It is hard to think of the Amazon rainforest and not imagine a vastness of green. It is home, however, to much more than can be seen from the sky. Giant geometrical figures hidden by the canopies are being identified using the optical technology LIDAR (Laser imaging detection and ranging), as an article published in October in the journal Science showed. In September, an article in Science Advances also provided more evidence that terra preta [literally meaning black soil and also known as Amazonian dark earth], generally considered the work of pre-Columbian peoples, was intentional and not the result of chance.

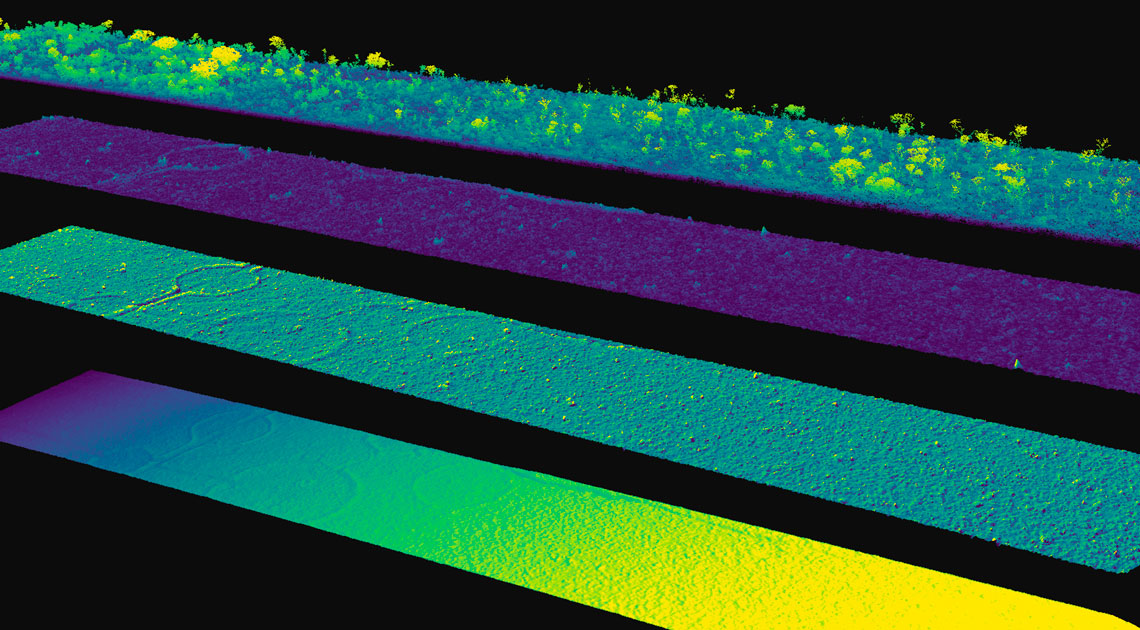

Research carried out in the last three decades indicates that Brazil was already widely inhabited, including in the Amazon region, prior to the arrival of Portuguese colonizers in 1500. The scale of this Amazonian occupation is now growing, based on mapping done with equipment fitted to a drone or onboard an aircraft, which emits thousands of laser pulses per second and, with each pulse, calculates a measurement of distance. “It’s almost like a radiography,” explains geographer Vinicius Peripato, a PhD student at the National Institute for Space Research (INPE) and lead author of the study also coauthored by 230 researchers.

In already deforested areas in the western part of the Amazon, it is possible to observe enormous geometrical figures, the geoglyphs, formed by ditches dug in the ground. Since the turn of the millennium, with the Google Earth tool, they have become visible through the use of satellite imaging. “It was possible to identify hundreds of these structures, especially in the west of the Amazon,” says biologist Luiz Aragão, head of the INPE’s Earth Observation and Geoinformatics Division, advisor to Peripato, and coordinator of the article in Science.

In the last 20 years, excavations carried out by archaeologists have shown that the geometric forms were important religious sites (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 186). Peripato and his colleagues knew of the existence of these traces of human occupation and thought that more of them may exist beneath the forest canopy. “Previous tests had indicated the possibility of the occurrence of these structures, but nothing precise,” he explains.

They then developed a method to virtually remove the forest and improved the detection of aspects of relief—the resolution of the LIDAR sensing data was still not suitable for archaeological observations. The equipment covered 5,315 square kilometers (km²) of the Amazon, equivalent to 0.08% of the forest. “It worked, luckily we found 24 previously undiscovered structures,” celebrates Peripato.

Vinicius Peripato / INPE

The optical technology LIDAR enables layers below the forest to be seen as if it were a radiography that reveals subtle variations in relief, such as the geoglyphsVinicius Peripato / INPEPleased with the discovery, the researcher developed a mathematical model to estimate how many and where other similar geoglyphs would be on the territory, taking a series of still-unknown variables into account. He compared the data provided by the LIDAR sensor with information from another 937 known archaeological structures and, using this model, calculated that at least 10,272 still undiscovered pre-Columbian structures exist, possibly reaching 23,648 in the entire forest—a territory of 6,700 km². The distribution of 53 species of domesticated plants used for food was mapped in previous forestry inventories and may serve as an indication of the existence of archaeological structures in the vastness of the Amazon.

“It was a study that required a multidisciplinary team and the use of cutting-edge technology to carry out,” assesses Aragão. Dating of the still-undiscovered geoglyphs was estimated based on already existent archaeological literature, but can only be confirmed when there is excavation work and the collection of material for analysis.

“It’s an important article that confirms something that archaeologists have said for years: there were lots of people living in the Amazon in the past,” comments archaeologist Eduardo Góes Neves, of the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology of the University of São Paulo (MAE-USP). “These peoples lived there and they also modified the forest,” he states. Evidence of human presence in the region dates back around 12,000 years. For a portion of the experts, the Amazon is a biocultural heritage that suffers influences from both nature itself as well as from the population that lived and still lives there.

Neves says that a large part of the still-preserved geoglyphs are on environmentally protected lands, of Indigenous occupation. “It is the Indigenous peoples who preserve the structures in the midst of the agribusiness advance and the destruction taking place in the Amazon,” he remarks. In his view, the Indigenous presence is very ancient and contributed to creating the country’s biomes. “You cannot separate their history from the history of Brazil.”

Diego Lourenço Gurgel

With LIDAR and the mathematical model, the researchers calculate that there are between 10,000 and 24,000 of these structures in the AmazonDiego Lourenço GurgelThe terra preta found in various points of the Amazon is another sign of agricultural activity registered around the geoglyphs and that has helped to give shape to the biomes. Made up of leftover foods, such as cassava and fish, ashes, and other organic waste from the forest, it is rich in nutrients such as phosphorous, calcium, magnesium and nitrogen, essential for cultivating food.

“When terra preta began being studied, it was a revolution in Amazon archaeology: providing evidence of the existence of large populations on that land, because to form that material, it is necessary to have many people for a long time in the same place,” states British archaeologist Jennifer Watling, of the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology of the University of São Paulo (MAE-USP), coauthor of the article. Prior to these studies, the general understanding was that the Amazon rainforest could not support a very dense population due to the lack of fertile soil, she says. “The terra preta shows that it is possible to support many people without destroying the forest.”

The team collected over 3,600 soil samples from four archaeological sites, two historic villages, one modern village in the Alto do Xingu region called Kuikuro II and some samples from the Alto Tapajós region, and from the Carajás Mountains. The analyses revealed that the oldest samples are over 5,000 years old.

The dating of the terra preta is one of the main controversies from the latest studies made with this type of soil. In 2021, an article in the journal Nature Communications questioned the anthropic origin of terra preta. “Based on elemental analysis, the data does not match with the presence of human beings in the Amazon,” states agricultural engineer Rodrigo Studart Corrêa, a specialist in the recovery of soils and a researcher from the University of Brasília (UnB). According to the study by Corrêa, the cultivation of Amazonian land dates back at least 4,500 years, although archaeological evidence points to practices of cultivation in the region 9,000 years ago.

For the agricultural engineer’s group, the terra preta they studied originates from sediments from the Andes mountain range. “This material is a river meander,” states Corrêa. According to him, based on the isotope analysis of strontium and other chemical elements, part of the composition of the samples does not come from organic matter. “The fragments of ceramic in these soils are the great mystery, but this could indicate that they were used to bury the dead, maybe because they were easier to dig,” he speculates.

Morgan Schmidt / UFSC (Image Provided by the Kuikuro Indigenous Association of Alto Xingu)

A Kuikuro woman deposits ash from a fire in an area where terra preta developsMorgan Schmidt / UFSC (Image Provided by the Kuikuro Indigenous Association of Alto Xingu)Schmidt and Watling, however, consider that their results refute this interpretation of an accidental formation of terra preta by local communities. The researchers carried out interviews with inhabitants, observed the daily life of the villages and saw the residents deposit fish and cassava waste in trash cans as tall as 60 centimeters in height. “The majority of the terra preta forms in waste disposal areas, as if it were compost,” says Watling. “They mix the organic material with ash and charcoal to form a fertile soil and spread it on the areas of cultivation.”

Terra preta is rich in pyrogenic carbon, also called charcoal or biochar, which originates from the burning of organic material and is nutritious for the plants. The study published in Science Advances revealed concentrations of carbon two times greater in the residential areas than in those less occupied. This happens because the Indigenous people use ash from domestic fires for the production of terra preta, according to geographer and archaeologist Morgan Schmidt, from the Laboratory for Interdisciplinary Studies in Archaeology of the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC), who has been studying the agricultural practices of Amazonian peoples for over 20 years.

Another advantage of this type of soil is the sequestration and storage of atmospheric carbon. The measurements point to around 4,500 tons of this element in one of the archaeological sites, while in the modern villages there is 110 tons. This shows how, over time, the carbon has persisted and accumulated. But climate change is a concern. “Carbon can decompose quicker due to the warming of the ground,” explains Schmidt. “We also saw that when there is deforestation in an area with terra preta and cultivation, the organic material is lost from the soil and the carbon returns to the atmosphere,” he points out.

The climate crisis could, equally, affect the consumption habits of the Indigenous populations that still prepare terra preta on their lands to this day. “This earth is created by means of a very particular way of using and managing the domestic space, which includes the disposal of leftover traditional foods such as cassava,” says Watling. “If they stop planting and consuming such foods, we don’t know if the terra preta would still form in the same way.”

Projects

1. Transition to sustainability and the water, energy, and food security nexus: Exploring an integrative approach with case studies in the Cerrado and Caatinga biomes (nº 17/22269-2); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Program FAPESP Global Climate Change Research Program; Principal Investigator Jean Pierre Ometto (INPE); Investment R$3,414,563.06.

2. Ten-year modeling of gross carbon emissions from forest fires in the Amazon (nº 18/14423-4); Grant Mechanism Postdoctoral fellowship; Supervisor Luciana Vanni Gatti (INPE); Beneficiary Henrique Luis Godinho Cassol; Investment R$664,726.13.

3. Exploring the risk of savanna expansion in tropical South America due to climate change (nº 16/25086-3); Grant Mechanism Postdoctoral fellowship; Supervisor Rafael Silva Oliveira (UNICAMP); Beneficiary Bernardo Monteiro Flores; Investment R$287,363.70.

Scientific articles

PERIPATO, V. et al. More than 10.000 pre-Columbian earthworks are still hidden throughout Amazonia. Science. Online. Oct. 6, 2023.

LEVIS, C. et al. How People Domesticated Amazonian Forests. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. Online. Jan. 17, 2018.

SCHMIDT, M. J. et al. Intentional creation of carbon-rich dark earth soils in the Amazon. Science Advances. Online. Sept. 20, 2023.

SILVA, L. C. R. et al. A new hypothesis for the origin of Amazonian Dark Earths. Nature Communications. Jan. 4, 2021.