More than 100 meteorologists and climate scientists from the USA joined together to demonstrate the importance of their research in a 100-hour livestream on YouTube. The event, called the Weather & Climate Livestream, took place between May 28 and June 1. “Whether it’s tomorrow’s temperatures or the sea level in fifty years, Americans need to plan for our futures,” the organizers of the online demonstration said on their official website.

The initiative was launched in response to cuts, layoffs, and other measures taken by Donald Trump’s administration against climate research. In January 2025, Trump began the process of formally withdrawing the US from the United Nations (UN) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), as he did during his previous term (2017–2021). The proposed 2026 budget will reduce funding for the National Science Foundation (NSF), the country’s leading research funding agency, from US$9 billion to US$3.9 billion, while NASA’s funding will be slashed from US$25 billion to US$19 billion. The cuts, which will also affect spending at universities and other research agencies, will impact several areas of science. Climate research is one of the hardest-hit fields, with repercussions not only felt by American citizens.

According to a study by scientists at Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany, published in the journal Environmental Sciences Europe in October 2020, the USA has published more scientific articles on climate change than any other country in the last three decades. It is followed by the UK, China, Australia, and Germany. Of the 15 global institutions that published the most papers on climate science, seven were from the US. However, although still considerable, the proportion of American papers in the climate field fell from almost 60% of the total between 1989 and 1994 to just over 30% between 2015 and 2019.

Even taking this relative decline in academic literature into account, the world is still largely dependent on US-funded Earth observation instruments. The climate data generated by the country is still used by scientists around the globe. The biggest concern regarding the cuts is the potential of losing access to information produced by the satellite network of NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The latter, which lost around 8% of its staff this year (1,300 employees were laid off), plays a crucial role in monitoring the oceans. More than 20 Earth observation satellites are managed by NASA and 18 by the NOAA.

YouTube ReproductionMeteorology and climate researchers from the US take part in a 100-hour livestream on YouTube to protest funding cuts at the end of MayYouTube Reproduction

There are also high-altitude weather balloons, which carry equipment for measuring wind speed, atmospheric pressure, temperature, and humidity, and surface weather stations. This observational infrastructure provides data used to feed mathematical weather forecasting models that focus on the coming days and climate models that look years or decades ahead.

“We have seen a 10% reduction in data from weather balloons over the US as a result of recent decisions made by the Americans,” says French meteorologist Florence Rabier, director-general of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), a leading weather forecaster. According to Rabier, who spoke with Pesquisa FAPESP via the ECMWF press office, information from all over the world is needed for medium-range weather forecasts. “Balloons are the backbone of the global observation system, providing high-precision information to initiate weather forecasts,” adds the director-general of the European center. Thanks to the availability of satellites from different countries, the ECMWF weather forecasting system is relatively resilient to the scarcity of data now coming from the US.

Luiz de Aragão, a researcher from the Brazilian National Institute for Space Research (INPE), believes a crucial component of NASA’s monitoring network when it comes to climate research is the Landsat program, run by the US space agency together with the US Geological Survey (USGS). It is the world’s oldest Earth-imaging program, having been conceived in 1966 and entering operations in 1972. The historical data is invaluable: “A long-term understanding of surface transformation processes is really important for generating accurate climate prediction models. This data must be collected and made available to maintain the historical record,” says Aragão.

The images are stored and made publicly available by the USGS. To date, the service has never been interrupted. However, the Landsat Next mission, tasked with launching a new family of satellites from 2031 onward, was removed from NASA’s website on June 9. The detailed budget proposal for NASA, available online and still awaiting US Congress approval, includes lower funding for Landsat Next. In 2024, the mission received US$56.2 million. For 2026, there is no funding. Instead, the document states that the funds needed for Landsat have been allocated to the Sustainable Land Imaging division, which has a budget of US$70 million for next year. There is no information, however, about which other programs were included under the same heading and how the mission will be remodeled. The document also outlines funding cuts for other climate-related Earth observation projects in 2026. For the 2024 fiscal year, the cuts in this area of NASA exceed US$270 million.

NASAIllustration of the NASA and USGS Earth observation satellite Landsat 9NASA

Physicist Alexandre Costa of the State University of Ceará (UECE) believes that if this level of dismantling had occurred 20 or 30 years ago, the consequences would have been worse. “We are no longer as dependent on the US for data generation as we once were,” points out the atmospheric science expert. “In the field of satellite monitoring and climate modeling, the European community, Japan, and China are strong competitors. But it must be said that US agencies are still the main providers of databases.”

The NOAA recently had to discontinue its Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters database, which has tracked the cost of climate disasters in the country since 1980. A platform containing data on ice and snow cover, particularly in the Arctic and Antarctic, was also suspended. “Everyone knows that climate change is expensive. There is an attempt to cover up the facts because the data is inconvenient,” economist Rachel Cleetus of the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), a nongovernmental organization that advocates for issues such as climate and energy, said in an interview with Pesqusia FAPESP.

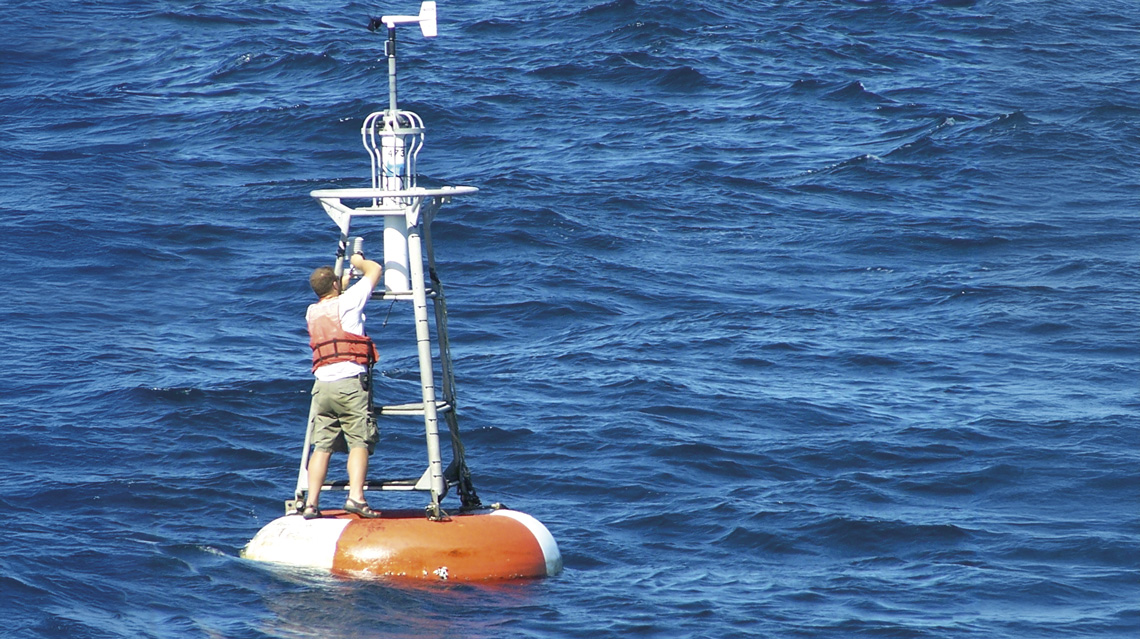

In addition to the mass layoffs at NOAA, the proposed 2026 budget would eliminate an entire research area at the agency. The Oceanic and Atmospheric Research division, responsible for more than a dozen ocean monitoring programs, received US$638 million in 2024 and US$608 million this year. One project at risk of being shut down if the budget is approved is the Global Tropical Moored Buoy Array, a set of buoys anchored offshore used to analyze changes in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans, as well as ocean-atmosphere interactions.

“All of our scientific understanding about El Niño and La Niña patterns came from these buoys in the Pacific, part of the TAO array, which was created in 1985 to study the phenomena,” says Regina Rodrigues, an oceanographer from the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC) who did a postdoctoral fellowship at NOAA. The PIRATA Project, the Atlantic branch of the Global Tropical Moored Buoy Array, has been operating for 30 years and involves partner institutes from France and Brazil, such as INPE and the Brazilian Navy. “The cuts could impact production of the buoys, which is handled by the NOAA. This could lead to a reduction in the number of active buoys, creating gaps in the data at locations where they are missing,” comments Rodrigues.

The Argo program, part of the same research division at the NOAA, is another at risk in 2026. Created in 1999, it deploys 4,000 robots that dive to a depth of 2,000 meters for two weeks at a time to measure water temperature, ocean currents, and salinity. There are thirty countries participating in the initiative. “The US contributes half of the robots to the system, which has been essential to our understanding of where excess heat from climate change is going,” American oceanographer Rick Spinrad, director of the NOAA between 2021 and 2025, said in an interview with Pesquisa FAPESP. “Unless a consortium of nations can play the same role, we might lose the data and the equipment.”

The story above was published with the title “Stormy outlook in the USA” in issue 353 of July/2025.

Republish