversial,” states neuroscientist Mark Bear, researcher with the Picower Institute of Learning and Memory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). “His work has guided some of our key experiments, and we always replicate what he discovered. This is one of the best compliments I can offer.”

Izquierdo advised 50 master’s dissertations and 62 doctoral theses, and he also wrote technical, literary, and scientific education books. He received more than 140 awards and titles, and he was a member of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences and of the National Academy of Sciences in the United States. “Iván was a much-loved individual. He achieved a lot for science in Brazil through what he contributed to science on the world stage,” confirms neuroscientist Roberto Lent of UFRJ and coordinator of the National Translational Institute of Neuroscience, where Izquierdo was involved until recently.

On February 9, Iván Izquierdo passed away at 83 years of age, in his home in Porto Alegre, due to bacterial pneumonia. He had had some signs of Parkinson’s and had recovered some weeks earlier from a serious case of Covid-19. He leaves behind his wife, two children, and four grandchildren. Frustrated by not having been able to dedicate himself to play the guitar, he was delighted when he was awoken some nights by his grandson Felipe playing the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, Ferdinando Sor, or Francisco Tárrega. “It is the closest you can get to heaven while you’re alive,” he had written.

Republish