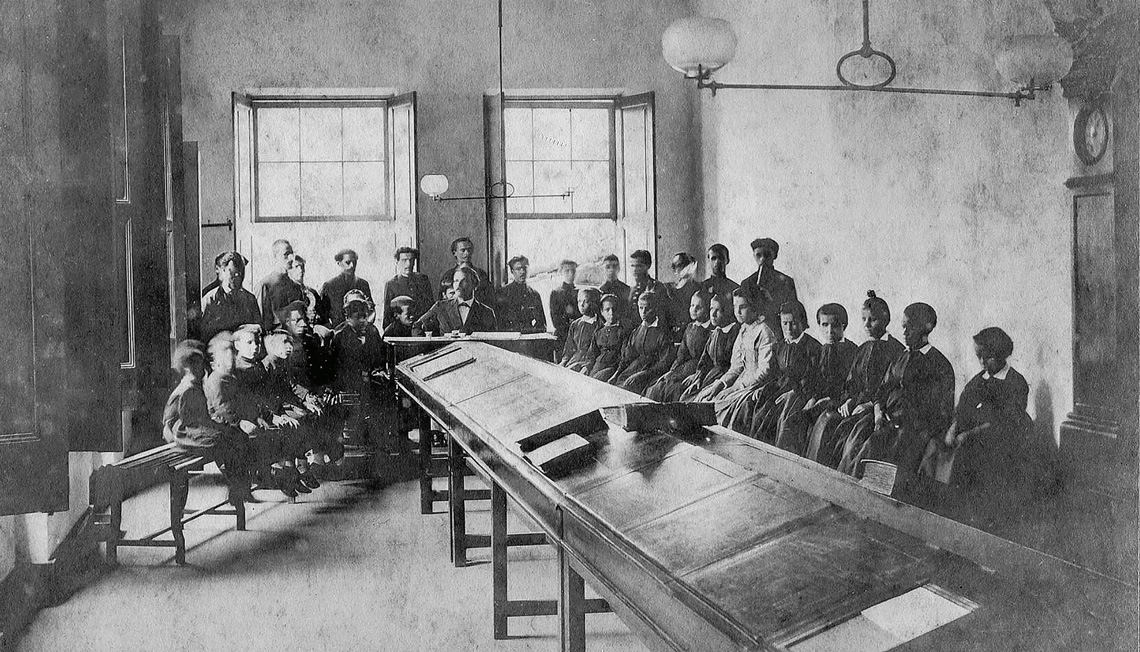

For three years, the teachers at Brazil’s Imperial Institute for Blind Children, inaugurated on September 17, 1854, on the hill of Saúde in central Rio de Janeiro, used only imported books in Portuguese and French to teach visually impaired children to read. Their own print shop, the first in Brazil to print in braille, began to take shape two years later. This was thanks to a donation of 500 metal types (characters), cast in molds from Paris, by one of the institute’s students and his brother, who owned a printing shop. The donation encouraged Dr. Claudio Luiz da Costa (1798–1869), the school’s second director, to apply greater pressure on the government, submitting reports that emphasized the “urgent need for a printing press.”

The print shop began operating in 1857. However, it was described as a “poorly assembled” workshop, with “few, if any, materials necessary for printing work” and an “old, very small, and heavy” press. These complaints were sent to government authorities by the engineer, military officer, and politician Benjamin Constant Botelho de Magalhães (1836–1891), who was the school’s director from 1869 to 1889. In his honor, the institute was renamed in 1891 to Benjamin Constant (IBC) and moved to its current headquarters, an imperial building on Praia Vermelha, while remaining a public institution now linked to the Ministry of Education.

In the early years, students assisted master printer Manoel Ferreira das Neves in printing the books. They would adjust the pieces on the press, fit the sheets of paper into the tray, and push the levers to press the characters into the paper, creating the raised dots. Once finished, the pages had to be taken outside immediately, as they would deteriorate if left in the hot and humid room.

In 1859, the printing house produced 60 copies of Método para tocar órgão harmônico (A method for playing the harmonic organ), 10 of Diversas obras para leituras d’instrução e recreio (Various works for educational and recreational reading), and 16 music booklets, comprising methods for teaching counterpoint and playing the harmonic organ, poetry, catechisms, fables, and geography lessons. From 1869 to 1872, 360 books were printed, mostly focusing on French and Portuguese grammar.

National Archive / Wikimedia CommonsBenjamin Constant, director and promoter of the institute named after himNational Archive / Wikimedia Commons

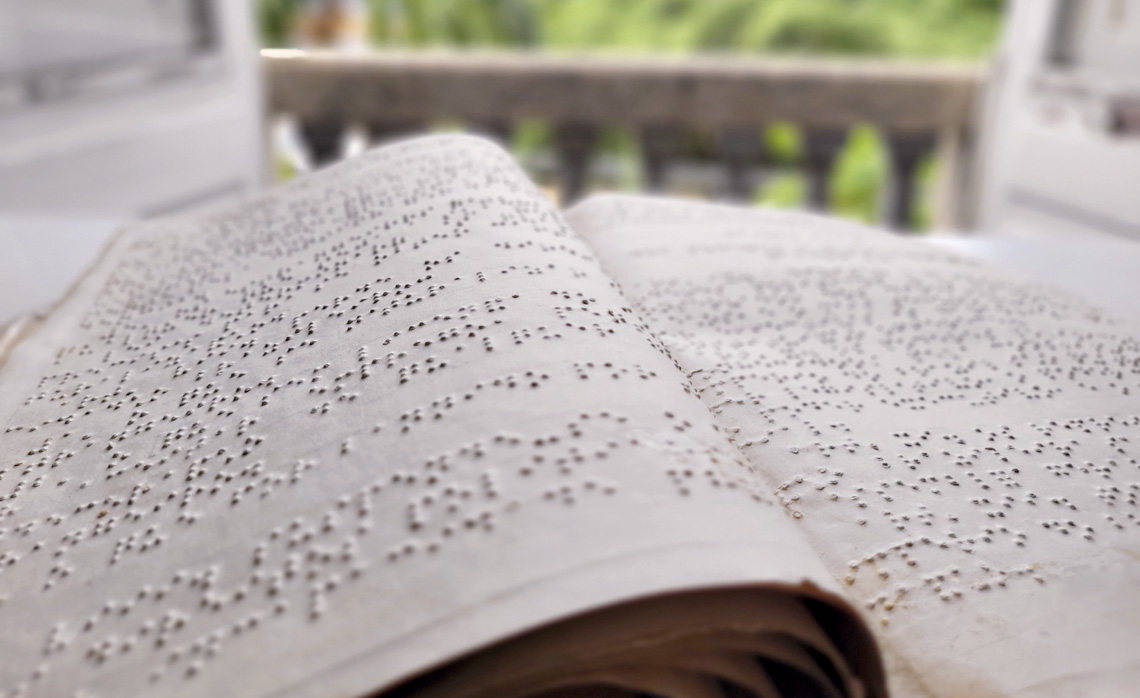

Since printing was slow, books were also produced directly in the classroom. The teachers would dictate the chosen works, and the students would transcribe the words into braille. “The students used a puncture, a kind of tip, to write and mark the braille on the paper, and a ruler, today known as a reglete, to ensure the correct positioning of the characters marked with the puncture,” says historian and IBC professor Gabriel Bertozzi Leão, who completed his doctorate in 2023 at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) on the first braille books in Brazil. Even so, the quantity was insufficient. “Until the Republic, the institute couldn’t print enough books to serve its own students.”

The institute was the brainchild of French-Brazilian doctor José Francisco Xavier Sigaud (1796–1856) and José Álvares de Azevedo (1834–1854), the first blind teacher in Brazil, who had taught Sigaud’s daughter, Adèle Marie Louise (1840–?). Azevedo studied at the National Institute for Blind Youth in Paris and returned to Rio in December 1850 with the intention of opening a similar school.

“Many schools for the blind in nineteenth-century Europe used relief writing methods based on the linear Roman alphabet, and some developed their own relief codes,” notes Leão. “Gradually, throughout the nineteenth century, braille became recognized worldwide as the best system of reading and writing in relief for the blind.”

The braille system was developed after the relief system, when Louis Braille (1809–1852), who had lost sight in both eyes as a child, was studying at the Paris Institute. In 1821, he learned about the communication code created by French army officer Nicholas-Charles Barbier de la Serre (1767–1841). Known as night writing, this system consisted of a sequence of 12 dots and raised strokes used to transmit coded messages in the dark to sentries.

Braille simplified the code from 12 to 6 dots and added numbers, punctuation marks, and musical notations. In 1829, he published a book outlining the method, in which each letter is represented by a combination of one to six dots arranged in two columns of three dots each. The letter A is a single dot, the first in the left-hand column, while P consists of four dots: three in the first column and one in the second.

Gabriel Leão / IBCThe braille version of the Imperial Constitution of Brazil, printed in 1878Gabriel Leão / IBC

Braille’s blind friend and mechanic Pierre-François-Victor Foucault (1797–1871) developed the first known typewriter, which printed Roman characters in relief and allowed blind people to communicate with sighted individuals. Called a raphigraph, it consisted of a plate, a frame to hold the paper, and 10 pistons—five for each hand. It was one of the precursors to the print typewriter and was used for about 50 years until it was replaced by machines invented in Germany and the United States.

Marveling at his daughter’s progress, Sigaud used his connections as a court physician to secure an audience for Azevedo with Dom Pedro II (1825–1891). When the emperor saw that a blind person could read and write using the braille system, he approved the creation of a similar institution in Brazil as the one in Paris. In his 1862 book História cronológica do Instituto Imperial dos Meninos Cegos (Chronological history of the Imperial Institute for Blind Children), Costa recounts that the Minister for the Affairs of the Empire, Luiz Pedreira do Couto Ferraz (1818–1886), was quick to act: “He ordered alphabets in raised dots from Paris, books printed in Portuguese in the same manner, and all the necessary materials to begin private instruction for the blind.”

The Brazilian institute shared similarities with the French one, such as its organizational structure and the educational and vocational lessons it offered, but there were also key differences. “The French institute had a strong vocational education program, with several vocational workshops, while the Brazilian institute, during the Empire, had only two: a printing and a bookbinding workshop. It also had no intention of providing comprehensive care for the large portion of the Brazilian population with visual impairments or contributing to their autonomy,” says Leão. “It was more of a showcase, intended to demonstrate to the population and foreign nations the Empire’s supposed achievement of values related to civility and modernity.”

While the Paris school catered to 400 to 500 students, the Rio school was limited to just 30 for a long time. Boys and girls aged 6 to 14 were accepted, as long as they were free and had total, incurable blindness. The school offered primary education, moral and religious education, music instruction, some branches of secondary education, and factory trades. A chaplain oversaw religious instruction.

Dorina Nowill Foundation For the Blind ArchiveProduction of braille books in 1949 at what was then known as the Blind Book Foundation in BrazilDorina Nowill Foundation For the Blind Archive

“Through the teaching of catechism and the gospel, social and moral customs were transmitted to the students,” comments Bárbara Santos, a graduate in letters and a teacher at IBC, in an article published in September 2019 in the journal Philologus. According to her, the teaching had “a nationalist character, but also a liberating one, in the sense of providing some independence for those who had no expectations for the future, given that the survival of the blind at that time depended on the goodwill of family members or the charity of society.”

Professor Cássia Geciauskas Sofiato, from the School of Education at the University of São Paulo (FE-USP), after reviewing documents from 1854 to 1889, concluded that the institute was part of the hygiene movement, which emphasized concerns with urban architecture and daily habits to prevent the spread of infectious diseases. Students were only admitted after a medical examination confirming that they had received the smallpox vaccine—a requirement for them, unlike the general population—and that they were not suffering from any contagious disease. In an article published in July 2024 in the journal Educação Especial (Special Education), she states that until the institute moved to its current headquarters in 1891, it occupied unhealthy spaces: “A number of deaths were reported due to illness, and maintaining health, controlling diets, and caring for the sick were Herculean tasks given the conditions at the institution.”

During the Republic, the institute expanded rapidly, especially after Benjamin Constant became Minister of Public Instruction in the provisional government. In addition to facilitating the relocation of the headquarters to Urca, in the southern part of the city, he helped the board increase the student population to over 100 and established workshops for producing brushes, brooms, mattresses, cushions, and chairs.

Today, the IBC serves 991 people of all ages. Book printing, one of its core activities, begins with the selection of titles, which is managed by a team led by Hylea de Camargo Vale Assis, a Portuguese teacher and supervisor of the Braille Press Division. “We receive requests from public institutions all over Brazil, but the most frequent requests come from primary schools,” she says.

Hotdamnslap / WikipediaThe raphigraph, the first typewriter for the blind, was invented in 1841 by François FoucaultHotdamnslap / Wikipedia

The selected book is sent in PDF format to the adapters, who then transform the text into braille code. “We mainly adapt figures, graphs, and other visual elements,” says math teacher and adaptation coordinator Luigi Amorim. “When necessary, we also modify some words, such as ‘highlight this word,’ in textbook exercises, because they involve visual cues that are difficult for blind individuals to work with.”

In the next stage, transcribers carefully assemble the digital file into braille text, which will then be reviewed by blind proofreaders. If any errors are found, the sheets are returned to the adapters, and only once they are perfect do they go to one of the printers—one on the first floor, at the back of the building, for large print runs, and a smaller one on the second floor, equipped with modern printers, for smaller print runs.

Each year, the editorial team transcribes around 200 titles and prints more than 60,000 copies of textbooks and magazines, which are sent to schools that serve visually impaired individuals. According to Assis, since its inception, the institute has printed over 4 million pages in braille.

In October, IBC opened registration for the first edition of the Braille Book Club, which will bring members together remotely every quarter to read and discuss braille books. With 315 members already signed up, the first meeting is expected to take place early this year. “There is a lot of demand for books among the blind,” says Assis. “After leaving school, many lose access to books. We aim to fulfill this reading desire by offering the book from the conversation circle and another from our catalog.” The first book to be discussed will be Ponciá Vicêncio by Conceição Evaristo.

Enrico Di Gregorio | Dorina Nowill Foundation For the blind archiveIn operation: large print presses at IBC (left) and digital presses at the Dorina Nowill Foundation (right)Enrico Di Gregorio | Dorina Nowill Foundation For the blind archive

Another printing house

Similar institutes began to emerge in the twentieth century—in Recife in 1909, in Minas Gerais in 1926, and in São Paulo in 1927. The IBC was the only institution producing books for the blind until 1946, when the Blind Book Foundation in Brazil, later known as the Dorina Nowill Foundation for the Blind in 1991, began operations in São Paulo. After establishing the foundation, educator Dorina de Gouvêa Nowill (1919–2010), who became blind at 17 due to an eye infection, led the National Campaign for Blind Education. This was Brazil’s first national organization for people with this type of disability, and it launched programs to provide services for visually impaired people across the country and to prevent blindness.

The foundation produces books in various formats. “Textbooks and literary books made in both braille and ink allow people with and without sight to read simultaneously,” says marketing graduate Carla de Maria, the foundation’s Accessibility Solutions Manager. Another format is audiobooks: “In the past, they were created by artists and volunteers who narrated and recorded literary books, magazines, and other materials. Today, production is much more professional, done in studios,” she adds. In 2023, the foundation launched the Dorinateca online library, which provides free access to 5,559 titles in braille and audio.

In Paço do Lumiar, Maranhão, educator Andriel dos Santos Rodrigues coordinated a study listing 23 technological aids for literacy—such as screen readers, which convert text into audio, voice recognition software, and tactile scanners, which convert images and texts into tactile formats. This study was published in the September 2024 issue of the Ibero-American Journal of Humanities, Sciences, and Education. Rodrigues and his coauthors emphasize that despite advancements, “prejudice, inadequate teacher training, and the shortage of accessible teaching materials” continue to make literacy more difficult for people with visual impairments. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), 506,000 people in Brazil are blind, and 6 million have low vision.

Several initiatives have led to the publication of new materials for this population. In 1985, the National Book Publishers Union and the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office established the Accessible Book Portal, through which blind people can suggest specific titles to publishers. In 2015, Brazil signed the Marrakech Treaty, an international agreement aimed at improving access to books in accessible formats without violating copyright.

The story above was published with the title “Relief writing printing houses” in issue in issue 348 of february/2025.

Scientific articles

FERREIRA, P. F. Recorte histórico: Do Imperial Instituto dos Meninos Cegos ao Instituto Benjamin Constant. Benjamin Constant. Mar. 27, 2017.

RODRIGUES, A. dos S. et al. O uso de tecnologia assistiva no processo de alfabetização do deficiente visual: Em busca de um processo de ensino e aprendizagem inclusivo e significativo. Revista Ibero-americana de Humanidades, Ciências e Educação. Vol. 10, no. 9, pp. 3786–800. Sept. 30, 2024.

SANTOS, B. P. dos. Relatório de 1858 do Imperial Instituto dos Meninos Cegos: Uma análise pela historiografia linguística. Philologus. Vol. 25, no. 75. Sept.–Dec. 2019.

SOFIATO, C. G. Pressupostos higienistas e o Imperial Instituto dos Meninos Cegos. Revista Educação Especial. Vol. 37, no. 1. July 5, 2024.

Book

GUADET, J. O Instituto dos Meninos Cegos de Paris: Sua historia, e seu methodo de ensino. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia de F. de Paula Brito, 1851.