Universities in many countries are searching for new ways to improve access to scientific literature, having suspended expensive and potentially abusive subscription contracts with major publishers. In order to at least partly meet the information needs of their students and researchers, institutions are increasingly turning to libraries and social media networks to obtain restricted content, as well as using tools that help locate articles available through open access. The University of California (UC), USA, for example, announced in February that it was ending its US$11-million-per-year contract with Dutch publisher Elsevier, through which its 273,000 students and 68,400 professors and researchers were able to access papers from 2,400 journals. Responsible for around 10% of all scientific output in the USA, UC had been trying to secure a new agreement with Elsevier that would have covered all charges paid by its researchers to make articles available via open access as well as the annual subscription fees. Elsevier insisted on maintaining the traditional setup for most of its journals, charging subscription fees and article publication charges separately, including extra fees when the author wants to publish their paper freely online.

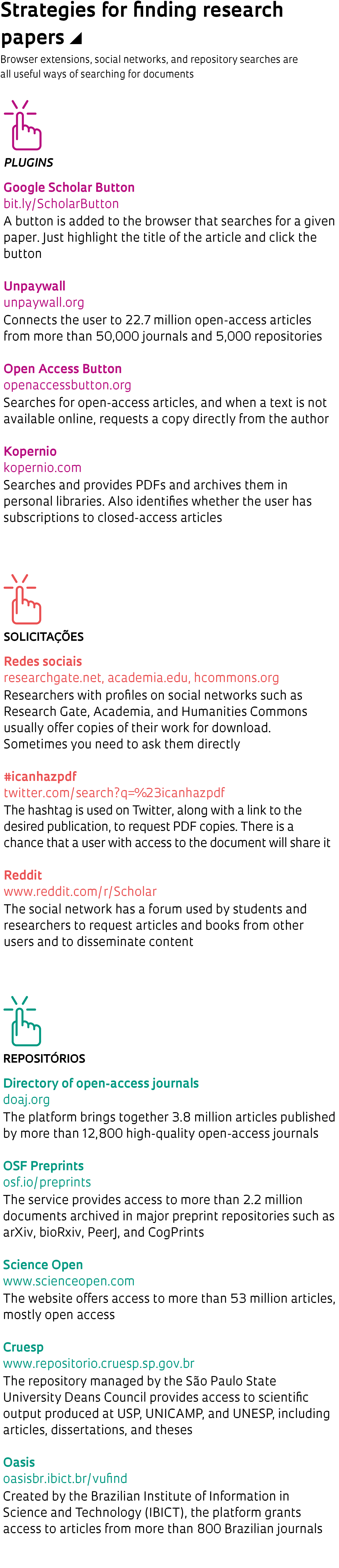

With access to so many journals now blocked, UC has created a webpage advising its students and researchers of a number of alternative options. The suggested strategies include searching for papers in academic databases such as Google Scholar and PubMed, and the use of browser plugins designed to locate PDF copies of scientific articles. If these steps are not enough, the institution recommends asking UC campus libraries, which are members of networks through which articles and books are shared, or using academic social networks, where people can request papers directly from the authors. “I fully support our faculty, staff, and students in breaking down paywalls that hinder the sharing of groundbreaking research,” said Janet Napolitano, the university’s president, in a statement.

The approach taken by UC is not unique. Recently, higher education institutions in Germany, Sweden, and Norway have also decided not to renew journal subscriptions with Elsevier and have adopted similar alternatives. “These digital tools have given universities unprecedented bargaining power,” says Abel Packer, coordinator of the SciELO Brazil open-access academic library. “In the past, canceling subscriptions would have been impractical, making the work of researchers impossible. Today, universities have other options.” The movement gained even greater momentum in September last year when the European Union and research funding agencies from 14 countries launched Plan S, an international initiative that aims to provide immediate open access to all articles based on publicly funded research from 2020.

Using search engines is sometimes all it takes to locate the PDF of an article—if it is available, of course. In recent years, a number of free digital tools have emerged that make this task even simpler. One of the most popular is the Google Scholar Button, a plugin that gives access to Google Scholar content and helps locate texts available online and in university libraries. Users simply highlight the title of the document on the page they are visiting and click the button to find the full paper.

There are other extensions with similar features, such as the Open Access Button, developed by a UK group linked to a network of libraries that promote open-access publishing. The plugin has another important function: if the article is not available anywhere online, a request is sent directly to the author. Maintenance and updates to the Open Access Button have been funded over the past two years by a US$420,000 grant from Arcadia, a philanthropic fund run by Peter Baldwin, a philanthropist and professor of history at the University of California, Los Angeles. “These tools are totally legal and well-intentioned. But their results are always limited, because there is a lot of research that is not published via open access,” says Moreno Barros, a librarian at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) with a PhD in the history of science.

Another successful example is Unpaywall, a free service created in the US that gives access to 22.7 million preprint papers and manuscripts available through open access, as well as paid-access articles that have copies legally stored in institutional repositories. According to ImpactStory, which created the tool, it reached 200,000 active users in February. It may not be the solution to all of a researcher’s demands, but it works almost half of the time while still respecting copyright: a 2017 survey of searches made by Unpaywall users found that 47% of papers were available for free somewhere online. “We’re setting up a free lemonade stand right next to the publishers’ lemonade stand,” said information scientist Jason Priem, who launched the service in partnership with Heather Piwowar, a researcher at the University of Pittsburgh, USA, according to The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Lou Stejskal / Flickr

Geisel Library at the University of California, San Diego: the institution’s contract with publisher Elsevier cost almost US$11 million per year

Lou Stejskal / FlickrThe appeal of these tools is clear: it is not always easy to find an article, even when it is available through open access. Locating a paper published by a journal that offers all of its content freely online is one thing—a simple internet search is usually all it takes, in these cases—but finding a free copy in an institutional repository of a text originally published in a closed-access journal is a much greater challenge. These repositories are often not well indexed on search engines. This is a situation frequently faced by students and researchers, and plugins facilitate access by cataloging multiple sources.

In February, FAPESP updated its open-access policy, which was created in 2008 and resulted in the formation of the São Paulo State University Deans Council Scientific Repository (CRUESP) in 2013, where articles, theses, dissertations, and other scientific papers published by researchers from the University of São Paulo (USP), the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), and São Paulo State University (UNESP) are archived. The changes mean that articles resulting wholly or partly from research funded by FAPESP must be disseminated in journals that allow a copy of the manuscript to be stored in a public online repository, openly accessible to all.

The copy should be archived as soon as the paper is approved for publication or after the embargo period established by the journal—usually between six months and a year. Researchers are free to choose which journals they want to publish their articles in, but they are advised to select titles that allow a copy to be stored in a repository. To find out what model each periodical uses, they can consult the Sherpa-Romeo website, created by a group of research universities in the UK to provide information on the open-access rules adopted by different publishers and scientific societies.

Despite being available through open access, articles archived in repositories are not always easy to find

Some journals prohibit copies of published articles from being archived, but allow it for versions of the text that have not yet undergone peer review. The Kopernio browser plugin also indexes preliminary papers. According to its creators, it is able to find 70% of the manuscripts searched for by users. The service was created by a startup that was acquired in 2018 by Clarivate Analytics, which manages the Web of Science database. It utilizes artificial intelligence algorithms and can also be used by people with subscriptions to closed journals. Users create an account with the plugin, stating whether they are affiliated with any institution or a subscriber of any journal. Kopernio then saves their access rights and automatically includes in its searches content from closed journals to which they subscribe. This function can be useful, according to the creators, for those who have legitimate subscriptions provided by their institutions but use illegal search tools just because they are quicker and easier. “Many researchers use pirate sites not out of necessity, but because it’s more convenient,” Jan Reichelt, one of the founders of Kopernio, told the magazine TheBookseller. One of the websites he was referring to was Sci-Hub, a repository that provides access to illegally obtained copies of 64 million scientific articles. Prior to founding Kopernio, Reichelt was one of the founders of Mendeley, an academic reference management tool that later became a social network for researchers and was purchased by publisher Elsevier in 2013.

Social networks can also play an important role in the search for scientific articles. Researchers with profiles on Research Gate, Academia, Mendeley, and Humanities Commons regularly offer copies of their work for download. It is also possible to directly message an author asking for a copy of an article. Other strategies, such as the #icanhazpdg hashtag used on Twitter, are less effective and do not guarantee that copyright law is respected. Researchers tweet the hashtag along with the URL of the desired paper and hope that another user with access to the document will share it. Reddit also has a forum specifically for requesting and providing copies of articles and books.

According to Abel Packer, from SciELO, sharing articles online has become a modern version of the interlibrary loan—before the advent of the internet, researchers looked for articles and books in libraries and obtained paper copies from partner institutions. “Today this is done through social networks. When I need an article that is difficult to access, I ask someone who already has it,” he says. In some situations, legal boundaries are crossed, but that line has become blurred in scientific communication, Packer notes. A study published by Unpaywall’s Hepay Piwowar 2017 showed that 58 percent of articles freely accessed online were from closed-access journals and were made available by publishers themselves, without formal permission to do so. “Publishers end up playing both sides, because they do not want to lessen the chance of articles from their journals being cited and creating an impact,” he explains.

Republish