The São Paulo State Public Archive (APESP) in November launched a software platform that will give researchers and citizens more comprehensive and searchable access to the institution’s digital collections. These comprise over 700,000 documents that were either produced by state government agencies or are otherwise historically significant, including collections from former governors, local political and cultural personalities, institutions such as the Historical and Geographical Institute of São Paulo, the São Paulo Maternity Hospital, newspapers, and political parties.

A total investment of R$6.9 million went to expanding data storage and processing capacity, purchasing equipment, and upgrading the power supply system. The resulting Digital Public Archive has recently been rolled out in beta form and can be accessed at atom.arquivoestado.sp.gov.br. This platform will provide a one-stop location hosting all existing and future digital archives. The next step will be to expand the number of available documents and store them so they are easily accessible.

One of the most awaited collections is from the State Department of Political and Social Order, or DEOPS, a police intelligence agency created during the dictatorship. This collection contains over 300,000 case files and was first added to the Archive in the 1990s (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue no. 207). Some of the digitization work was done as part of research projects on topics such as immigration, political repression, and the presence of Jews in Brazil. Several of these projects were funded by FAPESP, including a number led by historians Maria Luiza Tucci Carneiro and Maria Aparecida Aquino at the University of São Paulo (USP) between the late 1990s and early twenty-first century. Now, an additional 2.5 million DEOPS case files are slated to be digitized.

The Archive has set up a new repository to host copies of paper records as well as digital-only records produced by São Paulo government agencies, including case files and fiscal information. In 2019 the government created a paperless program, called SP Sem Papel, for managing digital records, with all electronic documents now classified for retention purposes at the time they are produced. “Roughly 20% of government records have historical value and need to be appropriately identified and preserved indefinitely; 50% can be disposed of in the short term—up to 2 years; and 30% have longer retention periods, from 5 to 80 years. This is all managed by the Archive,” explains APESP director Thiago Nicodemo, a professor of history at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP). Retention periods are established in time charts prepared by the Archive with representatives from each agency.

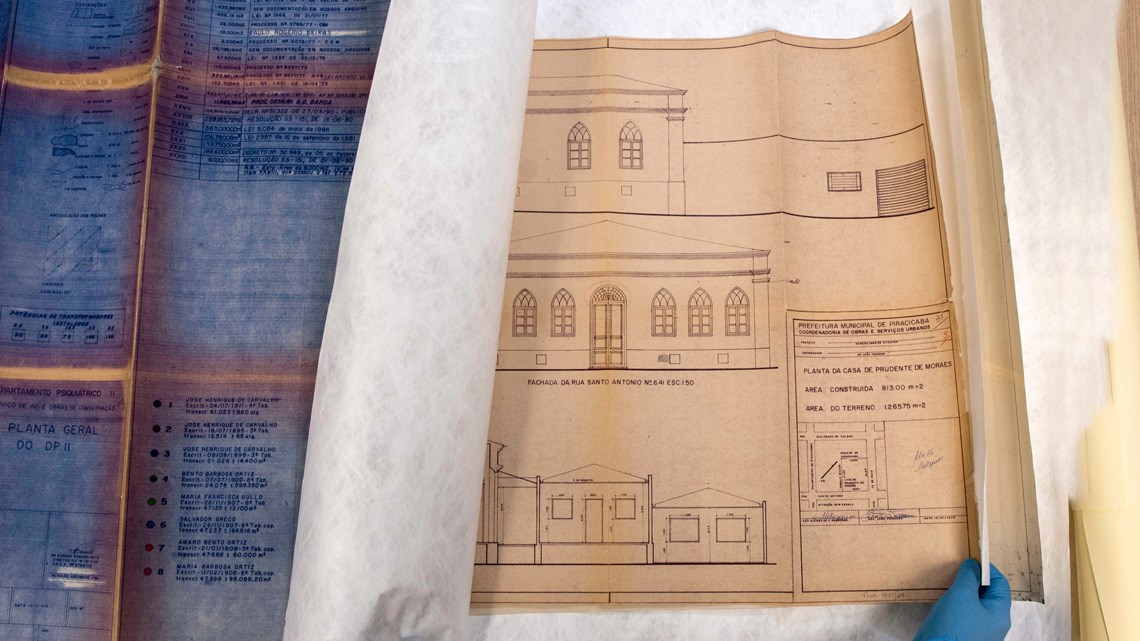

Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESPDocuments from the State Board of Historical Heritage (CONDEPHAAT), now added to the Archive’s blueprint sectionLéo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

Part of the investment in the digitization effort has gone to upgrading more than 70 open-source software programs that are helping reorganize the collections. These programs have been developed as scripts that allow a long list of tasks to be run with a single command. One of the programs can be used to automatically rename large batches of files; this allows them to be quickly catalogued so they are easily searchable.

The Archive collections were digitized at different times, and each is available on a separate website. With all files now catalogued under a common standard, the new platform will allow users to search for all available documents on a given topic. “A search about the 1924 or 1932 revolutions, for example, will return copies of battalion newspapers; letters and telegrams from a collection at the Historical and Geographical Institute of São Paulo; and a large case file from the São Paulo Appeals Court, complete with related photos. The Archive’s railway and other collections will be similarly integrated,” says sociologist and archivist Carlos Menegozzo, head of APESP’s Research Support and Outreach Center. Not all collections will be available online. The recently archived medical records from the Juquery Psychiatric Hospital contain sensitive information that will not be uploaded to the platform, but can be viewed in person.

Claudia Bauzer Medeiros, a researcher at the UNICAMP Computing Institute and a coordinator of the FAPESP eScience and Data Science Research Program, says the Archive initiative is notable for the sheer volume of information being made available and for the rigorous methodology being used to organize that information. “A vast amount of documents from different sources needs to be catalogued using international standards to ensure they are preserved over time. At the same time, they need to be readily accessible and searchable, including online, but without infringing the privacy and confidentiality rights of data subjects.” Repositories created by universities and other institutions face similar challenges in storing and preserving research data, says Medeiros. “It’s not just about storage. All data needs to be accompanied by metadata conforming to international standards so it is readily identifiable and can be cross-referenced with other data sets,” she explains. “Providing open-access and well documented data is an integral part of internationally recognized best practices in open science. In a session in November 2021, the UNESCO General Conference adopted a Recommendation on Open Science that applies to all member-States. FAPESP has been at the forefront of open science initiatives in Latin America.”

Maintaining the collections has been a learning process for the Archive managers. “Initially our digital collections were stored in directories without using established standards or conventions,” says sociologist Camila Brandi, technical director at APESP’s Digital Preservation and Outreach Department. “It became clear that we would need systems and governance to ensure that documents are properly preserved and their authenticity is assured. They need to be in the right format for storage and need to be controlled and documented. This provides an audit trail to determine whether anyone has accessed a folder and inadvertently or intentionally erased a document, so we can then restore it to its original condition.”

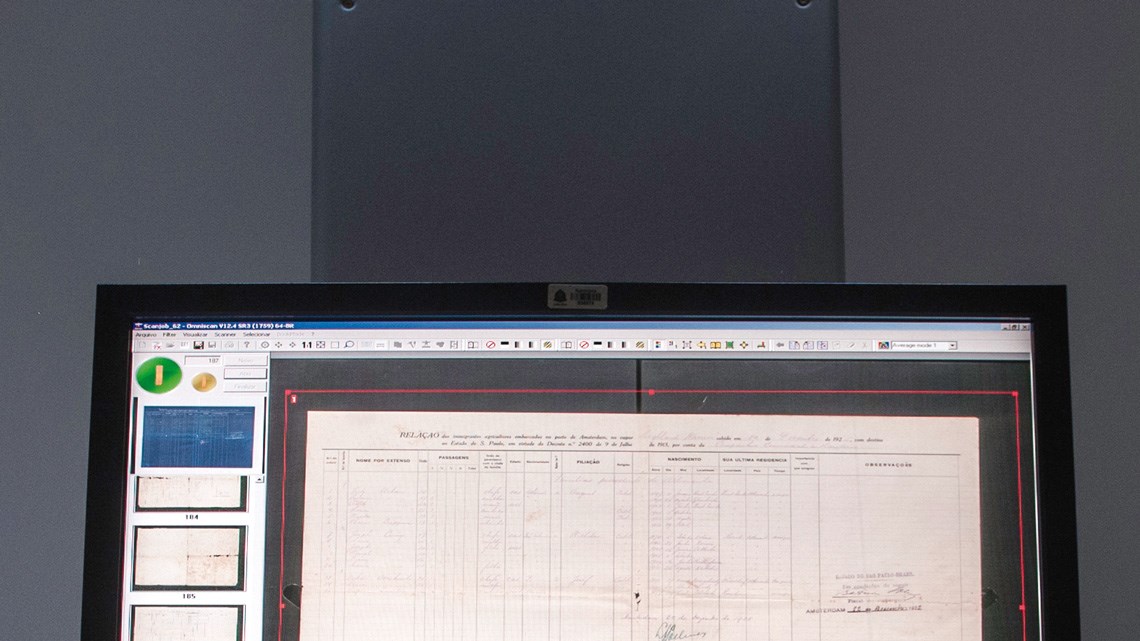

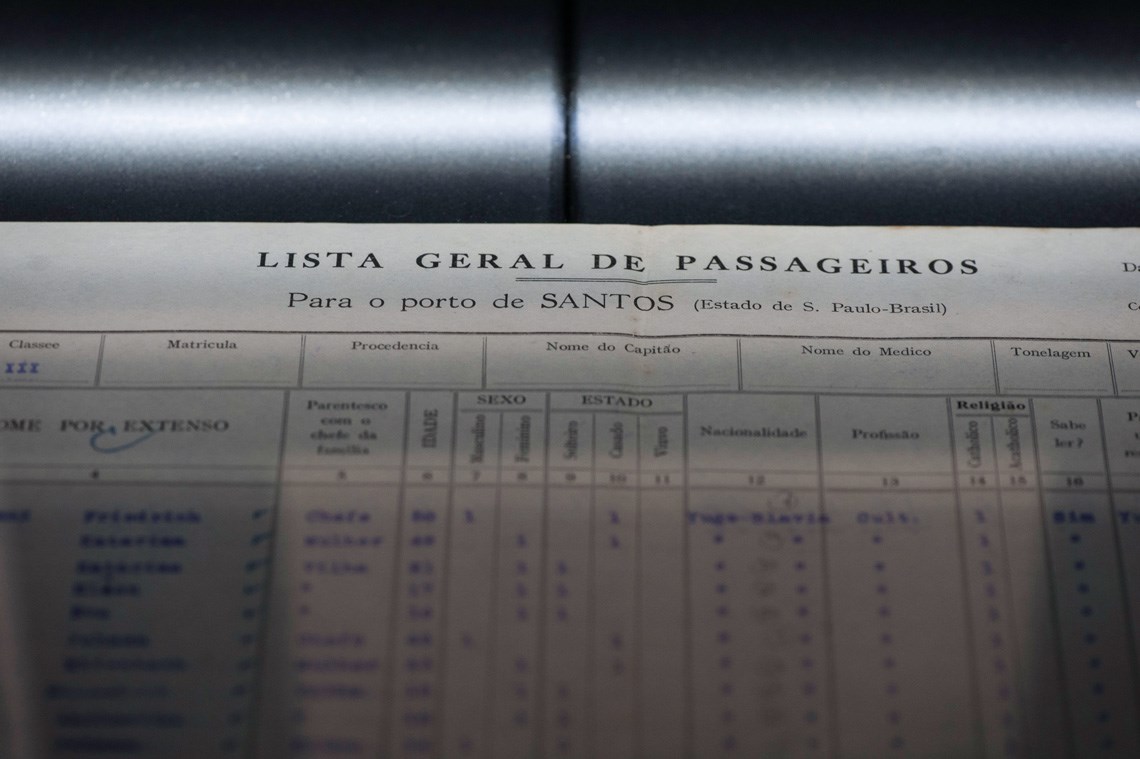

Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESPA scanner digitizing a list of passengers arriving in São Paulo in the previous centuryLéo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

For scanned paper records, such as copies of now-defunct newspapers like Última Hora, medical records describing the history of leprosy in the state of São Paulo, or records from the Federal Police Foreigner Section, the challenge was processing these documents and making them searchable without affecting their integrity. Some collections were processed using Optical Character Recognition (OCR) tools that allow users to search them for keywords; others were not processed, which makes it difficult for users or researchers to find and retrieve the information they need. “After two decades of digitization projects, we now have a better understanding of the risks and benefits of these technologies,” says Brandi. “Everyone has at some point lost a memory stick with important information, or had a family photo corrupted and made unusable. With organizations it’s no different. We’ve learned that it takes more than just digitizing collections to preserve them. They need to be managed so they retain their integrity and authenticity over time.” According to Thiago Nicodemo, prior experience has taught the Archive managers to be more selective in deciding what needs to be digitized. “We spend a lot of money in Brazil and globally on digitizing document collections, and we now realize that it needs to be done more judiciously.

Historian Ieda Bernardes, director of the São Paulo State Archive Management Department, notes that APESP’s ongoing transformation is partly aimed at avoiding past mistakes. “Different technologies have been used to organize document archives. In the 1950s, microfilming emerged as a solution to improve access to documents. Digitization has been used for similar purposes over the last 20 years. The problem is that scanned collections were initially produced in the same disorganized fashion as their paper counterparts,” says Bernardes. Some archive managers made the mistake of disposing of physical files and keeping only their digitized versions, many of which ultimately became either corrupt or inaccessible due to their storage media becoming obsolete.

Bernardes explains that while a digital preservation program may increase efficiency, it also incurs higher costs compared to preserving paper archives. “If you think digitization saves money you’d be mistaken. It requires continuous investment in upgrades—hardware and software become obsolete in a matter of years—and monitoring document conditions,” she says.

The North American Space Agency (NASA) spends a significant part of its budget on preserving information obtained from space research and missions, notes Medeiros. “In a conversation I had a few years ago, a NASA director described the challenge it was to preserve data assets, with 30% of the agency’s funds going toward data management. Constant investment is needed for upgrades and especially for training human resources.” This investment is crucial, she says. “It may not be cheap, but the loss of these records would cause incalculable damage. We’d be throwing away a treasure trove of information.”

Republish