Multi-role unmanned aircraft are increasingly being deployed for environmental monitoring, hotspot detection, and even direct fire suppression. In Brazil, state and municipal civil defense agencies have mainly used imported systems, but encouraging field results have fueled a wave of innovation—and a push to develop homegrown technology. At the University of São Paulo’s São Carlos campus, a team is developing a drone outfitted with advanced sensors and artificial intelligence (AI) systems to measure greenhouse-gas (GHG) concentrations, monitor environmental conditions in forested areas, and spot fire outbreaks. Two firms in the state of São Paulo—Xmobots, headquartered in São Carlos, and UAVI, based in São José dos Campos—have already brought wildfire-response drones to market.

“Our drone is designed to supplement existing monitoring systems—such as satellites, lookout towers and crewed aircraft,” explains mechanical engineer Glauco Caurin, who is leading the project at the Aeronautical Engineering Department at USP’s São Carlos School of Engineering (EESC). According to Caurin, drones bring a set of advantages that can make environmental surveillance more efficient. Satellites may pass over a given region only once or twice daily, but drone operators can tailor flight paths and revisit schedules to the specific risk profile of an area.

Fixed lookout towers detect smoke from a single vantage point and typically can’t pinpoint the precise location of the outbreak. Drones, by contrast, can capture imagery and volumetric gas measurements at multiple altitudes, generating micro-region-level data that sharply improves localization of GHG sources. “Compared with crewed aircraft, drones are far cheaper to operate—meaning more missions can be run on the same budget,” explains Caurin.

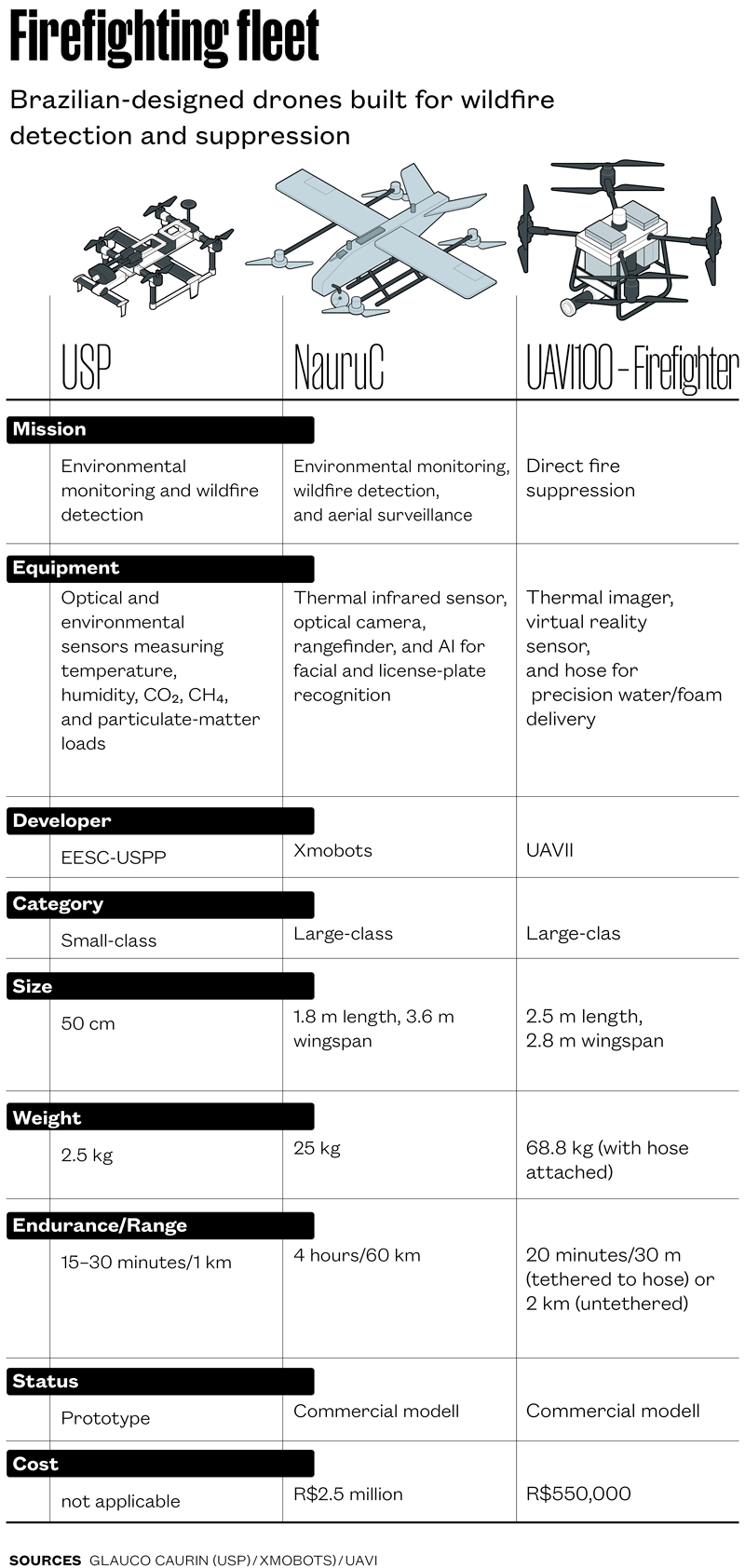

Developed with funding from FAPESP, the small-class USP-developed drone (see infographic below) uses four electric motors and features full vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) capability. A suite of optical and environmental sensors measures temperature, humidity, particulate loads, and concentrations of gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4). An onboard microcomputer, paired with an AI analytics system, processes the collected data to identify the origin of detected gas emissions. “By mapping the CO2 concentration gradient, we can indirectly infer the most probable location of a fire’s point of origin,” Caurin explains.

The GHG profile generated by the sensor suite and AI engine also offers insights into the overall health of the forest under observation. “A single flyover can tell us whether a reforestation program is being successfully implemented, with seedlings growing as expected, or whether it is a matter of greenwashing—in other words, using sustainability as a marketing ploy rather than for practical outcomes,” Caurin says.

A new winged version

The USP team is now developing a new, second-generation model. Alongside the rotors that enable vertical takeoff and landing, the new design will incorporate fixed wings, significantly reducing the energy required for horizontal flight. The upgraded drone is expected to stay aloft for nearly an hour, double the endurance of the current prototype. “To survey large areas effectively, we’re aiming for even greater endurance—on the order of 90 to 120 minutes,” Caurin explains. He adds that covering vast landscapes will ultimately require a coordinated fleet of drones.

The EESC team opted to outfit the drone with low-cost sensors to measure GHG concentrations. “They’re not ultra-precise, but they’re affordable and provide a useful signal of gas presence,” the researcher notes. “High-precision sensors can cost more than R$100,000. That’s a steep investment for hardware mounted on drones that can crash, break, or simply go missing.” The EESC group demonstrated both the drone platform and the performance of the chosen GHG sensors in a chapter of The Future of Electric Aviation and Artificial Intelligence, a book published by Springer Nature earlier this year.

The USP drone was originally developed as a component of a broader data platform for tracking GHG emissions across the Amazon. The project’s coordinator, physicist Paulo Artaxo of USP’s Institute of Physics, notes that current drone endurance remains limited and that sensor accuracy must improve before the system can fully meet the demands of forest monitoring. “Developing a domestically built drone for GHG measurements and forest-health diagnostics is an important first step,” Artaxo says. “But to achieve real operational value, the system would need several improvements, including higher-precision sensors and longer endurance.”

Even so, the technology package developed at São Carlos has already drawn interest from two companies that are negotiating licensing agreements to manufacture the drone. It has also caught the eye of the municipal Civil Defense agency, which has conducted field tests of the system in collaboration with the local Fire Department. “In wildfire response, drones equipped with gas-sensing instruments are invaluable,” says environmental engineer Pedro Fernando Caballero Campos, who heads Civil Defense operations in São Carlos.

Caballero notes that tracking gas concentrations before, during, and after a fire improves understanding of combustion dynamics and enhances prevention strategies. “It also lets us study atmospheric gases under varying conditions, and get a clearer picture of air quality and how it affects both human and animal health,” he adds.

Antonio Carlos Duad Filho / EESC-USP A prototype of the small-class drone developed at USP São CarlosAntonio Carlos Duad Filho / EESC-USP

Civil defense agencies in several Brazilian states—among them São Paulo and Mato Grosso do Sul—already deploy small-class imported drones for wildfire operations. Their onboard technology packages, however, differ from the system being developed at USP. Some units carry thermal imagers with infrared sensors; others combine thermal and visible-spectrum cameras. Priced between R$50,000 and R$100,000, according to vendors, these drones are used primarily to detect and locate heat signatures and to help guide fire-suppression crews in the field.

Larger, longer-endurance drones are also employed for forest and rural-area surveillance and for early detection of wildfire outbreaks. In Brazil, Xmobots—founded in 2007 by former students of USP’s Polytechnic School with funding from FAPESP—was an early pioneer in supplying drones for wildfire-monitoring missions. Since 2020, the São Carlos–based company has offered a model equipped with a thermal infrared sensor, an optical camera, and a rangefinder for real-time distance measurements.

Mounted on a platform with a full 360-degree field of view, these sensors are supported by an AI system capable of facial recognition and license-plate identification. This allows the drone to help identify individuals or vehicles potentially involved in unlawful activities. Beyond environmental monitoring and wildfire detection, the aircraft is also deployed for surveillance missions.

The drone is a winged VTOL system measuring 1.86 meters long with a 3.64-meter wingspan, developed as part of the company’s Nauru drone family. With a four-hour endurance and a 60-kilometer operational radius, it can reach altitudes of up to 3,000 meters. “It’s the only drone in Brazil authorized by ANAC—our national civil aviation authority—to operate above 400 feet (about 192 m) and to fly at night,” says commercial director Thatiana Miloso.

The Nauru 500C is used primarily to patrol public areas, commercial forest plantations, and agricultural operations. According to Xmobots, citing data from the Brazilian Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock (CNA), wildfires inflicted roughly R$14.6 billion in losses on Brazil’s agribusiness sector between June and August 2024. Xmobots is now working on an upgraded version of the drone. “We’re enhancing the system’s performance by adding environmental and gas-analysis sensors,” says electrical engineer Leonardo Gomes, a project manager at the company.

Xmobots Xmobots’s NauruC model used for environmental monitoring and wildfire detectionXmobots

Water-and foam-jet capability

Drones are also being used for direct fire suppression. Leading the way in Brazil is the UAVI100 “Firefighter,” launched this year by UAVI, a company based in São José dos Campos’s Science Park. The aircraft features eight motors, two batteries, a 20-minute endurance window, and a payload capacity of 150 kilograms.

The system lifts a hose roughly 6 centimeters in diameter to heights of up to 30 m and can project a precision stream of water or foam out to 25 m. The hose remains connected at ground level to a fire engine or hydrant, ensuring continuous flow. The drone also carries a thermal imager and a virtual reality sensor, giving operators a real-time field of view.

The first two UAVI100 units were delivered in May to the Manaus Fire Department. “Our drone has already seen action in real fire-suppression operations. Three additional units are on order,” says UAVI’s managing director Ricardo Pietro. “Fire departments in Paraná, Goiás, and Mato Grosso have also placed orders, and we’ve already received inquiries from as far away as Portugal,” he adds.

The drones are used mainly for urban firefighting along forest edges and buffer zones. New versions are under development, including models with nozzle-control systems and payload modules designed to carry chemical fire suppressant or silica-fabric fire blankets. “Our R&D team collaborates closely with fire-service personnel to deliver equipment tailored to users’ different needs,” Pietro notes.

The story above was published with the title “Firefighting drones” in issue 356 of October/2025.

Projects

1. CEPOF – Optics and Photonics Research Center (n° 13/07276-1); Grant Mechanism Research, Innovation, and Dissemination Centers (RIDCs); Principal Investigator Vanderlei Salvador Bagnato (IFSC-USP); Investment R$51,786,666.96.

2. Research and Innovation Center for Greenhouse Gases – RCG2I (n° 20/15230-5); Grant Mechanism Engineering Research Centers (CPEs); Agreement BG E&P Brasil (Shell Group); Principal Investigator Julio Romano Meneghini (USP); Investment R$25,376,639.63.

3. Design of a certifiable avionics system for unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) for civil applications (n° 13/50946-8); Grant Mechanism Innovative Research in Small Businesses (PIPE); Agreement FINEP PIPE/PAPPE Subsidy; Principal Investigator Giovani Amianti (Xmobots); Investment R$876,283.32.

Book chapter

CAURIN, G. et al. “Unmanned aerial vehicle cooperation for the monitoring of greenhouse gases”. In: KARACOC, T. H et al. The future of electric aviation and artificial intelligence. Switzerland: Springer Nature, 2025.

Republish