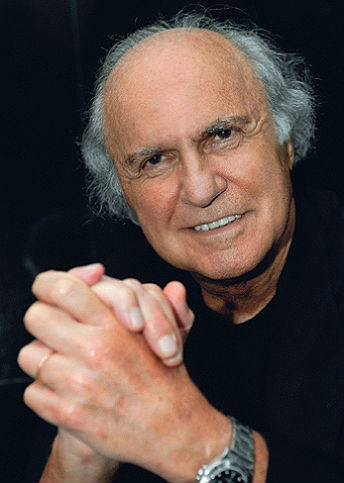

EDUARDO CESARA teacher changed his life. Orchestra conductor Isaac Karabtchevsky was a young 21-year old studying at Mackenzie School. During history classes, he preferred to daydream about music exercises. His teacher noticed that, put his hand on Isaac’s shoulder and said “Karabtchevsky, you don’t belong here.” The student looked at the teacher, said thank you and never came back again. He had decided to study music full time at the Koelreutter Music School. At present, he is the artistic director of the Baccarelli Institute, a social and academic project that provides music education to 1,200 needy children divided into 17 choral groups and four orchestras, including the Heliopolis Symphony Orchestra, housed in the biggest shanty town in São Paulo. The Heliopolis Symphony Orchestra has recently returned from a tour of Europe, where it performed a Beethoven concert in the composer’s native city. Since 2000, Karabtchevsky has also been a professor of conducting at the Conducting Course at Lago del Garda, where he teaches students from all over the world.

EDUARDO CESARA teacher changed his life. Orchestra conductor Isaac Karabtchevsky was a young 21-year old studying at Mackenzie School. During history classes, he preferred to daydream about music exercises. His teacher noticed that, put his hand on Isaac’s shoulder and said “Karabtchevsky, you don’t belong here.” The student looked at the teacher, said thank you and never came back again. He had decided to study music full time at the Koelreutter Music School. At present, he is the artistic director of the Baccarelli Institute, a social and academic project that provides music education to 1,200 needy children divided into 17 choral groups and four orchestras, including the Heliopolis Symphony Orchestra, housed in the biggest shanty town in São Paulo. The Heliopolis Symphony Orchestra has recently returned from a tour of Europe, where it performed a Beethoven concert in the composer’s native city. Since 2000, Karabtchevsky has also been a professor of conducting at the Conducting Course at Lago del Garda, where he teaches students from all over the world.

In his own words, after a stint with the Zionist Movement, “instead of a political party, I founded a choral group in the city of Belo Horizonte in 1955.” It was called Madrigal Renascentista, one of the best-known choral groups ever in Brazil. Isaac, who was passionate about orchestra conducting, got a grant from the German government to study in Freiburg. He returned to Brazil in 1969 to head OSB, the Brazilian Symphony Orchestra, which was slowly dying for lack of an audience. “During the military dictatorship, young people had very little contact with classical music, so it occurred to us to retrieve what had been placed on the sidelines by the regime, namely, access to humanistic studies. This was the starting point of the Youth Concerts and International Concerts series (on the Globo TV network). He also organized Project Aquarius, a series of outdoor concerts that drew thousands of people to Rio de Janeiro’s Quinta da Boa Vista park. Karabtchevsky’s OSB boldly shared a performance with popular singer and composer Chico Buarque on the stage of the Municipal Theatre, creating a huge scandal. Some years later, the conductor organized similar performances with such prominent musicians as Tom Jobim, Cazuza and Caetano Veloso, among others. He spent 26 years as the OSB conductor. “The more traditional conductors insisted on playing only classical music or only popular music, stating that these were totally separate musical genres.” Composer Marlos Nobre even paraphrased a children’s song to ridicule the conductor: “Karabichê tá doente/ Tá com a cabeça quebrada/ Karabichê precisava/ É de uma boa lambada.” [Karabichê is sick, his head is broken, Karabichê deserves a good spanking]. “All I was trying to do was save the OSB from financial disaster, but many people refused to understand this,” he recalls.

After two seasons as artistic director of the São Paulo Municipal Theatre, the conductor moved to Vienna in 1988 as conductor of the Tonkünstler Orchestra. In 1994, he was invited to become the conductor of the orchestra of Venice’s La Fenice theatre, until it burnt down. Today, Karabtchevsky divides his time between Heliopolis, Rio de Janeiro (where he is head conductor of the Petrobras Symphonic Orchestra) and Nantes (where he is the director of the Orchestre National des Pays de la Loire).

When did you decide to become a musician?

I think the decisive factor was having listened to my mother sing when I was growing up. She was an opera singer. Therefore, by listening to her singing, I was directly and indirectly exposed to breathing, with voice modulation, and with this love of melody, this love of singing. I think that’s when I began to glimpse the possibility of dedicating myself to conducting choirs. At the age of 12, I started to think about conducting. I was studying at the Liceu Pasteur school in São Paulo and the music teacher asked me to conduct the choir. And I, without having the faintest idea of how to do this, moved my hands automatically according to the sound. That was a decisive moment.

How did you divide music and politics?

When I joined the Zionist Movement, I wasn’t driven by any political motivation. It was a social movement – the members would get together at my house and I took part in the meetings automatically. I read the major socialist works, I read Marx, Sartre and became acquainted with the Zionist issue and the Jewish issue. This was progressive learning and slowly I acquired political awareness that was more closely related to the formation of the identity of the Jewish people, who were spread all over the world. I didn’t really have any political aspirations. My political involvement, linked to socialism, would come later and once I got more involved, I went through a training program. I took part in a training program in the city of Jundiai, State of São Paulo, where I lived in a farm community – a kibbutz – for one year. This was a preliminary experience – we learned how to farm the land – which is not really a characteristic of the Jewish people. We inverted the values and became aware of the need to create roots in the land itself. But I knew that the experience would not be successful. At that time, I was already beginning to take piano lessons and classes at the Escola Livre de Música conservatory. The commitment to music was in a way a break from the student movement.

So instead of going into politics, you formed a choir.

That’s right. The voice is really the most comprehensive and perfect instrument and the musical instruments of an orchestra are used to try to reproduce the nuances, the details and the coloratura that a voice achieves, without the possibility of confronting or reproducing such a voice. The voice is an absolutely perfect instrument. The voice taught me music, taught me how to be a conductor. I think a conductor has to breathe with the orchestra, he has to sing. The conductor’s technique, his gestures have to transmit the sonority that comes from the voice.

How does a conductor create magic from music?

The conductor doesn’t create anything. In my opinion, there are two psychological references that helped me realize what it means to be a conductor. One is a text by Freud, which evokes the leader, the individual vis-à-vis the masses. Of course, Freud was referring to a very troubled period in Europe; he was thinking of the dictators that stay in power, the individual in relation to the masses. But if you remove the political connotation and the dictator and transform the individual into a conductor and the masses into an orchestra, then the problems are very similar. The maestro is identified with the father figure. This is where Lacan comes in – he is the one who uttered the famous words: Le problème c’est toujours le père [The problem is always the father.] The conductor can also resemble an employer and this leads us to an employer-employee relationship; or the conductor can simply be an individual who is part of the community. I prefer this individual, aligned with the whole and that doesn’t create gaps or barriers that inevitably lead to ruptures. I decided to go into analysis after reading those texts. Because the relationship of the conductor – an individual, an isolated human being – confronted every day by more than 100 musicians inevitably leads to conflict – no matter what kind. If you lack the instruments and mechanisms to conduct a dialogue, if you can’t identify exactly what the points of tension are, then this can lead to inevitable ruptures between conductors and orchestras.

EDUARDO CESARSo the relationship is not really – as people commonly believe – “the only successful dictatorship”?

EDUARDO CESARSo the relationship is not really – as people commonly believe – “the only successful dictatorship”?

I would hesitate to use the word dictatorship in a human relationship whose main element is music. Music doesn’t admit this kind of dictatorship. You conduct a dialogue, you try to reach a relatively unitary conception that is shared by most of the orchestra. Each person has his own way of thinking and the big mystery – and this is in answer to your first question – is how you can persuade, convince everyone, that your version is compatible with what they are thinking. This is where great maestros emerge and the magic that is created is that the maestro is respected and admired by all. Each conductor has an aura around him that must be shared with the group. I’ll give you an example. When I was a conductor in Vienna, I invited the first clarinet of the Berlin Philharmonic to play and we talked about the relation between the musicians and their conductor, Claudio Abbado. He told me: “It’s very complicated, because we are trying to convince him how we play Brahms.” In a group such as that one, it’s possible to talk to Abbado or to Karajan about musical interpretation. I think this is fair, since it comes from a group with such a glorious reputation.

Is it possible to mislead the audience with empty gestures?

If the audience accepts it, then good for it. People mistakenly believe that the prettier the gesture, the better; and if it works with the audience then it’s OK for the orchestra. But this is a lie. Gestures are only authentic when they are impregnated with musical content. Empty gestures made for the audience don’t work. The orchestra realizes this and won’t allow itself to be misled; it knows perfectly well that there are gestures directed at the musicians and gestures directed at the audience. No matter how beautiful and perfect the maestro’s gesture is, if it doesn’t correspond to a musical truth, the audience will become bored. It might even become enthusiastic about the gesture itself, but this turns into an empty relationship that leads to nothing and the orchestra doesn’t reciprocate. When an orchestra plays without emotion, the audience feels it.

How do gestures work in conducting?

Gestures are the neuralgic point of our activity: “How can one establish a set of gestures compatible with the musical content?” Over the years, you turn more and more inwards. As the years go by, my gestures have become more contained and I focus on what is absolutely fundamental. I think this is what all conductors wish to achieve. And as you get older, this issue becomes more apparent. Because clearly you don’t have the same energy as you had when you were 20 or 25, so you contain your gestures to their fair proportion and from then onwards music becomes the result of a non-demagogical process, a process of awareness. If you watch the old films of Karajan conducting, you’ll see how he becomes increasingly contained and able to express the maximum with the minimum, just with his eyes. There is a recording of composer Richard Strauss, conducting his opera Der Rosenkavalier shortly before he died. It is really impressive – when you look at how concentrated the musicians were, their fascination with the conductor and Strauss’ influence on them; there were no gestures; there was practically an immobility where gestures were concerned. Strauss gave you goose bumps, it was so moving; he was able to lead the musicians to cohesion through a minimum of gestures. This is the dream of all good maestros. Every conductor has his own garbage dump and this is where he throws away all the gestures he no longer uses. Sometimes you go back to the garbage dump to pick up some gestures that are effective at a given moment. You use them and then you throw them back onto the garbage dump.

Is it possible to conduct a work for years and still find new things to reveal about it?

Listen to various cycles of Beethoven’s symphonies conducted by Karajan and you will see how he was able to create two totally different worlds in each phase of his life. In other words, there are no rules that impose a specific interpretation criterion that cannot be changed; sometimes the criteria undergo profound changes. The example of Beethoven’s symphonies and Karajan is that, according to the maestro’s life stages, the symphonies were submitted to different views, to various ways of thinking; sometimes it was a tiny detail that enhanced the entire work. It is the sum of those details that makes conducting during one phase different from conducting during another phase, when he hadn’t observed these details. In my case, I always study. Even works that I have conducted countless times; I never stop studying. My music scores always have notes and I write down the year on which I wrote a given note so that later, when I re-evaluate those music scores, I can think to myself “that’s how I used to think 15 years ago; now I think differently.” This is the fascination that a music score exerts over the musician. The musician is subject to a constant process of renovation and this is good. Music is completely different from speech. You can play a music phrase in hundreds of different ways and the pace that you give to this music phrase can also be special. If you say something very quickly to someone, you run the risk of being misunderstood. But you can do this with music. You can create paces according to the way you feel the music, even if you aren?t following all of the composer’s recommendations.

Nowadays, there are many great conductors and very few great composers. Are we living in an era where reproduction is more powerful than creation?

Yes, undoubtedly. I think we really live through waves: this is how the world is; there are times when the weather is hotter, it’s confusing, nobody is able to understand the weather – too much snow in Europe, excessive heat and floods in Latin America. I think this cultural world is driven by these invisible forces that suddenly come up with a constellation of geniuses, which is what happened in Vienna at a given period, in which Beethoven, Mozart, Haydn, and Schubert lived almost simultaneously and, a little later, Schumann, Brahms, and then Wagner. In short, Vienna was a capital city that could be proud of the fact that it concentrated the most spectacular constellation of creative composers in a given period. And this has never happened again. Why? Nobody knows. It’s those famous waves. All of a sudden, they produce a series of amazing composers. We are not even close to the level of creativity that appeared in Vienna in the early nineteenth century.

Few conductors are also composers. Why is someone so closely linked to music unable to compose?

Composing music is a talent. It is an irrepressible talent that leads someone to compose. Unfortunately, I don’t have this talent, but I admire those who have this ability to express themselves. I think composing is so absorbing that I would not be able to be involved in both activities at the same time. I admire a composer like Mahler, for example, who was basically a conductor and would compose his music while spending the months of June and July in a little house down by a lake. That was where he composed his masterpieces. I don’t understand this – these are geniuses. I don’t understand geniuses.

EDUARDO CESARYou are fascinated by Mahler, a composer who was obsessed with death.

EDUARDO CESARYou are fascinated by Mahler, a composer who was obsessed with death.

I think so. Nobody escapes death. No sensitive, deep-thinking human being escapes confronting finiteness. When you are in the position of the interpreter, it is impossible to prevent these feelings from being conveyed in your way of saying things. And everything changes. Everything simply changes. That view that you had before transforms itself with the death of the human being. I discuss with my analyst if this obsession is something sensible and he answers me in the manner of Lacan: “No, you are seeking the invisible, because death is invisible. Go, penetrate death, dive into death.” What does he mean by this? Dive into death, dive into music.

A concert is something ephemeral, something that doesn’t repeat itself. How do you describe this feeling?

I think the moment is important; you shouldn’t worry about transcendence. The worthwhile moments are the minutes during which you achieve the sublime. They reinvigorate you, they restore you, they drive you to search for other moments like this one. When a concert reaches its peak, I am not aware of what goes is going on. This peak is achieved when I conduct a good concert. There is fullness only when you achieve beauty. When you are aware that the concert wasn’t good, you feel defeated.

When is it necessary to respect the composer and when is it better to betray the composer?

It’s always good to respect the composer. But now, for example, I am beginning to record, together with Osesp, the São Paulo State Symphony Orchestra, Villa-Lobos’ 11 symphonies. I have studied them and I´m going to conduct them for the first time. And I think this is the first time that a Brazilian orchestra has had the challenge of recording them. The musical scores are being submitted to in-depth studies by Osesp. The musical scores were reformulated based on the manuscripts. But when you think of a symphony, the first thing that comes to a musician’s mind is the sonata form with the two themes, the movements, the cadence, exposition, coda, etc., those principles that were created in the eighteenth century and that have been in effect ever since then. Villa-Lobos, for example, didn’t pay much attention to the sonata form. He was more inclined toward rhapsodies. And this is why it is important, for us Brazilians, for a Brazilian orchestra, to record his music. We are aware of and familiar with the musical language of Villa-Lobos. He was rhapsody-like and the rhapsody elements are always present, even if only in the first theme, etc. But one needs to improvise, just like a musician improvises a chorinho, or a guitar prelude. One must improvise. The biggest challenge of Villa Lobos’ symphonies is to find the moment when you can grant yourself this freedom. This is a good example in which “betraying” the composer’s work can provide an even better interpretation than the one he originally envisaged.

Is there still prejudice against combining popular and classical music?

This debate is totally outdated. At that time, the battle was against this kind of prejudice; it was all that elitism – a false elitism, because there are reciprocal elements in popular music and classical music and they complement each other. They are offshoots from the same source, that is, from music, which is a universal source. The offshoots are classical music on one hand, popular music on the other hand, country music…But they all integrate in a certain way. I think that each experience, each musical contact is valid, provided that it leads to a curiosity, to a restlessness. When I was at the OSB, my challenge was to fill the cultural void with a movement that would meet the needs of young people wishing to have contact with music. There is only one kind of sensitivity. If a youth is sensitive to popular music, he will certainly be sensitive to classical music. It is only necessary to divulge music and give youth the opportunity to be allowed to become familiar with this music. Sensitivity cannot be curtailed; it is a global and unitary phenomenon. At the time, it was a mystery because the two musical genres were separate. But Brazilians are highly musical and sensitive to any kind of music. I don’t see any barrier between good popular music and good classical music and I always believed there is a communication link between the two, a deep, historical link, as the two musical genres influenced each other in the course of history. During the nine years during which I was the conductor of Venice’s La Fenice, I wanted to perform Verdi’s Aida. Then the theater caught fire, precisely in 1996, when I was the head conductor. The theater was virtually destroyed by the fire. My wife and I were in Warsaw at that time, and I saw everything on television. But as musical production never stops, when we went back to Venice we saw that the mayor had ordered that a tent be put up – it was a huge circus tent with air conditioning, central heating, dressing rooms equipped with telephones – everything was there. You could swear you were in a theater. We performed in that circus tent for the entire season – including all of Mahler’s symphonies. And in spite of everything, that was a rich period during which opera was performed one evening and a symphonic concert the next. That was the most productive period of my life. I recall that I was conducting Verdi’s Rigoletto, which has a famous tempest scene and at that very moment, a huge rainstorm fell on that circus tent. The director said to me: “That was the most realistic opera I have ever seen in my life.” The storm was not virtual; it was visible, it complemented the scene – it was absolutely fantastic and enhanced the power of music.

Based on your experiences – such as this one – how do you view the experience of conducting an orchestra whose members are young people who live in the Heliopolis slum?

I was fascinated with what I saw. I didn’t need to go prospecting for talents – I had them right in front of me. Here you don’t have to prospect for talents like you do for oil. The real Brazilian talents are on the surface, in unexpected places. What I saw in Heliopolis was fascinating – those boys practicing Mahler’s second symphony. Those youngsters come from a world that is totally unrelated to the Brazilian elite. How do they manage to feel the music and struggle to create something with so much quality? This allows you to conclude that music is such an absorbing phenomenon that it invades the human body from a very early age. Music invades us, regardless of the condition, the social class, of whether you have an intellect or not; it invades you, flows out of our nerve endings; it establishes a beginning and arouses interest in the communication of art. I think the most important thing is for a person to start with music rather than to start with another form of art, which demands intellectual competency. Music is so strong that it is conditioned to our heartbeat. It is born with the heartbeat. And this heartbeat is something permanent. These kids come from precarious social conditions and through music they are acquiring an identity, an awareness of themselves. From the moment they hold a violin in their hands, sit down in front of the music stand and play, they have a name and a surname and a social position. This is what is happening in Heliopolis. I don’t know what would become of them if it weren’t for the music. Before, there was a false vision of people who don’t believe in the human being. “Oh, those people from the hillside slum, let’s give them a fiddle, a tambourine, because they know how to play the tambourine.” Give them a violin. And give them a music school that has professors from Osesp and from the Municipal Theatre to work with them. Give them an oboe, a flute. You will cry – there is no other possible reaction except crying. Traditional orchestras whose members are young musicians normally do not show any emotions. Their attitude, their reaction to musical culture is a most serious relationship – no smiles on their faces. Orchestras such as the Heliopolis orchestra establish another kind of communication, a more playful one, with the audience. I think that this is fantastic, a moment of renovation which undoubtedly comes from Latin America and I’m very proud that it comes from Latin America.

What does professor Karabtchevsky tell his students?

The first thing I tell them is: “It’s difficult. The greatest qualities of a conductor are persistence, perseverance and obstinacy. The conductor must trust his talent and must deal with this daily confrontation with an orchestra.” This confrontation with the orchestra is what enables you to achieve sonority. You practice a specific gesture and expect this gesture to result in a musical correspondence. If a young conductor makes a gesture, nothing happens.

What is it like to have the orchestra as your instrument?

It is the power of the gesture. The gesture is an instrument. You can do this in relation to the piano as well. All you have to do is touch a key and you produce a sound. A fixed sound. That is more or less what an orchestra is all about; you press a key. But this is not the essential element.

What is the essential element?

The essential element is what is hiding behind the gesture. The essential element for any musician and conductor is what underlies the musical notes, waiting to be unveiled.