Upon arriving in Nagasaki, Japan, on December 9, 1874, after a 48-day journey by ship, astronomer and engineer Francisco Antonio de Almeida Júnior (1851–1928), born in Rio de Janeiro, described the rare sight of Venus passing in front of the Sun as follows: “Shortly past 10 a.m., we witnessed Venus’s triumphant entry into the solar regions. It had been more than a century since the beautiful goddess had deigned to allow mortals to witness her ardent visits to the king of the stars.” This account is part of his book Da França ao Japão: Narração de viagem e descrição histórica, usos e costumes dos habitantes da China, do Japão e de outros países da Ásia (From France to Japan: Travel narration and historical description, uses, and customs of the inhabitants of China, Japan and other Asian countries), published in 1879.

Considered the first Brazilian astronomer to witness a transit of Venus and the first Brazilian citizen to visit Japan, Almeida joined one of the French teams, as he had been studying in Paris since 1872. An Italian team had gone to India, a French team to New Zealand, and a British team to Hawaii, all with the same goal: to improve solar parallax values. This term “indicates a change in the visible position of the star to which it refers,” explained Almeida Júnior in the book A paralaxe do Sol e as passagens de Vênus (The parallax of the Sun and the transits of Venus), published in 1878. In other words, it is the visible passage of the celestial object—in this case, Venus—over the solar disk, seen from different points on the globe.

WikidataCover of Almeida’s book with descriptions of the 1874 transit of Venus and predictions for the next one in 1882Wikidata

With data on the planet’s movement over the solar disk, astronomers calculated the distance between the Earth and the Sun, the so-called astronomical unit. “They were searching for more accurate values for Solar System dimensions,” explains astronomer Rundsthen Nader, of the Valongo Observatory at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), who studied Brazil’s participation in the 1874 and 1882 transits of Venus in his doctoral dissertation, completed in 2015.

The 1874 phenomenon was the eighth recorded, on the trail blazed by British astronomers Jeremiah Horrocks (1618–1641) and William Crabtree (1610–1644). Separately, from their homes near Preston and Manchester, both in the United Kingdom, they were the first to record a scientific observation of Venus passing in front of the Sun, on December 4, 1639.

“These observations were flawed and Harrocks and Crabtree didn’t even try to determine the Sun’s parallax,” says astrophysicist Oscar Matsuura, retired professor at the University of São Paulo (USP) and coordinator of the book História da astronomia no Brasil (History of astronomy in Brazil; Cepe, 2014). “Later, based on the angular diameter [apparent diameter, measured from Earth, in degrees] of Venus, Harrocks estimated the distance from the Sun to be 97 million km [kilometers], indicating that the Solar System was much larger than was believed at the time.” Paris-based Italian astronomer and mathematician Giovanni Cassini (1625–1712) and his assistant Jean Richer (1630–1696), based in Cayenne, French Guiana, observed the parallax of another planet, Mars, and obtained, in 1682, the first reliable measurement for the astronomical unit, 138 million km, which lasted for nearly a century.

Observing the passage—or transit—of Venus and Mercury, the two planets closest to the Sun, was then one of the main means of calculating the distance from Earth to our nearest star. Mercury passes in front of the Sun around 13 or 14 times every century, while the transits of Venus occur in 243-year cycles, starting with the first transit in December; eight years later, again in December, there is a second; there is a gap of 121.5 years until the third, in June; eight years later, also in June, there is a fourth transit; the next takes place 105.5 years later, also in December.

The idea of using a planet’s transit to calculate the distance between the Earth and the Sun was proposed in 1716 by British astronomer Edmond Halley (1656–1742), after witnessing a transit of Mercury in 1677 on the island of St. Helena. His hypothesis was that it would be possible to calculate the distance from the Earth to the Sun using triangulation, measuring the transit of another planet using specific points on Earth. “The transit of Mercury was more difficult to observe because its trajectory was just above the horizon. So, at that time, Venus was the best option,” says Nader.

WikidataThe French team in Paris, before traveling to Japan, with Janssen (seated, with a beard) and Almeida (standing, in a light suit)Wikidata

In one chapter of the book Epistemología e história de la astronomía (Epistemology and the history of astronomy; University of Córdoba, 2023), physicist Maria Romênia da Silva and André Ferrer Pinto Martins, both of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), note that Almeida was a key figure in Brazilian astronomy at the time and “embodies the desire and commitment of a generation of intellectuals interested in better understanding the country, with visions of advancement based on European standards.”

Almeida arrived in Paris in 1872, with a colleague from the Imperial Observatory of Rio de Janeiro, astronomer Julião de Oliveira Lacaille (1851–1926), both of whom had been granted scholarships by Dom Pedro II (1825–1891). “Until that time, utilitarian astronomy prevailed in Brazil, which served to determine timetables and to help with geographical measurements for road construction, while in Europe researchers were already trying to understand the chemical composition of stars,” observes Nader.

The changes in Brazilian astronomy began a year earlier, in 1871, when the emperor invited French astronomer Emmanuel Liais (1826–1900) to head the Imperial Observatory of Rio de Janeiro. Liais accepted, under two conditions: the institution would no longer focus on training students from military academies and would invest in astronomical research, including basic science. “There’s no denying that the emperor laid the groundwork for Brazil to play a major role in the international effort to observe the transit of Venus in 1882,” Matsuura points out.

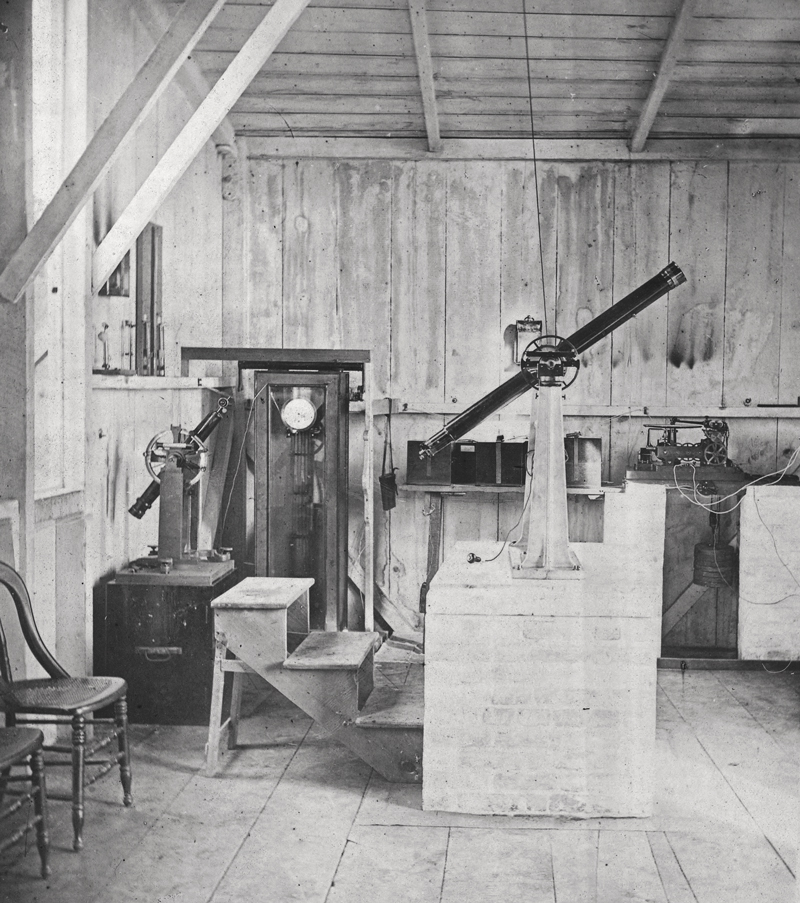

United States Library of Congress Equipment used by the Brazilian team to observe the transit of Venus on Saint Thomas Island, in the Antilles, in December of 1882United States Library of Congress

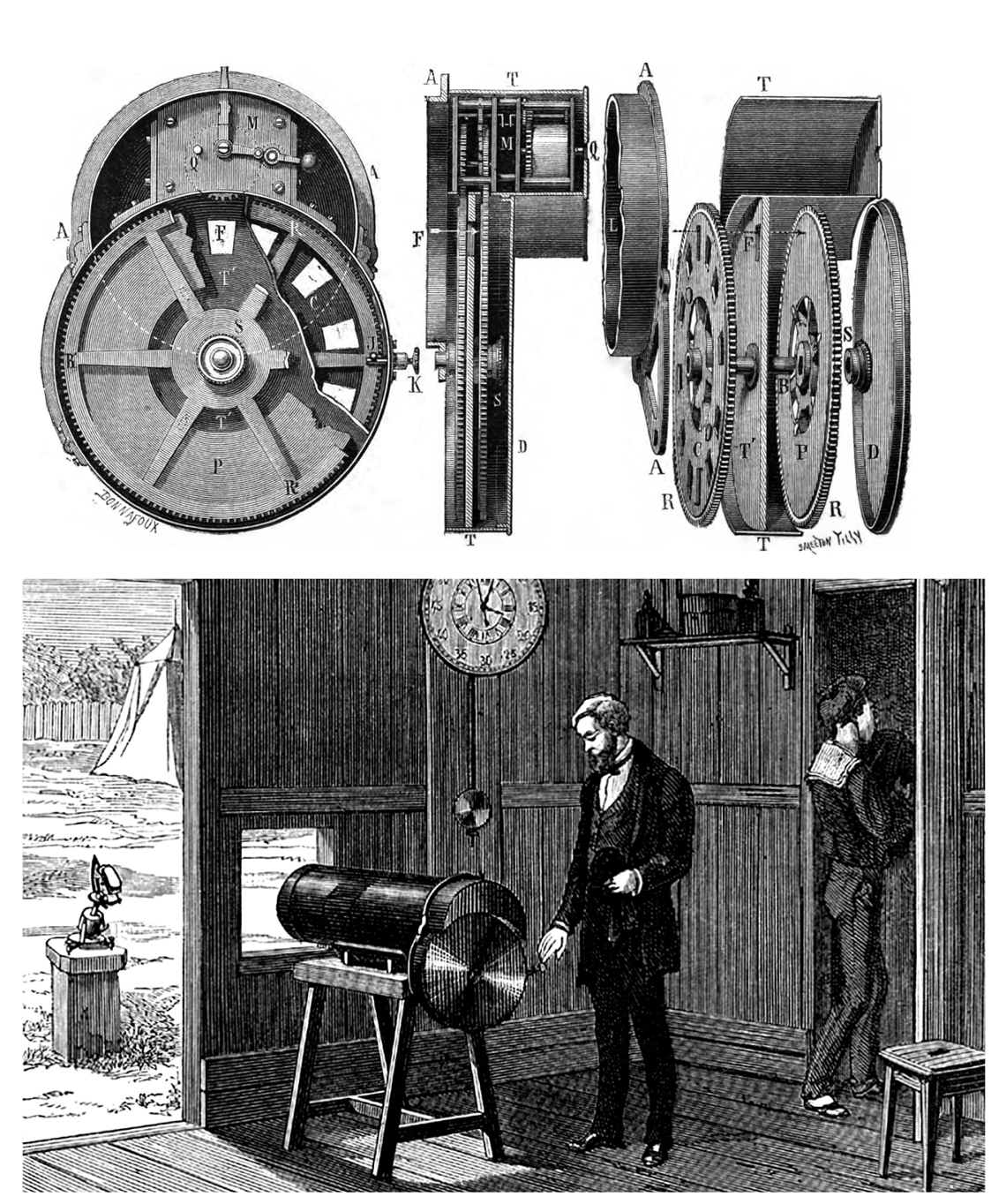

In Nagasaki, Almeida Júnior operated an innovative piece of equipment, the photographic revolver, developed by the leader of the French team, astronomer Pierre Jules Janssen (1824–1907). The device worked like a rudimentary camcorder and was used to record images of the moment Venus touched the solar disk, sequentially, with very short time intervals, on glass plates with silver emulsion. The result, however, was not as expected. “The images were grainy, which prevented a thorough analysis of the planet’s position,” says Nader. “The French team’s mission in Nagasaki contributed very little to improving the solar parallax. Overall, the data from 1874 hardly differed from what was already available.”

In 1875, still in Europe, Almeida received the Brazilian honor of Knighthood from the Imperial Order of the Rose for his participation in the French scientific committee and returned to Rio de Janeiro the following year as a Doctor of Philosophy from the University of Bonn, in Germany. “His dissertation focused on air movement, inspired by the fact that he had escaped unscathed from a typhoon that left around 8,000 dead in the city of Hong Kong when he was traveling through Japan with the French Committee,” says Silva.

Brazil made much more relevant observations of the 1882 transit of Venus, this time visible in South America, Central America, and eastern North America. One team was stationed at the Imperial Observatory, now under the lead of Belgian astronomer Luiz Cruls (1848–1908), and others went to Olinda, in Pernambuco, Punta Arenas, in Chile, and Saint Thomas Island, in the Antilles.

The cost of these expeditions spurred debates about funding for science in the country. “In 1874, there was some criticism about sending an astronomer to Japan, but on a much smaller scale,” recalls historian Jacques Pinto, of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation’s Oswaldo Cruz House (FIOCRUZ). This time, the Imperial Ministry and the Navy Ministry requested 30 contos de réis each to manufacture telescopes, build observation stations, pay researchers, and provide transportation.

JANSSEN, J. Bulletin de la Societé de Photographie. 1874 | FLAMMARION, C. La NatureThe photographic revolver disassembled (above) and in use by Almeida in NagasakiJANSSEN, J. Bulletin de la Societé de Photographie. 1874 | FLAMMARION, C. La Nature

Deputies and senators from the Liberal and Conservative parties voted together against releasing the funds. “There was a prevailing utilitarian view, where science should only be used for farming and agronomy,” notes historian Alexandra Aguiar, of Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ), who examined the political debate in an article published in August of 2017 in the journal Temporalidades. Finally, on May 30 of 1882, only the Imperial Ministry’s request was approved. Private donations provided the remaining funds for the Antilles mission, led by Antônio Luís von Hoonholtz, the Baron of Teffé (1837–1931).

Cruls headed the Punta Arenas committee and published the Brazilian observations in December of 1887 in Annales de L’Observatoire Impérial de Rio de Janeiro (Annals of the Imperial Observatory of Rio de Janeiro). According to Nader, the final value for the solar parallax obtained by the Brazilian committee was 147,826,661 km, because Cruls did not include the errors associated with the measurements, as the expeditions from other countries did. “In academic circles, the Brazilian committee’s results were well received,” says Nader.

Lacaille, who also studied in France, led the team stationed at an observation point in Olinda, but there is no record of Almeida Júnior’s participation in any of the 1882 Brazilian expeditions. His absence “seems inexplicable to this day, even considering the opinions of some astronomers who didn’t believe in the advantage of observing the transits of Venus to determine the solar parallax,” commented astronomer Ronaldo Rogério de Freitas Mourão (1935–2014), of the Museum of Astronomy and Related Sciences (MAST), in a 2005 article in Navigator magazine.

Upon analyzing all 94 pages of the book A paralaxe do Sol (The solar parallax), Silva discovered that Almeida indicated the times when Venus would probably be visible in cities throughout Brazil, Chile, Peru, the United States, Canada, France, and Scotland in 1882. “He implies that he was hoping to be invited to join the Brazilian committee,” she concluded. In her opinion, political tensions of the time could explain why he was sidelined: “He aligned himself with liberal ideologies, and the political atmosphere in 1882 was complicated for Dom Pedro II, as the disputes over funding the scientific committees had already indicated.”

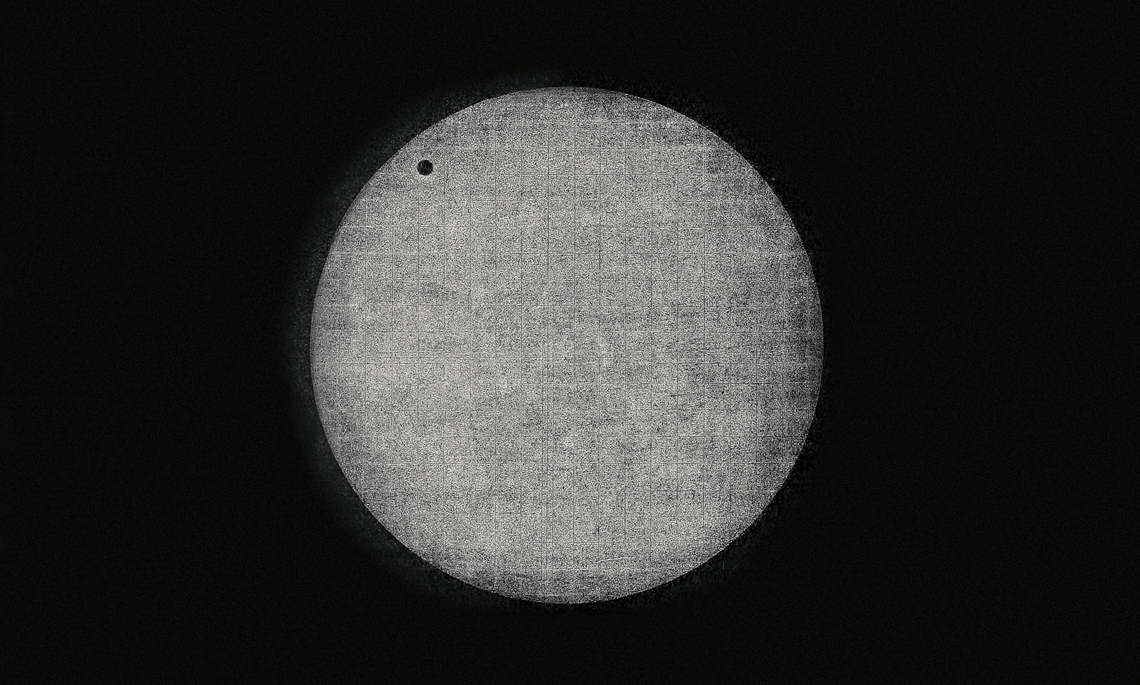

Wikimedia Commons | Gestrgangleri / Wikimedia Commons | Nasa / Wikimedia CommonsWith increasing precision, the transits of Venus in front of the Sun on December 6, 1882, August 6, 2004, and June 5, 2012Wikimedia Commons | Gestrgangleri / Wikimedia Commons | Nasa / Wikimedia Commons

Appointed director of the Diário Oficial (Official Gazette) in July of 1891, Almeida was removed from office six months later when President Deodoro da Fonseca (1827–1892) resigned. He was later imprisoned under President Floriano Peixoto (1839–1895) on charges of taking part in a conspiracy against the government in April of 1892. “He was critical of the First Republic’s military governments, which were known for being authoritarian,” Pinto comments.

At the end of the nineteenth century, instead of waiting for other transits of Venus, astronomers began calculating the solar parallax using asteroids, rocks of various sizes that orbit the Sun. Then, they used radar and the speed of light. In 1976, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) established the distance between the Sun and the Earth to be 149,597,870 km.

In 2008 and 2012, Venus passed the solar disk once again. “But these transits didn’t add much more information about these measurements. Just like eclipses, they are now mainly media events, which help to publicize science,” says Nader. The most easily visible planet in the sky should be in front of the Sun again on December 10, 2117, and December 8, 2125.

Republish