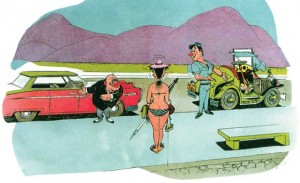

The Reproduction from the book Caricaturistas brasileiros 1836-1999automobile had just “arrived” in Brazil, in 1892, with the brothers Alberto and Henrique Santos-Dumont, when just a few years later, in 1903, one of the first automobile accidents in the country occurred. It involved the abolitionist José do Patrocínio e and his friend Olavo Bilac, to whom he had just lent his car, newly arrived from France. After trying to learn to drive for a few kilometers and causing many pedestrians to panic, the Parnassian poet slammed the car into a tree. “This only happened because I wasn’t baptized. With no religion and these bad roads, progress is impossible”, Patrocínio allegedly exclaimed. The story is typical of how automobiles were introduced in Brazil, transforming the power of driving and national progress and becoming for a few a source of power and authority for decades. “For the elite, the car was the perfect tool with which to achieve order and progress. Motoring, in this context, was to create a modern and conflict-free country. It was an icon of the growth of a democratic, developed and modern state”, explains the historian and Brazil specialist Joel Wolfe, from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and author of the newly released book, Autos and progress: the Brazilian search for modernity (Oxford University Press).

Reproduction from the book Caricaturistas brasileiros 1836-1999automobile had just “arrived” in Brazil, in 1892, with the brothers Alberto and Henrique Santos-Dumont, when just a few years later, in 1903, one of the first automobile accidents in the country occurred. It involved the abolitionist José do Patrocínio e and his friend Olavo Bilac, to whom he had just lent his car, newly arrived from France. After trying to learn to drive for a few kilometers and causing many pedestrians to panic, the Parnassian poet slammed the car into a tree. “This only happened because I wasn’t baptized. With no religion and these bad roads, progress is impossible”, Patrocínio allegedly exclaimed. The story is typical of how automobiles were introduced in Brazil, transforming the power of driving and national progress and becoming for a few a source of power and authority for decades. “For the elite, the car was the perfect tool with which to achieve order and progress. Motoring, in this context, was to create a modern and conflict-free country. It was an icon of the growth of a democratic, developed and modern state”, explains the historian and Brazil specialist Joel Wolfe, from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and author of the newly released book, Autos and progress: the Brazilian search for modernity (Oxford University Press).

“In order to achieve this, the group disregarded social realities, and focused on maximizing the potential of the car as a vehicle for progress and civilization. There was an entire symbolic line of discourse that put cars in the position of a modern representation of the entrepreneurial spirit of the past, of the pioneering expeditions and the pioneers, thus encouraging a sort of communion with modern nations, in particular with the United States”, states the historian Marco Sávio, a professor at the Federal University of Uberlândia (UFU) and author of A cidade e as máquinas [The city and the machines] (Annablume/Fapemig). Nevertheless, although cars were consumer goods to which only a minute portion of the population had access, they drew the attention of the government and large parts of the budget in favor of highways and asphalt in cities. “It was a reflection of the interests of a small group of people who wanted to enjoy the pleasures of motoring, an idea of an automotive society where moving around was free of any impediment”, analyzes Sávio. It was the so-called “possible utopia”, in the words of the São Paulo city mayor, Firmiano Pinto, who back in the 1920’s advocated asphalting São Paulo to harbor cars, even if there were only a few, to the detriment of society’s more pressing needs.

“It was the ideal of a conflict-free society in which moving about freely was the chief symbol of status and freedom. The motorists of this elite gave themselves the right to transit above good and evil, an abject amorality that caused deaths. It was the privilege of the machine over the right to put public space to other uses”, says the researcher from UFU. Here again, we encounter the “lessons” from Bilac’s accident, totally disregarding the people around him, comfortable in his “superior” position as a motorist, and from Patrocínio’s annoyance at the “guilt” of the authorities that failed to provide him with the “fundamental” conditions to drive without being hindered by anything. “Ever since, there has been a pattern based on the idea of domination and of the natural and incontestable right to use the city spaces for traffic, with the power of resorting to force whenever something gets in the way of the sacred right to free and unimpeded traffic”, notes Sávio.

“It is striking that the automobile was reinvented as leveling tool in the United States, but that, in Brazil, it became primarily an element of distinction, the sign of an intricate scale of social inferiority or superiority”, observes the anthropologist Roberto Da Matta, a professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio) and author of the research study “Equality in Traffic”, now transformed into the book Fé em Deus e pé na tábua: como e por que o trânsito enlouquece no Brasil [Faith in God while stepping on the gas: the how and why of Brazil’s maddening traffic] (Rocco). “The barbaric behavior in traffic results less from road works and material improvement issues than from everyone feeling special, superior and entitled to privileges and priorities that justify negligence and impatience with the general norms, which materialize in the form of traffic lights and pedestrian crossings”, he comments. “The automobile is an option for those who are in harmony with the aristocratic style of avoiding contact with the lowly plebs, with the poor people, coarse and common, since the time of the litters and palanquins. Our preference for individualized forms of transportation is retrogression. On the other hand, the developmental wave of the mid-twentieth century made it possible for us to enjoy the delirium of owning a car as the crowning of individual success. We moved toward the individualization of means of transport thinking only about our individual dimension, disregarding collective needs and norms. For the anthropologist, there is a historical absence, that dates back to the way in which cars were introduced into Brazil, of a full and egalitarian awareness. This is the fruit of colonial vices, precisely in the space in which modernity, supposedly acquired with cars, demands that it be underscored by and built through equality. “It is this shock of hierarchical expectations: those who see themselves as ‘richer’ have a ‘more expensive’ car, are ‘white’ and thus, expect their superiority to be acknowledged, clashing with the imposition of equality, that applies to all and that demarcates the universe of the ‘street'”. This is what produces the general feeling of chaos and stress in our traffic, he says.

Reproduction from the book A revista no BrasilAccording to Da Matta, the paradox that enhances our “stress” is that no trick can be used and nothing can be done to overcome the equality that underlies the public environment in which we move once we leave our homes. “We blame the government and thereby waste the entire learning process of patience that might improve our behavior in this area”, he analyses. Bilac and Patrocínio arise again, even when religion and gasoline are mixed together. “Hence the ‘faith in God while stepping on the gas’. The latter is evidence of the most typical side of our public conduct, the indicator of individual wishes, represented by haste and impatience whenever the path is obstructed by a crowd of strangers. Strangers that we do not see as equals and that are ‘obstacles’ in our way. It is a vision of ourselves as special beings, endowed with a singular position and, until proof to the contrary, a position that is elevated and protected within the system, because of our close ties with the Supreme Being”, says the anthropologist. “In Brazil, motoring acquired the features of an ideology, a promise to cure all the domestic evils. For the first time in Brazilian history, technology was embraced as a tool of economic, political and social transformation of society. This technology was to become useful to demolish the barriers to peaceful and orderly national integration. The automobile was to destroy the obstacles standing in the way of capitalist development and provide the basis for the establishment of a true Brazilian culture and identity”, says Joel Wolfe, the Brazilian specialist.

Reproduction from the book A revista no BrasilAccording to Da Matta, the paradox that enhances our “stress” is that no trick can be used and nothing can be done to overcome the equality that underlies the public environment in which we move once we leave our homes. “We blame the government and thereby waste the entire learning process of patience that might improve our behavior in this area”, he analyses. Bilac and Patrocínio arise again, even when religion and gasoline are mixed together. “Hence the ‘faith in God while stepping on the gas’. The latter is evidence of the most typical side of our public conduct, the indicator of individual wishes, represented by haste and impatience whenever the path is obstructed by a crowd of strangers. Strangers that we do not see as equals and that are ‘obstacles’ in our way. It is a vision of ourselves as special beings, endowed with a singular position and, until proof to the contrary, a position that is elevated and protected within the system, because of our close ties with the Supreme Being”, says the anthropologist. “In Brazil, motoring acquired the features of an ideology, a promise to cure all the domestic evils. For the first time in Brazilian history, technology was embraced as a tool of economic, political and social transformation of society. This technology was to become useful to demolish the barriers to peaceful and orderly national integration. The automobile was to destroy the obstacles standing in the way of capitalist development and provide the basis for the establishment of a true Brazilian culture and identity”, says Joel Wolfe, the Brazilian specialist.

“The automobile arrived in Brazil and was consolidated here as a major achievement of civilization, the victory of human science over nature. This worked especially well for the São Paulo state elite, for whom cars would fulfill a key role in the conclusion of the history of pioneering achievements, a second stage in the construction of the Brazilian nation, no longer by conquering territory, but through the presence of automobiles and highways”, states Sávio. This was the “neo-pioneering” line of thinking embraced by Washington Luis, mayor and governor of São Paulo and author of the famous sentence, “Governing is building roads”. He invested in the modernization of the transport infrastructure, building 1,326 kilometers of new roads, and taking this love of “good roads” to the federal administration when he became President of the Republic in 1926. “With him and the São Paulo state elite, the automobile turned into something more than an alternative means of transport; it became the paradigm of ‘being from São Paulo state’. The general mentality of these men advocated overcoming the national and state ‘backwardness’ by building roads capable of quickly linking the capital with the inner state areas, so that all the power and wealth of the São Paulo state civilization might influence the transformation of the hinterlands of Brazil”, Sávio adds. “Funnily enough, the coffee elite, which benefitted greatly from the linking of the national infrastructure and the export economy, popularized the machines dangerously, which would soon challenge the liberal economic model. After all, the car unveiled the possibility, for the first time, of unifying the nation and thus, unsettling the predominance of São Paulo state vis-à-vis the national State”, says Wolfe. One element that reflected this new trend, created thanks to the cult of automobiles, was the Federal Roads Law, passed in 1927.

“This law encouraged the states to request federal funds to build roads, provided that these highways were part of a national motoring system. This was yet one more novelty that clashed with the long republican laissez-faire tradition on the economic front. Little by little, the car opened the way toward a centralized State”, continues the Brazilian specialist. This was aided by the American automakers that established themselves in the country, such as Ford and General Motors. “They were considered necessary tools for progress, capable of transforming disorderly immigrants from abroad and from the hinterlands into a disciplined working class that would transform the country”. Or, as Henry Ford himself wrote in Today and tomorrow: “The automobile will make the great nation of Brazil. The natives, though unfamiliar with machinery and any form of discipline, will soon assimilate the world of the production line”. “By encouraging car transportation through the inner-state areas of Brazil, the American companies helped to change the mental geography of the country, besides encouraging road building, with a view to increasing the demand for vehicles, which was to be expanded to the entire nation”, explains Wolfe.

“The strategy of Ford Brazil was always to disseminate the idea that a car is functional and that it was the ideal answer to the conditions in Brazil, always tying its brand to the pressing issue of highways. These concepts were music to the ears of the elite of a state with very few roads suitable for motoring”, adds Sávio. Concurrently, the advertising aired by these companies reinforced the conservative modernization of the automobile, driven by the hierarchy of society, according to which the owners of less valuable cars, such as the Ford Model T, were beginning to be seen as an inferior class of citizens, only barely above the immense mass of pedestrians threatened with chaotic traffic. “I almost threw myself under the wheels of an automobile. It was a Ford. However, I chose not to. A very ordinary death”, explained the suicidal character of Automóvel de luxo [Luxury Automobile] (1926), a book by the modernist Mário Graciotti.

According to Sávio, these were the fruit of a movement that started in 1909 in São Paulo, when the transport projects began better reflecting the desires of a small group for automobiles to start taking over the position once held by streetcars as the center of transportation concerns. “The emergence of bodies such as the São Paulo Automobile Club, in 1908, which brought together the most important citizens of the state, helped to relegate public transport to a secondary plane. The streetcar, for instance, was seen as an ‘inadequate’ means of transport, since it placed, side by side, members of different classes that had always kept themselves apart”. The pressures of this group grew, not only against the streetcars, but also against the railroads, which hitherto had been acclaimed as a force of progress for the coffee-based economy. “The situation was even worse when it came to pedestrians, as it was seen as legitimate to use force and violence to get them off the roads so as to free them for traffic”. Thus, the common good was never one of the concerns of the elite, which, the researcher tells us, regarded public space as an extension of private space, taking into account only the desires of a group that encouraged the construction of a complex infrastructure for cars, without creating a counterpart for the groups whose lives had been affected by the new means of transport. By the late 1920’s, vehicles had become the absolute rulers of the streets, while pedestrians were seen as a “hindrance to the possible utopia”, as invaders. The historical past reinforces the current problems. “The automobile, having arrived, became dominant, in line with the model of the Brazilian aristocratic segments. The latter, owning cars, abandoned streetcars and trains, reiterating disdain for public transport and strengthening our hierarchical bias”, analyzes Da Matta. “In Brazil, we resumed the use of litters when we adopted individual transport. This is how we became modern and similar to the Americans, and remained loyal to our preference for a hierarchically constructed space. We went through hoops to adopt cars, but we failed to teach motorists to learn the rules.”

Reproduction from the book Caricaturistas brasileiros 1836-1999This is why, the researcher adds, mandatory stops or waiting for another vehicle or for a pedestrian is seen as a “waste of time”, given that equality is invariably experienced as inferiority in Brazil. “Amongst us, the verb ‘to respect’ denotes choice or option (more so for those who believe themselves to be superior); and the verb ‘to comply’ is compulsory (being applicable to those who see themselves or are regarded as inferior). After all, as the saying goes: ‘Those who can, order; and those with common sense, obey!’ This verb, ‘to respect’, as applied to road signs, people, pedestrians and other vehicles in traffic, reveals the optional side of a society that, to this day, has refused to face equality as a principle of democracy”, says Da Matta. The outcome of this clash between equality and inequality, continues the anthropologist, explains the frequent use of the “save yourself if you can” principle. “Instead of waiting for our turn, we resort to ‘Do you know who you’re talking to?’ and try to get out of the situation ‘no matter how’. Whether by driving up the sidewalk without thinking about the other cars, road signs, crossings and pedestrians, by creating an extra road, or by complaining loudly and arguing uselessly with other motorists who are ahead of us who, in turn, are also shouting and complaining”, he analyzes. “In other words: we voluntarily take over the public space, on our own account and violently, by force, resorting to personal and aggressive actions, disregarding its consequences, whether because we are stressed by the situation that causes us to waste time, or because we are unable to reach our destination”. In this hierarchical struggle, which has ancient roots, the force of the law becomes relative. “The presence of a traffic warden makes the egalitarian attitudes emerge; his absence brings back the notion of ‘more or less’, of degree and of the old hierarchical precedence. It is the perception of the infraction as a standard that is at play, the notion of impunity and also the assurance that certain people are punished while others are not”, he says.

Reproduction from the book Caricaturistas brasileiros 1836-1999This is why, the researcher adds, mandatory stops or waiting for another vehicle or for a pedestrian is seen as a “waste of time”, given that equality is invariably experienced as inferiority in Brazil. “Amongst us, the verb ‘to respect’ denotes choice or option (more so for those who believe themselves to be superior); and the verb ‘to comply’ is compulsory (being applicable to those who see themselves or are regarded as inferior). After all, as the saying goes: ‘Those who can, order; and those with common sense, obey!’ This verb, ‘to respect’, as applied to road signs, people, pedestrians and other vehicles in traffic, reveals the optional side of a society that, to this day, has refused to face equality as a principle of democracy”, says Da Matta. The outcome of this clash between equality and inequality, continues the anthropologist, explains the frequent use of the “save yourself if you can” principle. “Instead of waiting for our turn, we resort to ‘Do you know who you’re talking to?’ and try to get out of the situation ‘no matter how’. Whether by driving up the sidewalk without thinking about the other cars, road signs, crossings and pedestrians, by creating an extra road, or by complaining loudly and arguing uselessly with other motorists who are ahead of us who, in turn, are also shouting and complaining”, he analyzes. “In other words: we voluntarily take over the public space, on our own account and violently, by force, resorting to personal and aggressive actions, disregarding its consequences, whether because we are stressed by the situation that causes us to waste time, or because we are unable to reach our destination”. In this hierarchical struggle, which has ancient roots, the force of the law becomes relative. “The presence of a traffic warden makes the egalitarian attitudes emerge; his absence brings back the notion of ‘more or less’, of degree and of the old hierarchical precedence. It is the perception of the infraction as a standard that is at play, the notion of impunity and also the assurance that certain people are punished while others are not”, he says.

The absence of patience when it comes to somebody else is undeniable, notes the researcher. It is born out of this feeling of superiority, according to which everyone should understand us and respect us, although the opposite is not absolutely true. “If our car breaks down and causes a traffic jam; if we find an old friend driving next to us and chat with him; if we stop at the door of our kids’ school, that’s not a problem, because the others are invisible; we’re not getting in anybody’s way, but just doing something normal (and legitimate). Hence our indignation when somebody honks the horn and calls our attention to the infringement; hence our objections to the ‘rudeness’ of whoever is complaining, who should be understanding and wait, not for his or her turn, but for us”. Still, when we turn into the “other person”, everything changes. “The impatience, the rush, which is the friend of imprudence and the sister of accident, are part of the Brazilian driving style. It betrays the awareness and inability to negotiate politely and bares an incapacity that reveals the lack of manners, of preparedness for equality”, assessed the anthropologist. Another expressive element of this scheme, according to Da Matta, is the strong mental or psychological identification between the motorist and the vehicle. Indeed, this reveals the root of the lack of space in traffic for the circulation of cars that take up a significant area although they are carrying just one person, a supercitizen that is ensconced in his own world. Thus, the car becomes a tool for projecting its owner’s personality, as well as an index of social climbing and consumption capacity: offending the car is tantamount to offending the motorist. “Thus, a slight, involuntary bump or a collision are invariably the starting point of ‘scenes’ and never what they are in reality: an event that happened by chance, an accident. Therefore, the starting point of the drama of any crash is to establish ‘guilt’ with social or physical coercion and the famous ‘Do you know whom you’re speaking to?'”. Precisely what Bilac and Patrocínio would have said back in 1903 if any authority questioned what the car was doing up a tree.

Republish