The lack of coordination across institutions and programs and the absence of a long-term investment strategy are among the core reasons behind Brazil’s poor performance in international innovation rankings. These were the findings from an audit conducted from June to December 2018 and reported in May 2019 by the Department of External Control – Economic Development of the Brazilian Audit Court (TCU). The audit examined the activities of the Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovation, and Communications (MCTIC) and 10 other Federal agencies responsible for implementing research-funding policy in Brazil, including the Brazilian Funding Authority for Studies and Projects (FINEP) and the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES).

The report, developed by a team of seven TCU auditors led by deputy chairwoman Ana Arraes, shows that over the past two decades the Federal Government has attempted different mechanisms to connect academia to industry as a way of supporting innovation in Brazil. One example of these mechanisms is the Innovation Act of 2004, which established a framework for researchers from public institutions to collaborate on corporate projects, and outlined rules on the monetization of intellectual property resulting from those projects. In November 2005 the Federal Government introduced “Lei do Bem,” a set of tax incentives for research and development (R&D) to boost innovation. But the audit court found that these and other efforts to catalyze innovation have had only modest results.

This is not the first time the TCU has assessed programs implemented by science, technology, and innovation (ST&I) agencies in Brazil—there have been several audits on institutions in the sector in the past. A recent example was its review of the trademark and patent process implemented between 2012 and 2015 at the National Institute of Industrial Property (INPI). In 2011 the court also assessed initiatives undertaken by the then Ministry of Development, Industry, and Foreign Trade, now the Special Office for Productivity, Employment and Competitiveness under the Ministry of the Economy. It identified a variety of issues in government initiatives to advance an innovation agenda, including fragmentation, gaps, and conflicts that could compromise effective strategy execution.

The TCU audit in 2018 came to many of the same conclusions as from the previous assessment, especially in relation to innovation activities in Brazil. It drew attention to how ST&I funding volumes had grown since the early 2000s—the report came prior to recent developments in the context of the financial crisis. In tax-deducted funding alone, investment in ST&I went from about R$1 billion per year in the early 2000s to more than R$7 billion in 2013, according to the TCU, based on data from the Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA).

Pedro França / Agência Senado

A public hearing organized by the Senate CCT to discuss national broadband policy in 2017Pedro França / Agência SenadoR&D spending had also increased as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP): from 1.04% to 1.24% in the report period. The report also highlighted how 16 sectoral funds created in the late 1990s had helped to fund ST&I programs in several fields.

These funds formed what would become a new funding model for the sector. “This is an innovative mechanism designed to strengthen Brazil’s ST&I capabilities,” says physicist Ildeu de Castro Moreira, president of the Brazilian Society for the Advancement of Science (SBPC). The funds are linked to the National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development (FNDCT) and were originally intended, says Moreira, to provide a stable supply of research funding managed within a participatory, multistakeholder model. The TCU report indicates underfunding was not a problem in previous decades—the biggest issue was the lack of policy guidance on the use of those funds. “But now,” Moreira explains, “not only is a plan of action lacking, but 90% of FNDCT funding has been frozen [placed in a contingency reserve] and repurposed to pay off public debt, which undermines any long-term, strategic planning.” As a result, these and other innovation programs have failed to deliver expected results. The court auditors warn that Brazil is lagging other countries when it comes to innovation. This is clearly reflected in the country’s position in the Global Innovation Index (GII), an annual ranking published by Cornell University in partnership with Institut Européen d’Administration des Affaires (INSEAD), in France, and the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), in Switzerland. In the period 2016–2017 Brazil ranked 69th out of 127 countries; in 2019 it ranked 66th out of 126.

The main culprit identified in the auditors’ report is that Federal innovation incentive programs in recent decades have been highly fragmented and poorly coordinated. The TCU identified a total of 76 Federal initiatives in the last 20 years, all implemented without long-term coordination. For example, during the report period the MCTIC launched three different national plans of action and strategies to develop an innovation ecosystem in Brazil. However, according to the report, the ministry itself recognizes it failed to create mechanisms to coordinate and align these initiatives together. In other words, the Brazilian government has funded a large number of programs in recent decades without any kind of cross-program integration.

Asked to comment, the BNDES, one of the organizations mentioned in the TCU report, stated through its press office that it recognizes the importance of coordination among the different public and private actors in the national innovation ecosystem, and has signed cooperation agreements with several institutions engaged in innovation support. “BNDES has often worked in collaboration with FINEP, such as in developing the Inova Empresa program.” The development bank also cited its role in discussing and developing public policies to foster innovation, working with government ministries and agencies. FINEP declined to comment on the report.

According to the TCU, one of the consequences of inadequate strategic coordination has been incoherent and ineffective government spending. This has been exacerbated by the absence of adequate performance metrics and the inaction of the National Council for Science and Technology (CCT). Created in 1996, the CCT was meant to serve as an advisory body to the President in formulating and implementing policies for scientific and technological development. The TCU report found, however, that the CCT is poorly structured and understaffed, its meetings have been sparse, and its leadership in policy-making and priority-setting has been lacking.

The CCT held 13 plenary meetings and 112 subject-matter committee meetings from 2004 to 2019

Ildeu Moreira notes that CCT meetings have become increasingly sporadic since 2012—in all, 13 plenary meetings and 112 subject-matter committee meetings were held from 2004 to 2019. “Only two were during Michel Temer’s entire term [2016–2018],” he says. “A meeting scheduled for November last year under the current administration was postponed to a later date. We have continued to stress the importance of these meetings and of an active CCT.” He also notes that recent meetings have been less than productive. “There has been little effort by the government to listen to suggestions from different organizations and sectors, discuss issues in depth, and work together to build medium- and long-term policies.”

Luiz Davidovich, chairman of the Brazilian Academy of Science (ABC), says the council, like many of its counterparts elsewhere in the world, was created directly in response to demand from the scientific community. “The CCT was established with a mandate to assist the President in creating long-term public ST&I policies and coordinating the innovation policies that are in place or under development,” he says. “However,” he notes, “the CCT is far from exercising the leadership that other scientific advisory bodies around the world do.”

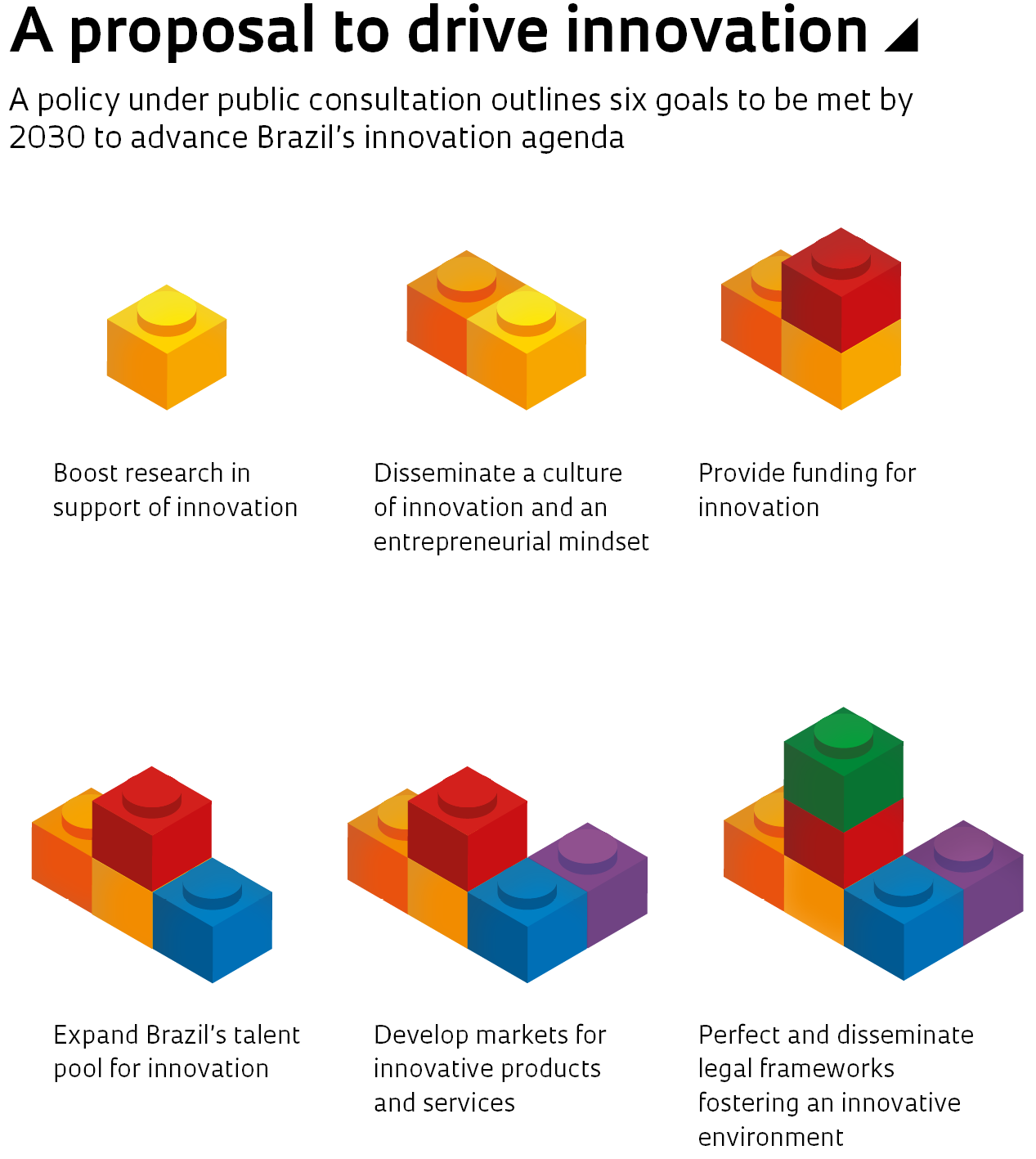

A policy under public consultation outlines six goals to be met by 2030 to advance Brazil’s innovation agenda

> Boost research in support of innovation

> Disseminate a culture of innovation and an entrepreneurial mindset

> Provide funding for innovation

> Expand Brazil’s talent pool for innovation

> Develop markets for innovative products and services

> Perfect and disseminate legal frameworks fostering an innovative environment

Innovation policies and programs in many countries are largely led by offices that are directly under the president or prime minister and are therefore able to influence the ST&I agenda, explains economist Fernanda De Negri of IPEA, who has done research about Brazil’s difficulties in producing and benefiting from innovation. “These offices are able to coordinate ST&I strategies across industry, academia, and broader society.” The US was one of the first countries to create an office to advise the President and coordinate ST&I activities across agencies and with the private sector. The UK, which ranked 4th on the 2018 Global Innovation Index, created the position of chief scientist—a personal adviser to the prime minister and their cabinet on ST&I topics—in the 1960s. Like the UK, Australia also has a chief scientist tasked with offering expert advice to its prime minister.

In 2015 the government of São Paulo, acting on a proposal submitted by FAPESP, announced the creation of chief scientist positions in each of the state departments. Their role is to make science-based recommendations on solutions to challenges facing departments (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue no. 236). More recently, in September 2019, the Ceará Foundation for Scientific and Technological Development Support (FUNCAP) launched a Chief Scientist program as a way to promote closer collaboration between academia and public managers. Teams of researchers, led by a chief scientist, will work at state-level departments and strategic agencies to develop scientific and technological solutions for the improvement of government services (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue no. 274).

In Brazil, explains Davidovich, the President or his/her designated representative is responsible for calling meetings and forming subject-matter CCT committees to implement national programs and decide on budget allocations according to established goals. “In the Brazilian system, Congress sets a ceiling for government spending and can also, in theory, repurpose funds in the Federal Government’s proposed budget, although in practice it changes things very little and leaves decisions on appropriations to the Executive Branch,” he explains. “ST&I policies need to be very clearly articulated if funding is to be applied effectively. Hence the importance of the Federal Government implementing a well-informed and coordinated national ST&I plan. If the CCT functioned as it ought to, it could play an important role in this regard.”

The system is different in countries like the US. There, Federal S&T spending is informed by assessments by government departments, such as Defense, Energy, and Health. The US has no dedicated S&T department, so ST&I budget appropriations are instead decided by congressional committees, which play a key role in distributing federal funding to different areas of ST&I (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue no. 261). These negotiations allow representatives from different agencies to defend their budget in Congress.

While the audit court’s report pinpoints many of the roadblocks to developing a strong innovation ecosystem in Brazil, it should not be taken as a final verdict. For De Negri, although the report does raise important issues, Brazil’s low levels of innovation also stem from structural factors that were not addressed in the audit, ranging from the low quality of basic education to the lack of an economic environment lending itself to innovation. “It will take more than an innovation policy to tackle these issues,” she says. “Without a comprehensive ST&I policy that sets long-term priorities and guidelines and engages different sectors, government programs to foster innovation will remain a patchwork of discrete initiatives.”

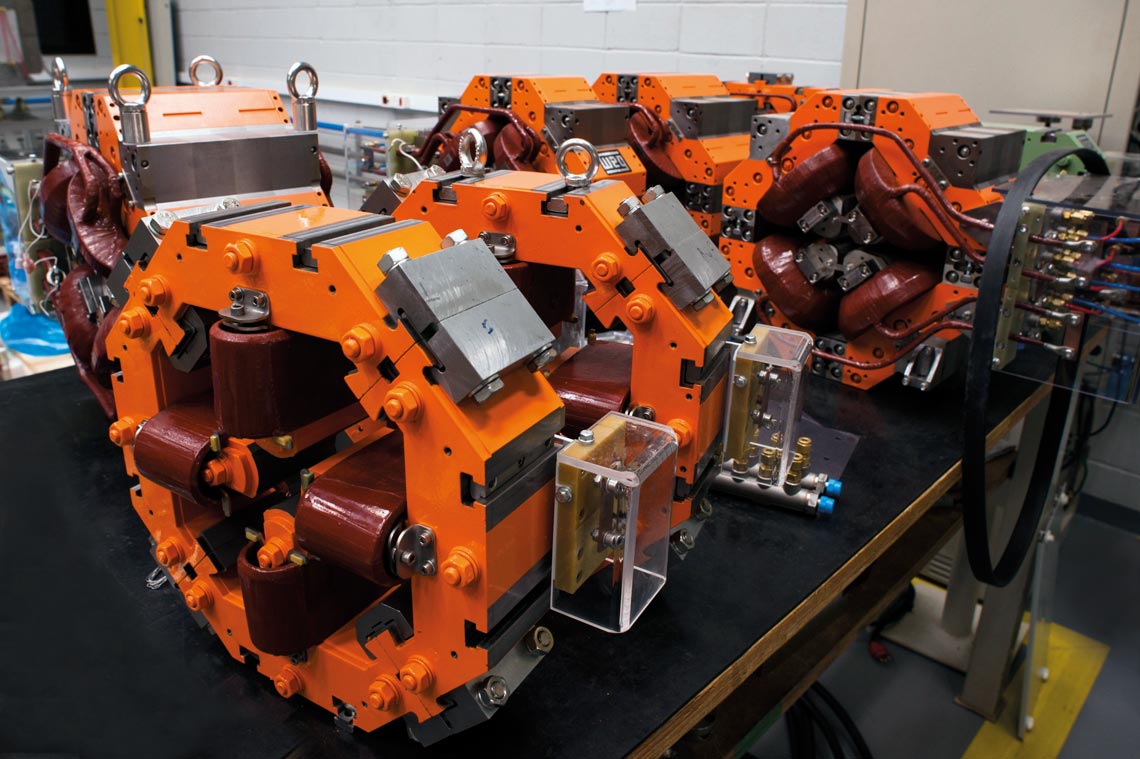

Léo Ramos Chaves

Brazilian motor manufacturer WEG’s production of parts for the Sirius synchrotron program illustrates how public investment in ST&I can drive innovation in industryLéo Ramos ChavesIn her view, effective strategies to build an innovation ecosystem in Brazil need to address aspects such as expanding and enhancing Federal investment in research infrastructure, reducing the capital costs of innovation investment, and better integrating Brazil’s economy with global production and technology value chains. It is not just about incentives, but about constructing a robust environment that fosters competition and greater access to these technologies. “Our sector has lost most from Brazil’s closed economy. We cannot access next-generation capital goods produced around the world,” says the researcher.

“The TCU report, as well as the Federal Senate Science and Technology Committee (CCT) reports on research funds in 2016, provides valuable insight that deserves more attention,” says Carlos Américo Pacheco, who chairs the Technical-Administrative Council (CTA) at FAPESP. “Assessments of ST&I policies have previously been made by academics and by IPEA. But these reports have been overly confined to the issue of limited funding. In the science and technology community, this has been a central concern.” What the TCU and the Senate Science and Technology Committee reports reveal, says Pacheco, is far more serious: weaknesses in public policies, failure to set priorities, dilution of research funding, and failure to measure results and coordinate initiatives. “In a sense, the shortage of funding is a consequence, not the cause, of the problem: the lack of clarity around the objectives and purposes of ST&I policy makes it difficult to secure buy-in from society and the government. The case being made is weak, as it is limited to treating investment in knowledge and innovation almost as a moral imperative.”

In an effort to address some of the problems, the MCTIC last November launched a public consultation on a new proposal for a national innovation policy. “The text is structured around six priority guidelines designed to revamp Brazil’s innovation ecosystem by 2030,” explains Marcelo Barros Gomes, of the Presidential Cabinet’s Office for Policy Review and Oversight. “After the public consultation period, these guidelines will be translated into objective strategies and action plans, and tracked against tangible targets and indicators,” he adds. One of the proposal’s main goals is to establish a coherent framework for initiatives implemented by MCTIC and other ministries. “We’re addressing innovation through a state policy that coordinates stakeholders involved within the Federal Government,” says Marcos Cesar Pinto, deputy head for public policy at the Presidential Cabinet’s Office for Government Affairs.

Marcelo Gomes explains that the new innovation policy proposal aims to address some of the issues raised in the TCU report. One initiative, for example, will strengthen the research needed to support innovation in Brazil through programs to expand the country’s research capabilities. “This will require predictable and stable government funding toward addressing strategic ST&I challenges.”

The proposal undergoing public consultation is also based on studies by the Center for Management and Strategic Studies (CGEE). Interviews and workshops were held with 30 stakeholders within the National ST&I System, including representatives from government, industry, startups, universities, development agencies, and research centers. “In addition, since September last year we have organized meetings and working groups with representatives from these and other sectors in different cities in Brazil to develop proposed guidance on research, development, and innovation initiatives over the coming years,” says Gomes.

Republish