Brazilian poet Gonçalves Dias (1823–1864), described by the sociologist Gilberto Freyre (1900–1987) as “half Portuguese, half cafuza [of mixed Indian and African heritage],” was sent to Coimbra at the age of 15 to study law. It was in the Portuguese city in July 1843 that under the influence of European romanticism, he wrote the famous poem “Canção do exílio” (“Exile song”), expressing his longing for his home country. Upon returning to Brazil in 1845, however, the young man realized that he was not in the paradise of palm trees and birdsong that he had written about in his poem, but in a slave system that in his view, needed to be overthrown. “Black men’s hands are bound by long iron chains, the rings linked from one to the next, eternal like their curse passed from father to son,” he wrote about monarchical Brazil in the text “Meditação” (“Meditation”), published in Guanabara, Brazil’s most important Romantic magazine, in 1850.

Called “the first abolitionist cry of Brazilian poetry,” by fellow poet Manuel Bandeira (1886–1968), “Meditation” reveals a little-known critical aspect of the author who was a key figure in Brazilian Indianism in the mid-nineteenth century, alongside José de Alencar (1829–1877). “Much of Gonçalves Dias’s work was overlooked by the critics, who only paid attention to ‘Exile song’ and his Indianist poems. But he only wrote 14 poems on this topic,” says Wilton José Marques, professor of Brazilian literature at the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar). “His work is much greater than that. He was a Romantic poet in the broad sense of the word,” continues the scholar, who edited the book A ideia com a paixão: Gonçalves Dias pela crítica contemporânea (The idea with the passion: Gonçalves Dias in contemporary criticism; Alameda, 2023) together with Andréa Sirihal Werkema, professor of Brazilian literature at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ).

The book is a collection of 12 articles about the poet’s life and work. In one of the texts, Ana Karla Canarinos, also a literature professor at UERJ, interprets “Meditation” as a precursor of Brazilian sociological essays. According to the scholar, the poetic prose foretold discussions about the effects of slavery on the country’s formation that only began in the following century by intellectuals such as Gilberto Freyre and the sociologist Sérgio Buarque de Holanda (1902–1982). “Gonçalves Dias called for the end of slavery long before abolitionists like Joaquim Nabuco [1849–1920],” says Canarinos.

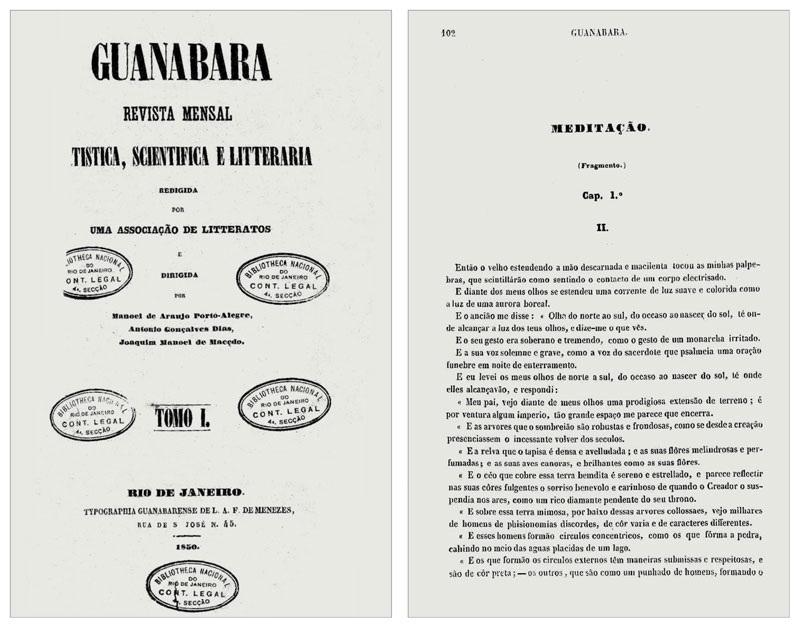

Brazilian National Library ArchiveIn 1850, Gonçalves Dias published the text “Meditação” (“Meditation”) in the magazine Guanabara Brazilian National Library Archive

“It is a virulent text, with an extremely negative view of Portuguese colonization and the Brazilian political elite,” adds Marques, who also wrote the book Gonçalves Dias: O poeta na contramão (Gonçalves Dias: The poet who went against the grain; EdUFSCar, 2010), published with funding from FAPESP. According to the researcher, the excerpts of “Meditation” that contained scathing criticisms of politicians from the Regency period only came to light when more of his work was published posthumously in 1868 and 1869. This is because Romantic writers generally did not want to risk dealing with the thorny issue of slavery, since many maintained mutually beneficial relationships with the government—Gonçalves Dias included. In 1849, the poet was awarded the Imperial Order of the Rose by Dom Pedro II (1825–1891) for his work leading the Guanabara magazine, which he founded together with the writers Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre (1806–1879) and Joaquim Manuel de Macedo (1820–1882). At around the same time, he became the first history professor in Brazil at Colégio Pedro II, Rio de Janeiro, and dedicated his unfinished Indianist epic Os Timbiras (The Timbiras; 1857) to the monarch. “Gonçalves Dias fell in love with the emperor, with whom he had an ambiguous relationship. He could not openly criticize the government, because he was supported by it,” Canarinos says of the author, whose bicentenary was celebrated in August last year.

The editors of the collection believe the sparse festivities surrounding the date—with the exception of the state of Maranhão, which celebrated the anniversary with a series of events—fail to reflect his importance to Brazilian culture. In Werkema’s opinion, one of the reasons Dias gets forgotten is that the stereotype of the country forged in poems such as “Exile song” and “I-Juca Pirama” does not resonate in the twenty-first century, when topics such as decolonialism and the deconstruction of the nation-state are being discussed in the field of literature. “This ‘cliché of Brazilianness’ may bother contemporary readers because it obfuscates the genocide and cultural erasure of Indigenous peoples,” she states. “But judging a nineteenth-century man by current ethical and moral standards equally risks erasing his contributions.”

According to Werkema, Gonçalves Dias had several talents. In addition to being a poet, he was a playwright and a traveling researcher, for example. “He thought about the Indigenous issue not only in a literary way, but also in an ethnographic way [see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 179]. He carried out several studies on the subject at the Brazilian Historical and Geographical Institute, including writing the Dicionário da língua tupi, chamada língua geral dos indígenas do Brasil [Dictionary of the Tupi language, known as the general language of the Indigenous people of Brazil; 1858],” says Marques. He was also part of the Imperial Scientific Commission (1859–60), together with geologists, geographers, astronomers, zoologists, and botanists, having visited Ceará and Amazonas. On that occasion, he even sent ethnographic objects to Rio de Janeiro, which were later incorporated into the National Museum.

Leonardo Davino de Oliveira, a literature professor at UERJ, says “Exile song” set in stone an image of Brazil that went beyond literature. The poem, which is extremely musical, was written in redondilhas (a traditional Portuguese verse form of five or seven syllables per line) and without adjectives. It is the opening poem in Primeiros cantos (First chants; 1846–47), Gonçalves Dias’s debut book. Its verses were incorporated into the national anthem and are part of the collective memory of Brazilians. “In that post-Independence era, our colors, our fauna, our flora were sung with jingoism, to set us apart from our colonizers,” explains the researcher.

Gilberto Inácio Gonçalves / Personal Archive | Wikimedia CommonsThe poem “Exile song” inspired a carnival march in the 1930s, performed by Carmen Miranda, as well as the song “Marginália II,” one of the tracks on the album Gilberto Gil (1968)Gilberto Inácio Gonçalves / Personal Archive | Wikimedia Commons

In the twentieth century, however, the poem became a “problem” for popular writers and composers tasked with constructing Brazil’s national identity: parodies and reinterpretations were created by authors such as Oswald de Andrade (“Minha terra tem palmares” [“My land has palm trees”]), Murilo Mendes (“Minha terra tem macieiras da Califórnia/ onde cantam gaturanos de Veneza” [“My land has apple trees from California/ where Venetian finches sing”]), Carlos Drummond de Andrade (“Um sabiá/ na palmeira, longe” [“A thrush/ on the palm tree, far away”]), and Ferreira Gullar (“Minha amada tem palmeiras/ Onde cantam passarinhos” [“My beloved land has palm trees/ Where the birds sing”]). “The modernists of the twentieth century had a critical view of the nineteenth century and revised Gonçalves Dias’s poem countless times,” says Oliveira, whose book examines the ripples of Gonçalves Dias’s famous verses that spread through Brazilian popular music.

They are present, for example, in the march “Minha terra tem palmeiras” [“My land has palm trees”], which was a major hit at the 1937 carnival. Written by the duo João de Barro (1907–2006) and Alberto Ribeiro (1902–1971), the song was performed by Carmem Miranda (1909–1955). Or in “Marginália II” (1968) by Gilberto Gil and Torquato Neto (1944–1972), a song written in the midst of counterculture and the military dictatorship (1964–1985), with the lyrics: “Minha terra tem palmeiras/ onde sopra o vento forte/ Da fome, do medo e muito/ Principalmente da morte” (“My land has palm trees/ where the wind blows strong/ Hunger, fear, and much more/ Mainly of death”). In 1984, toward the end of the military dictatorship, singer Gal Costa (1945–2022) recorded “Ave Nossa,” written by Beu Machado and Moraes Moreira (1947–2020): “Minha terra tem pauleira/ Desencanta e faz chorar/ Mas tem um fio de esperança/ Quando canta e quando dança/ No assobio do sabiá” (“My land has palm trees/ It disenchants you, makes you cry/ But there is a thread of hope/ When it sings, when it dances/ To the song of the thrush”). In the article, Oliveira also notes that the poem lent its name to the 1984 album Canção do exílio (“Exile song”) by samba artist Paulo Diniz (1940–2022) and the 1987 song by Ubiratan Sousa and Souza Neto, recorded by singer Alcione to the Maranhão rhythm of the Creole drum. “It is a poem that speaks to everyone who feels outcast to some extent,” he says.

In November 1864, a ship left the port of Le Havre in France, heading to Brazil with Gonçalves Dias aboard after another stay in Europe. Before it could reach its destination, it sank off the northeastern coast of Brazil. The author was unable to fulfill his desire to spend the last days of his life in his homeland, as he wrote in the verses “Não permita Deus que eu morra/ sem que volte para lá” (“God don’t let me die/ Before I go back”). Already in poor health at the age of 41, the poet was the only victim of the disaster, although the original work of The Timbiras may also have been lost, as was—supposedly—most of the ethnographic work he did for the Imperial Scientific Commission.

Years later, he would be honored by Brazilian writer Machado de Assis (1839–1908) with a long poem in which a “virgin Indian woman” sings a funeral song for the poet. “Morto, é morto o cantor dos meus guerreiros! Virgens da mata, suspirai comigo!” (“Dead, the singer of my warriors is dead! Virgins of the forest, mourn with me!”), he wrote in “Gonçalves Dias,” from the book Americanas (1875). In 1901, a bust of the Maranhão native was inaugurated at the Passeio Público park in Rio de Janeiro, at which time Machado de Assis declared: “The song is in all of us, like the other songs that he spread through life and the world […] everything that the elderly hear in their youth, and the younger ones continue to hear, and those that come next will hear, and so it will continue, while the language that we speak is the language of our destinies.”

Republish