Criticized as alarmist and inaccurate by the federal government and threatened with replacement by a private service, the system developed by the Brazilian National Institute for Space Research (INPE) to monitor deforestation in the Amazon has earned academic prestige and international recognition. About 1,200 scientific articles published in indexed journals have used data provided by its Amazon Monitoring Program for Legal Deforestation (PRODES), which functions alongside the Real-Time Deforestation Detection System (DETER). The former has been assessing annual deforestation rates based on satellite imagery since 1988; the latter has been operating since 2004, issuing daily alerts about areas losing forest cover. “There have also been hundreds of theses and dissertations written based on data from these programs which have been used in studies to expand our knowledge of remote sensing,” says statistician Thelma Krug, an INPE researcher who helped create PRODES and has been vice president of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) since 2015.

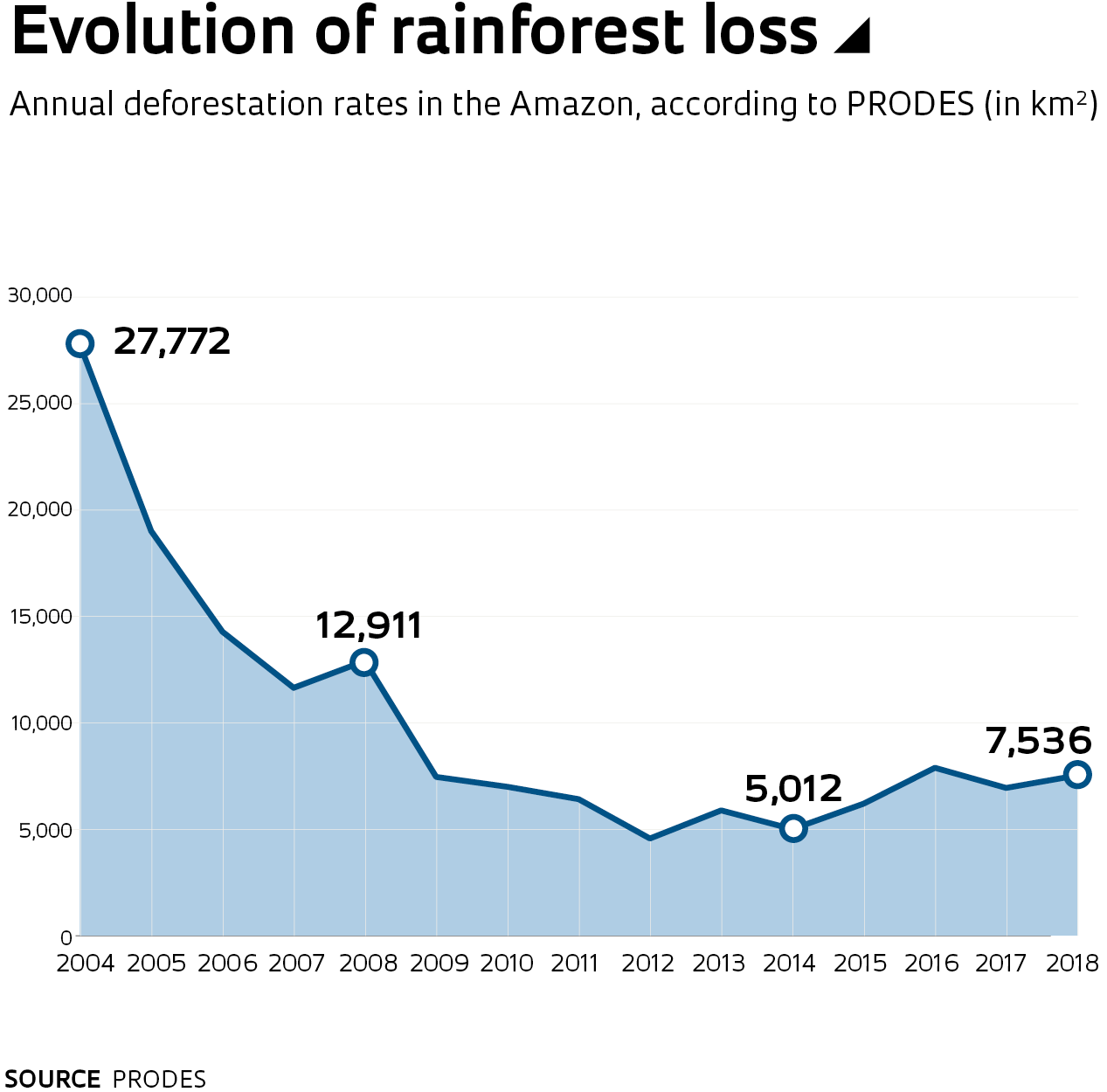

PRODES data, released once a year, is used to certify agribusiness production chains and monitor compliance with pacts agreed between farmers and environmental agencies, such as the Amazon Soy Moratorium. It is also used as a point of reference by countries that donate to the Amazon Fund (Norway and Germany), which is currently suspended but has to date raised R$1.1 billion to help prevent and combat deforestation and to catalog greenhouse gas emissions, giving an overview of Brazil’s performance in international climate change targets. Data from the DETER program, meanwhile, has had a significant impact on public policy in the Amazon: the alerts sent to the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) have been used to guide their inspectors and are at the root of the fall in deforestation rates seen since the beginning of this century. In 2004, 27,700 square kilometers (km²) of rainforest were cleared, falling to around 4,500 km² in 2012—the annual average over the last three years has risen to about 7,000 km².

The idea of creating a national system to monitor the Amazon first arose in the late 1980s, when international pressure to preserve the rainforest forced the Brazilian government to react and make a firm commitment. Curiously, in direct contrast to the current situation, INPE has historically faced criticism for producing data considered conservative, generally falling short of calculations made by other institutions. Its choice of methodology is one reason for the discrepancy. The definition of deforestation adopted by PRODES in 1988 is the clearcutting of an area of at least 6.25 hectares. Clearcutting means removing all existing vegetation in an area. “Back then, we had to interpret satellite photos on paper, which were lower resolution than the images we have access to today. The minimum mapping unit, equivalent to 250 square meters, was created because it enabled a reliable analysis,” explains engineer and geoprocessing expert Gilberto Câmara, one of the founders of DETER, who was director of INPE from 2006 to 2013 and now heads the Group on Earth Observations (GEO), an organization based in Geneva that helps countries comply with international agreements by sharing satellite data and other technologies.

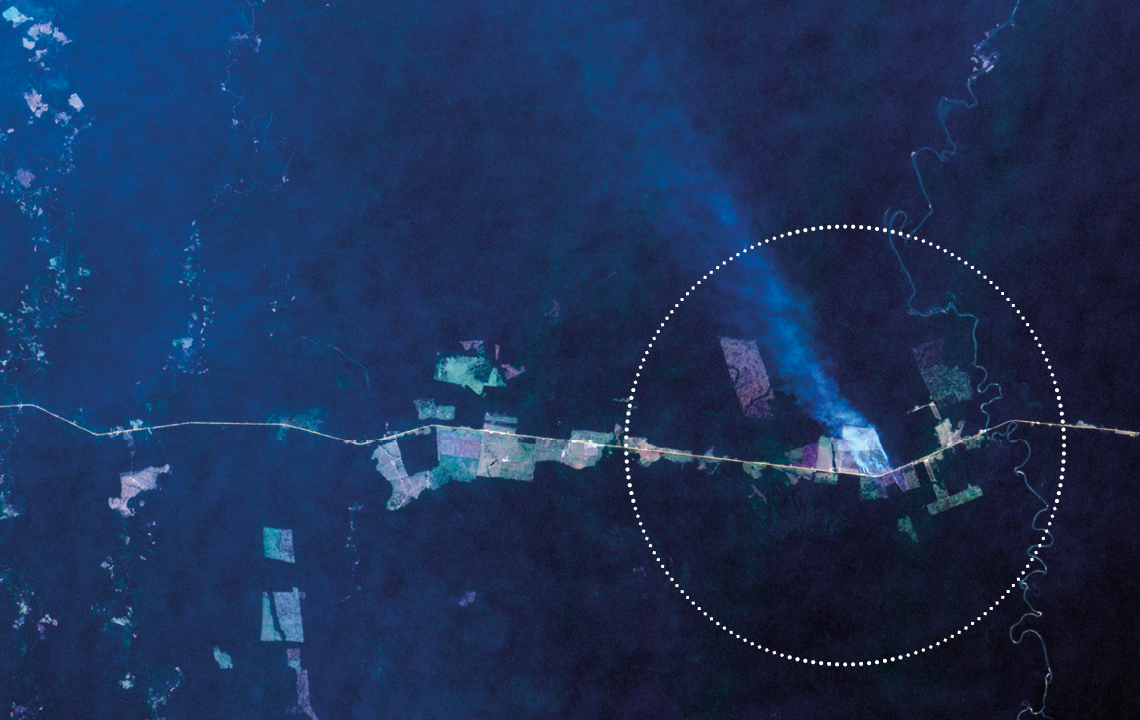

An alert system was created in 2004 to tackle increasing levels of deforestation

The objective of PRODES, explains Câmara, was to prevent areas from being wrongly identified as deforested, known as false positives, even if it increased the risk of ongoing clearing processes going undetected. “The theory was that when areas smaller than 6.25 hectares were cleared, they would progress and be identified the following year.” With the quality of images and technology available today, it is possible to make more accurate detections on a smaller scale, but INPE has chosen to maintain the methodology to enable comparison with the historical data. “This way, it’s possible to delimit the area of primary Amazon rainforest, which is still maintained today and has never been altered,” says Krug.

Government criticism is focused on DETER: environment minister Ricardo Salles recently told the UOL news website that the alert system “is not suitable for measuring deforestation, is inaccurate, and does not allow for comparisons.” On August 21, IBAMA issued a public call for bids from “companies that specialize in the daily supply of high-resolution satellite images that can be used to generate deforestation alerts.” The announcement followed the resignation of INPE director Ricardo Galvão after data from DETER indicated an 88% increase in deforestation between June 2018 and June 2019. In several press interviews, Galvão claimed to have reported the growing rate of deforestation to the Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovation, and Communications (MCTIC), which oversees INPE, and to the Ministry for the Environment, which is a client of DETER, but said that he was unable to achieve the same level of dialogue he had with previous governments. At the same time, IBAMA oversight seems to have lost its impetus—according to data from the institute itself published in the magazine Época, IBAMA fines for infractions fell 29.4% in the first seven months of the year compared to the same period of 2018.

Salles’s criticism does not take the distinctions between the roles of DETER and PRODES into account. DETER never aimed to calculate how deforestation is progressing over time—its aim is to interpret satellite images and quickly pinpoint active clearing locations in order to guide IBAMA. The alert system was created in 2004 to function as a complement to PRODES, whose annual report is released in December, with results from August 1 of the previous year to July 31. And although it is a useful tool for evaluating environmental policies, PRODES does not lend itself to identifying deforestation at its source. “PRODES sort of counts the number of bodies in the cemetery. In December, it announces what happened up to a year and a half earlier,” explains Câmara.

This limitation became most evident in 2004, when a lack of control in the Amazon led to increased deforestation of 27,700 km² that year. At the request of the Ministry for the Environment, INPE then developed its daily alert system. DETER uses a more flexible methodology than PRODES and has become more sensitive over time. Between 2004 and 2017, it used data from the MODIS sensor on NASA’s Terra satellite, issuing more than 70,000 alerts during this period. With this instrument, it was possible to detect forest cover changes larger than 25 hectares. The second version of DETER, currently in operation, identifies and maps deforestation with a minimum area close to 1 hectare. It achieves this by using images from the WFI sensor on the China-Brazil Earth Resources Satellite (CBERS-4) and the AWiFS sensor on the Indian Remote Sensing (IRS) satellite. The data is reported to IBAMA on a daily basis. Only areas larger than 6.25 hectares are disclosed to the public.

Felipe Werneck / Ibama

Logging on Pirititi indigenous land in Roraima, May 2018 Felipe Werneck / IbamaWhile PRODES identifies clearcut areas, DETER alerts include a number of different classifications. It shows whether soil is exposed and recognizes signs of mining activity. It also identifies evidence of forest fires and logging activities, whether it be selective logging, which leaves no specific pattern, or clearcut logging, which leaves a geometric pattern.

The methodology has limitations, which are not always fully understood. Real-time monitoring is never 100% accurate—if the view of a deforested area is obscured by clouds, it is only possible to detect a change when it becomes visible again to the satellite. In these cases, it is not possible to compare alerts from one month to the next, because the presence of clouds can mask the results. It is also not appropriate to group the alerts together, since the same area can be the subject of several alerts. “DETER can detect a deforested area and issue an alert. If nothing is done, the area may be further cleared before the next period, generating a new alert,” explains Gilberto Câmara. The alerts cease when the area is completely cleared and the information is recorded by PRODES. Fifteen years of experience shows that the trends identified by DETER are usually confirmed in the PRODES data, although they only register part of the deforestation. From August 2017 to July 2018, the alerts signaled deforestation of 4,500 km², but the official area was 7,500 km².

Eduardo Delgado Assad, a researcher at the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA) in Campinas, remembers the intense clearing that occurred in the “Arc of Deforestation” in the state of Pará when he was Secretary of Climate Change and Environmental Quality at the beginning of the decade. “Federal funding was suspended for the 44 most deforested municipalities. The result was that Paragominas went from the biggest deforester to an exemplary municipality in the recovery of deforested areas. DETER and PRODES functioned as an instrument of public policy.”

Similar systems

Replacing the current system with a private service is controversial. One feature of PRODES and DETER is that deforestation data can be cross-referenced against land type, such as private land, indigenous land, and conservation areas. “This helps us understand where the major focuses are—if they are in areas subject to land grabbing, for example. The information contributes to the creation of policies designed to curb or reduce deforestation,” says Krug, from INPE. Similar systems do not have the same potential. “Most other systems use lower-resolution images and automated data interpretation. They do not show how much of the rainforest has been cleared in each municipality, protected area, or indigenous land. These are high-resolution images without intelligence,” says Câmara.

INPE’s expertise in satellite imaging began to take off in 1974, when the institute spent US$1 million on General Electric’s image-processing system Image-100. In the following decade, researchers on INPE graduate programs developed two platforms—an image-processing system called Sitim and a geographic information system called SGI—which supported environmental projects such as a survey of the remaining Brazilian Atlantic Forest and a map of risk areas for planting corn, wheat, and soy, both conducted by EMBRAPA.

A major milestone in the institute’s efforts was its geographic information processing system (Spring), which unifies the processing of remote sensing images, maps, networks, and numerical terrain models. “This development was fundamental to learning how to analyze and interpret images. The Spring system united five applications in one and was considered one of the best in the world,” says Assad, from EMBRAPA. Another important development was the Queimadas program, which gathers data on wildfires and helps state agencies combat them.

According to Assad, INPE helped create a geoprocessing culture in Brazil. “In 1987, the field was nonexistent. Today, the industry is worth R$15 billion per year in Brazil, uniting monitoring and precision agriculture companies and an army of researchers—EMBRAPA alone has 16 geoprocessing laboratories. INPE trained a substantial proportion of the professionals working in the sector,” he says. Assad believes Brazil has unique experience in identifying the vulnerabilities of an enormous area of national heritage in terms of biodiversity and environmental balance. “This is the result of an extraordinary public project that has involved successive governments since the 1980s.”

Republish