In a June episode of the Mano a Mano podcast, Mano Brown and Thaíde talked about the changes they had seen in Pedreira, a neighborhood in the far south of São Paulo that the rappers both know well. “This place used to be really poor. Of course the keen eye of a sociologist would find tons of flaws there—we’re talking about a favela, after all. But for us, it is clear how the people there fought and prospered,” says Brown, the host of the podcast. The different ways people see poor urban areas, as alluded to by Brown, a member of the rap group Racionais MC’s, reflects a movement that has been growing in Brazil over the last 20 years and involves the incorporation of hip-hop—a social, political, and cultural movement that emerged in the USA in the 1970s—as a subject of study at Brazilian universities. As hip-hop turns 50, these forms of expression previously marginalized in academia are now coming to be seen as “sociohistorical explanations of how Brazil works,” according to anthropologist Waldemir Rosa of the Federal University for Latin American Integration (UNILA).

José Cruz/Agência Brasil

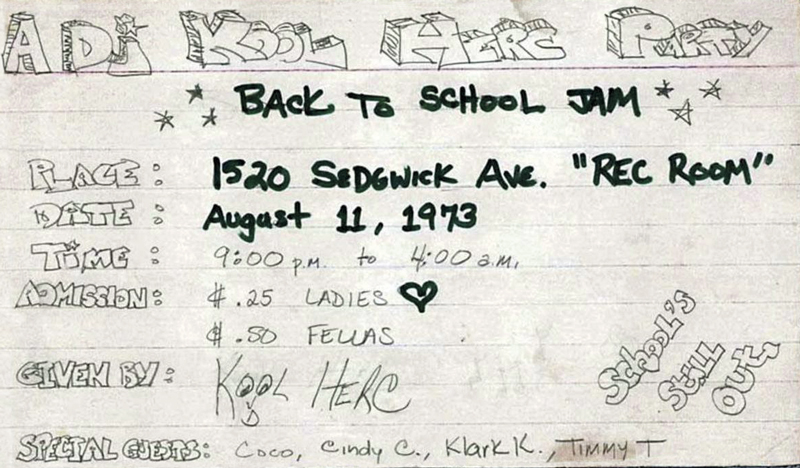

…and graffiti in São Paulo: as well as rap, hip-hop culture includes other forms of artistic expressionJosé Cruz/Agência BrasilHip-hop was born in New York City, in areas affected by poverty, violence, lack of infrastructure, and the illegal drug trade, home to much of the city’s Black and Latino population. A party thrown in the Bronx in August 1973, which featured music by Jamaican-American DJ Kool Herc, is considered the inaugural milestone of the movement. He is credited with inventing the “break,” introducing new sounds or changing the rhythm of songs using record-mixing equipment. At the same event, people began to improvise rhymes over DJ Kool Herc’s music, creating rap, an acronym for rhythm and poetry. In addition to music, hip-hop encompasses artistic expressions through graffiti, break dancing (a style of urban dance based on break beats), and others.

According to sociologist Daniela Vieira dos Santos of the State University of Londrina (UEL), hip-hop first emerged in Brazil with break dancing in the 1980s, inspired by American movies about the new form of dance, such as Wild Style (1972), directed by Charlie Ahearn, and Beat Street (1984), directed by Stan Lathan. During this period, members of the movement in the city of São Paulo, known locally as hip-hoppers, danced at parties called black balls. At the end of the 1980s, the events began being held at the São Bento subway station and on 24 de Maio Street in the city center, which became meeting points for people in the scene. “The first art form that reached the young participants of these black balls was break dancing, followed by rap. Just like in the USA, people in Brazil became involved in this cultural movement to escape the violence and danger of their urban lives,” explains UNILA’s Rosa.

Reproduction

Invitation to the party that gave birth to the hip-hop movement 50 years agoReproductionOf the various forms of artistic expression encompassed by hip-hop, it is rap that has had the greatest impact over the last five decades, due to how easy it is to share music, according to the UEL professor. The first albums from the genre recorded in Brazil were the compilations Hip hop cultura de rua (Hip-hop street culture; 1988) and Consciência black – Volume 1 (Black consciousness – Volume 1; 1988). The latter, released by the record label Zimbabwe Records, featured two tracks by Racionais MC’s, which was formed the same year by Mano Brown, Ice Blue, Edi Rock, and KL Jay: “Tempos difíceis” (Difficult times) and “Pânico na zona sul” (Panic in the South Zone). The same compilation also included the song “Nossos dias” (Our days) by Sharylaine. According to Vieira dos Santos, Sharylaine was the first woman to record a rap song in Brazil. It was around this time, according to the UEL professor, that the first hip-hop groups began to form in the city of São Paulo, spreading the principles of hip-hop culture, politically educating the poor urban youth, and suggesting ways to overcome inequalities. “Rap really consolidated itself as a musical genre in Brazil at the end of the 1990s, thanks in large part to the success of Racionais MC’s, considered the most important rap group in the country when they released the album Sobrevivendo no inferno [Surviving in hell; 1997]”, explains the sociologist.

Steven Ferdman / Getty Images

DJ Kool Herc in New York, 2019Steven Ferdman / Getty ImagesGabriel Gutierrez, a researcher from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), says that academic work on hip-hop flourished in the USA in the 1980s, often associated with the field of African studies, especially the sociology of culture. “It was a specific type of rap called Afrocentric rap, which has a strong political focus and was made famous by the duo Public Enemy, that propelled academic interest in hip-hop,” says Gutierrez, who has been studying the movement for around 10 years. According to the scholar, many of these Afrocentric rap groups were composed of the Black middle-class and university students from New York City. “They created protest music that many politicians and the police were unhappy about, but even so, they were absorbed by the cultural industry. These artists had contracts with major record labels, were invited to appear on television, and were constantly in the media,” he says.

In Brazil, the first academic papers on hip-hop were written in the 1990s. One pioneering paper was the doctoral thesis “Invadindo a cena urbana dos anos 1990 – Funk e hip hop” (Invading the urban scene of the 1990s – Funk and hip-hop), defended at UFRJ in 1998 by historian Micael Herschmann. He is now supervising Gutierrez’s postdoctoral fellowship at the same institution. One of the earliest works, according to musicologist Walter Garcia of the Institute of Brazilian Studies at the University of São Paulo (IEB-USP), was a doctoral thesis on rap in the city of São Paulo, completed at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) in 1998 by anthropologist José Carlos Gomes da Silva, who is now a professor at the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP). Another example is Elaine Nunes de Andrade’s master’s thesis on rap and education, written at USP’s school of Education (FE) in 1996. Garcia began studying rap based on the Racionais MC’s albums Raio X do Brasil (X-ray of Brazil; 1993) and Sobrevivendo no inferno (Surviving in hell; 1997) and after reading two issues of the magazine Caros amigos (Dear friends). The first featured a report on Mano Brown and the second was a special on hip-hop, based on the undergraduate work of anthropologist Spency Kmitta Pimentel, currently a professor at the Federal University of Southern Bahia (UFSB). “My intention was and continues to be to critique Racionais MC’s aesthetics in the context of a broader study of popular and commercial music in Brazil,” says Garcia. Holocausto urbano (Urban holocaust; 1990) was the group’s first record in a complete discography that consists of eight original titles and two compilations. The musicologist says that despite differences between the albums, “the artistic value of Racionais MC’s comes from the combination of musical merit and the topics addressed.” According to Garcia, musical merit is a mixture of several artistic elements: the choice of words, rhymes, figures of speech, narratives, the construction and interpretation of characters, musical accompaniment, balance, and more. And the topics addressed, which cover various forms of structural violence in Brazilian society, cause listeners to feel “not only sensations and affections, but also to critically reflect on the economic and social origins of the phenomenon.”

Luana Fischer / Folhapress

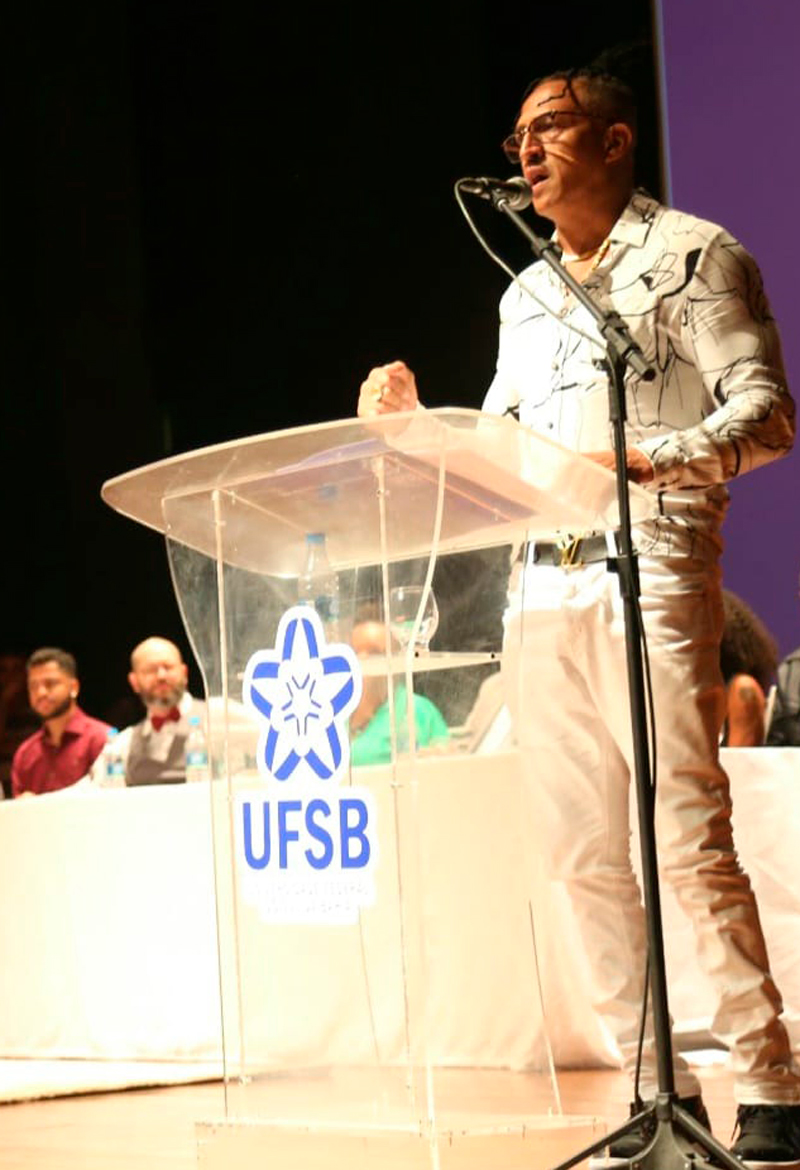

Thaíde and DJ Hum perform at a festival in São Paulo, 1999Luana Fischer / FolhapressRichard Santos, a sociologist from UFSB, points out that just as occurred in the USA, Brazilian television started broadcasting programs about hip-hop between the 1980s and 1990s, which sparked young people’s interest in researching the subject. Santos, also known as Big Richard, was once a promoter of the movement and other marginal cultures in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, in addition to directing and presenting television programs on various TV stations. Now vice dean of outreach and culture at UFSB, he was at the forefront of the process to award Mano Brown an honorary PhD in early November.

Hip-hop as a subject of study in academia has grown in part thanks to a Brazilian law (Law 10.639/2003) that establishes the mandatory teaching of African and Afro-Brazilian history and culture in education, according to Rosa, from UNILA. Boosted by the introduction of affirmative action in Brazilian universities—designed to encourage Black and other minority populations into academia—the first study in the 2000s sought to analyze the relationships between hip-hop and racial identities in fields such as sociology, history, and literature. Later, continues Rosa, hip-hop began to be studied by urban anthropology researchers, with a focus on youth and racialized identities. For his master’s degree, which he completed at the University of Brasília (UnB) in 2006, he investigated the construction process of young, Black, heterosexual, masculine identity in the lyrics of rappers from poor urban neighborhoods in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, the Federal District, Goiás, and other locations. During his PhD, defended at UFRJ in 2014, the anthropologist analyzed the relationships between hip-hop and the public authorities. “I found that organizations and associations sought to establish legal entities during the 2000s so that they could access public funding to promote cultural and community activities,” says Rosa. He adds that since 2010, as the movement has continued to gain ground in academia, hip-hop has begun to experience an epistemological turn, seen as a potential way of explaining the functioning and history of Brazilian society.

Rovena Rosa / Agência Brasil

A pioneering artist on the Brazilian scene, rapper Sharylaine in 2023Rovena Rosa / Agência BrasilThe introduction of hip-hop as a subject of study in academia is aligned with an increasingly intense institutionalization process of the movement. Break dancing, for example, is set to feature as an Olympic sport for the first time at the Paris Olympics in 2024. In Brazil, part of this trend is the establishment of state and municipal decrees recognizing hip-hop as a form of cultural heritage, as well as the creation of public funding streams, museums, and cultural centers. In October, the Brazilian Ministry of Culture (MinC) launched a R$6-million call for proposals designed to recognize and value hip-hop culture. In July, a law was passed (Law 7.274) that acknowledged the movement as a cultural and intangible heritage of the Federal District, and the city of Campinas in São Paulo State is currently preparing to issue a similar decree. The government of Rio Grande do Sul plans to inaugurate the Hip-Hop Culture Museum in Porto Alegre in December. The 4,000-square-meter space, situated in a former school and conceived by rapper Rafael Rafuagi, will bring together a collection of around 10,000 items, including instruments, record players, pamphlets, and other documents, collected from across the state of Rio Grande do Sul. “In addition, we have just presented a participatory inventory of hip-hop culture in each state of Brazil to the National Institute for Historical and Artistic Heritage [IPHAN] requesting that it be made heritage,” says Rafuagi. The aim of heritagization is to encourage the development of artistic and historical expressions through the appreciation and revitalization of certain cultures.

Arquivo Edgard Leuenroth / UNICAMP

Mano Brown on the cover of Brazil’s first hip-hop magazine in 1993Arquivo Edgard Leuenroth / UNICAMP“Hip-hop managed to legitimize itself in society despite historically facing prejudice,” says UNICAMP anthropologist Jacqueline Lima Santos, one of the organizers of Festival Internacional Hip Hop 50, held by the institution in November to celebrate the movement’s fiftieth anniversary. Together with Vieira dos Santos from UEL, Lima Santos manages an imprint focused on hip-hop publications at the publishing company Editora Perspectiva. In 2021, they translated the book Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America by American sociologist Tricia Rose into Portuguese. Originally published in 1994, the book was the result of pioneering research carried out on the subject in the USA. In 2023, they edited Racionais MC’s – Entre o gatilho e a tempestade (Racionais MC’s – Between the trigger and the storm), a compilation of studies and academic papers on the rap group written in Brazil in recent years. “Through these publications, activities at universities, and dialogue with artists from the scene, we want to expand the field of study on hip-hop in the country,” says Lima Santos. Vieira Santos, from UEL, believes studies need to delve deeper into issues such as female roles in the movement. “Women have been involved in hip-hop from the very beginning. But they generally remain on the sidelines, and many are made invisible,” points out the researcher.

Arthur Dantas Rocha, author of the book Racionais MC’s – Sobrevivendo no inferno (Racionais MC’s – Surviving in hell; Editora Cobogó, 2021), investigates how the group from São Paulo was received by the press and cultural sectors between the releases of the albums Raio X do Brasil and Sobrevivendo no inferno. “At the time, the records were already well-known and celebrated in poor urban areas, but elsewhere, there was a general distrust of rap, which was an undervalued musical genre,” says Rocha. “In fact, much of the discourse was clearly racist, with some wrongly stating that the members of Racionais MC’s were ex-convicts.” At the same time, he says, artists such as Caetano Veloso and Chico Buarque highlighted the value of the group’s work, in contrast to the views of the press.

Malu Carvalho / UFSB

Mano Brown receiving an honorary PhDMalu Carvalho / UFSBThe tone began to shift in the first decade of the 2000s due to various factors. One was that rap started a process of becoming more professional, with rappers like Emicida opening production companies dedicated to their artistic careers. In postdoctoral research funded by FAPESP and completed at UNICAMP in 2019, Vieira dos Santos, from UEL, identified that the musical genre began to occupy a new social and symbolic position in society following this professionalization process, constituting what she called “the new condition of rap.” Sociologist Felipe Oliveira Campos reached a similar conclusion in his master’s research, completed at USP’s School of Arts, Sciences, and Humanities (EACH) in 2019. “In the 1990s, rap shows were known for their dangerous conditions and were often delayed for hours. The producers helped change this,” says Campos. The 2022 documentary Racionais: Das ruas de São Paulo pro mundo (Racionais MC’s: From the streets of São Paulo to the world), directed by Juliana Vicente, addresses this topic. During his master’s degree, Campos researched the São Bernardo do Campo Church Rap Battle. Created in 2013, the event takes place weekly in front of the city’s central church, a place where workers held demonstrations during Brazil’s military dictatorship (1964–1985). More than a thousand people show up every week, many of them from municipalities in the São Paulo Metropolitan Area, who take part in rap battles and improvised rhyming.

Today, according to UFRJ’s Gutierrez, the rap music market is complex and multifaceted, covering everything from political to romantic music. “Despite this range, the poetics of these songs share a common element, in that they chronicle life on the street and in the neighborhoods where the artists live or grew up,” explains the researcher, who is now doing a postdoctoral fellowship in which he is investigating the rap market in Brazil, especially in Rio de Janeiro. The first rappers in the state were highly influenced by Miami bass, a form of rap that originated in Florida, USA. “The musical style is good to dance to and has Latin elements. It arrived in Rio in the 1970s, where it encountered samba, Candomblé, and Umbanda, later giving rise to Funk carioca and the early seeds of the hip-hop scene,” he says.

@cineastafavelado

Rapper performs at Batalha da Matriz in São Bernardo do Campo, São Paulo@cineastafaveladoIn Brazil, some researchers, such as psychologist Mônica Guimarães Teixeira do Amaral of USP’s School of Education, have used hip-hop as a pedagogical tool in schools. In research funded by FAPESP and completed in 2018, she found that many schools in São Paulo failed to comply with laws 10.639/03 and 11.645/08, which require Afro-Brazilian and Indigenous history and culture to be taught in schools. In the study, Amaral developed methodologies and strategies with which educational institutions could implement the legislated topics. By encouraging intersections between school culture, expressions of hip-hop, and shared teaching between artists and teachers, the researcher suggests working with content on African history, in addition to Afro-Brazilian and urban cultures, in elementary school curricula.

Rapper Daniel Garnet, who has a degree in physical education and is now a PhD student at FE-USP, also makes a similar recommendation. In his academic research, he created methodologies that use rap battles in pedagogical processes. Thus, in workshops given at USP, in public schools, and at Fundação Casa, he uses the musical genre to address verse metrics in poetry, rhymes, and figures of speech, as well as teaching classes on the history of Africa and Brazil. “Rap battles and break dancing occupy a special place in the minds of young people, who like challenges and testing their limits. Furthermore, they represent a combination of the arts and education, which means they can help awaken a student’s interest in other school subjects,” concludes Garnet.

Projects

1. The new generation of rap and cultural industry (nº 16/11769-1); Grant Mechanism Postdoctoral Fellowship Abroad; Supervisor Renato José Pinto Ortiz; Beneficiary Daniela Vieira dos Santos; Investment R$236,883.97.

2. The new generation of rap and cultural industry (nº 15/20592-5); Grant Mechanism Postdoctoral Fellowship in Brazil; Supervisor Renato José Pinto Ortiz; Beneficiary Daniela Vieira dos Santos; Investment R$531,558.12.

3. What rap says and schools contradict: A study on street art and youth on the margins of São Paulo (nº 16/06256-5); Grant Mechanism Research Grant ‒ Scientific Publications ‒ Books in Brazil; Principal Investigator Monica Guimarães Teixeira do Amaral; Investment R$4,000.

4. The ancestral and the contemporary in schools: Recognition and affirmation of Afro-Brazilian histories and cultures (nº 15/50120-8); Grant Mechanism Research Grant ‒ Public Policy Research; Principal Investigator Monica Guimarães Teixeira do Amaral; Investment R$195,977.72.

Scientific articles

GUTIERREZ, G. Rap de mensagem e conhecimento de oposição. A comunicação do 5E no hip hop e sua manifestação dentro do rap brasileiro. Revista Trilhos, vol. 3, no. 1. 2022.

SANTOS, D. V. A nova condição do rap. Estudos de Sociologia, vol. 27, pp. e022005–21. 2022.

ROSA, W. A nação como narrativa masculina: As construções nacionalistas do gênero e a fala das mulheres no rap brasileiro entre 1,990 e 2,005. Humanidade & Inovação, vol. 7, p. 106. 2020.

Books

VIEIRA, D. & SANTOS, J. L. (orgs.). Racionais: Entre o gatilho e a tempestade. São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva, 2023.

ROCHA, A. D. Racionais MC’s – Sobrevivendo no inferno. São Paulo: Editora Cobogó, 2021.

AMARAL, M. G. T. O que o rap diz e a escola contradiz: Um estudo sobre a arte de rua e a formação da juventude na periferia de São Paulo. São Paulo: Alameda/FAPESP, 2016.