Brazil found a new dinosaur species in December. The animal was the size of a chicken, walked on two legs, and had long, fine hairs covering its body—a crude form of feathers—in addition to two pairs of an elongated, rigid structure protecting it from its shoulders in a V formation. It is estimated that the Ubirajara jubatus, as it was first called, lived about 120 million years ago where today is the Brazilian Northeast, feeding on insects and small vertebrates. The description of this rare dinosaur specimen of the Early Cretaceous, a geological period from 146 million years to 100 million years ago, is contained in a study published in the magazine Cretaceous Research by an international team of researchers. The discovery arose out of analyses of fossils from the Araripe basin, on the border of the states of Ceará, Piauí, and Pernambuco, one of the regions with a higher number of reported cases of trafficking of these materials in the country. The holotype—a single type specimen upon which the description of a new species is based—is in the State Museum of Natural History Karlsruhe in Germany, which attracted the attention of Brazilian researchers. They suspect that the fossil was illegally removed from Brazil.

The suspicion generated significant attention on social media. Dozens of scientists worked together to demand the return of the material. Amidst the criticism, and on the request of the Brazilian Society of Paleontology (SBP), Cretaceous Research took the article offline until the issues that had been raised were addressed. The case reached Federal Prosecutors (MPF) of Juazeiro do Norte in Ceará, who established a procedure to investigate the removal of the fossil and requested that German authorities seize and repatriate the material. One of the authors of the study, British paleontologist David Martill, of the University of Portsmouth in the United Kingdom, fended off accusations of international trafficking. “The holotype is in the Karlsruhe museum where I saw it for the first time. I did not take it and certainly did not export it,” he said to Pesquisa FAPESP. “No matter what happened, I am not responsible for verifying the origin of the fossils I work with. If they are in a museum, I presume they are there legitimately.”

To certify the legality of the holotype for Cretaceous Research, German paleontologist Eberhard Frey, curator of the Karlsruhe museum and author of the article along with Martill, presented a document submitted and signed in 1995 by José Betimar Melo Filgueira, then head of the regional office of the National Department of Mineral Production (DNPM) in Crato, Ceará, authorizing the “transport of two boxes containing limestone samples with fossils, without a market value and with the primary objective to undertake paleontological studies.” However, paleontologist Aline Ghilardi, from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), contests the document. “It does not talk at all about permanently exporting the materials abroad and it also does not specify how many and which fossils were in those boxes. The way it was written, the authors can continue to describe new species for the next 20 years, alleging that all of the holotypes came from them,” she says. She also calls attention to the fact that the employee who sent the authorization was charged in 2015 for administrative misconduct involving illegal submission of authenticity certificates for precious stones. “This ‘authorization’ is disturbing and testifies against the actual authors of the article who understand Brazilian laws as they have worked here many times,” she shares.

The imbroglio involving U. jubatus has identified fossil trafficking as an issue in Brazil. At the same time, it has shown how Brazilian researchers are speaking with the MPF in an effort to repatriate these materials. In the last seven years, the MPF of Juazeiro do Norte introduced at least 10 procedures to investigate the illegal removal of these items from Brazil. “The majority were reported by scientists,” comments Rafael Rayol, federal prosecutor leading the investigations in Brazil. The oldest report references the repatriation of 46 fossils from Araripe, among them the skeleton of a Pterosaur.

Aline M. Ghilardi (UFRN)

The extraction of laminated limestone by mining company workers in Nova Olinda is the key source of new fossil discoveriesAline M. Ghilardi (UFRN)In 2014, biologist Taissa Rodrigues, from the Federal University of Espírito Santo (UFES), learned from an auction site about the sale of a Pterosaur of the species Anhanguera santanae. Geofossiles, a store in Charleville-Mézières, France, that specializes in the sale of fossils, asked for close to R$1 million for the specimen. “It was shocking to see that the skeleton for sale was almost whole, with the head, neck, and wings practically intact,” says Rodrigues. The researcher decided to report the case to the MPF, which sought the help of French authorities.

It did not take long to identify the owner of the specimen: Eldonia, a company specialized in the sale of fossils in Europe. Through a search and seize operation, the French police found the Pterosaur and another 45 fossils of various species, all from Araripe and evaluated at R$2.5 million. The case ended up in the courts. In 2019, the Court of Lyon decided to repatriate the fossils. However, Eldonia appealed and was able to reverse the decision. “We made another claim, and the French authorities again ordered the seizure of the specimens. We are waiting for a final decision to be able to bring them back,” says Rayol.

Biologist Rodrigo Pêgas, who studies Pterosaurs and is doing is PhD at the Federal University of ABC (UFABC), had a similar experience in 2020. “I was looking for Pterosaur images on the internet for a presentation when I found a photo of a Tupandactylus imperator,” he shares. “I clicked on the image and landed on an auction site, which was going to auction off the specimen the following day.” The minimum starting bid: €23,000 (approximately R$147,000). Pêgas clicked on the name of the owner, a German company called Fossil Worldwide, to see what other items were being auctioned. He found various fossils, all from the same northeast region. He reported the site to the MPF, which began to develop a case with German authorities. After identifying the person responsible for the auction, Kaiserslautern federal prosecutors decided on a preemptive seizure of the materials, which would remain in the custody of German authorities until the case went to court.

Different from the United States and some European countries, the fossils in Brazil are considered the property of the State, whether they are found on public or private lands and, therefore, cannot be removed from the country nor sold. The same happens in China, Mongolia, Morocco, and Myanmar (former Burma). The first Brazilian law about fossil patrimony dates back to 1942 and establishes that the extraction of these materials requires the authorization of the DNPM—in 2018, the agency became known as the National Mining Agency (ANM), linked to the Ministry of Mines and Energy. In 1990, the former Ministry of Science and Technology (MCT) published a decree stipulating that foreign scientists also need authorization to carry out collections in Brazil. One year later, the Law of Theft defined as a crime the exploitation of raw material that belongs to the State without authorization. According to Rayol, the document presented by Frey, however, would not justify the removal of U. jubatus. “The decree by MCT is clear that the collection and export of paleontological material requires its authorization.” Martill says he was unaware of the 1990 decree: “I have always worked with the DNPM and I have never been informed of the need to consult another entity.”

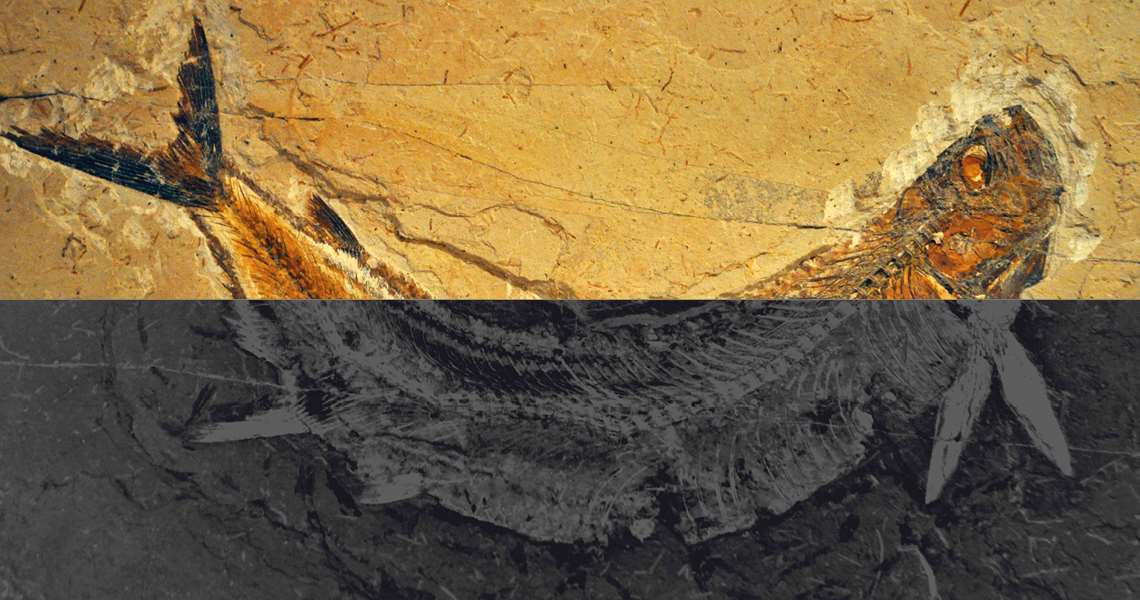

SMYTH, R. et al. Cretaceous Research. 2020

The U. jubatus holotype was found in the Araripe basin, but since 1995 it has been part of the collection of the Karlsruhe Museum in Germany. There is suspicion that the specimen was smuggled out of BrazilSMYTH, R. et al. Cretaceous Research. 2020The MPF was planning to use the document to strengthen the request for repatriation of the holotype. At the same time, the SBP contacted the Karlsruhe museum to discuss the return of the material and prevent the case from reaching the courts, which prolongs the process. “The museum is prepared to negotiate,” says Renato Ghilardi, president of SBP and, despite his last name, is not related to the researcher from UFRN. “In 2016, we were able to reclaim a collection of invertebrates from the Devonian period (between 416 million and 359 million years ago) that were at the museum of the University of Cincinnati in the United States,” he shares. In the case of the Karlsruhe museum, it is assumed that many other Brazilian holotypes are with the collection, many of which were described by Martill and Frey in the 1990s. The news reporters questioned the museum if the repatriation of the U. jubatus would lead to the return of other Brazilian fossils, to which Frey of Germany responded: “This case reached political levels and, for this reason, I cannot offer my opinion. But we are in contact with the authorities.”

Fossil trafficking is a problem in various countries. In Brazil, it tends to be concentrated in the Araripe basin. In part because the region is known to be one of a few that house pre-historic animal fossils with soft tissues that are well preserved. In general, these structures—skin, connective tissues, and internal organs—are the first to decompose and rarely fossilize. In the rare instances they are preserved, this allows for study of the biology and evolution of extinct species from millions of years ago. For these reasons, fossils from Araripe have financial and scientific value. “I have heard from several foreign researchers that fossils from Araripe are very important because they are in Brazil,” comments biologist Antônio Álamo Saraiva, from the Department of Biological Sciences at the Regional University of Cariri (URCA). “I would be thrilled if the museums abroad developed the fossils for Brazil because this way Brazilians would see that it was better that they were smuggled abroad, where they were safe,” confirms Martill of Britain.

Known by Brazilian paleontologists, the researcher has already done several projects in Araripe. He is also a headstrong critic of Brazilian laws that protect fossils, which, in his opinion, obstruct the work of scientists and the development of paleontology. “For many years, the Brazilian government has underfunded its museums. The result? Various fires and the destruction of artifacts of international importance. At least the contingent of fossils in Brazilian museums is very small in relation to those in Germany, the United States, and Japan.”

Brazilian researchers refute the argument. “Since the 1980s, Araripe has had a structured museum that is devoted to the preservation of fossil patrimony in the region,” confirms biologist Allysson Pontes Pinheiro, from the Department of Physical and Biological Sciences at URCA. Located in Santana do Cariri, the Plácido Cidade Nuvens Museum of Paleontology houses a large collection of fossils, which has fostered scientific research and the education of new scientists throughout the country. “In 2005, the government of Ceará took things a step further and created the Araripe Basin National Geopark, in an effort to preserve local fossil deposits.” There are many more institutions across Brazil with the infrastructure and trained workforce to maintain national fossils and study them (see map).