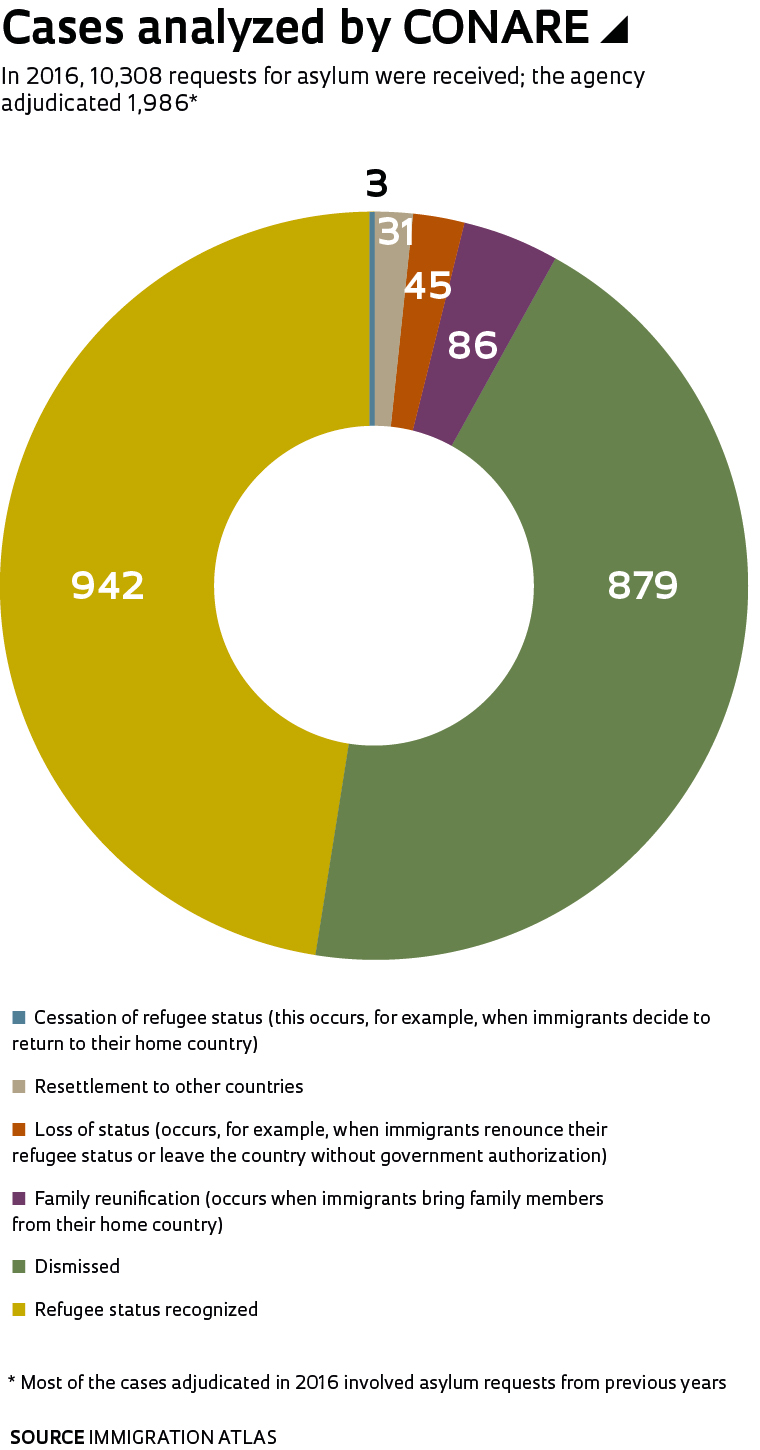

Between 2010 and 2017, requests for asylum in Brazil rose from 966 to 33,000 per year. Although at the beginning of this decade Haitians led all nationalities in the number of requests (442, or 46%), today, an influx of Venezuelans makes up the majority of the petitions, with a total of 17,000 applications sent to the Brazilian government last year. The data come from the National Committee for Refugees (CONARE) and are published in the Atlas temático do Observatório das Migrações em São Paulo – Migrações internacionais (Thematic atlas of the migration observatory in São Paulo: International migrations) developed by the Elza Berquó Center for Population Study at the University of Campinas (NEPO-UNICAMP) and released at the end of 2017. In the assessment by the researchers who drafted the document, the exponential growth can, to some extent, be interpreted as a result of the growing barriers immigrants face upon entering European Union countries and the United States. However, it also reflects the peculiarities in Brazilian immigration legislation, which makes seeking asylum the most reliable route for certain groups of foreigners to legally gain entry into the country. Adopting this strategy, however, far from secures their residency status in Brazil. The entire immigration process is marked by uncertainty.

Until the end of last year, the Foreigner Statute, defined during the military dictatorship and in effect since 1980, regulated the Brazilian migratory policy according to logic based on national security. Rosana Baeninger, a NEPO researcher and professor at the Institute of Philosophy and Human Sciences (IFCH) at UNICAMP, explains that the statute established certain conditions under which foreigners could obtain permanent or temporary visas in Brazil. These conditions varied according to bilateral agreements between specific countries, but certain circumstances gave migrants the right to residency, such as marriage to Brazilian citizens, the birth of children within Brazilian territory, or offers of employment. The statute prohibited those who entered without a visa from regularizing their status after already entering the country. “Reciprocity agreements allowed them to stay for up to 90 days, as tourists. After this period, many immigrants were legally undocumented, which restricted their access to certain rights,” explains Baeninger.

For South American immigrants, the situation began to change with the 1991 establishment of Mercosul, a regional integration process in which all South American countries currently participate, except for Venezuela, which was suspended from the bloc in 2017. “Mercosul allowed citizens of member countries to request temporary residence and work in Brazil,” Baeninger observes. When the New Immigration Law went into effect last November, foreigners of certain nationalities acquired the right to regularize their status without the need to leave the country, as had previously been the case. “The new legislation seeks to facilitate the establishment of residence for groups of migrants emigrating for humanitarian reasons, or for individuals with low levels of education, something that did not exist in the previous law. However, since all of its resolutions are not yet defined, foreigners do not know for sure the best way to have their presence in Brazil regularized.” She believes that both the past limitations of the Foreigner Statute as well as the uncertainties of the new law have caused some immigrant groups to bet on seeking asylum as a way to increase their chances of remaining legally in Brazil.

Department for Justice and the Defense of Citizenship of the São Paulo State Government

Immigrants seek work and documentation at a state government processing center in São PauloDepartment for Justice and the Defense of Citizenship of the São Paulo State GovernmentAsylum is governed by the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. It is this document that establishes standards for the treatment of this type of immigrant, defined in different ways by the signatory countries. In Brazil, asylum is governed by Law No. 9474/97. Enacted 20 years ago, it was not directly affected by new immigration legislation. To have their refugee status recognized, immigrants must prove that they suffer from “well-founded fears of persecution on grounds of race, religion, nationality, social group, political opinion, or grave and widespread human rights violations” in their home country.

Once the application is registered, the immigrant becomes entitled to all rights of the regularized citizen, such as temporary residence, a work permit, and medical care through the government’s Unified Health System (SUS) as well as a guarantee they will not be deported. The process for requesting asylum is free, unlike the visa application process. The requests are judged by CONARE, an interagency institution that also includes the Federal Police, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and non-governmental organizations. “Requests for asylum have been taking a minimum of two years to be decided,” says Gustavo da Frota Simões, a professor of international relations and coordinator of the Sérgio Vieira de Mello Chair at the Federal University of Roraima (UFRR).

Once their request for asylum has been filed, immigrants secure rights to receive work permits as well as medical care through the government health system

The entry process of Haitians since 2010 can help us understand how, under certain circumstances, seeking asylum can function as a strategy for entering Brazil. Haitian immigrants arrived after the 2010 earthquake that resulted in the deaths of 316,000 people in their Caribbean homeland. The first immigrants crossed the border through the states of Acre and Amazonas. In 2010, 442 Haitians sought asylum. In 2011, there were 2,500. While awaiting adjudication, they all had the right to work permits and the right of residence. “The Brazilian government did not recognize the Haitians as refugees. However, it identified that they were immigrating for humanitarian reasons and created a visa so that they could have their status regularized in Brazil. This visa would serve those who were in Haiti with the intention of emigrating and applying from the Brazilian embassy in their country,” explains economist Duval Magalhães Fernandes, professor of the Postgraduate Program in Geography at the Pontifical Catholic University of Minas Gerais (PUC-MG). He adds, however, that initially the government limited the number of these visas it granted to 1,200 per year. “This fact led to conditions of chaos on the doorstep of the Brazilian embassy in Port-au-Prince and further increased the numbers of immigrants arriving along the northern border who requested asylum,” recalls Fernandes. He adds that for Haitians who requested asylum and had their request denied, the government granted permanent residence visas. “At no point were the Haitians in the country under illegal conditions. So, requests for asylum became a mechanism for obtaining legal residency status in Brazil,” Fernandes notes. Between 2012 and 2014, requests for asylum by Haitians jumped from 3,300 to 16,700.