A defense mechanism that has emerged and disappeared several times over the evolutionary history of different lines of plants, particularly trees in hot environments, involves the number of clouds in the sky and plays a crucial role in Amazonia as one of the most important land climate parameters. Most likely developed as a way of dealing with thermal stress peaks, tree foliage emits a volatile compound—isoprene gas (C₅H₈). Under daylight sun, isoprene degrades rapidly after being released, but under certain nocturnal conditions, the compound remains in the air for longer periods, increasing in altitude and transforming into an essential component of atmospheric chemistry: a type of diffuser of the processes that result in clouds. This is the primary conclusion of two new studies conducted by international groups with the participation of Brazilians published simultaneously in the journal Nature in December.

A molecule of the terpene family, which comprises the primary volatile compounds emitted by plants, isoprene reacts with other gases when released by tree foliage, escaping a premature end and causing a series of reactions in the lower and higher troposphere, the most superficial layer of the Earth’s atmosphere. These interactions multiply the rate of aerosol particle formation by more than tenfold, resulting in condensation nuclei, the “embryo” of clouds. This mechanism not only increases the generation of clouds over Amazonia but also over the Atlantic Ocean as well as other parts of the planet. Approximately two-thirds of the Earth’s surface has permanent cloud coverage, a climate aspect that can both heat and cool a region while also resulting in moisture through rainfall.

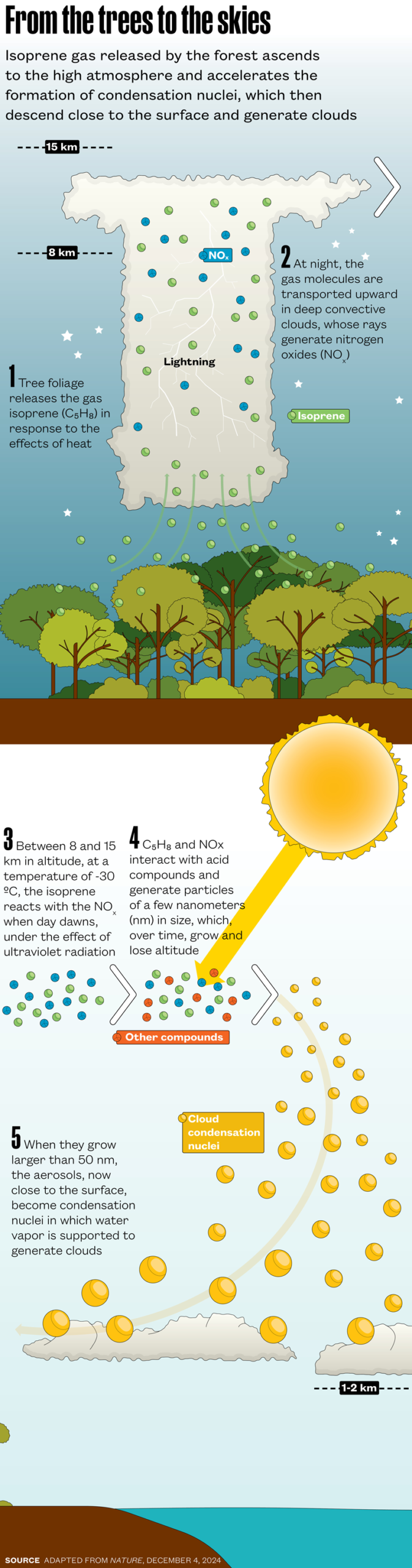

The articles provide a detailed look at the sequence of physical‒chemical interactions between isoprene and other compounds that lead to the formation of enormous quantities of aerosol particles in the high Amazonian troposphere at altitudes between 8 and 15 km (km). These particles initially measure a few nanometers (nm) in diameter, clustering with other aerosols and growing in size over time. They can be transported to different parts of the globe by atmospheric circulation and play important roles in the origin of cloud condensation nuclei. When they reach the lower troposphere, which is between 1 and 2 km in altitude, nuclei that are at least 50 nm in diameter function as water vapor supports, which condense (become liquid) and generate clouds. Without these nuclei, there are no clouds, which can be both fair weather and rainfall.

The discovery of these interactions initiated by the emission of isoprene, which becomes a gas at temperatures in excess of 34 degrees Celsius (°C), explains a phenomenon observed for two decades in the Amazonian skies. At the early 2000s, researchers became aware of the existence of aerosol concentrations in the high tropical forest troposphere that were 160 times greater than those measured close to the surface. However, there was no consistent explanation for these findings until the new studies were published. “We have now solved this mystery and have demonstrated that an organic compound released by the forest—isoprene—initiates the formation process of these aerosols,” says physicist Paulo Artaxo of the University of São Paulo’s Institute of Physics (IF-USP), coauthor of one of the studies, both referenced on the cover of Nature. “It’s very important for us to understand the cloud formation process to improve our weather and climate forecast models.”

One of the articles is based on chemical process data obtained from overflights in Amazonia via the Halo aircraft of the German Aerospace Center (DLR) between December 2022 and January 2023, part of the Chemistry of the Atmosphere: Field Experiment in Brazil (CAFE-BRAZIL) project, a field study conducted two years ago. “We overflew for 136 hours and clocked up 89,000 km over Amazonia,” says meteorologist Luiz Augusto Machado of IF-USP, a collaborator at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Germany, who supervised all the flights and crewed on some. The Halo aircraft took off from Manaus, the Amazonas state capital, before sunrise to capture the physical‒chemical interactions of isoprene without the influence of sunlight, with a continuous range of 10 hours to record atmospheric parameters.

The second study was conducted at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) in Switzerland, using the CLOUD (Cosmics Leaving Outdoor Droplets) chamber. This device reproduces atmospheric conditions and processes. “CLOUD is a 3 m-high stainless-steel cylinder supplied with ultraclean air in the same proportions of nitrogen and oxygen that we have in the atmosphere,” explains Brazilian meteorologist Gabriela Unfer, currently undertaking her PhD at the Leibniz Institute for Tropospheric Research in Leipzig, Germany, and the only Brazilian authoring the articles on high-altitude aerosols.

To enable the CLOUD system to simulate atmospheric conditions in a certain region of the planet, area-specific meteorological and chemical information needs to be input. “The field data obtained during flights in the CAFE-BRAZIL program formed the basis for the correct configurations of temperature, moisture, and gas concentration to be simulated by CLOUD. This is how we reproduced, in the laboratory, the formation of high-altitude aerosols brought about by plant isoprene emissions,” explains Unfer.

The most surprising aspect of the studies is that the aerosols formed between 8 and 15 km in altitude are due to processes that commence among the trees of Amazonia. “If the tropical forest continues to be stripped, this will have an impact on the aerosol production process in the high troposphere, and consequently on the formation of clouds closer to the surface,” says Micael Amore Cecchini of the Institute of Astronomy, Geophysics, and Atmospheric Sciences at the University of São Paulo (IAG-USP), another author of one of the papers, who participated in the CAFE-BRAZIL campaign.

Dirk Dienhart/Max Planck Institute for Chemistry A Halo aircraft overflies Amazonia to obtain atmospheric chemistry measurementsDirk Dienhart/Max Planck Institute for Chemistry

The key to the entire process is isoprene, a volatile, colorless organic compound with a very slight aroma that may be referred to as rubber or petroleum. The release of this gaseous molecule, expelled as a type of vegetation transpiration, is an evolutionary mechanism that helps plants, particularly those in the tropics, protect themselves from the negative effects of heat peaks. Close to the surface, in the low atmosphere, isoprene can last for minutes or a few hours. During sunlight hours, it reacts with ozone and other compounds and quickly disappears, almost completely, from the atmosphere.

However, isoprene molecules are not destroyed, and those emitted after sundown by Amazonian trees escape this premature end and are transported into the high atmosphere by the action of night storms. At approximately 15 km in altitude, where the temperature is lower than -30 °C, isoprene does not degrade as it does close to the surface, and it interacts with other compounds. Nighttime storm rays cause isoprene to bond to nitrogen oxide molecules, quickly forming an enormous number of aerosol particles a few nanometers in size. “In the high atmosphere, isoprene accelerates the speed of aerosol formation by 100 times,” comments Machado. The speed of aerosol movement in the high troposphere can reach 150 km per hour. It is therefore reasonable to suggest that aerosols migrate to regions very distant from Amazonia, where they lose altitude and bond until they form cloud condensation nuclei between 1 and 2 km above the Earth’s surface.

It is likely that this aerosol formation mechanism at high altitudes also occurs in other regions of the globe, especially over the tropical forests of the Congo, Africa, and southeastern Asia. Isoprene is the primary volatile compound emitted by vegetation. Approximately 600 million tons are released into the atmosphere every year. “This type of aerosol particle formation in the high troposphere probably happens not only in Amazonia, but in all tropical forests, given that they all emit large amounts of isoprene,” meteorologist Joachim Curtius of the University of Frankfurt, lead author of the study on data from the CAFE-BRAZIL experiment, said in an interview for Pesquisa FAPESP. “The Amazon forest alone is responsible for more than a quarter of total isoprene emissions.”

The next step in the research will elucidate how the growth and transportation of aerosols occur in the high Amazonian troposphere and how they descend close to the Earth’s surface. “We don’t know how many of these particles are lost by collisions with other particles, and in other interactions, nor how they ‘survive’ and become condensation nuclei in the low altitudes of the tropics, where clouds form,” says Curtius. In this process, isoprene is just the tip of the iceberg—or rather, the cloud.

Projects

1. Interactions between trace gases, aerosols, and clouds in the Amazon: From bioaerosol emissions to large-scale impacts (nº 23/04358-9); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Principal Investigator Paulo Artaxo; Investment R$4,109,920.65.

2. Correlating the organization level of convective cloud fields with hydrological and aerosol cycles in the Amazon (Cloudorg) (nº 22/13257-9); Grant Mechanism Research Grant – Young Investigator Award Program FAPESP Research on Global Climate Change (PFPMCG); Agreement Serrapilheira Institute; Principal Investigator Micael Amore Cecchini (USP); Investment R$1,471,125.05.

3. Interactions between aerosols and weather events in the Amazon (nº 21/03547-7); Grant Mechanism Master’s Fellowship; Supervisor Luiz Augusto Toledo Machado (USP); Beneficiary Gabriela Unfer; Investment R$73,911.67.

Scientific articles

CURTIUS, J. et al. Isoprene nitrates drive new particle formation in Amazon’s upper troposphere. Nature. dec. 4, 2024.

SHEN, J. et al. New particle formation from isoprene under upper-tropospheric conditions. Nature. dec. 4, 2024.

Republish