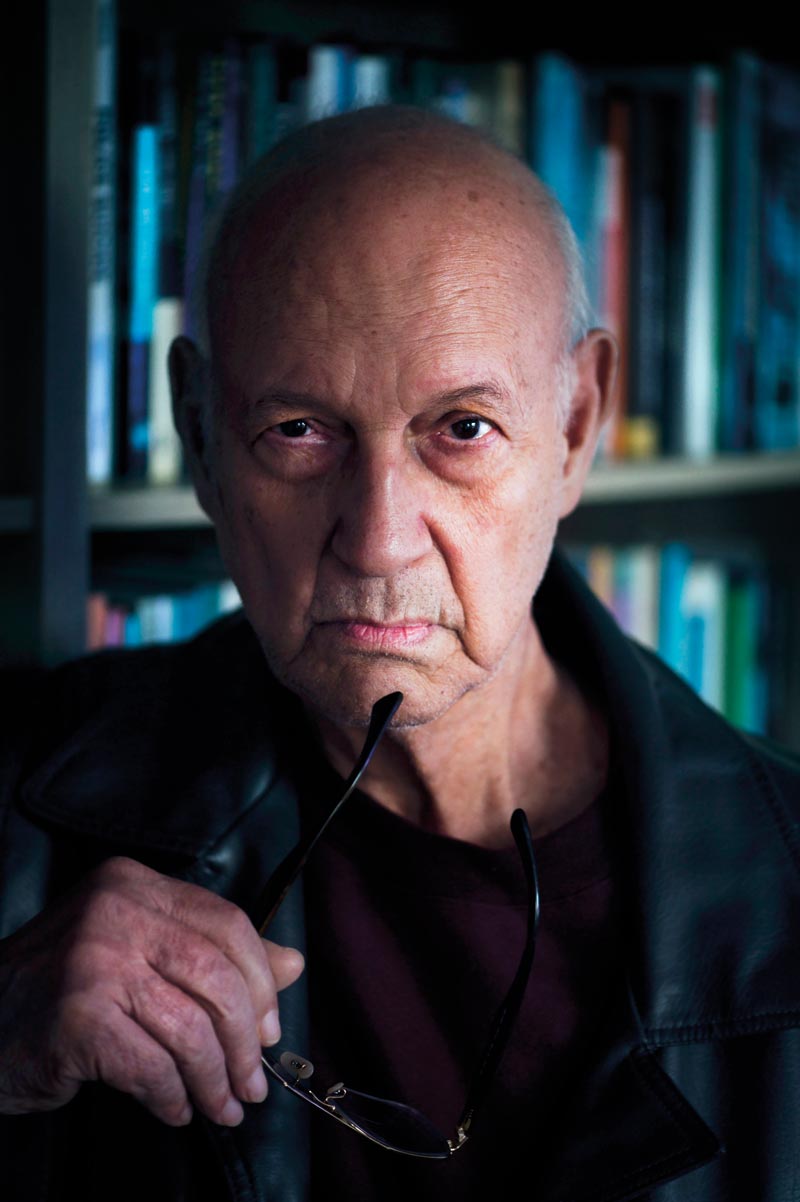

Léo Ramos Chaves“I often say that I stumbled into law, I didn’t choose it,” says Rio de Janeiro native Gláucio Soares, who was a student in the first class at the Cândido Mendes University Law School in Rio de Janeiro. The only child of an elementary school teacher and an accountant, Soares entered the university in 1953, at a time when political science and sociology weren’t autonomous disciplines, “but chapters of law.” It didn’t take long for him to become enchanted with the social sciences. “The specific area of knowledge that I fell in love with wasn’t represented in Brazil and was stimulated by what I read: books dealing with research and the results of research,” he recalls. “The PUC [Pontifical Catholic University] sociology and politics program had much more impact on me than the law school.”

Léo Ramos Chaves“I often say that I stumbled into law, I didn’t choose it,” says Rio de Janeiro native Gláucio Soares, who was a student in the first class at the Cândido Mendes University Law School in Rio de Janeiro. The only child of an elementary school teacher and an accountant, Soares entered the university in 1953, at a time when political science and sociology weren’t autonomous disciplines, “but chapters of law.” It didn’t take long for him to become enchanted with the social sciences. “The specific area of knowledge that I fell in love with wasn’t represented in Brazil and was stimulated by what I read: books dealing with research and the results of research,” he recalls. “The PUC [Pontifical Catholic University] sociology and politics program had much more impact on me than the law school.”

Considered one of the founders of modern sociology in Brazil, Soares innovated by applying qualitative and quantitative methods to social research. In 1967, with the publication of the article “Socioeconomic variables and voting for the radical left: Chile, 1952,” written in partnership with Robert Hamblin, a professor of social psychology at Washington University in St. Louis, in the United States, Soares became the first Latin American to publish in the American Political Science Review. His book Sociedade e política no Brasil (Society and Politics in Brazil), released in 1973, quickly became a reference among works of Brazilian electoral sociology. “The suggestion to publish it through Difusão Europeia [Difel] was made by Fernando Henrique Cardoso,” he says, noting that the two were in Chile together. “At that time he, and almost everyone in the academic world, was to my left, politically. I went to the left without moving because Brazil went to the right,” he says.

A professor at the Institute of Social and Political Studies of the State University of Rio de Janeiro (IESP-UERJ), Soares says he likes to write: “I used to worry about elegance, now I want to reach the soul of the person reading. I believe in the soul.” A father of five and grandfather of six, in this interview, given at the apartment where he lives with his wife (political scientist Dayse Miranda) across the street from the Fluminense club headquarters in the south of Rio, Soares talks about his professional career and his latest research subject.

Specialties

Political sociology and criminology

Institution

Institute of Social and Political Studies of the State University of Rio de Janeiro (IESP-UERJ)

Education

Law degree from Cândido Mendes University (1957), studies in sociology and politics at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (1958), master’s degree in law from Tulane University (1959), doctorate in sociology (1965) from Washington University in St. Louis

Production

11 books written or edited, 43 book chapters

You studied law, sociology, and political science. When you need to specify your profession, how do you define yourself?

I play around with that a little. Sometimes I put sociologist. In recent years I’ve been working a lot with criminology, but not criminal law or criminal prosecution. I don’t consider myself a legal expert at all. I became disenchanted with law very quickly.

Why?

Because the law doesn’t allow for essential statements such as: “I don’t know, however, I want to know.” It’s: “I already know.” It goes beyond the differences between sciences of what is and of what should be. The attitude that “I now admit my ignorance, so I need to do research” is what science represents to me. It is also a barrier I’ve encountered. Not just in the discipline, in the case of law, but also in the theoretical. Some theories were imported as answers and not as problems to be solved.

You didn’t see a scientific challenge in law?

I don’t believe there was a scientific challenge. Here in Brazil, I saw the application of statutes. I have a master’s degree in comparative law and today this knowledge serves as a parameter for me. Knowing, from the inside, how a law scholar thinks, I contrast it with the thinking of an effective researcher. In other words, there was disenchantment, but also utility.

It’s clear from your work that you’re somewhat concerned about research methods in social science. Where does that come from?

I got a bit of shock treatment with my first readings, even before going to the United States. On the one hand were statements being freely made in the name of sociology and political science, and on the other, questions to be answered. I wondered: do we really know all this? Of course not. I remember fighting with orthodox Marxists who, looking for a solution to Brazilian problems, read, for example, The Communist Manifesto of 1848. The most intelligent of them appealed to the Grundrisse, which is the research that [Karl] Marx [1818–1883] published in the late 1850s. People don’t know Marx the researcher. They know Marx the theorist, the revolutionary.

And you were only interested in Marx the researcher?

It was what interested me most, certainly. Marx spent 13 years in a library searching, for example, for historical information sets on salaries. I discovered this in Paris, almost by chance, when I came across the work in a bookstore.

Returning to your concern with research methods—in an article published 15 years ago you remarked on what you considered to be the “questionable teaching of research techniques and quantitative methods.” What’s changed since then?

Perhaps the differences between the disciplines have become larger over this period. There was a time in political science—which didn’t happen in sociology—when a group of people who had good master’s degrees in Brazil returned from the United States with good doctorates. In Minas Gerais, Júlio Barbosa created a postgraduate scholarship program, back when they hardly existed, which led to the establishment of an intellectual elite, a generation that’s at least 70 years old today. Each of those who came back, well trained in methods, gave me new hope. Because there is so much to discover. We don’t have to spend the whole day philosophizing, reading [Johann Wolfgang von] Goethe [1749–1832] and [Friederich] Nietzsche [1844–1900]. In Brazil, the use of methods in political science has improved somewhat. In sociology, we haven’t had the same development of qualitative methods we’ve had in anthropology.

So in your assessment, if we look at the social sciences currently, sociology appears to be at a disadvantage.

In terms of methodological rigor, yes. The use of European classics, which were taught as being authoritative, was very harmful. To some extent the same thing occurred in sociology that happens in law, where what has the most weight is authority. The idea of authority is detrimental to science. In science, it doesn’t matter who, but what, and how. The name of who does it is irrelevant, but when it’s mythologized, the student tends to take in that knowledge as the truth. Period. Take the case of [Émile] Durkheim [1858–1917], undoubtedly a great French researcher and thinker. In Brazilian academics, when it comes to suicide, the first work that comes to mind is his Suicide, published in 1897. But in France itself, 50 years before Durkheim, [André-Michel] Guerry [1802–1866] produced interesting data. You only have to enter the term “suicide” in Google Scholar to find hundreds of thousands of research papers on the subject. Five or six years ago I did an analysis, which I didn’t publish, of the content of subjects taught to postgraduates, which revealed some interesting things.

For example?

I did a national survey, on syllabuses and bibliographies for sociology programs that offer postgraduate degrees, and checked who the recommended authors were. The principal recommendations were Europeans. There were also some Americans, a few Brazilians, and virtually no other Latin Americans. There were no Africans and Asians. This is not to say that there isn’t any social science in Asia and Africa. This means that we simply ignore their production. The title of that study would have been “antiquated sociology.” I didn’t publish it because I would’ve had to devote more time than I had available to finish the work and update the data, and there would have been a lot of brawling. I wasn’t eager to get into that fight.

But it was your passion for sociology that made you leave Brazil in the late 1950s.

Yes, I decided to leave in order to develop myself. It was a risky decision. Before leaving, the only conversation I had on the subject was with Father [Fernando Bastos de] Ávila [1918–2010], founder of the Institute of Sociology and Political Science at PUC. Responding to my hesitance, he told me, “Outside Brazil the resources are so much greater that, no matter what, you will learn.” My first destination was Tulane University, in the United States. I got my master’s degree in one year. Then I went to the National Opinion Research Center [NORC], to learn how to do research.

Many academics were on my left. I went to the left without moving because Brazil went to the right

What was that learning experience like?

The first lesson was that in the social sciences it’s possible to produce knowledge based on data collected by interviewers, organized by codifiers, and analyzed by statisticians, without ever having seen the interviewee. The second lesson came in the field and limits the first. Those who do not do interviews lose a lot. I was thrown into the field to see if I’d survive; I was paid per interview, in ice-cold Chicago. One of the authors of the research was the sociologist Elihu Katz, and in the questionnaire he had prepared there were a lot of questions regarding abortion. I was tasked with interviewing residents of an Italian neighborhood. One woman didn’t want to answer, she complained to a group of men and the guys ganged up on me. I had to run away. And in that moment I understood that I had asked questions that, in their subculture, it wasn’t possible to ask. Then I realized that the topic of abortion could be studied, but the methodology would have to be different.

You were also one of the pioneers in electoral research in Brazil. How did that happen?

It was during the 1960 election. The election for governor in the then state of Guanabara was quite heated. On the right, Carlos Lacerda [1914–1977], from the UDN [National Democratic Union]. On the left, Sérgio Magalhães [1916–1991], from the PTB [Brazilian Labor Party]. And a third candidate, Tenório Cavalcanti [1906–1987], kind of charismatic, kind of violent, with more of a presence in the Baixada Fluminense [a northern Rio district], who was with the PST [Social Labor Party]. There were several surveys, which at the time were called previews. One of the most ambitious was done by the newspaper Correio da Manhã [The morning post]. I thought: this is my chance. I put on my only suit and went to report to the Correio. The study was contracted, I went into the newspaper offices in the morning and left that night with the printed questionnaire. There were 40 or so questions. I trained the interviewers, but there was a lot of trouble with the veracity of the data, and dishonesty. There were two types of fraud. The most common: the subject would go to the place where the research was to be conducted, ask two or three initial questions, and leave, then fill out the rest of the questionnaire at home. Others didn’t even go, they filled everything in at home. We had a crosschecking system, which allowed me to detect fraud and redo the interviews. Using official data from the TRE [Regional Electoral Court], we weighted the results according to electoral zones. There was some deviation, but I got the election result right: Lacerda won, but only by a small margin.

Did you receive accolades in the end?

No, in the end I ran off. Tenório Cavalcanti, who was an aggressive politician known as “the man in the black cape,” always carried a machine gun, nicknamed Lurdinha. He sent a letter to the newspaper, saying something like: “Intellectuals create their lies, and end up believing them. You are wrong sir, and you are damaging me.” I don’t know if my fear drove my interpretation of it or if my interpretation intensified my fear. The fact is that I decided to leave Rio. I went to Brasília, for the inauguration of the new capital. The people at Correio da Manhã were irate with me because I’d promised two more articles that I ended up not delivering. But the quality of the research was recognized, even by the competing newspaper.

You had the opportunity to establish yourself in the area of electoral and market research, but you declined. Why?

At that time, when Marplan invited me to work for them, I was living with my parents, and I lived on practically nothing. It was a life decision. If I had accepted, within a few months I would have bought a car and rented an apartment in a nice part of town, satisfying my repressed bourgeois leanings, and I wouldn’t have returned to the academic world anytime soon. I chose to continue toughing it out. I never regretted it.

What does science give you that the market wouldn’t have given you?

An identification with the fruits of my work. It gives both joy and sadness. It’s much more emotional, but I control the effects of that emotion using rigorous techniques. I use them even when doing content analysis. While I was at Washington University, Gilbert Shapiro, my sociology professor, for example, analyzed the 1789 Cahiers de Doléances, the lists of grievances recorded by the French people shortly before the Revolution. He was a scholar. This captivated me. Nobody did such careful and detailed work and I thought: I want to do this someday!

Teaching the European classics as if they were authoritative is harmful. The idea of authority is detrimental to science

When did you start doing content analysis?

Quite some time ago. However, more recently, when Google facilitated access to its 30 million books, a new type of analysis became possible for people like me, who wanted to test the evolution of Marxism, as a theory, and its concepts. I selected basic content that might be found in the books by searching, such as “class consciousness” and “class conflict,” “proletariat,” and “bourgeoisie.” I worked in five languages, English, German, French, Spanish, and Italian. The idea was to verify what affect the end of the USSR [Union of Soviet Socialist Republics] had on the dissemination of the concept. I didn’t have an integrated set of hypotheses; I had only my curiosity. For example, I wanted to know if the decline had started before the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Then I decided to find out, still following this empirical-analysis thinking, what happened with the thinking of ECLAC [Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean] and the ECLAC members. And with the censorship of [Leon] Trotsky [1879–1940] in Nazi Germany.

What did you discover?

ECLAC didn’t die, it reinvented itself. Regarding Marxism, two conclusions can be established. There is no sociological theory that’s had as much impact, over so long a time, as Marxism. Marxism followed the path expected of a grand theory: it dominated sociological thinking for decades while being affected by events in national and global politics, then went into a rapid decline, which continued at the beginning of this millennium. It’s broad, overall theoretical direction has been replaced by several directions with reduced scopes and ambitions. This tool for analyzing the frequency of references, which is less sophisticated, is what I use to reflect on the directions taken in political science and sociology. The more sophisticated, more accurate version is Google’s own algorithm, Ngram. It was this tool that I used to reflect on the rise and fall of Marxism. References to Trotsky in Russian plummeted after the collapse. They were already starting to fall in the years before the rise of [Adolf] Hitler [1889–1945], and only started to go up again after Nazism.

Your doctoral thesis on economic development and political radicalism also remains unpublished.

I did not publish my thesis, which I defended in 1965. At that time, I was still flirting with finding a path that would be more intelligent and creative than Marxism. I used a concept by the American sociologist Robert Merton [1910–2003] to explain the radical leftist vote, throughout the world. I analyzed a lot of indicators. As a result, two factors emerged that aren’t orthogonal, aren’t independent of each other, they correlate, but are not identical. I called one economic development and the other social development. It is the gap between the two that explains the radical vote.

When did you become interested in the subject of violence?

I saw what [Augusto] Pinochet [1915–2006] did in Chile. When I was at FLACSO [Latin American School of Social Sciences], I went to Argentina and saw what the Argentine military did. And here, too. I spent 21 years collecting data on the sly, in Brazil. My initial articles on the subject showed, for example, that the political expulsions that occurred during the dictatorship [1964–1985] were influenced first by the relationship the politician had with the FPN [National Parliamentary Front], second, by the party that he was affiliated with. Years later, it predominated the way he voted for projects that were of interest to the government. It was what defined whether they lost their mandates or not. The legislative part of this research was done with Sérgio Abranches. My interest in the topic, which started with the political violence in Chile, Argentina, and Brazil, was later aimed towards violence in society.

Reducing violence begins with gun control and continues through the use of scientific knowledge

You did more than two decades of research in this area. What works would you highlight?

The book Não matarás [Thou shalt not kill, (FGV, 2008)]. I worked on it for more than 10 years. I also like a study on the impact of the Disarmament Statute, which I did with Daniel Cerqueira, from IPEA [Institute of Applied Economic Research]. Our estimate is that during the first 13 years it was in force, in other words, until 2016, the statute saved 121,000 lives. It is a work of science communication, which emphasizes the need to discuss the effects of the statute not only from the moment it came into force, but to analyze it in relation to the previous trend in the homicide rate, which was one of increasingly rapid growth. The results leave no doubt: firearms are a disaster. Owning them dramatically increases the number of domestic accidents. The book As vítimas ocultas da violência no Rio de Janeiro [The hidden victims of violence in Rio de Janeiro; Civilização Brasileira, 2007], which I published with Dayse Miranda and Doriam Borges, is pertinent as it shows the suffering—largely ignored—of the many people who have their lives destroyed, for each violent death reported.

In Brazil’s case, is it possible to solve the problem of violence?

We can’t solve it in the sense of ending violence. But we can reduce it, and this begins with gun control and continues by using scientific knowledge in the service of public policy. We know, for example, that those who finish high school have only one-third the risk of being murdered compared to those who aren’t in school. Boys are 12 times more susceptible than girls, and being black is an important risk factor. If we picture one man standing on the shoulders of another, and so on, successively, the lives saved would reach a height of ten kilometers, if the homicide rate among blacks were identical to that of whites. Doriam Borges and I used this data in the article “The Color of Death.”

For many years you taught abroad. What was that experience like?

I taught in the United States, England, Chile, and Mexico. I lectured more in the United States than here, in Brazil. I spent 40 years teaching classes and doing research abroad. American students are, in the best sense of the word, squares. They’re obedient, do what’s agreed upon, read what you tell them to read. The people at FLACSO reflected Latin America at the time: students from the Southern Cone arrived much better prepared than the rest.

You have 31 master’s and 11 doctoral students you’re advising. Do you like advising postgrads?

I’ve advised a lot of people, it’s a pleasure, but it’s also a source of anxiety. I’ve frequently agreed to advise “complicated” people, based on a study we did at FLACSO in the early 1960s. This study indicated that the university lost more students due to personal problems than academic difficulties. From my experience, I’d venture to say that over the years university education in Brazil has deteriorated. But this is a necessary price, which has to be paid. The democratization of society means that the university no longer belongs only to the elite.

Brazilian sociology has carefully avoided dealing with emotions. Human beings experiences love. Why not study love?

How did you deal with research funding throughout your career?

Today I only conduct “artisanal” research. I believe in this method. I was very influenced by C. Wright Mills. I have rarely been able to count on funding. I don’t have a nose for detecting sources of funding. I try to cover every stage of the investigation personally. When I went to Tulane, New Orleans, I had a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, and received US$132 a month. Here, I had a grant from FAPERJ [Rio de Janeiro Research Foundation]. It’s given to all the old people at IESP, ever since the incorporation of IUPERJ [Rio de Janeiro University Research Institute]. The grant is less than R$5,000 and I call it a graveyard grant because to receive it, you have to be over 70 years old, with some public prestige, and ideally die within three years. I didn’t die, but almost, and the grant ran out.

You once wrote that you consider it “dangerous” to separate the political and academic spheres. Why?

These are two arenas with a significant intersection. You learn, and bring to the academic world realities that aren’t studied professionally, through simply observing conversations, for example. This all enriches the academic arena. If you lock yourself in an ivory tower, you lose touch with reality. This is where I get my interest in empiricism. Empiricism is you, in some way, getting in touch with reality. Continuously.

Is that also where your choice of topics, which are considered somewhat unorthodox in the academic world, comes from? What are you researching now?

For the past three years I’ve been involved in a project called “Migalhas de amor” [Fragments of love]. Brazilian sociology has carefully avoided dealing with emotions. Outside the classroom, we talk about love all the time. The human being experiences love. Why not study love? How many people study love in Brazil? I started with the humanities journals indexed in Scielo and, after using their search engines, I found that less than 1% of the articles mention the word love. We also don’t study happiness in Brazil. We don’t study emotions in the social sciences. This is in contrast, for example, with the Netherlands, where there is a center dedicated to researching this topic. I see love as something extremely powerful, and I started to analyze the academic literature—where there is secondary data, I grab it.

What do you want to understand with this research?

Well, what effect does love have on social relationships, for example? We now know that children who have both parents at home are less affected by problems involving low grades, alcohol, cigarettes, and drugs. What appears in the scientific literature goes further: parents who read with their children, dedicate time to their children, praise them when they succeed, and are able to discipline, produce children with lower risks. Physical presence and the expression of affection are very important. They greatly reduce, for example, the risk of suicide. Outside the family, expressions of love are also relevant. Elderly people who had no children and, therefore, don’t have grandchildren, but who help other people, live longer, studies indicate. Loneliness, a subject that appears with increasing frequency when we analyze the scientific literature produced over the last 200 years, is the big killer in the elderly and advanced elderly populations. These are also preventable deaths that are waiting for intelligent public policies.