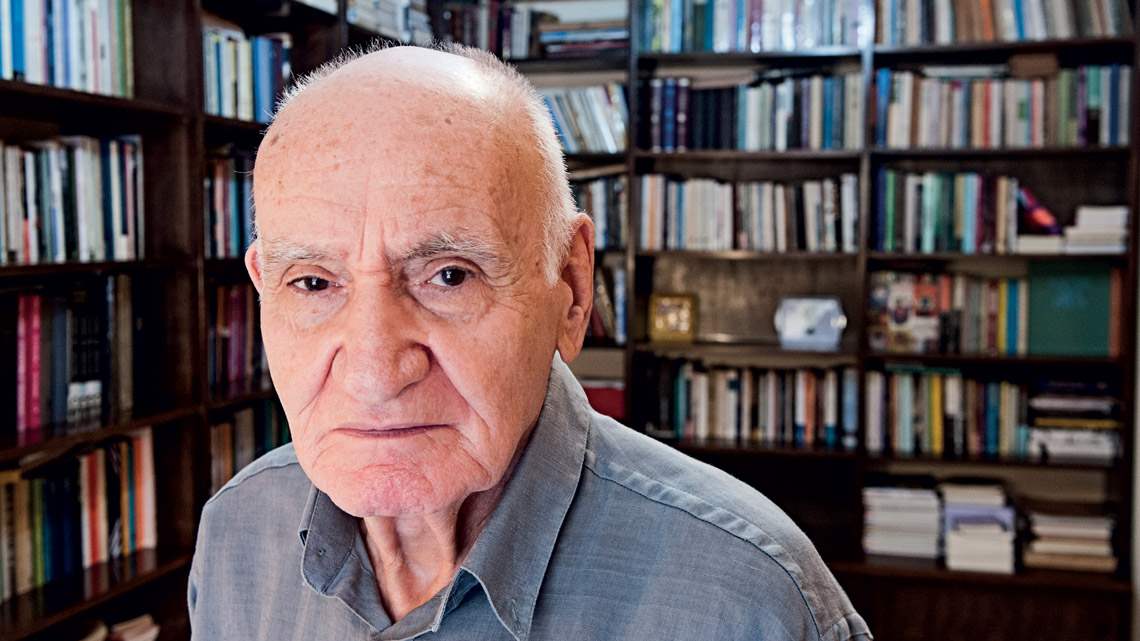

In the history of the Brazilian social sciences, Gabriel Cohn can be considered a pioneer twice over. In the early 1970s, he initiated the first sociological research on communication in the country. Almost two decades later, when he moved into political science, he dedicated himself to normative political theory, with research focused on the theory of justice. In addition to teaching at the School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences at the University of São Paulo (FFLCH-USP), where he became a tenured professor in 1985 and became department chair in 2006, his career includes terms as president of the Association of Sociologists of the State of São Paulo, of the Brazilian Society of Sociology, and the National Association for Graduate Studies and Research in Social Sciences (ANPOCS).

In 2011, three years after retiring, Cohn was recognized once again, in a double dose: he was awarded the titles of professor emeritus at FFLCH and researcher emeritus at the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). And finally, in 2018 he received the ANPOCS Award for Academic Excellence in Sociology. Both prior to and after the ANPOCS award, he has been honored in works such as A ousadia crítica: Ensaios para Gabriel Cohn (Critical Daring: Essays for Gabriel Cohn; Azougue publishing), edited by Leopoldo Waizbort from the Department of Sociology at FFLCH, and Leituras críticas sobre Gabriel Cohn (Critical Readings on Gabriel Cohn), edited by Leonardo Avritzer of the Department of Political Science at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), in the collection Intelectuais do Brasil, from UFMG/Perseu Abramo.

Cohn has his own unique sense of humor, and likes to joke that, like the character Castelo from the short story O homem que sabia javanês (The man who spoke Javanese), by Lima Barreto (1881–1922), on two occasions he ended up receiving attention for knowing things that were unusual among his colleagues at the time. First, his mastery of the German language, which allowed him to focus his studies on Max Weber (1864–1920) and the work of Theodor W. Adorno (1903–1969), and secondly, his research into the mass media.

In this interview, conducted over video, Cohn spoke about how his professional career was marked by a childhood episode, about the influence of Weber and Adorno, two important intellectuals whose work he played a key role in bringing into the Brazilian social sciences, and the challenges that the current political climate pose for social scientists.

Field of expertise

Classical and contemporary sociological theory, classical and contemporary political theory, social theory

Institution

University of São Paulo (USP)

Educational background

Bachelor’s (1964) and master’s (1967) in social science and a PhD in sociology from the University of São Paulo (1971)

Published works

Three books, four collections featuring a variety of authors and themes, three collections of his own articles, 45 articles and book chapters

You’re the second child in a family of Jewish refugees who arrived in Brazil from Germany in 1936. What was your childhood like?

My parents settled in the state of São Paulo during World War II. They arrived here with a 2-year-old baby, my only brother. Right away they got a scare. After leaving everything behind and crossing the ocean in a third-class cabin, heading into the unknown, the first thing they saw upon entering the port of Rio de Janeiro—which for them had meant hope and freedom—was a flag waving the Nazi swastika. It belonged to the company Hamburg Süd. It was a tremendous shock, which contrasted with what they felt later as they walked through the city streets and experienced something unthinkable in Germany, the affection of people cooing at their little boy and trying to communicate with them in a caring way. They had never seen people with black skin, and it was especially among these people that they received the warmest smiles. I was born two years later, and I would say that the principal characteristic of childhood during that period, for those who weren’t in an urban center, was isolation. I was raised in an environment of severe hardship, although I didn’t feel anything was that bad as a child.

So you were educated out in the country?

My parents only had high school educations. But the German high schools at the beginning of the last century were places that probably went beyond what our high schools offer today. My parents held knowledge in very high regard. But my school education was completely chaotic. It started at what was then called a mixed rural school. “Mixed,” because the students from the first three years were taught in the same room and the teacher, a virtuoso, had to make an enormous effort to keep three classes in order. One fine day someone acted up, and the teacher said: “Today nobody gets to go to recess.” That astonished me. As I left class—I don’t know where I got the courage—I asked her, “If only one person did something wrong, why was everyone punished?” Her answer was, “The innocent pay for the sinners.” That hit me like a bolt of lightning. I was 7 years old and I could never forget it.

To what extent did this incident affect your life?

Indelibly. What impressed me so much is that this was said with infinite sweetness by a wonderful person, a person who didn’t realize—and never would—what she was really saying. It kept spinning around in the back of my mind and I’m still trying to figure out what kind of society this is where someone can say something like that with such complete ease. In today’s Brazil, we can think of this in terms of a pattern of civilization, marked by a pendulum swinging between punishment and impunity. How was it possible to build such a society? There is no satisfactory interpretation of Brazil. It’s not enough to reiterate hundreds of times the horrors of slavery, a phenomenon that’s obviously fundamental to understanding the country. We must capture the finer aspects. For the last few years I’ve been irritatingly insistent on this—you can’t just work on the grand scheme of things. We have to consider a kind of fundamental motto: the more brutal the society, the more fine-tuned its analysis must be.

Do you mean that, in the case of Brazil, analyzing the principal historical processes would be insufficient to explain where we find ourselves now?

The great historical processes are obviously of great importance, but to understand their meanings, how this shapes an entire way of life and a way of confronting the public world of politics, it must be passed through increasingly fine filters. Regarding this, we find references—I would almost say illuminations—in the small, in the tiny. In the same way that Gabriel, the boy, was impacted by an incident that could be considered minimal and, in my case, it produced everything. Including my going into the social sciences.

We have to consider a kind of fundamental motto: the more brutal the society, the more fine-tuned its analysis must be

What was your admission to USP like?

In fact, I didn’t enter the university formally equipped for it. If there had been a fraction of the requirements there are today, I wouldn’t have made it through the door. I was terrible, I never managed to be a good student, not even at USP.

Aren’t you exaggerating?

You’re right, my wording is extreme. But really, if we were to consider my grade record, I don’t look good at all. However, I was lucky to have mentors who bet on me at the right moments. This happened during the university entrance exam, when an eminent professor failed me in the oral exam and it was counteracted, and also at the end of my bachelor’s degree, when Florestan Fernandes [1920–1995], who didn’t care about formalities, made the second and decisive bet. The good thing about this is that it allowed me to cultivate a taste for intellectual autonomy and thinking for myself.

To what do you attribute this academic difficulty?

In part, to the inconsistency and confusion in my life. Until close to 10 years of age I lived out there in the country, somewhat displaced. Then came the brutal shock of leaving that cozy little school and suddenly facing what would become the high school, in a competitive environment—in what was for me a metropolis—Jacareí. I couldn’t take it very well and began to distance myself. So much so that I obtained my diploma to enter the university not through the normal channels, but through an exam for students who hadn’t completed high school.

Did you go straight into social science?

Yes, and that was due, in part, to the encouragement of friends, especially Michael Löwy. The closest alternative would have been philosophy. Looking back, maybe I had more affinity with philosophy than with social science, because deep down what excites me is the world of ideas, the world of relationships translated into ideas. It is not, we could say, the world of manipulating objects or, much less, people. But it was good to have gone into the social sciences. It’s a terrific course; USP is a serious place. There you truly have an environment for reflection, teaching, and doing research. It has to be said, once again, that the public university system is absolutely indispensable. There’s no other place where it would be possible to find an environment like that, where the restlessness, the search for knowledge, the search for understanding about what happens in the world resonates at all times. That’s really true of USP and of FFLCH. A school which, within USP, is always seen with what we call friendly distrust.

And that’s the best-case scenario, right?

Yes, best case, because it’s the ugly duckling, despite being at the root of everything. It can’t even complete its building installations, because something more urgent always appears at another unit. When I was dean of the college, at the University Council meetings I often heard people say “This school of yours is impossible. It only creates problems, what kind of school is that?” I would say: “It’s very simple. We have more than 10,000 students just at the undergraduate level, spread over seven basic areas: philosophy, letters, history, geography, anthropology, sociology, and political science. You are all used to less complex situations.” I used to joke that FFLCH was bigger than the entire UNICAMP student body, it just didn’t have the budget. At FFLCH, you work a lot. The number of theses—most of them of good quality—produced per year is in the hundreds.

What torments me is how our dark side and our light side are so closely associated, so suffused within each other

Your academic trajectory is marked by your reflections on thinkers who wrote in German. Did you learn the language at home?

Exactly. I spoke German at home and Portuguese on the street. My brother, because he arrived here as a child, quickly began to master the Portuguese language and for a long time he was a kind of intermediary between my parents and the local community, and always treated very well. This is something I like to emphasize because it gives you a bit of an idea of the type of society we have—or used to have. My parents ended up in a remote spot in the Paraíba Valley, where there were no other foreigners, but they would always remember the enormous understanding, kindness, and solidarity they found among the country folk, who welcomed these people who didn’t know the language, who didn’t know about leaf-cutter ants but wanted to cultivate the land. It was beautiful because without this help they almost literally would not have survived. This is really the bright side of our society, and it was an extraordinary lesson. That’s why it’s my fervent hope that at least this feature of our Brazilian world isn’t affected by the horrific times we’re going through now. My assessment is that it will take at least 30 years, a generation, to rebuild the country after the disaster. The drama that torments me, and one must face it, is how our dark side and our light side are so closely associated, so suffused within each other.

But back to the language issue. When did you realize you were, in your own words, “the heroic man,” able to read Weber in German?

I was already reading it when I entered university, when I started frequenting the excellent foreign bookstores around São Paulo. In one of them, I was introduced, by a German bookseller, to Max Weber’s fundamental book, Economy and Society. “Here, this will interest you.” Once again, a single sentence from a woman changed my life.

What was your master’s program like?

In 1964 I joined CESIT [the Center for Industrial and Labor Sociology]. As there was not exactly a formal selection process for graduate students, at that time the center—created by Florestan Fernandes and Fernando Henrique Cardoso—functioned as a gateway. The model was different from the current system. There were no credits, nor the obligation to attend any courses. Basically, we were called there to do our research. Within the CESIT project, several studies were developed on important areas of the economy, on a national scale. I was given the task of working on the petroleum market. Under the guidance of Octavio Ianni [1926–2004], I began to research Petrobras. The initial idea was to understand the organization and how it works, but then something happened that’s quite common in our field: the tail wagged the dog. At that time, talking about the Petrobras organization involved telling how the state-owned company was created, which became the question that ended up dominating my research.

What was the chief conclusion of your master’s thesis?

The study was oriented towards examining the roles of different groups and economic sectors that formed what would be Petrobras’ eventual design. Taking advantage of postwar conditions, Getúlio Vargas [1882–1954] worked hard to get the steel industry up and running. In the oil sector, he was led to conclude that it wasn’t worth continuing with the proposal of a state monopoly. With this in mind, he adopted the idea of a mixed private-public company. That’s when one of those paradoxes of political life occurred. In addition to the leftist forces that strongly defended the monopoly, the UDN [National Democratic Union], which was a very important conservative liberal force, in their eagerness to oppose the President, decided to work against Vargas by supporting the state monopoly, which helped tip the balance in that direction.

In other words, contrary to the general movement of political science in Brazil, you began your academic thinking with a study in the area of institutions and later returned to theoretical thought?

In fact, it was a fundamentally institutional study and, according to an analysis of the bibliography done at the time by Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Bolivar Lamounier, in a way it anticipated the trend of undertaking studies about decision-making in Brazil.

In this sense, your master’s research is a contribution to Brazilian political science even though at that time you were in sociology.

Yeah, it’s interesting. I was in sociology, but the study is more of a political analysis than a sociological one. That changed in my doctorate, which is highly theoretical.

You have to do things that could be done by any other rational being, and these actions must have justifiable validity

How did this about-face, which in many ways might be considered radical, come about?

It was, again, thanks to Ianni, who realized the important role the mass media was playing in the changes affecting our society during the late 1960s. With his encouragement, I jumped in with both feet. And for the second time, I became “the man who spoke Javanese,” because I was that guy who was messing around in communication, something that nobody did at that time in Brazilian sociology.

What exactly did you research for your doctorate?

My research was in the field of sociology of communication, but instead of focusing on the issue of print journalism, television, or radio, I decided to investigate their foundations, the thing that’s at the core when one speaks of the sociological analysis of communication—in other words, how communication is organized and distributed within society. I explored the concept of cultural industry, developed by Adorno. The mass media form a system, hence the notion of the cultural industry. For my dissertation, I defended the idea that you can better capture this phenomenon within its specifics, by analyzing the product, in other words, the messages being disseminated, rather than the way it was constructed and disseminated. At the time, there was a tendency to say the mass media were inherently conservative, that they wanted to maintain society where it was. But this conflicts with the concept of cultural industry. What happens is that the most modern forms of communication, such as—at the time—Rede Globo, operate not only with an eye on the current audience, but are also attentive to trends within society. When new audiences—in other words, consumers—begin to appear, they make adjustments. In the 1980s, when female participation in society increased, programs such as Malu Mulher were created that responded to this change, even though they weren’t directed at a large mass audience. Cultural industry is attentive. It is fundamental to maintain the initiative. I joke that, quoting Lenin [Vladimir Ilyich Ulianov, 1870–1924], “it’s always one step, but never more than one step, ahead of the masses.”

You also often joke that Adorno is your guru. Why?

I have enormous sympathy for him and for Weber, but I have more for Adorno, a man who tried to keep alive and advance leftist thinking and analysis in the contemporary world. He leaned strongly towards Marxism, he was committed to it, although he wasn’t at all orthodox. Adorno was more concerned with the possibility of changing capitalist society, while Weber was engaged in a diagnosis of where society was and where it might be headed.

One was a man of action and the other more of reflection.

Exactly. The man of action was Weber, who even made an attempt at becoming a politician, and was a total realist. His intellectual project consisted in seeking sharp clarity about the state of affairs, and which trends could be perceived and followed. He didn’t have much sympathy for the countless currents of Marxist-inspired thinking, he considered them to be out of touch with reality. Adorno was the man who also tried, in his own way, to make a diagnosis. But, without any great hope or optimism, he was constantly betting on the possibility of finding ways to change the type of society shaped by capitalism. He was not, in the conventional sense of the term, an activist, but was a powerful intellectual who was publicly committed to, for example, human rights issues in postwar Germany. Although a talented pianist and composer, Adorno was not simply a man of aesthetic reflection. He committed himself, with determination, to the struggle against hardship in the world. Besides Weber and Adorno, there’s another figure always present in the background, as a kind of “honored outsider:” Rosa Luxemburg. She is my patron saint. I admire her as an intellectual, as an activist for good causes, and for the wonderful kind of human being that she was. She ended up getting executed in 1919, by the militias of the time, like a kind of super-Marielle [Franco, 1979–2018].

Your qualifying thesis for professorship, “Crítica e resignação, fundamentos da sociologia de Max Weber” [Criticism and resignation, the foundations of Max Weber’s sociology], has been considered one of the most sophisticated works of Brazilian sociological theory. Despite this, soon after defending it, you moved into political science. How did that come about?

That change was just one of those little things in professional life. At a certain point it became clear that my sociology colleagues were no longer comfortable with me there. This was during the period when the departments were being created at the school. Encouraged by my colleagues in the area of politics, I ended up changing departments. But to this day, nobody sees me as a political scientist, I’m still a sociologist. My intellectual identification is with sociology, but what gave me more opportunities was political science, including the great joy of becoming a professor emeritus.

How can we live with so much insensitivity, violence, injustice, oppression, and indifference?

Analyzing your intellectual production, it’s clear that it was through political science that you took up that one issue, involving rationality and justice, which marked your childhood at the country school.

You’re right, it came back with a vengeance during that transition, and for that reason it fell to me to introduce a new area of research into the program—normative political theory—focused on the issue of justice and the forms of democracy.

Could you talk a little about the role the concepts of rationality and justice played in your scientific work?

I would say they are my compass. They are basic concepts that always appear to be a necessity, although we know it will never be possible to fully achieve them. I wouldn’t be able to do anything without these two reference points. The problem is, how is it possible to this translate this into our everyday relationships and social organization, so that they are fair, and maintained on a foundation of reason?

What kind of reason are you talking about? And which conception of justice does it refer to?

I’m not an unconditional devotee of [Jürgen] Habermas, but he has a good idea of what a rationally organized, democratic world would be like. Habermas sees rationality in terms of the ability to reach a well-founded consensus—shared positions, so to speak—through rational dialogue. Even though provisional, such agreements can be maintained in the face of disputes. Rationality would be the ability to present reasons for actions and positions. This is a very ingenious way of looking at the question of reason, not as some kind of abstract quality, but as an integral part of a society free from any dogmatic attitude. My conception of justice, on the other hand, comes down from the great Kantian heritage. You have to think universally, you have to do things that could be done by any other rational being, and these actions must have justifiable validity. One must find the solution that is generally valid for all. The democratic component lies in the fact that you act in an egalitarian manner for the whole, so that everyone can be integrated into the common world in a well-substantiated way.

What are you working on right now?

At the moment, I’m preparing the third volume of collections of my articles that have been published for some time—or were never published—with the general title “Weber, Frankfurt.” The first volume was subtitled “Theory and Social Thought” and the second, about to be released, “Modes of Thought.” The third will have the subtitle “Brazil as a problem.” In the first there are five texts on authors, specifically Weber and Adorno, and eight on themes such as civilization and development. The second focuses, in 13 articles about 10 authors, on their respective “ways of thinking.” For the third, 12 articles are planned, of which five are thematic, ranging from culture to industrialization, and seven are interpretations of Brazilian authors. The motivation for all this comes from my fundamental concerns regarding Brazil today, at a time when we are outraged and shocked by a kind of institutional degradation and by the behavior of those in power. What’s often lost sight of is that none of this is new. The present moment makes explicit in an extreme way, to the point of caricature, trends that have existed in our society for a long time. It brings me back to the question that seems fundamental to me, of the “difficult republic.” The enormous difficulty we’ve experienced, throughout our history, in constituting some form of republican coexistence. The essential question is: how have we managed to create a society like this? A society that conveys a warm, friendly image, but when you look closely, it’s one of the cruelest on the planet. How was this horror, which permeates everything, created? How can we live with so much insensitivity, violence, injustice, oppression, and indifference? With the exception of my master’s thesis, this is the type of question that runs like a red thread through all the work I’ve developed over my nearly half-century long career. And that’s what I intend to come back to next.