In October 1951, American physicist David Joseph Bohm (1917–1992) left the United States for Brazil to take up a position as professor and researcher in the then Department of Physics at the School of Philosophy, Sciences, and Letters at the University of São Paulo—later to become the USP Institute of Physics (IF-USP). But he did not come happily. His departure was, in effect, an escape.

“The story of David Bohm is the story of McCarthyism and the persecution of Robert Oppenheimer’s [1904–1967] former students,” summarizes physicist and historian Olival Freire Junior, from the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), author of the biography David Bohm: A Life Dedicated to Understanding the Quantum World (Springer, 2019).

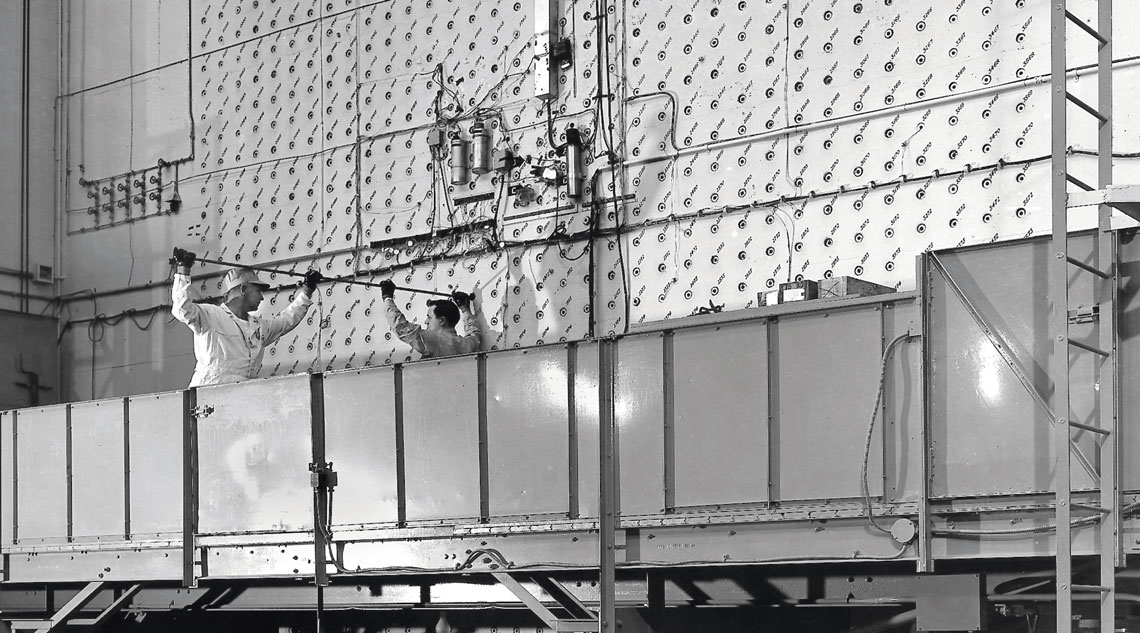

Oppenheimer had wanted to hire Bohm for the Manhattan Project, which he directed, but Bohm was vetoed because of his political activities at the University of California, Berkeley. The Manhattan Project was the secret US program to build the first atomic bombs. Bohm’s hypotheses about the collision of atomic particles proved useful in the development of the nuclear weapons that destroyed the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945.

Bohm was already well known in the field of quantum mechanics, but he became a target of the anticommunist campaign led by Senator Joseph McCarthy (1908–1957). In May 1949, summoned to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, which was investigating allegations of espionage, he refused to answer questions about his political beliefs.

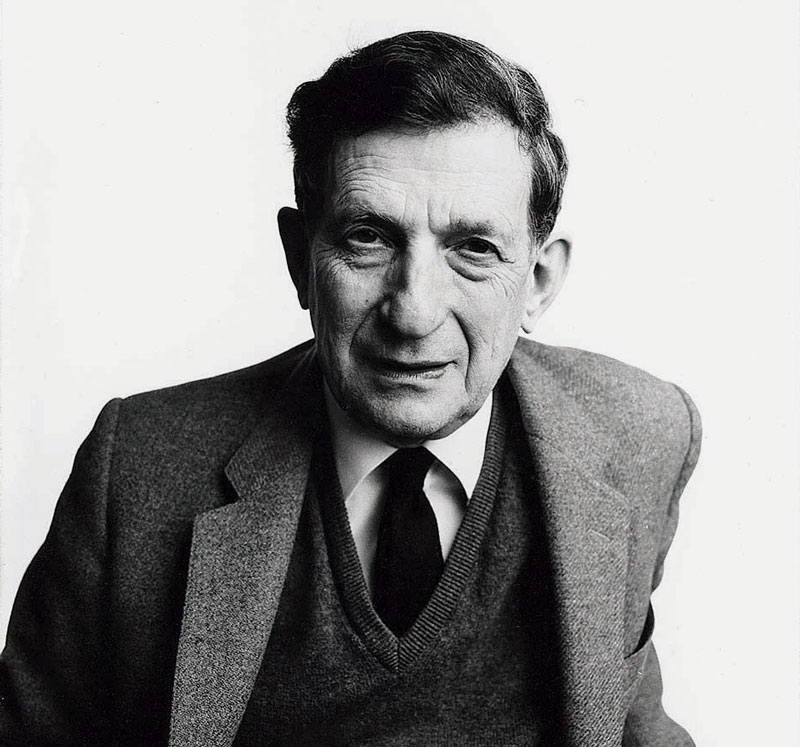

Mark Edwards / American Institute of Physics Portrait of Bohm in the late 1980s, in LondonMark Edwards / American Institute of Physics

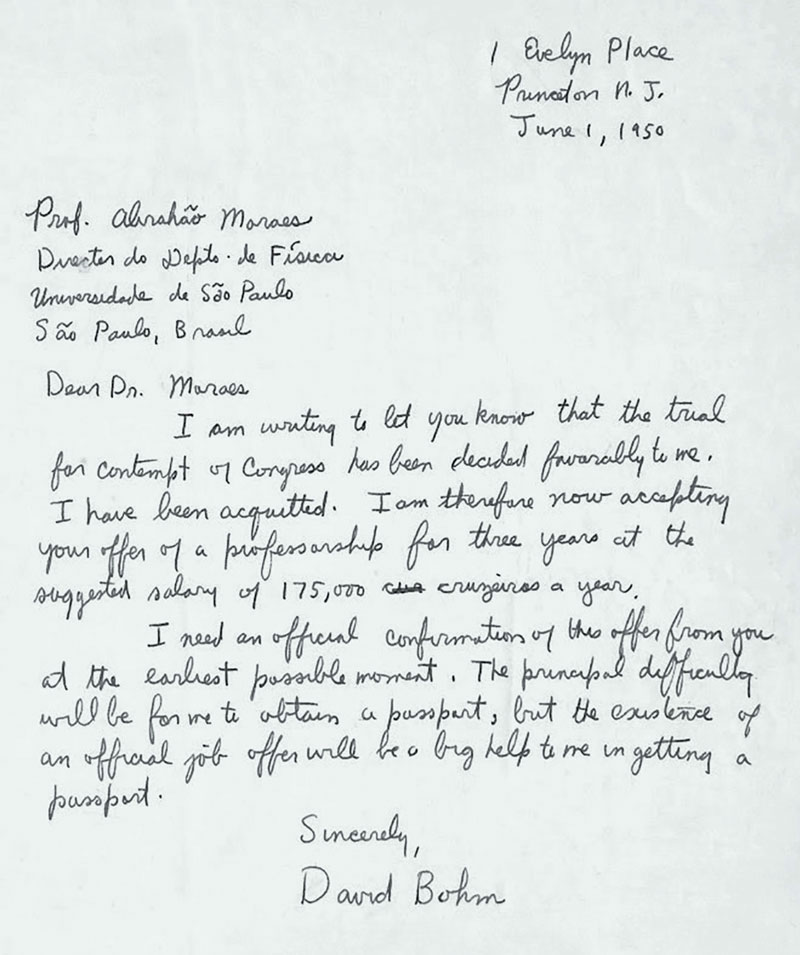

A member of the Communist Party since 1942, Bohm invoked the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution and remained silent. Although acquitted, he lost his position at Princeton University, where he had been a colleague of Albert Einstein (1879–1955).

The political climate in the United States was increasingly threatening, culminating in the 1953 execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg (1918–1953, 1915–1953), accused of passing information about the atomic bomb to the Soviet Union. Given these circumstances, Bohm’s friends mobilized to help him leave the country. He was regarded as one of the most brilliant physicists of his generation.

“Brazilian graduate students at Princeton—Jayme Tiomno [1920–2011], José Leite Lopes [1918–2006], and Walter Schützer [1922–1963]—invited him to go to São Paulo after Princeton chose not to renew his contract,” says Freire Jr. Einstein himself wrote a letter of recommendation to the director of USP’s Physics Department, Abrahão de Moraes (1917–1970). In May 1952, Einstein also wrote a letter of support for his young colleague addressed to President Getúlio Vargas (1882–1954), to be delivered in case of any political trouble—though it ultimately was not needed.

The trip to Brazil was tense from the beginning, according to British physicist Francis David Peat (1938–2017) in his book Infinite Potential: The Life and Times of David Bohm (Addison-Wesley, 1996). Bohm feared he would be arrested when the plane, already preparing for takeoff, was ordered back to the terminal because of an irregularity in one of the passengers’ passports. To his relief, the problem was with someone else.

In São Paulo, no one was waiting for him at the airport. He had sent a telegram to USP with his arrival time but had forgotten to address it to the Physics Department. Not knowing a word of Portuguese, he set out in search of a hotel. The next day, he managed to find Tiomno, who arranged for him to stay in a boarding house on Avenida Angélica. This marked the beginning of a period that would leave a lasting mark on both the life of the exiled scientist and the history of Brazilian science.

Jayme Tiomno archivePrinceton, March 1949: kneeling, Hervásio de Carvalho, José Leite Lopes, and Jayme Tiomno; standing, César Lattes, Hideki Yukawa, and Walter SchützerJayme Tiomno archive

Responsible for translating the correspondence between Bohm and Einstein, Freire Jr. recounts that upon arriving in Brazil, the young exile wrote to his friend in an optimistic tone: “The university is quite disorganized, but that won’t hinder the study of theoretical physics. There are several good students here, with whom it will be good to work.” Some of these students would go on to become leading figures in Brazilian physics, such as the couple Ernst and Amélia Hamburger (1933–2018, 1932–2011), Moysés Nussenzveig (1922–2022), Newton Bernardes (1931–2007), and Ewa Cybulska (1929–2021). Bohm taught theoretical physics in Portuguese in 1953 and quantum mechanics in 1954.

His mood changed over time. In letters to friends, he complained that Brazil was “an extremely backward and primitive country,” said the food gave him digestive problems, lamented the noise in the streets, and wrote that he had no one to talk to. He also mentioned conflicts between alleged Nazis in USP’s Physics Department. In fact, according to Freire Jr., these were merely internal disputes over hiring, sometimes involving German physicists who were mistakenly associated with Nazism.

In an interview given in March 1983 to Alberto Luiz da Rocha Barros (1930–1999) from IF-USP, and published in April 1990 in Revista de Estudos Avançados, Bohm offered a more generous assessment: “Many of my ideas developed considerably during my stay in Brazil—and many new ideas also emerged.” How can this apparent contradiction be understood? According to Freire Jr., the complaints reflect the depression brought on by exile, which Bohm sought to treat with electroconvulsive therapy, since medication did not seem to help.

The confiscation of his passport by a US consulate official less than a month after his arrival in Brazil left him, in his own words, “depressed and restless,” fearful of deportation, as he wrote in a letter to a friend. Without a passport, he could not attend international conferences to defend a new and challenging theory he had developed at Princeton and, once in Brazil, published in two articles in Physical Review in January 1952: a deterministic description of quantum phenomena.

Archives of the National Academy of Sciences Bohm (last standing, right) with Oppenheimer (first seated, left) at the Shelter Island Conference in the United States in 1947, dedicated to the fundamentals of quantum mechanicsArchives of the National Academy of Sciences

Up to that point, quantum physics, which describes phenomena on a subatomic scale, was grounded in the so-called Copenhagen interpretation, which Bohm had explained in accessible terms in his book Quantum Theory (Prentice Hall, 1951), based on a course he had previously taught at Princeton. According to this view, elementary particles of matter, such as electrons, can behave either as particles (with a defined location) or as waves (spread across a region). Because of their wave-like nature, it was not possible to define both the position and momentum of a particle at the same time; the description of subatomic phenomena was necessarily probabilistic, indicating only the likelihood of particles being in one place or another. Bohm, however, rejected this duality. For him, particles always had well-defined positions, guided by a “pilot wave,” or quantum field.

The silence of his colleagues

In a 1983 interview, Bohm explained that the quantum field “acted on the particle through a quantum potential that had strange properties, one of which was that it did not always decrease with distance; it could be very strong even at great distances. I called this nonlocality.” His reinterpretation of quantum mechanics was not well received by colleagues, some of whom responded with awkward silence.

Physicist Amir Caldeira, from the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), acknowledges that it is not easy for experts in the field to immediately accept a new quantum theory. “In terms of predicting experimental results, quantum mechanics is the most accurate theory we know,” he says. For him, Bohm was searching for something else: “a description of physical reality, which is not possible within quantum mechanics.”

Historical Collection of the USP Physics Institute Letter from Bohm to Abrahão de Moraes in 1950 confirming his interest in the physics chair at USPHistorical Collection of the USP Physics Institute

To this day, Bohm’s realistic interpretation exists alongside the traditional one, but it has not been strong enough to replace it. Even Bohm’s Brazilian students did not adopt it. The incompatibility between the concept of atomic nonlocality and realistic interpretations was experimentally confirmed by Frenchman Alain Aspect, American John Clauser, and Austrian Anton Zeilinger, who shared the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physics, based on a theorem developed in 1964 by Northern Irish physicist John Stuart Bell (1928–1990).

In a 2001 interview with the digital magazine ComCiência, Amélia Hamburger commented that Bohm’s greatest contribution was perhaps to bring São Paulo physicists “a mindset of freedom and imagination.” Freire Jr. agrees: “His great achievement was daring to question what was already considered established, even though the new deterministic view of the quantum world was not accepted by the entire scientific community.” In his view, the American physicist put USP and Brazil on the map of debates in quantum mechanics.

While in Brazil, Bohm maintained contact with colleagues abroad and welcomed international visitors. Physicists such as Ralph Schiller (1926–2016) from the United States, Mario Bunge (1919–2020) from Argentina, Jean-Pierre Vigier (1920–2004) from France, and Léon Rosenfeld (1904–1974) from Belgium visited thanks to research grants from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), created in 1951—the same year Bohm arrived in Brazil. The agency was established to support scientific research and development in the country.

It was not only Bohm’s arrival that energized Brazilian physics in the early 1950s, notes physicist and philosopher Osvaldo Pessoa Jr., from the School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences (FFLCH) at USP, who organized a symposium on Bohm at IF-USP in 1998. “César Lattes [1924–2005], when he returned from Europe in 1948, created a movement for science in Rio de Janeiro,” he says.

Lattes was one of the founders of the Brazilian Center for Physics Research in Rio de Janeiro in 1949 (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue no. 340), the year he received a visit from American physicist Richard Feynman (1918–1988), who would later win the 1965 Nobel Prize in Physics. “Bohm’s arrival came at a very opportune moment, during the institutional consolidation of research in Brazil,” Freire Jr. points out.

Ricardo Gumbleton Daunt Identification InstituteDocument issued by the Brazilian Consulate in New York in 1951Ricardo Gumbleton Daunt Identification Institute

Physicist Iberê Caldas, from IF-USP, highlights Bohm’s contribution to research in plasma physics—a gaseous mixture of atomic particles carrying positive or negative electric charges. According to him, Bohm’s work in this field, “still well known today,” shaped the scientific and academic career of Walter Schützer in Brazil. “Schützer was one of Bohm’s closest collaborators in the Physics Department,” he notes.

Bohm’s dialogues with Mário Schenberg (1914–1990), director of the Physics Department from 1953 to 1961 (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue no. 307), were also fruitful. Both Jewish communists, they disagreed on how to interpret quantum phenomena and the nature of the real world. Schenberg recommended that his colleague read the works of German philosopher Georg Hegel (1770–1831), considered indispensable for every communist.

At the end of 1954, Bohm obtained Brazilian citizenship and was finally able to leave the country. In January 1955, he took up a teaching post at the Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, and two years later moved again, to positions at the University of Bristol and later the University of London. At that time, he immersed himself in the study of philosophers and mystics, searching for a broader understanding of reality. These readings brought him into dialogue with the Indian philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895–1986), with whom he discussed the concept of totality and the interconnectedness of existence.

Although Bohm never returned to Brazil, in July 2025 the Institute of Advanced Studies at USP held a symposium with 24 speakers to reflect on his time in the country and to commemorate the centenary of Schrödinger’s equation, a milestone in quantum theory. Formulated in late 1925 by Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger (1887–1961), the equation describes how the quantum state of molecular or atomic systems evolves over time.

American physicist Bill Poirier, from the University of Vermont and chair of the organizing committee, recalls being captivated by Bohm’s Brazilian story when he gave a seminar at USP in 2018—fittingly, in a room named after Jayme Tiomno. “I was fascinated by what I learned,” he says. “I was also surprised to discover that few in the room knew anything about this story.”

The story above was published with the title “Lessons in freedom” in issue 355 of September/2025.

Scientific articles

BOHM, D. O aparente e o oculto: Entrevista com David Bohm. Revista de Estudos Avançados. Vol. 4, no. 8. Apr. 1990.

FREIRE JR. O. et al. David Bohm, sua estada no Brasil e a teoria quântica. Estudos Avançados. Vol. 8, no. 20. Jan. 1994.

HAMBURGER, A. Física quântica no Brasil. ComCiência. May 2001.

Books

FREIRE JR., O. David Bohm: A life dedicated to understanding the quantum world. New York: Springer, 2019.

PEAT, F. D. Infinite potential: The life and times of David Bohm. Reading: Addison-Wesley Pub Wesley Publishing Company, 1996.