The formation of coalitions, usually majority coalitions, has been the predominant way of governing in Brazil. Although elected to exercise an independent mandate, with the ability to freely appoint his or her ministers, the strength of coalition presidentialism is not based in the office of the president, but in the powers that give the occupant of the Planalto Palace the capability to influence the process of defining public policy. “The institutional basis of coalition presidentialism from 1988 onwards is the power to define the legislative agenda, which is conferred by the constitution, complemented by the centralization of decision-making within the Congress.” This conclusion comes from political scientists Argelina Cheibub Figueiredo and Fernando Limongi, in a discussion recently published in Dados – Revista de Ciências Sociais (Data: Journal of social sciences). According to their research, in Brazil rulers cannot escape what they classify as an imperative: “If they want to pass laws and change existing policies, presidents will be forced to seek support from the parties in the legislature.” Since the early 1990s, Figueiredo and Limongi have been taking turns coordinating a team of researchers investigating relationships between the executive and legislative branches of federal government. In December 1999, the initial results of their research were the subject of the magazine’s cover story.

The idea of investigating the relationship between the two powers came from Argentine political scientist Guillermo O’Donnell (1936–2011), based on interest expressed by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation in funding scientific research, in Brazil, on the country’s National Congress. “When I joined CEBRAP [the Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning] in 1990, O’Donnell was already there, and he asked me to prepare a preliminary project. In Brazil there had been little research regarding Congress, seen then as a kind of realm of the individual parliamentarian and treated as a single actor. All previous studies had dealt with parliamentary behavior, and thought about the subject from the perspective of electoral legislation,” recalls Figueiredo, currently a professor at the Institute of Social and Political Studies of the State University of Rio de Janeiro (IESP-UERJ).

Named by O’Donnell, the study “Terra incógnita – Funcionamento e estrutura do Congresso Nacional” (Terra Incognita: The operation and structure of the National Congress) began in 1991 without his further participation, receiving US$200,000 from the Mellon Foundation. Emphasis was given to studying the activities of the Câmara dos Deputados, Brazil’s House of Representatives. “We decided to collect all data on the processing of legislation from 1988 onwards. Our guideline was to not use what the Representatives said as a source, but rather what they did,” says Figueiredo. For this reason, there were very few interviews. Only a few House leaders who played relevant roles in drafting internal bylaws were questioned.

“The president remains the country’s principal legislator, with control of the budget and bureaucracy, and with the ability to issue Provisional Measures,” Limongi explains.

At that time, researching at the National Congress was no simple task. In the beginning, the House documentation department employees would do searches as requested by the study team, send the printed material to São Paulo, and, at CEBRAP, the researchers then systematized the information into spreadsheets. With the arrival in 1993 of Limongi, a professor at the School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences of the University of São Paulo (FFLCH-USP), roll call voting became part of the scope of the investigation, making it necessary to photocopy thousands of pages of the daily Congressional digest. These were used to map the activities of each of the Representatives. The discovery of previously ignored topics regarding the legislative process, such as vote abstentions, and guidance from the party leader, for example, brought about extra trips to Brasília to collect data. “With this research, we fell into the center of the Brazilian institutional debate that followed post-military democratization, i.e., whether presidentialism worked or not,” says Limongi, currently a professor at the São Paulo School of Economics of the Getulio Vargas Foundation (FGV-EESP). Within academia, then current opinion was that the political system would not work.

Among scholars on the subject, such as American political scientists Barry Ames and Scott Mainwaring, and Spanish sociologist Juan Linz (1926–2013), the viewpoint established in 1964 remained: that the highly conservative Legislature in Brazil would be an obstacle to action by the Executive. The problem would be governability. “The idea of Congress as a blackmailer of the Executive was predominant,” says Figueiredo. “Linz, for example, believed that since presidents could choose their ministers, they wouldn’t have incentives to make coalitions.” FFLCH-USP political scientist Regis Stephan de Castro Andrade (1938–2002) was one of the first to shift the focus of the investigations. By analyzing the power of committees, he began to bring attention to the innovations brought about by the then recently-approved Constitution. The research coordinated by Figueiredo and Limongi would ultimately show that the existing relationship between the Executive and the Legislature derives from the constitutional text.

The cover story of issue no. 49 of Pesquisa FAPESP reported on the study of patterns of interaction between the executive and legislative branches of government

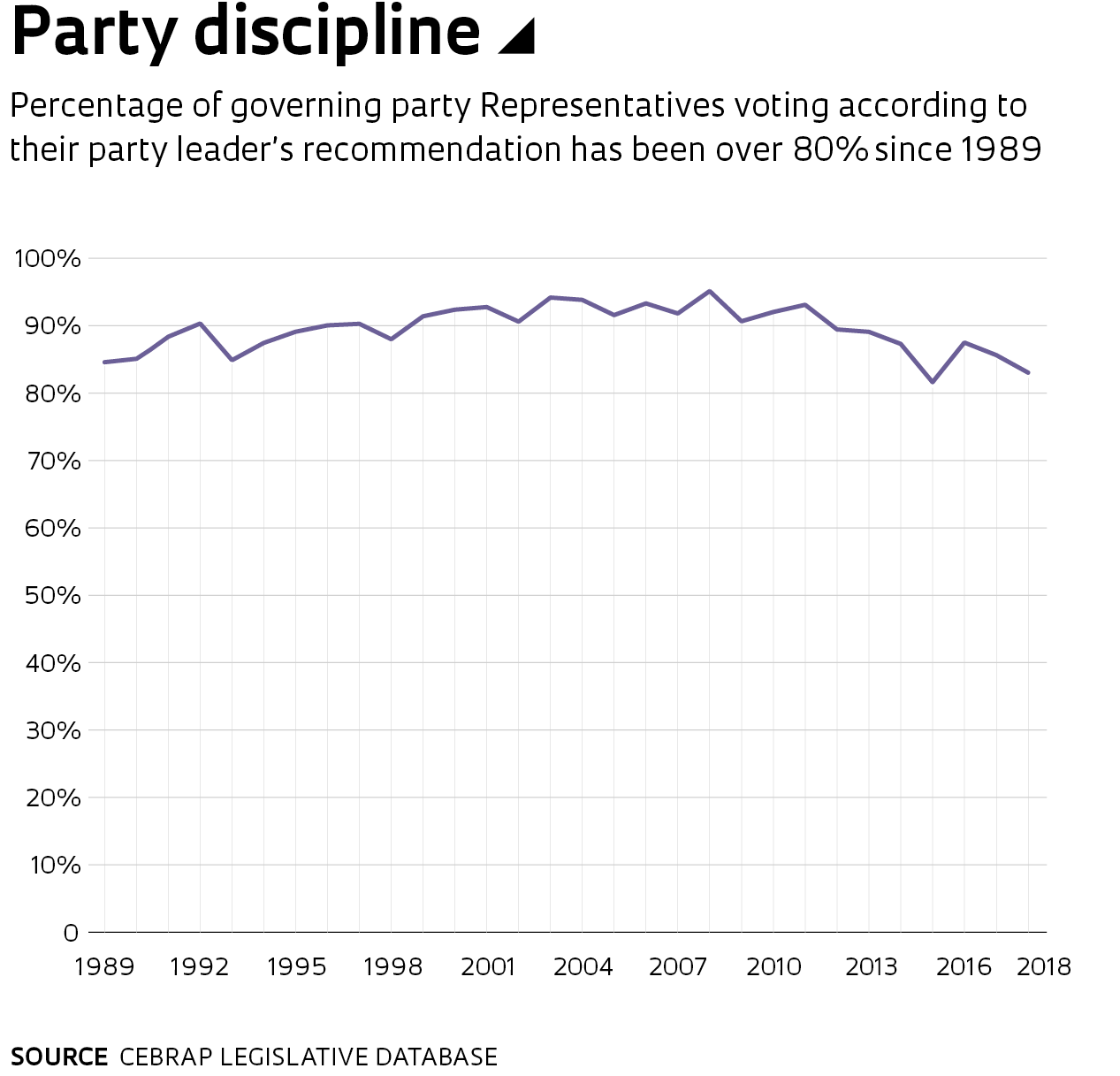

Party discipline

Without a stated hypothesis, the initial concern of the scholars was to understand the functioning of the Brazilian political system and what role the Legislature played. They decided to follow the procedural paths of governmental proposals. “If the executive branch is supposedly unable to get its measures approved because the Legislature is uncooperative and blocks them, let’s look at the Executive’s bills to see what actually happens,” Limongi proposed. The general perception was that individualism prevailed in Congress and that there was a lack of discipline between political parties.

“I didn’t have any expectation it would be otherwise, until our first statistics indicated that party discipline did exist. It was surprising,” he reports. Since 1989, the percentage of members of the governing party who voted according to their party leader’s recommendation has been above 80%. During the research, they also came to the realization that House and Senate bylaws favor the political parties. “At the institutional level, parties are privileged political actors,” he adds (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue no. 114).

The comparison between the constitutional texts showed that all the reforms made by the prior military regime to reinforce the power of the Executive were maintained in the current Constitution. For example, the Provisional Measure (a mechanism similar to an Executive Order in the United States), is an adaptation of the former military Decree Law to the democratic system. Unlike the 1946 Constitution, according to Figueiredo and Limongi, the political model implemented in Brazil from 1988 onwards combines “rules for diffusing power in the system of representation, and for the concentration of power in the decision-making system of government.” “The President remains the country’s principal legislator, with control of the budget and bureaucracy, and with the ability to issue Provisional Measures,” summarizes Limongi. In his view, it is a tendency observed in the democratic constitutions approved since World War II. “Such a feature, with a ‘rationalized parliament’ [a legislative branch weakened to give more power to the Executive] is not at odds with modern constitutional theory. If I were to write a constitutional text, I would write it that way,” he says.

The institutional foundations of coalition presidentialism lie in the legislative power of the president, who has mechanisms to control the congressional agenda, says Figueiredo.

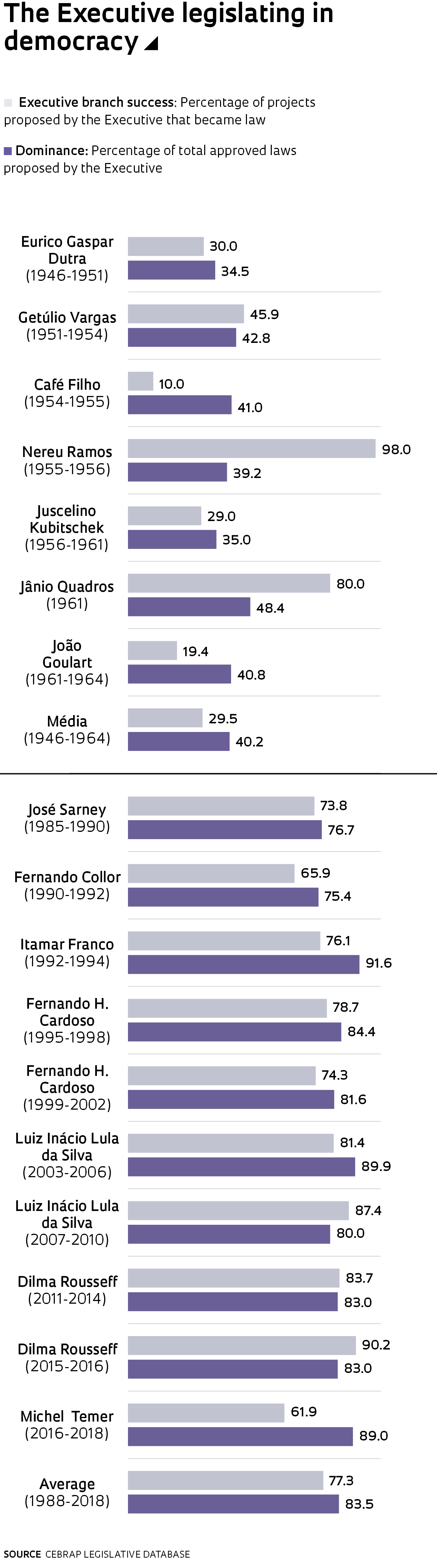

This reflects, for example, the pattern of success and dominance the Executive has in passing national legislation, which is very similar to that observed in parliamentary governments. The executive branch’s pattern of success refers to the percentage of the President’s proposals that become law. Dominance, in turn, refers to the percentage of the total number of approved laws that were put forward by the President. Since Brazil’s return to democracy, the average has been 77.3% and 83.5%, respectively. “During the course of our research, we identified that the institutional foundations of coalition presidentialism lie in the legislative power of the president, who has constitutional mechanisms to control the congressional agenda,” Figueiredo explains.