In 1759, following the expulsion of the Society of Jesus from Portugal by order of Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo (1699–1781), the future Marquis of Pombal and Secretary of State of the Portuguese Empire, the Jesuits were forced to leave Brazil. One of them, José Basílio da Gama (1741–1795), then a novice, sought refuge in Rome around 1760, where the religious order remained active. In Italian intellectual circles, the young man, born in the present-day town of Tiradentes, southeastern Brazil, was often asked about the gold mining trade in his homeland. In response, he composed a lengthy poem in which he claims to reveal the “unvarnished truth” about local mining, of which he had been an eyewitness. “Gold is the most prized among the world’s precious metals. Earth produces it as ore, and the gold mine yields it as metal after it is extracted with great toil. Now it is my duty to sing of it: a challenging task for the poet, but a pleasant undertaking,” he announces at the beginning of Brasilienses aurifodinae, his debut poem.

An excerpt from As minas de ouro do Brasil

Written in Latin between 1762 and 1764 and unpublished until now, the poem has now been translated and published under the title As minas de ouro do Brasil (The gold mines of Brazil) in a bilingual edition produced by EDUSP. The text provides a rare account of society and the gold-based economy in eighteenth-century Brazil, offering a wealth of information about prospecting processes, the tools used, and the enslaved labor employed in gold mining.

A literary treasure trove, the manuscript was discovered in the 1980s by Vania Pinheiro Chaves, now a professor at the School of Languages and Literature at the University of Lisbon, Portugal. The Brazilian researcher and scholar of the works of Basílio da Gama found the only known manuscript of Brasilienses in the collection of bibliophile Rubens Borba de Moraes (1899–1986) in Bragança Paulista, São Paulo State. At the time, Chaves received photographs of the poem from the collector for publication. While there are a number of gaps in the history of the manuscript, it is believed to have arrived in Brazil by way of a Brazilian diplomat, Ivan Galvão, who purchased it in Italy in the 1930s. Following his death, Brasilienses ended up in a bookstore, Livraria Kosmos, in Rio de Janeiro and was later purchased by Moraes in the 1960s. Shortly before his death, Moraes donated his collection to businessman and bibliophile José Mindlin (1914–2010) and his wife, Guita (1916–2006). In 2005, the couple donated the collection to the University of São Paulo (USP), which established the Guita and José Mindlin Brasiliana Library (BBM), where the manuscript is currently housed.

Chaves suggests that Brasilienses may have been created as a “letter of introduction” for the poet to gain admission to the Accademia degli Arcadi, one of the most prestigious literary academies in Europe at the time. “Basílio da Gama was eager to present himself as a Brazilian who had something to share with the world. Brasilienses is a work of undeniable value, which served the dual purpose of highlighting Brazil’s greatest source of wealth and informing Europeans about a reality they were unaware of,” says Chaves. The excellent condition of the manuscript, with neat handwriting and no corrections, suggests that the copy was ready for printing. For reasons unknown, it never went to press.

The translation of the original, containing 1,823 verses in Latin, was undertaken by Portuguese classicist Alexandra de Brito Mariano, a professor at the School of Human and Social Sciences at the University of Algarve, Portugal. Mariano had researched the work for her doctoral thesis, defended in 2005 at the same institution. As part of her research, she had studied old mining treatises and delved into the fields of history and geology. The result is a prose version in Portuguese that is easily understood by contemporary readers. “Translating Brasilienses demanded extensive research, as the poem is filled with numerous details about the mining process, including underground mining, which posed greater risks to the enslaved. Basílio da Gama recounts how they entered the mines carrying lanterns fueled by whale oil,” says Mariano.

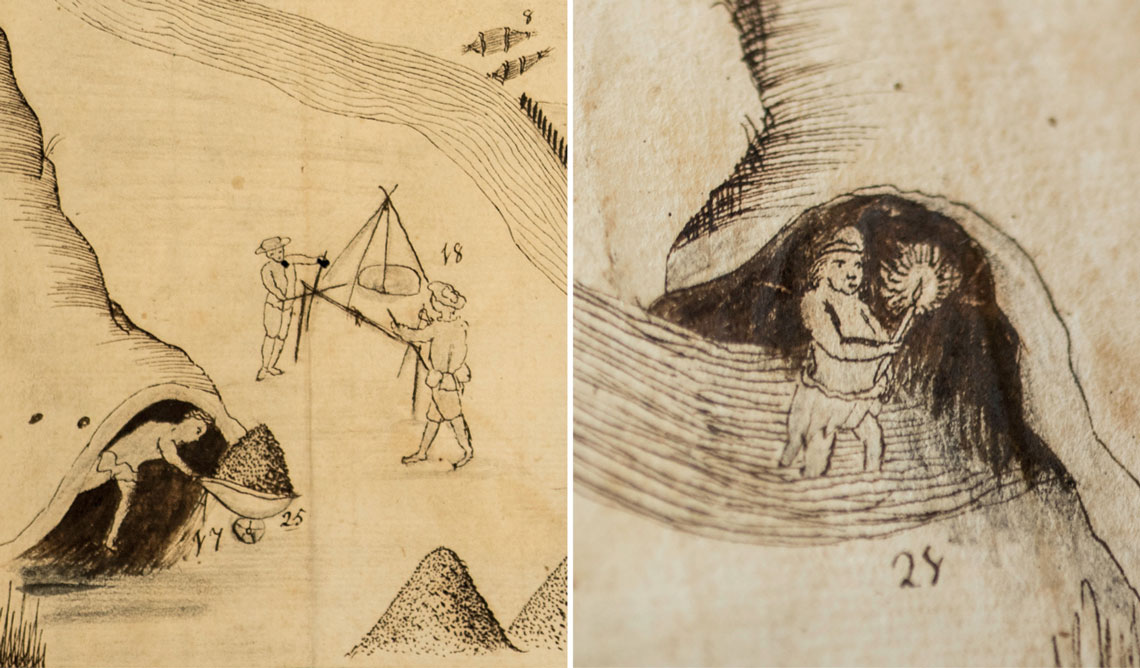

Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESPDetails in the illustration show a cart and a pulley used to transport ore (on the left) and an enslaved person with a torch searching for goldLéo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

Amid descriptions of diseases, articles of clothing, and labor contracts signed between masters and the enslaved, the author references classical authors such as Virgil (70 BC–19 BC) and contemporary scientists like Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) and Isaac Newton (1643–1727), whom he had studied as part of his Jesuit education. The Latin text is interwoven with words in Portuguese and Tupi. “The translation process was slow and painstaking. I began during my doctorate, and have since made countless revisions. But there were also very poetic parts that were a joy to translate, such as where the author compares the veins of gold to the veins of the human body, drawing parallels to the field of medicine,” the translator recounts.

A key figure in Luso-Brazilian Arcadism, Basílio da Gama is best known for his epic poem O Uraguai (1769), a defining piece of Brazilian eighteenth-century literature that has been analyzed by scholars such as Antonio Candido (1918–2017) and Sérgio Buarque de Holanda (1902–1982). The five-canto poem, which chronicles the defeat of the Jesuits in the Guaranitic War (1753–1756) in southern Brazil, explicitly praises the Marquis of Pombal. When he published the work, Gama was living in Portugal and was no longer a Jesuit. He had joined the religious order in 1757 in Rio de Janeiro, and after the expulsion of the Society of Jesus from Portuguese domains, he went to complete his studies in Europe around 1760. However, Gama was unable to gain admission into the order in Rome. The reason remains controversial. “Some suggest this was due to resistance from the Society of Jesus itself. What is known for certain is that, in Rome, even without completing all his vows, he was treated as an abbot,” writes historian Júnia Ferreira Furtado from the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), in the book’s afterword.

As Furtado continues, his “writing of an ‘Ode to Dom José I’ [then King of Portugal] in 1765 indicates his new intention to sever ties with the Society of Jesus and to fully align himself with Pombaline politics.” Two years later, Gama returned to Brazil to establish a chapter of the Accademia degli Arcadi in the former town of Vila Rica, now Ouro Preto (MG). Shortly afterward, in 1768, he was forced to return to Portugal with a group of former Jesuits and was sentenced to exile in Angola, but was ultimately pardoned. “It is believed that the pardon was given on behalf of Maria Amália, Pombal’s daughter, who was grateful for a poem in which Basílio celebrated her marriage,” says Chaves from the University of Lisbon.

“Basílio da Gama was very adept at political maneuvering,” says Carlos Versiani dos Anjos, an independent researcher with a doctorate in literary studies from UFMG. “O Uraguai was written in the context of his rapprochement with Pombal, of whom Basílio da Gama became an assistant,” adds dos Anjos, who in 2021 published an article in the journal Teresa, published by USP’s School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences, in an edition commemorating the 250th anniversary of the poem. According to Furtado, the great hero of the saga is Gomes Freire de Andrade, who had commanded the Portuguese army in the Guaranitic War and had mentored Gama in his youth. In the text, the author “sings of the Portuguese victory in the Guaranitic War and praises Pombal’s policies, including those directed against the Jesuits,” writes Furtado.

With its unrhymed decasyllabic verses, O Uraguai captivated authors like Machado de Assis (1839–1908), who wrote a sonnet in honor of Lindoia, the heroine of the epic. The famed author of Dom Casmurro also planned to write a biography of the Arcadian poet. “Basílio da Gama gained admirers but also many detractors from a moral and ethical perspective. He was considered a traitor by the Jesuit order because of his association with the Marquis of Pombal,” notes Augusto Massi, a professor of Brazilian literature at FFLCH-USP. Among them was Father Lourenço Kaulen (1716–1799), who wrote a virulent critique of the poet which, according to Massi, greatly influenced subsequent critical perspectives. “In ‘Resposta apologética ao poema intitulado O Uraguay’ [An apologetic response to the poem titled O Uraguay; 1786], Kaulen accused Basílio da Gama of lacking mastery of Latin. He also expressed suspicions about Brasilienses aurifodinae and questioned how the author had gained entry into the Accademia degli Arcadi — a highly prestigious institution in Western literary culture — at such a young age. It was a form of retribution against the poet for defending the Marquis of Pombal’s policies,” continues Massi.

Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESPThe Brasilienses aurifodinae manuscriptLéo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

Similarly, historian Pedro Calmon (1902–1985), during the bicentennial celebration of Basílio da Gama at the Brazilian Academy of Letters in 1941, described the poet’s Latin as that of a “schoolboy.” Literary critic Wilson Martins (1921–2010), in História da inteligência brasileira (History of the Brazilian intelligentsia; Cultrix, 1976), argued that the young Basílio da Gama’s Latin verses were merely “homework exercises.” “Certainly, these people did not read Brasilienses but simply repeated hearsay about the poem. The manuscript was mentioned, but few had truly read it because it was not widely accessible,” concludes Massi. According to the researcher, future studies on the book might alter Basílio da Gama’s position in literary history, which once seemed firmly established. His bibliography has also been enriched with new perspectives, following the recent discovery by Massi himself of several contemporary documents — including an unpublished commentary by the Italian poet, physician, and typographer Vincenzo Benini (1713–1764), who praised the author’s linguistic talents.

With its insights into economic, political, and cultural life in colonial Brazil, Brasilienses may attract interest not only from literary scholars but also from historians, anthropologists, economists, linguists, and other researchers. However, as Furtado from UFMG notes, Brasilienses sometimes aligns with recent historical research, while at other times, it diverges from it. For instance, when listing the mechanisms available to the enslaved to achieve freedom, such as accumulating financial savings, Basílio da Gama provides insights for historians exploring why manumissions became widespread in Minas Gerais in the eighteenth century. In other parts of the poem, however, he seems disconnected from reality, as when he asserts that “the masses are content with cheap food and coarse cotton clothing.”

According to Chaves from the University of Lisbon, the poem contains various elements that could intrigue contemporary researchers, especially concerning the issue of slavery. “Brasilienses is a trove of information about the condition of enslaved Black people in Brazil at the time, with Basílio da Gama vividly recounting the violence of the human trade. It is a poem that will provide fodder for many future studies and will likely prove as significant as O Uraguai, says Chaves.

Book

MARIANO, A. B. (trans. & org.). As minas de ouro do Brasil ‒ Brasilienses aurifodinae. São Paulo: Edusp, 2024.

Scientific journal

CHAVES, V. P. et al. (org.). 250 anos de O Uraguay. Teresa. São Paulo, Brasil. Vol. 1, no. 21. 2021.