Most Brazilian federal universities are limited in the way they monitor their communication actions, without knowing how the public receives or interacts with the knowledge disseminated, despite having a significant social media presence. This is one of the conclusions of a study conducted by a group of researchers from the Department of Science and Technology Policy (DPCT) at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) Institute of Geosciences, published in September in the Journal of Science Communication. The research looked at public and science & technology communication produced by 51 of these institutions (73.9% of Brazil’s total) in the digital environment.

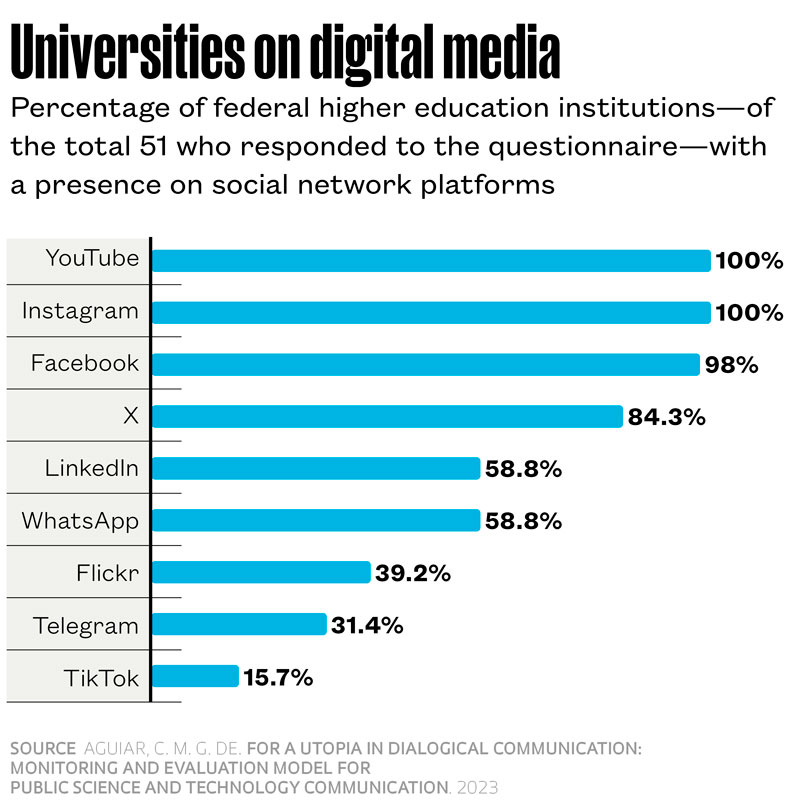

When the data were collected in 2022, all the institutions assessed had profiles on YouTube and Instagram, 98% were on Facebook, 84.3% on X, almost 60% on LinkedIn and WhatsApp, and just eight (15.7%) used TikTok (see graph). The data were obtained based on responses from communication managers to a 32-point questionnaire on their perception of communication conducted by the institutions, along with the indicators adopted and the structure of their teams.

Around 30% of them were not monitoring their communication actions, and of those that did, the majority (55%) were not doing so systematically, regularly, or frequently. Only 17.6% used professional tools enabling more comprehensive analyses than those provided by social network platforms, with just 13.7% stating that they had their own monitoring indicators, with specific aims in line with their communication strategies.

“Monitoring the performance of public communication actions is paramount for understanding how people interact with and respond to content,” observes journalist Cibele Aguiar, lead author of the article based on her doctoral research and defended in March 2023 at DPCT. “The systematic practice of monitoring also brings together important evidence to enable these actions to be improved upon,” she adds. Aguiar is the social media lead at the Federal University of Lavras (UFLA), in Minas Gerais. Some of the data shared in this report are also drawn from her thesis.

Indicators

In one of the research stages, Aguiar selected and validated 26 indicators allowing public university science & technology communication performance to be monitored and measured. The indicators were divided into three types: informational, engagement-based, and participative. The discussion on these metrics was presented in an article in the November 2022 issue of the Journal of Science Communication – Latin America.

The research then evaluated perceptions regarding the use of these indicators of communication managers at several universities, who indicated which of the metrics were already being applied in monitoring the social network profiles of the institutions. The study shows that most of them concentrate their analyses on the informational type, which estimates the dissemination and reach of content published on university actions and research, such as post frequency (78.4% of the total) and increased number of followers (74.5%).

The engagement and participation indicators, which measure effective interaction with the public, are used less than the informational ones. In respect of the engagement indicators, which gauge how much the public interacts with the disclosed content, only 5.8% calculate the percentage of people outside academia making comments, for example.

The majority of participation indicators, which look at involvement of the public in actions undertaken by the institutions, is used by at least 20% of them. For example, these indices monitor the presence and reach of graduate program communication channels in digital environments, or social participation in research projects. “The three types are complementary, and indicate layers that can be reached and combined. They are part of a model that’s still developing,” says Aguiar.

According to 72.5% of universities, most people accessing and engaging with their S & T information have an academic profile

“The data suggest that we have a ways to go to achieve public science & technology communication that is more complex or able to measure its level of dialogue with the public. We are still talking to ourselves,” observes Sérgio Salles-Filho, coordinator of the Laboratory for Studies on the Organization of Research & Innovation (LAB-GEOPI) at UNICAMP, one of the authors of the article and advisor on the thesis. However, he stresses that efforts are ongoing among all universities participating in the study to indicate their research actions and outcomes to a wider public, represented by the significant presence on social media. “It is an important part of responsible evaluation, which seeks to focus on metrics of engagement with society, going beyond the number of publications,” he says.

The data indicate that one of the key communication challenges for federal universities is to burst their bubble and reach more wide-ranging sections of society. According to 72.5% of managers, most of those accessing and engaging in S & T information published on educational institution channels have an academic profile—students, professors, and researchers. Only 11.8% estimate that most people interacting are not academic. The remaining 15.7% claimed not to know the profile of their visiting public.

Another challenge is the reduced number of communication professionals, according to 82.3% of managers. At 62.7% of the sampled universities, there is no professional specifically responsible for S & T communication, and 43.1% have no social media-trained staff, making it difficult to monitor the more qualitative indicators such as engagement and participation.

“Public universities have been attacked in this current climate of disinformation,” highlights Thaiane Moreira de Oliveira, of Fluminense Federal University (UFF), who did not take part in the study. “For this reason, it is important to understand how this communication happens, and circulates, and what needs to be done to improve,” adds the researcher, one of the coordinators of a report on disinformation released in June by the Brazilian Academy of Science (ABC), in which one chapter highlights the need for higher education institutions to bolster their teams and communication actions.

Oliveira stresses that universities have an important role to play in tackling disinformation, due to the credibility they have with the population and being focal points for scientific output in the country. “This was even more evident during the pandemic,” she says. In her view, science communication actions should be coordinated between departments, researchers, and communication sectors at institutions.

To reach a wider public group, the Porto Alegre Federal University of Health Sciences (UFCSPA), which responded to the DPCT questionnaire, redirected its communication actions on social media during the recent climate disaster which led to large-scale flooding in the southern Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul. The institution produced content on exit routes from the city and tutorials on the use of telephone networks and water.

A video made by the university, with the involvement of an in-house infectologist, refuted the supposed efficacy of a prophylaxis for leptospirosis that was circulating on WhatsApp groups, disseminated by a group of physicians, and much sought after among those made homeless by the disaster. “We saw that in certain contexts, such as the climate crisis, shifting the focus of the institution’s actions from the center of communication and working to respond to local social demands brings us closer to other groups. This is important for all to realize that science is in their lives, and to see the university as an arm of the State,” observes Janine Bargas, a researcher and head of communication at UFCSPA.

Representatives from the Federal University of ABC (UFABC) were also interviewed during the study; the institution has had social media profiles since 2013, and retains a specialized company to monitor its actions in the digital environment. One of its strategies is to produce collaborative content created in liaison with other institutions. “We have an extension project in partnership with UFSCar [Federal University of São Carlos], called ClickCiência, in which we post joint content, thereby increasing its range,” says Mariella Mian, coordinator of the UFABC Communication and Press Office. The posts include videos in which university researchers present their work.

This collaborative strategy between institutions has been under discussion in recent months by the College of Federal University Communication Managers (COGECOM), linked to the Brazilian Association of Directors of Federal Higher Education Institutions (ANDIFES). The Association is working to create a scientific dissemination agency set to host research news from the 69 Brazilian federal universities on a single platform. “The aim is to create a unified channel that provides visibility to the output of Brazilian institutions in a balanced way across the five regions,” explains COGECOM coordinator Rose Pinheiro, a professor at the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS). She says that the discussion on monitoring communication campaigns is on the agenda for collegiate meetings. “There is concern over the effectiveness of current measurements, which often focus on the reach and number of followers without considering the real impact of the actions,” she concludes.

The story above was published with the title “The challenge of bursting the academic bubble” in issue 345 of November/2024.

Scientific articles

AGUIAR, C. M. G. de et al. Are we on the right path? Insights from Brazilian universities on monitoring and evaluation of Public Communication of Science and Technology in the digital environment. Journal of Science Communication. Vol. 23, no. 6. Sept. 2024.

AGUIAR, C. M. G. de & SALLES-FILHO, S. L. M. Tipos ideais e Teoria da Mudança: Proposição de modelo de avaliação para a Comunicação Pública de Ciência e Tecnologia. Journal of Science Communication (JCOM) – América Latina. Vol. 5, no. 2. Nov. 2022.

Republish