The Brazilian Federal Government’s fiscal austerity program could slow the rate of decline in premature mortality in Brazil over a period extending to 2030. Premature mortality measures the number of deaths of individuals younger than 70—often associated with respiratory infections, high blood pressure, malnutrition, and other health problems—that could have been prevented had those individuals had access to primary care either at home or at local clinics. These conclusions were drawn by an international group led by Italian biologist Davide Rasella, of the Institute for Collective Health at the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA). He and his team modeled the potential impacts on coverage provided by two primary healthcare programs, Estratégia Saúde da Família (ESF) and Mais Médicos, after a constitutional amendment imposed a 20-year cap on government spending in 2016.

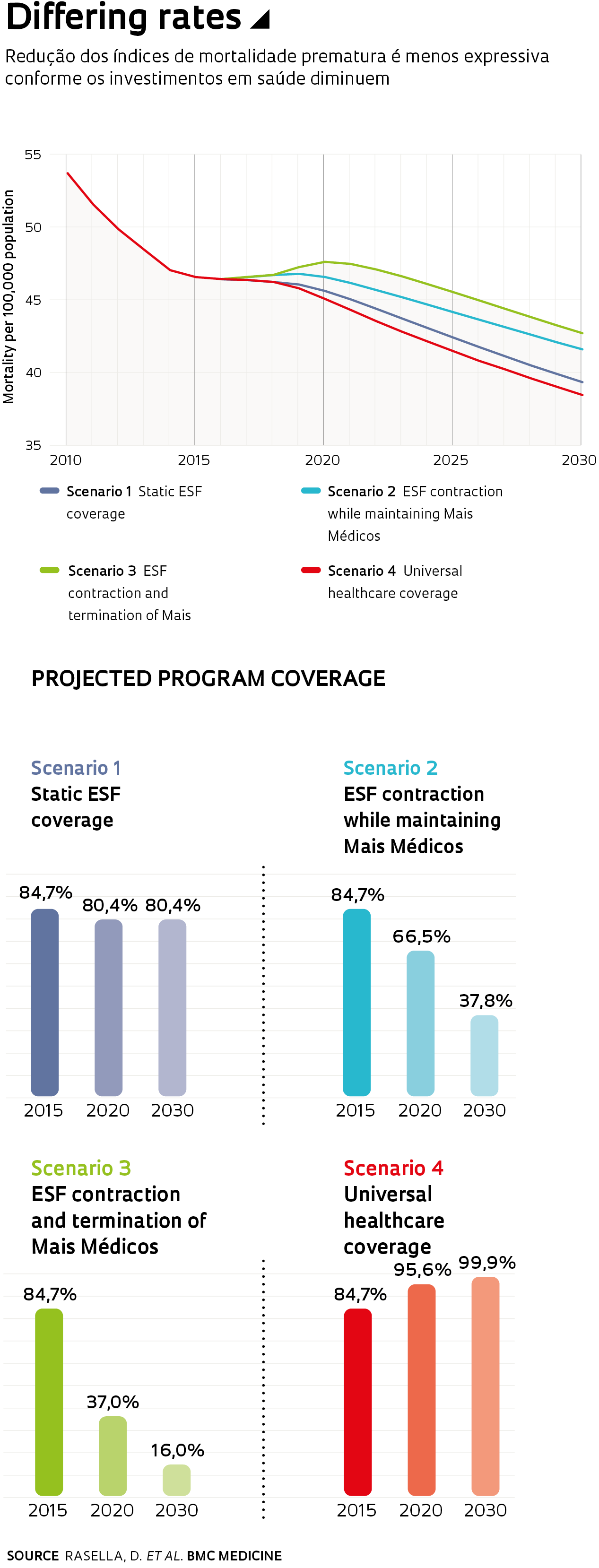

Using mathematical and statistical modeling, they estimated the effects of government spending cuts in healthcare on 5,507 Brazilian municipalities. Their modeling work was based on data available from the World Bank, the Brazilian Ministry of Health, the Brazilian Institute of Geography, and Statistics (IBGE) and the Institute for Applied Economic Research (IPEA). The study, published in April in BMC Medicine, modeled potential impact over the next 10 years in four scenarios. In one scenario, ESF coverage remains relatively constant at 80.4% of the population in 2030—compared with 84.7% currently. In a second scenario, ESF coverage is reduced to 37.8%, but the Mais Médicos program is maintained. A third, worst-case scenario models the termination of Mais Médicos and a reduction of ESF coverage to 16% of the population. In the fourth, best-case scenario, both programs provide universal coverage.

In all modeled scenarios, including the worst-case scenario, projections indicate a reduction in mean premature mortality in Brazil through 2030 from a current baseline of 45 annual deaths per 100,000 population. The rate of decline, however, is slowed as healthcare spending is contracted. In the best-case scenario, with universal access to services available from both programs, mortality decreases to 38 deaths per 100,000 population in 2030. In the scenario with the harshest budget cuts, mortality declines more modestly to 43 deaths per 100,000 population. According to the study, the severest austerity scenario would result in 48,546 more premature deaths over the following decade compared with current levels of program coverage.

Rasella warns that the impact from reducing ESF coverage would be hardest on the poorest municipalities of Brazil. The researchers also note that premature death rates due to complications associated with infectious diseases and malnutrition would be 11.7% higher in the worst-case scenario compared with current coverage levels in these regions. “Shrinking ESF coverage would affect population groups that are the most vulnerable from a social and economic standpoint and have the worst mortality rates compared to the rest of the population,” says Rasella.

What is more, these projections capture only a portion of the effects from reduced spending on ESF and Mais Médicos—premature mortality accounts for only 10–15% of total deaths in Brazil. A 2018 study in PLOS Medicine by the UFBA group, using the same methodology, estimated that lower spending on ESF and Bolsa Família would result in 19,732 more deaths among children under 5 over the period to 2030.