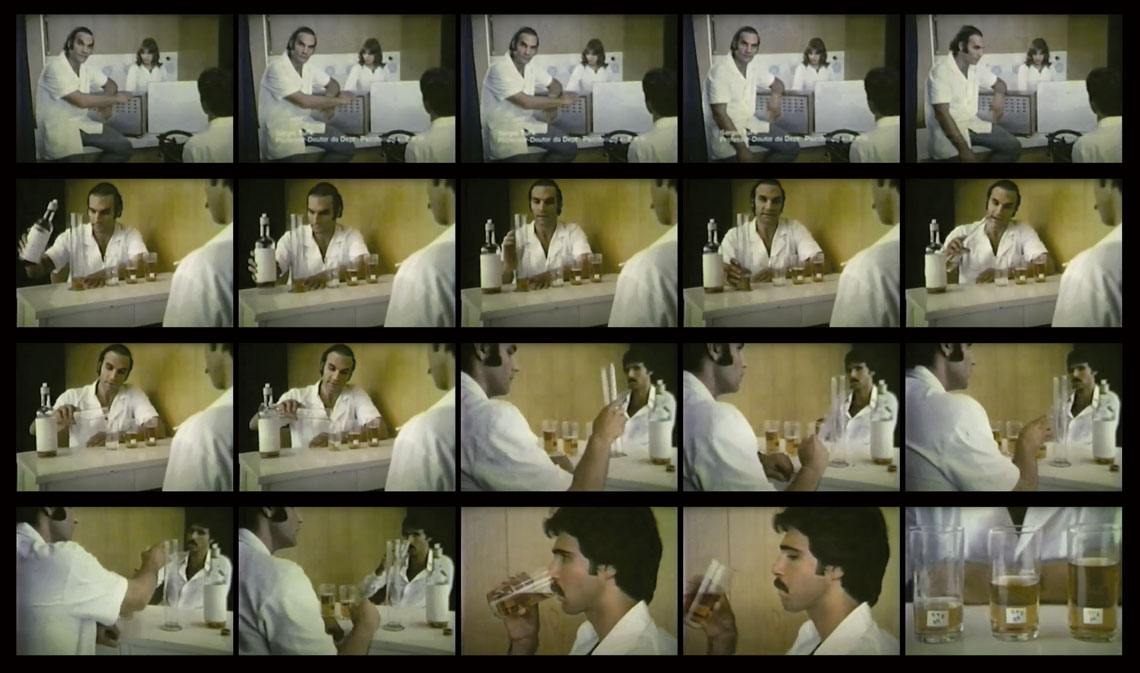

In the 1970s, art theorist and curator Arlindo Machado (1949–2020), one of the pioneers in the field of digital media and arts in Brazil, got involved with studies of the Department of Psychobiology of the São Paulo School of Medicine (EPM), one of the units of the current Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP). While the members of the laboratory led by doctor Sérgio Tufik were concerned about investigating the effects of drinking at the wheel or the impacts of sleep deprivation in mice, Machado sought solutions to record the research subjects with his camera without interfering in the experiments. That is how the films A influência do álcool nas atividades psicomotoras envolvidas no ato de dirigir veículos (The influence of psychomotor activities on the act of driving vehicles; 1978), and Sistemas dopaminérgicos cerebrais (Brain dopaminergic systems; 1979) came about.

To film this last work, for example, Machado used special close-up lenses and produced boxes with one of the glass walls. “I, for my part, made suggestions with regards to adapting the investigative devices for better visualization in terms of light, framing, proximity, capture of natural sounds, etc., but in such a way to not interfere in the behavior of the mice, making us as invisible as possible to them,” wrote Machado, who was a professor at the School of Communications and Arts of the University of São Paulo (ECA-USP) and the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC-SP), in the article “O cinema científico,” (“Scientific cinema”), published in 2014.

Machado’s two productions were shown at the fourth edition of the Festival of Scientific Films (FEFICI), held at the end of 2022, in the Banco do Brasil Cultural Center, in São Paulo, with support from FAPESP. The digitalization of the material was the role of Jane de Almeida, professor of the PUC-SP communication and multimedia course, who located the short films during research to write an article about Machado’s scientific cinema published in 2022. “They are little-known films by Arlindo,” says Almeida. “He was fascinated by scientific cinema and produced reflections on the subject.”

Science New Wave Festival | International Uranium Film Festival / Design N. SuchanekFrom the left, posters for the Imagine Science Film Festival, from 2023, and the 13th edition of the International Uranium Film Festival, planned for 2024Science New Wave Festival | International Uranium Film Festival / Design N. Suchanek

Almeida is one of the creators of FEFICI, together with journalist Alfredo Suppia, professor of the Institute of Arts of the University of Campinas (IA-UNICAMP), and psychologist and communicator Cícero Silva, a teacher on the technology in educational design course at UNIFESP. The three head the Laboratory of Scientific Image (LIC), based in UNICAMP. In its four editions, the festival that first appeared in 2019 has shown Brazilian audiovisual productions made by members of LIC-UNICAMP and undergraduate students. The documentaries cover different fields of science, such as medicine and physics, but the event also opens space for works of science fiction and animation.

In general, the schedule moves between science-dissemination films and scientific films. “Arlindo Machado proposed a distinction between the two categories,” informs historian Rafael Zanatto, who completed his postdoctoral fellowship on the Postgraduate Program in Audiovisual Media and Processes at ECA-USP, with a grant from FAPESP. Among other issues, Zanatto investigated the Festival of Scientific and Educative Cinema, held in 1954, in the city of São Paulo (see sidebar on page 85). “For Machado, science-dissemination cinema has didactic purposes and deals with knowledge that is already discussed and accepted in the scientific community, with the aim of training new generations of researchers.” On the other hand, scientific cinema would be that made within research groups that, in general, are investigating topics still without an answer. In this case, as Machado writes, “generally, the filmmaker is also a scientist or, if not, knows how to integrate their specific knowledge into the objectives being pursued by the group.”

One of the scientific films shown by the FEFICI is Olhos a mil fotogramas (Eyes in a thousand frames; 2022), directed by Almeida and Silva, of LIC-UNICAMP. The short film records refractive laser surgery done to correct ophthalmologic problems such as myopia, astigmatism, and hyperopia. Done using a high-definition camera, the filming was accompanied by the team of ophthalmologist Paulo Schor, of UNIFESP. “In scientific cinema there is a partnership between filmmaker and scientist: they think about the filming process together, in accordance with their expertise,” explains Suppia, from LIC-UNICAMP. “The filmmaker suggests, for example, the most suitable equipment to capture a particular image.”

According to Almeida, the inspiration for creating the FEFICI comes from international initiatives, such as the Pariscience International Film Festival, which arose in 2005, in France, and the Imagine Science Film Festival, created in 2008, in New York City (USA). In relation to the last one, the 2023 edition, held in October, showed 64 productions in the competition from countries such as Denmark, Canada, and the Philippines. Brazil was represented by two documentaries, both from 2023. One of them is Holding up the Sky, an ethnographical film by Pieter Van Eecke, a Belgian director based in South America, starring Davi Kopenawa, leader of the Yanomami. The other is a feature-length film, Rejeito (which translates as tailings in English), by Brazilian director Pedro de Filippis, which denounces the environmental damage caused by the breach of the dams containing tailings from mining in Minas Gerais.

Parceiros da Floresta / Promotional material A scene from the documentary Parceiros da Floresta (Forest partners), by Fred Mauro, shown in 2023 in the Science Film FestivalParceiros da Floresta / Promotional material

With the fifth edition planned for May 2024, FEFICI is one of the few festivals of its type in activity in the country. “It is important that they exist to give visibility to this type of film and, therefore, encourage the production of this content in Brazil,” defends Almeida. Along the same lines, sociologist Márcia Gomes de Oliveira, from Rio de Janeiro, has been promoting the International Uranium Film Festival (IUFF) since 2011, in partnership with Norbert Suchanek, a German journalist, documentary maker, and chemical engineer who lives in Brazil. The festival unites documentaries and fictional works with a specific theme, as the title of the event suggests. “Our focus is discussing nuclear energy and its risks,” says Oliveira, a professor at the Support Foundation to the Rio de Janeiro State Technical School (FAETEC). “Every year, we receive lots of films from Europe, Asia, Oceania, and North America, but there is still little production in Brazil and the rest of Latin America.”

The 12th edition of IUFF, held in May 2023, in the Film Library of the Museum of Modern Art (MAM) of Rio de Janeiro, presented 17 independent audiovisual productions, such as the documentary Downwind (USA, 2023), which heard activists and residents of a nuclear test area in Nevada, USA. Only two films had a link with Brazil. The first is Devil’s work (2015), fiction based on real facts directed by filmmaker Miguel Silveira, born in Rio de Janeiro but who has settled in the USA. The story follows an adolescent whose father, a soldier in the US army, dies after being contaminated by depleted uranium in the Gulf War (1990–1991). The other one, Segurança nuclear (Nuclear safety; 2019), is a short documentary by Suchanek that deals with the danger of radioactive waste from episodes such as the cesium-137 accident that occurred in Goiânia (state of Goiás), in the 1980s.

The first edition of the festival, in 2011, was held in Rio de Janeiro. Since then, the event has traveled to places such as Germany, Jordan, the USA, Canada, and Portugal. During the COVID-19 pandemic, between 2020 and 2022, it gained an online version. According to the organizers, the films are produced by untrained filmmakers or those with scientific training and occasionally by scientists. A commission composed of researchers, such as radiobiologist Alphonse Kelecom, of the Department of General Biology of Fluminense Federal University (UFF), assesses the content of all the entries.

Another example of a festival focused on the dissemination of scientific content is the Science Film Festival (SFF). The event premiered in Bangkok, Thailand, an initiative of the local Goethe Institute, and spread to other countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. It has been held in Brazil since 2019, in partnership with Midiativa, a nongovernmental organization (NGO) based in São Paulo. The fifth Brazil edition had the theme of sustainability, and between October and December 2023, showcased 48 audiovisual productions, including films and television programs, from 21 countries. In addition to access to online content, there were in-person events and exhibitions in the capital of the state of São Paulo. “In the curation we seek to include fun and inspiring productions to spark the curiosity of children and adolescents, which are our target audience along with teachers from basic education,” says Thaísa Oliveira, general coordinator of the SFF in the country. For Beth Carmona, director of Midiativa, audiovisual language has a lot to do for science. “But public and private incentives are necessary for this to happen,” she adds.

The event showed films from 17 countries and generated discussions about this type of production

Cheval MarinImages of the film O cavalo marinho (1934), by French filmmaker Jean PainlevéCheval Marin

The first film festivals aimed at the dissemination of science appeared in Europe, at the end of the first half of the twentieth century, affirms historian Rafael Zanotto. One of the references in this field, he says, was Frenchman Jean Painlevé (1902–1989), who in the 1940s and 1950s presided over the International Association of Scientific Cinema (AICC), created in 1947, in France, and based in Brussels, in Belgium. A graduate in math, medicine, and natural sciences, Painlevé also dedicated himself to recording moving images of animal life that led to films such as The Sea Horse (1934). In order to not damage the camera during filming, the photographer and filmmaker created a waterproof box to house the equipment.

In 1954, Painlevé came to Brazil to celebrate the Festival of Scientific and Educational Cinema, held between February 15 and 25, in the Museum of Modern Art (MAM) in São Paulo. With support from the AICC, the festival was coordinated by cardiologist Pedro Gouveia Filho, president of the National Institute of Educational Cinema (INCE) (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 271), and by reporter and photographer Benedito Junqueira Duarte (1910–1995), who recorded over 500 films in the field of medicine from the 1940s onwards and became a reference in Brazilian scientific cinema (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 288) The event is part of the I International Cinema Festival of Brazil, held as part of the commemorations for the IV Centenary of São Paulo.

According to the historian, who wrote an article about the Scientific and Educational Cinema Festival during his postdoctoral fellowship at ECA-USP, the schedule presented Brazilian and foreign scientific documentaries and science-dissemination films. The selection included titles such as Miocárdio em cultura (Myocardium in culture; 1942), directed by filmmaker Humberto Mauro (1987–1983), with collaboration from biochemist Carlos Chagas Filho (1910–2000), from the University of Brazil, the current Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). “By gathering films from 17 countries, the festival showed the Brazilian public what was being done in the world in terms of the production of scientific content and also generated discussions about the nature of this type of cinema,” says Zanatto. “The initiative did not continue, although other festivals of the same kind were held in the country from the 1960s onwards,” he concludes.

Project

The French and German contribution to the formation of cinema history (1945-1952): Criteria, theories and perspectives (nº 19/13106-8); Grant Mechanism Bolsa de Pós-doutorado; Principal Investigator Eduardo Victorio Morettin (USP); Beneficiary Rafael Morato Zanatto; Investment R$ 382.195,51.

Scientific articles

MACHADO, A. O cinema científico. Revista de Cultura Audiovisual. dec. 2014.

ZANATTO, R. M. O festival de cinema científico e educativo (1954): Jean Painlevé, Ince, B. J. Duarte. Revista Brasileira de Estudos de Cinema Audiovisual. jul. 2021.

ALMEIDA, J. et al. Passages on Brazilian scientific cinema. Public Understanding of Science. 19 dec. 2016.

ALMEIDA, J. Apontamentos sobre o cinema científico: Arlindo Machado. Significação Revista de Cultura Audiovisual. feb. 2022.