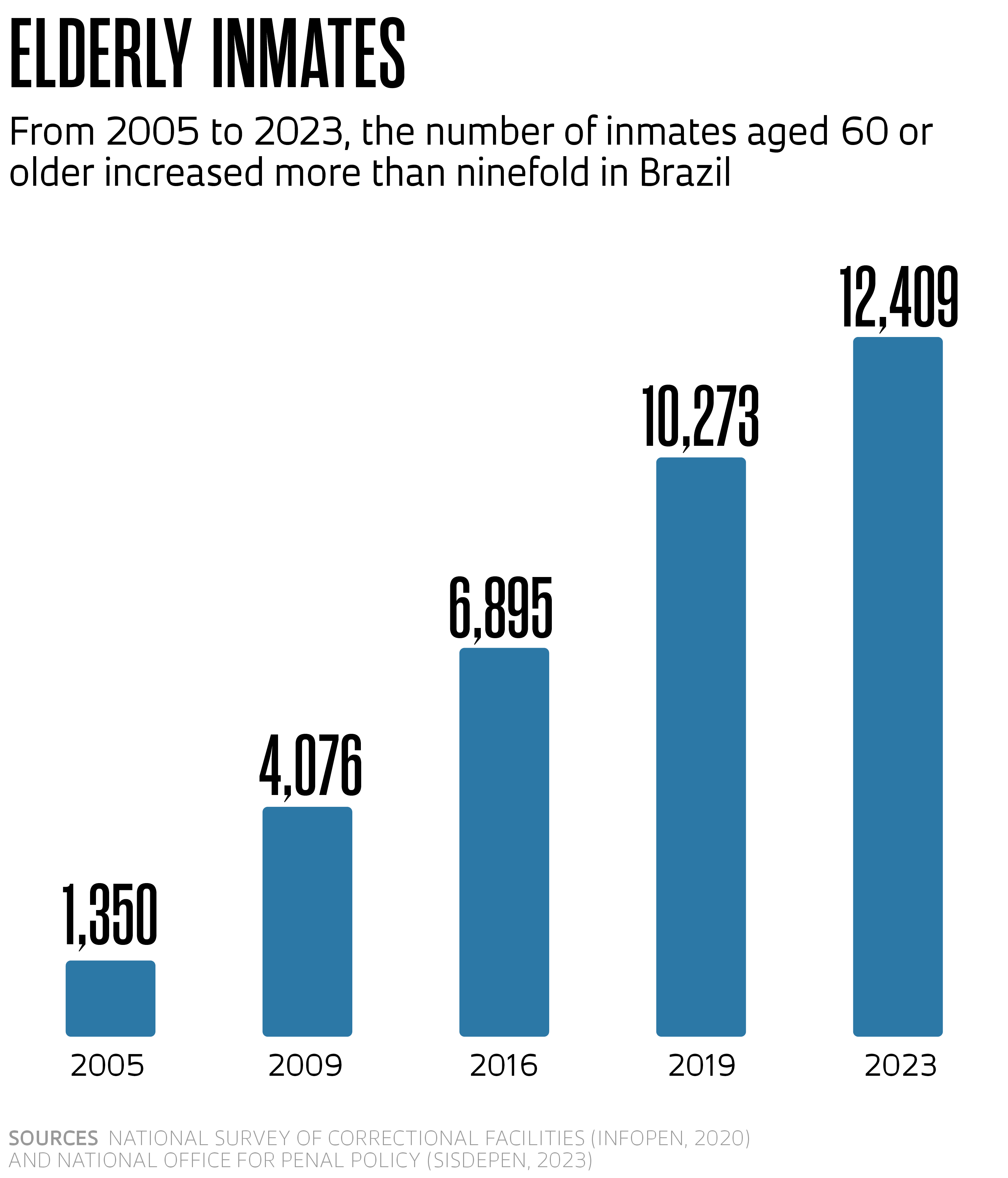

The contingent of elderly inmates in Brazilian prisons has grown more than ninefold (819%) from 2005 to 2023, now totaling 12,400 people, or 1.9% of the country’s prison population. Yet, proportionally, the share of elderly individuals across the country’s 1,300 prison facilities remains low, and this underrepresentation has obscured a world of untold stories and needs that have often been neglected by policymakers and academic researchers. To shed light on their predicament, a study led by sociologist Maria Cecília de Souza Minayo and psychologist Patricia Constantino, from the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation’s National School of Health Policy (ENSP–FIOCRUZ), assessed the living and health conditions of elderly inmates in Rio de Janeiro’s prisons.

Funded by the Rio de Janeiro State Research Foundation (FAPERJ), the study involved 11 specialists and included inputs from the Rio de Janeiro State Public Prosecutor’s Office. The research, using quantitative and qualitative analyses, investigated the situation of 647 men and 35 women over the age of 60 held in 33 male and 5 female maximum-security facilities between 2019 and 2020. During their field research, they found Rio de Janeiro’s prisons held a total of 724 men and 39 women aged 60 to 88 among their inmates. The research findings were published in the book Frágeis e invisíveis – Saúde e condições de vida de pessoas idosas privadas de liberdade (Fragile and invisible: Health and living conditions of elderly inmates), released in May by Editora Fiocruz.

– Brazilian prisons increase risk of illness and violent death

– Female prisoners have poorer health than the general population and are often abandoned by their families

– Most crimes committed by men over 60 involve sexual assault

Last year, Rio de Janeiro’s prison system housed a total of 44,300 people, of whom 42,800 were men and 1,400 were women. “The growing contingent of elderly inmates can be partly explained by the rise in incarceration across all age groups, as well as by the aging of the Brazilian population, but further investigation is needed to identify other underlying causes,” suggests Minayo. Rio de Janeiro, she says, used to have a dedicated prison in Niterói for individuals aged 60 and over, which offered workshops and daily outdoor time. Doctors visited the facility twice a week, along with dentists and nurses. However, in 2014, the state government decided to reallocate the elderly inmates to other prisons throughout Rio de Janeiro State, repurposing the Niterói facility to house convicted police officers. Since then, the situation has worsened for elderly inmates, according to Minayo.

The FIOCRUZ study found that 94.5% of elderly inmates in Rio de Janeiro were men, averaging 65.7 years old. Women made up 5.5% of the total and averaged 63.8 years old. Most identified as Black or mixed-race (58.6%) and reported having children (92.7%). About 59% had not completed high school, and 15% were illiterate. A significant portion of elderly inmates (74.6%) had been incarcerated for less than five years, and 37.4% of them reported not receiving visits. More than half (52.5%) said health issues interfered with their daily activities. The most commonly reported health problems were high blood pressure (affecting 56.9%), frequent constipation (23%), and diabetes (20%).

Urinary incontinence and poor dental health were cited as the main causes of suffering, with 60% of the elderly lacking most of their teeth. Complaints about improper diet, overcrowded and unhygienic cells, lack of medical care, as well as lacking eyeglasses and exercise, were similarly commonplace. Cognitive tests were also conducted to assess the mental health of 540 individuals of both sexes. Of the total, 130 showed cognitive and mental problems, especially depression. Ana Laura Marinho Ferreira, a legal scholar who conducted field research in women’s prisons as part of her master’s at FIOCRUZ in 2021, notes that, although elderly women showed relatively good physical health, their emotional health was in a more critical state compared their male counterparts.

In 2022, Ferreira published the book Velhice atrás das grades: Condições de saúde de mulheres idosas nas unidades prisionais do estado do Rio de Janeiro (Old age behind bars: Health conditions of elderly women in Rio’s prisons; Dialética, 2022), reporting on the findings from her master’s research. In her study, she identified the contrasting profiles of elderly female inmates and their younger counterparts. In the younger group, the majority are Black or mixed-race, while most of the elderly identified as white. “The most common offense among younger women was drug trafficking, while among the elderly, fraud and embezzlement are also frequent,” says Ferreira. Another difference is that, in general, while younger women are abandoned by their families during their time in prison, elderly women tend to receive visits from family members. “Despite these differences, there is generally a respectful relationship among female inmates. The older women are often called moms and grandmas and receive help with their daily routines,” noted Ferreira.

Inmate solidarity in Brazilian prisons was also the subject of a doctoral thesis defended in 2018 by nursing professor Pollyanna Viana Lima at the State University of Southwest Bahia (UESB). During two years of fieldwork, she visited four prisons in Bahia to interview 31 inmates over 60 years old. She held individual and group conversations — either face to face or through prison intercoms — and reviewed their health records. In one facility, 20 people took turns in each cell to sleep on the three available mattresses. “However, there was one elderly man with serious back problems who was allowed to use a mattress every night,” she notes. According to Lima, almost all of the elderly individuals interviewed during her research were illiterate and had worked as farmers since childhood. “They were keen to have some kind of occupation in prison. One of the most sought-after roles was janitor, which grants status by allowing inmates to move throughout the entire facility,” she says.

Minayo notes that elderly inmates often experience multiple physical and psychological issues that the prison environment tends to exacerbate. In Rio de Janeiro, these frailties were more pronounced among the 16 individuals over 80 years old, and especially among the six who were over 88 years old. The study also identified 40 dependent elderly individuals living in critical condition within the state’s prison system. “They were unable to walk to the cafeteria or to use the bathroom, remaining permanently bedridden, often having to relieve themselves in bed,” says Minayo. The prisons in the study did not offer age-specific services or care for these individuals, who relied on Good Samaritanship from fellow inmates. For people with this type of dependency, one proposed short-term solution is to train inmates to act as caregivers, with this work granting credits toward sentence reduction. “Despite the degrading conditions, the interviewees expressed positive expectations for the future: 81% of them expect to have a satisfying personal life after leaving prison,” adds Minayo.

In some cases, elderly individuals over 70 years old or those who are seriously ill can request to serve their sentence under house arrest, according to Irene Cardoso Sousa, a public prosecutor in the Pernambuco State Public Prosecutor’s Office. However, those who have committed heinous crimes are generally not eligible for this benefit. Plus, many inmates cannot access lawyers to submit the petition in court. Sousa completed her master’s degree at FIOCRUZ in Pernambuco in May 2024, investigating the living conditions of 529 elderly inmates in 19 correctional facilities in Pernambuco. There, 20% of individuals over 60 years old serve their sentences under house arrest. Because most prisons are located along the coast, the families of elderly inmates who live inland face difficulties in visiting them. “In addition to the psychological impacts of feeling abandoned, this creates a range of other practical problems. One is that prisons do not provide items such as toothbrushes, soap, and bedding to inmates, so those who do not receive visits are deprived of these essentials,” explains the researcher, noting that more than 30% of elderly inmates in Pernambuco prisons are in this situation.

Alessandra Minervina dos Santos Lopes, a nurse at the São Paulo State Department of Penitentiary Administration, completed her master’s degree in 2020 at the Marília School of Medicine (FAMEMA). As part of her research, she investigated the criminal backgrounds and health conditions of 270 elderly inmates serving sentences in 27 São Paulo prisons. About 60% of them had some type of disease, with cardiorespiratory conditions being the most common. “Sadness from broken family ties, fear of having nowhere to go after leaving prison, and feelings of regret were some of the most commonly expressed sentiments in the interviews,” says Lopes. Whereas sexual assault was the main reason for elderly men’s convictions in prisons in Rio de Janeiro, Pernambuco, and Bahia, homicide was the most common felony among inmates in Lopes’s study.

Aline van Langendonck

Aline van Langendonck

Contrasting with the findings of her research, the men’s prison in Florínea, São Paulo, where Lopes currently works, is recognized as a model for its treatment of vulnerable people, including the elderly, the homeless, and LGBTQ+ people. There, Lopes serves as technical health director and leads a team providing care to inmates. Of the 1,300 inmates, 15 are elderly, with two of them over 80 years old. “With good infrastructure and well-trained medical staff, even during the pandemic, when prisons faced heightened health risks, especially among the elderly, we had no deaths under our watch,” says Lopes.

Health measures in Brazilian prisons are regulated by the National Policy on Comprehensive Health Care for Inmates (PNAISP), established in 2014 by a joint ordinance from the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Justice. Brazil’s Penal Execution Code, Law No. 7,210/1984, mandates the provision of a range of activities across education, employment, and health to promote the social reintegration of inmates. “However, the PNAISP only mentions the need for special attention being paid to elderly or disabled individuals without outlining specific policy measures,” explains Constantino from FIOCRUZ. Her research in Rio de Janeiro found that only two prisons had implemented these guidelines: Tiago Teles de Castro Domingues and Juíza Patrícia Lourival Acioli, both located in São Gonçalo.

Brazil’s Elderly Statute, which regulates the rights of individuals aged 60 and over, mandates their protection in situations where they are the victims. However, it is silent on situations where they are the offenders, according to an analysis by Rose Aparecida Ferreira Ribeiro, a legal scholar on the Special Commission for Elderly Care of the Brazilian Bar Association, Rio de Janeiro chapter. Ribeiro, who earned her doctorate from Fluminense Federal University (UFF) in 2021, with her research exploring the situation of elderly inmates in 13 prisons in Rio de Janeiro, was part of the team that conducted the FIOCRUZ study. “The Penal Code, enacted in 1940, was amended after the Elderly Statute was promulgated, but it only incorporated changes related to elderly people as victims of crimes, neglecting to address situations where they are the perpetrators,” says Ribeiro.

During visits to the 38 correctional facilities in her study — both male and female prisons — Constantino reports that in all of them, she found people who had to swallow food without chewing due to lacking teeth, had poor vision for lack of glasses, or smelled of urine and feces for lack of adult diapers. There was a particular case that both Constantino and Ribeiro cited as the most notable. It involved a 67-year-old illiterate man. He described himself as a professional thief who had spent his life in and out of prison. He did not know how many more years he would spend in prison, never received visits, and had no access to medication. He recounted how one day a piece of concrete fell on his foot, crushing two of his toes. Unable to get medical care, he spent months in pain, with his foot necrotic and numb. One night, rats entered his cell and chewed at his festering toes. It was only after this incident that he finally received medical care to treat the wound.

Drawing on these interviews, the FIOCRUZ study identified a set of priority needs for elderly inmates in Rio de Janeiro’s prisons, which could inform improvements in other states as well. The need for a more balanced diet (92.8%), the provision of medications — especially maintenance medications (89.3%) — and effective healthcare (81.6%) were some of the most urgent needs the study identified. Another measure that could have an immediate impact on the lives of elderly inmates is the provision of dentures, canes, walkers, and glasses. “While these people are in prison for crimes they have committed, it is still essential to ensure their human rights are upheld while incarcerated,” argues Minayo. As a general recommendation, the study advocates for creating dedicated prison wards for the elderly with appropriate infrastructure, including access ramps and grab bars in corridors, adapted bathrooms, and basic sleeping comforts.

The story above was published with the title “Elderly and marginalized” in issue 342 of august/2024.

Scientific articles

LIMA, P. V. Memórias de pessoas idosas encarceradas sobre o trabalho. Revista NAU Social. Vol. 13, no. 25. Salvador, 2022.

LOPES, A. M. dos S. et al. Idosos privados de liberdade: Perfil de saúde e criminal. Revista Kairós-Gerontologia. 25(1), 73–91. São Paulo, 2022.

GREENE, M. et al. Older adults in jail: High rates and early onset of geriatric conditions. Health Justice. Feb. 17, 6 (1): 3, 2018.

Books

MINAYO, M. C. de S. & CONSTANTINO, P. Frágeis e invisíveis: Saúde e condições de vida de pessoas idosas privadas de liberdade. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Fiocruz, 2024.

RIBEIRO, R. A. F. O seguro morreu de velho. Rio de Janeiro: Lumen Juris, 2024.

FERREIRA, A. L. M. Velhice atrás das grades: Condições de saúde de mulheres idosas nas unidades prisionais do estado do Rio de Janeiro. São Paulo: Dialética, 2022.

Report

Procedimentos direcionados à custódia de pessoas idosas no sistema prisional. Secretaria Nacional de Políticas Penais. Brasília: Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública, 2023.