Robust evidence is beginning to emerge of a phenomenon feared by oceanographers and climate scientists: deep ocean water warming. From 2009 to 2019, temperatures in the Atlantic Ocean’s abyssal zone, located more than 4,000 meters (m) below the surface, increased by 0.02 to 0.04 degrees Celsius (°C). The small but extremely important increase was recorded by an international group of researchers and presented in an article published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters in September 2020. According to the experts, one of the most likely causes of rising temperatures at sea, where 97% of all the water on Earth is stored, is climate change resulting from the emission of greenhouse gases by human activity, which have already heated up the atmosphere by about 1°C since 1900. “We now have consistent evidence that the rising average temperature of the atmosphere is being reflected in the depths of the oceans,” says Brazilian oceanographer Edmo Campos, from the University of São Paulo (USP), one of the authors of the study, carried out in partnership with the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the University of Buenos Aires in Argentina. “Slowly, they are warming up,” says Campos.

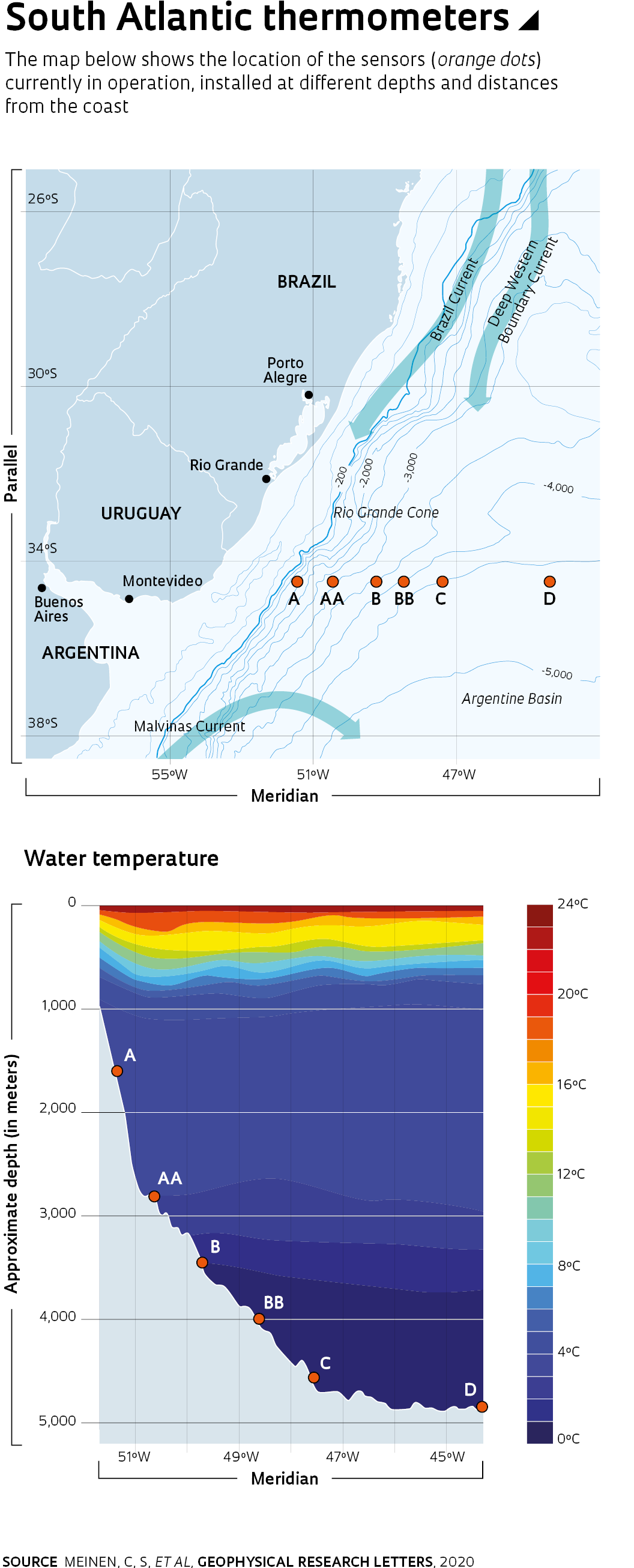

The researchers analyzed data from what is probably the longest series of continuous measurements ever taken in abyssal ocean regions south of the equator. For at least a decade, sensors located at four points at the bottom of the Atlantic recorded the water temperature on an hourly basis. Installed in 2009 on an expedition aboard the the Brazilian Navy’s hydroceanographic vessel Cruzeiro do Sul, the depths of the devices range from 1,360 m to 4,757 m. Along with others installed later, some with funding from FAPESP, the devices are situated 1 m from the ocean floor along the 34.5° parallel south, a circle of latitude around the globe that passes close to the municipality of Chuí in Rio Grande do Sul and Cape Town, South Africa.

Oceanographers collect data from this fundamental parallel to study how changes in atmospheric temperature affect the Atlantic Ocean’s abyssal zone—temperature alterations at these great depths can cause drastic changes to the planet’s climate. Icy waters from Antarctica, the temperatures of which are measured in tenths of a Celsius, pass through this latitude at depths greater than 4,000 m, flowing to the north and spreading across the ocean floor. These Antarctic waters function as one of the rare direct connections between the atmosphere and the deepest areas of the world’s oceans. In tropical regions of the planet, the air is hotter than the water and transfers heat to the surface layers of the sea (up to a thousand meters deep). Near the poles, however, the situation is reversed: the air is much colder than the water and extracts heat from the sea surface. This phenomenon occurs, for example, in a region of the Southern Ocean called the Weddell Sea, near several Antarctic research stations, including Brazil’s.

The surface waters of the Weddell Sea lose heat to the atmosphere, become denser, then sink. As they descend, they move under a middle layer of warmer water, heading towards the northern hemisphere at a speed of a few hundred kilometers a year. Since there is almost no thermal variation at great depths, the temperature measured near the ocean floor at the 34.5° parallel south is more or less the same as the water that descended in the Antarctic. The problem is that due to rising average air temperatures, polar ice is melting and the descending water seems to be slightly warmer.

Alberto Piola / University of Buenos Aires

Researchers on the vessel Puerto Deseado prepare to anchor a rig to the ocean floor in 2016Alberto Piola / University of Buenos AiresA few hundredths of a Celsius difference in water temperature in the abyssal zone may seem insignificant, but it is not. Water is one of the natural substances that requires a greater amount of energy to heat up. “The energy needed to increase the water at the bottom of the ocean by a few hundredths of a degree would cause an increase in the order of degrees in the atmosphere,” says the oceanographer. And the deep Atlantic stores an enormous volume of water. “These small changes can have significant effects on the global circulation of the ocean, and consequently on the way heat is absorbed and redistributed by different regions of the planet,” explains Campos, who is also a researcher at the American University of Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates and coauthored chapter 3 of the Fifth Assessment Report of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), presented in 2014.

Scientists have long suspected that the oceans are warming up. Measurements taken over the last four decades by instruments on ships capable of recording the temperatures of the entire water column, or more recently, surface temperature readings taken by satellites or buoys, already indicated an upward trend. These data, however, have been the subject of debate because measurements were not always taken at the same locations or the intervals were too long. “The infrequent measurements led to doubts,” reports Argentine oceanographer Alberto Piola, from the University of Buenos Aires and the Argentine Naval Hydrographic Service, one of the study’s coauthors. “The new data allow us to confirm that the warming trend seen over these 10 years is robust and similar to that observed in previous surveys, suggesting that it is a response to global warming,” he says.

According to meteorologist Pedro Leite da Silva Dias, director of USP’s Institute of Astronomy, Geophysics, and Atmospheric Sciences (IAG), who did not take part in the study, the hourly measurements taken on the ocean floor eliminate the possibility of the temperature change being due to inadequate sampling, which could distort the data. “The increase observed in this study is compatible with what we expect as a result of global warming,” says Dias, who contributed to the IPCC’s fourth assessment report, issued in 2007. “If natural temperature cycles were the cause, the increase would be smaller,” he explains.