Born in Lima, climatologist José Antonio Marengo got his degree in physics and meteorology in Peru and spent eight years in the United States, where he completed his PhD and two postdoctoral fellowships, before putting down roots in the Paraíba Valley in the state of São Paulo more than two decades ago. He worked for 15 years at the Center for Weather Forecasting and Climate Studies (CPTEC) of the National Institute for Space Research (INPE) in the city of Cachoeira Paulista, where he became the scientific coordinator for climate forecasting. In 2011, he became general coordinator of the Center for Earth System Science (CCST), also linked to INPE. A specialist in climate modeling and climate change, Marengo has contributed to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) since the mid-1990s, when it released the second of its five famous reports.

His great familiarity with these subjects led him to be chosen to head the research and development sector of the National Center for Natural Disaster Monitoring and Alerts (CEMADEN) in 2014, an agency of the Brazilian Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovation, and Communications (MCTIC) based in São José dos Campos. Among other activities, CEMADEN monitors risk areas around the clock in 957 Brazilian municipalities classified as vulnerable to natural disasters. In parallel to the center’s activities, Marengo teaches meteorology and earth system science in INPE’s postgraduate programs, participates in national and international research groups, and produces scientific papers and reports.

In this interview, the climatologist, whose humorous conversation is punctuated by his Spanish vocabulary and accent, details his view of how populations and governments perceive climate change and its possible consequences.

Specialty

Climate modeling and climate change

Education

Undergraduate degree in physics and meteorology at the National Agrarian University, Lima, Peru (1981), and a PhD in meteorology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA (1991)

Institution

National Center for Natural Disaster Monitoring and Alerts (CEMADEN)

Scientific production

188 scientific articles

Why did you come to work in Brazil?

I was educated at the National Agrarian University of Lima, which has a five-year bachelor’s degree program in meteorology and physics. I chose this area because my father was a meteorological technician and worked for the Ministry of Agriculture. In Peru, after five years in the bachelor’s degree program, you have to write a thesis to become a meteorological engineer. I did my thesis on the Amazon. That was how my interest in the region began. The choice of thesis topic happens during your last year of school. At that time, in the early 1980s, I came across a work by Eneas Salati, a professor at the Center for Nuclear Energy in Agriculture at the University of São Paulo in Piracaba, on recycling in the Amazon, which had been published in the late 1970s. This caught my attention because Peru is also an Amazonian country. I did a master’s degree in water resources at the same university, where I was a teacher for almost seven years.

Then you went to the United States to do a doctorate.

I received a scholarship from the National Science Foundation, in the United States, and went to the University of Wisconsin-Madison. I spent four years there and wrote my thesis on the Amazon and climate modeling. Then I did a two-year postdoctoral fellowship at Columbia University and NASA’s Goddard Institute in New York, where I worked even more with climate modeling. Then I did another two-year postdoctoral fellowship at Florida State University, on tropical weather. My focus during this period was the climate of the Sahel, the semiarid belt across Africa between the Sahara desert to the north and the savannah to the south. After eight years in the United States, I wanted to return to South America. But at that time, the mid-1990s, Peru was in the midst of the terrorism crisis. Argentina wasn’t a good option for me because I wouldn’t be developing my area of research in climate modeling. Carlos Nobre [an INPE climatologist] invited me to come to Brazil as a fellow of the CNPq [National Council for Scientific and Technological Development]. I was single; I came and I ended up staying. I got married and I have a Brazilian son. I’ll never leave here.

Did you have a specific connection to Brazil?

I didn’t, but Carlos did. I studied in Wisconsin from 1987 to 1991. In 1988, my advisor invited Carlos to give a lecture there. I knew his articles and he knew mine. He asked me where I was going when I finished my doctorate and encouraged me to come to Brazil, but I didn’t know exactly what I was going to do. I was thinking of staying in the United States, but I knew that it would be difficult to arrange a stable position at a university there. Later, when I’d finished my postdoc, I talked to Carlos again and asked him if he remembered our conversation. He invited me to come to Brazil. I came to work at CPTEC, where I spent many years.

What were you doing at CPTEC?

We began developing the climate studies area, to do more research on El Niño [the warming of the Pacific Ocean waters that causes changes in weather], and to work on models for seasonal climate forecasting. Over time, the federal government got energized about these issues and realized more discussion is needed regarding the impacts of global changes. In addition, the IPCC received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007 and this generated a lot of interest in the subject of climate change and its impacts on Brazil. I was part of the team of authors from Brazil who prepared the 2007 IPCC report. Then INPE created the Center for Earth System Science in 2008. I headed the center from 2011 to 2014 and we began working, among other subjects, on the issue of population vulnerability to extreme events and the possibilities of adapting to these changes. I really like this subject. At that time, several studies on natural disasters began to emerge. Then, following the tragedy in the mountains of Rio de Janeiro in January 2011 [rains followed by landslides that killed more than 900 people], the federal government quickly created CEMADEN. We had supercomputers in this country and something had to be done to try to avoid such disasters. Since I had worked a lot with extreme weather events, I could help in monitoring and managing the risks of natural disasters.

Is it correct to say that natural disasters are always associated with extreme weather events?

An extreme meteorological event, like an intense rain, is not a disaster. In this case, the disaster is the impacts caused by rain on a population that’s vulnerable to this extreme phenomenon. There is no population in the middle of the Amazon. A strong rain can fall there and it won’t produce a disaster of any sort, because there aren’t any people living there, or there are very few. In Brazil, high impact disasters such as floods, torrents, landslides, or droughts occur in the Southeast, South, and Northeast regions, where there are the largest concentrations of people. We need to develop further studies on the disaster risks of possible future climate scenarios. Will vulnerability to this type of event be the same in a few decades or is the situation going to worsen or improve? We have to work on adaptation scenarios for climate change, and risk reduction. This is our agenda at MCTIC and the Ministry of the Environment.

Heavy rainfall is not a natural disaster, but the impacts it causes on a vulnerable population are

Is Brazilian society convinced that climate change is happening, and of its risks?

Nature is sending signals here and around the world. The climatic extremes are getting worse. It’s enough to recall the great drought in the Northeast that began six or seven years ago, and the droughts and floods in the Amazon. People realize that the climate is changing, they even make jokes about it. We always try to explain that climate change is a natural process, but that it’s being accelerated by human activity. It’s not man who changes the climate. But with increasing greenhouse gases and deforestation, man’s role in this process is growing increasingly larger. That’s what people still don’t understand. Perhaps they don’t understand the theoretical basis behind the changes, the attribution of causes of these changes that we scientists have adopted. The main message, that the climate is changing, is understood now. It’s not necessary to wait until 2050 for this to be clear. Winters and summers are more intense. Elderly people may die as a result of heat waves. This is already happening in Europe where the population is more adapted to colder weather.

What are Brazil’s biggest vulnerabilities?

These factors have begun to be evaluated only recently. For some time, Brazil fought for the cause of mitigating the changes, for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, believing that these measures would generate carbon credit mechanisms that would bring more money in for research. That didn’t happen. Vulnerabilities in Brazil differ in each region. The Northeast has recurrent droughts but the population hasn’t yet adapted to these conditions. Israel has the same climate as the Northeast, but is adapted to go through periods without rain and has advanced irrigation technology that allows it to adapt to drought conditions. Vulnerability has a physical basis, but there’s also a social basis: people may—or may not—be adapted and live in exposed areas that are highly vulnerable to landslides or to urban or rural flooding. That is, they may or may not be vulnerable to natural disasters. For example, in the metropolitan area of São Paulo—an economic powerhouse with its 20 million inhabitants—there was a lack of water between 2014 and 2016, and rationing was started. In this case, the climate models indicated that this drought in São Paulo was a natural phenomenon, but one that could be repeated in the future.

Isn’t it possible to attribute the São Paulo water crisis, at least partially, to human activity?

Causal attribution studies for extreme weather events are beginning to appear now. They are very complicated in terms of statistics and modeling. In the Southeast, we had 47 days without rain between January and February 2014. Usually this sequence of dry days lasts between 11 and 15 days. This is a meteorological phenomenon we call atmospheric blocking. A hot air bubble forms and the moisture that usually comes from the Amazon cannot enter the region. It circulates back to Acre or Rondônia. In January 2014, there were record rains there and a record drought in São Paulo. Moreover, on that occasion, the cold fronts which bring rain from the South also failed to reach the Southeast and stayed down there. There are studies that are attempting to determine if this meteorological phenomenon was a consequence of human activity or not. So far there is nothing conclusive. But it can be stated that the water crisis in the metropolitan area of São Paulo, particularly in 2014, was due to the drought, and aggravated by increases in population and water consumption during an excessively hot summer.

Can climate modeling separate what’s natural and what’s human influenced?

With a model it’s possible to do anything. Some include only the natural variability of the climate, while others also include anthropogenic variability or a combination of the two. If we run a model with only natural variability and realize that it doesn’t explain what is being observed in nature, we start in with the other approach. We use a model in which we include the effects that we attribute to the increase of greenhouse gases and compare it to see if the result is similar to what is actually observed. If this model is able to explain the conditions, we begin to adopt the view that human activity has some effect on the climatic event being analyzed. Of course we do a statistical treatment to see if this human influence is significant. In the specific case of the drought in the Southeast, I haven’t yet seen a paper stating whether it was natural or anthropogenic. Nothing shows that the 47 days without rain generated by atmospheric blocking had an anthropic cause. Perhaps the water crisis itself had anthropogenic causes, but not the lack of rainfall.

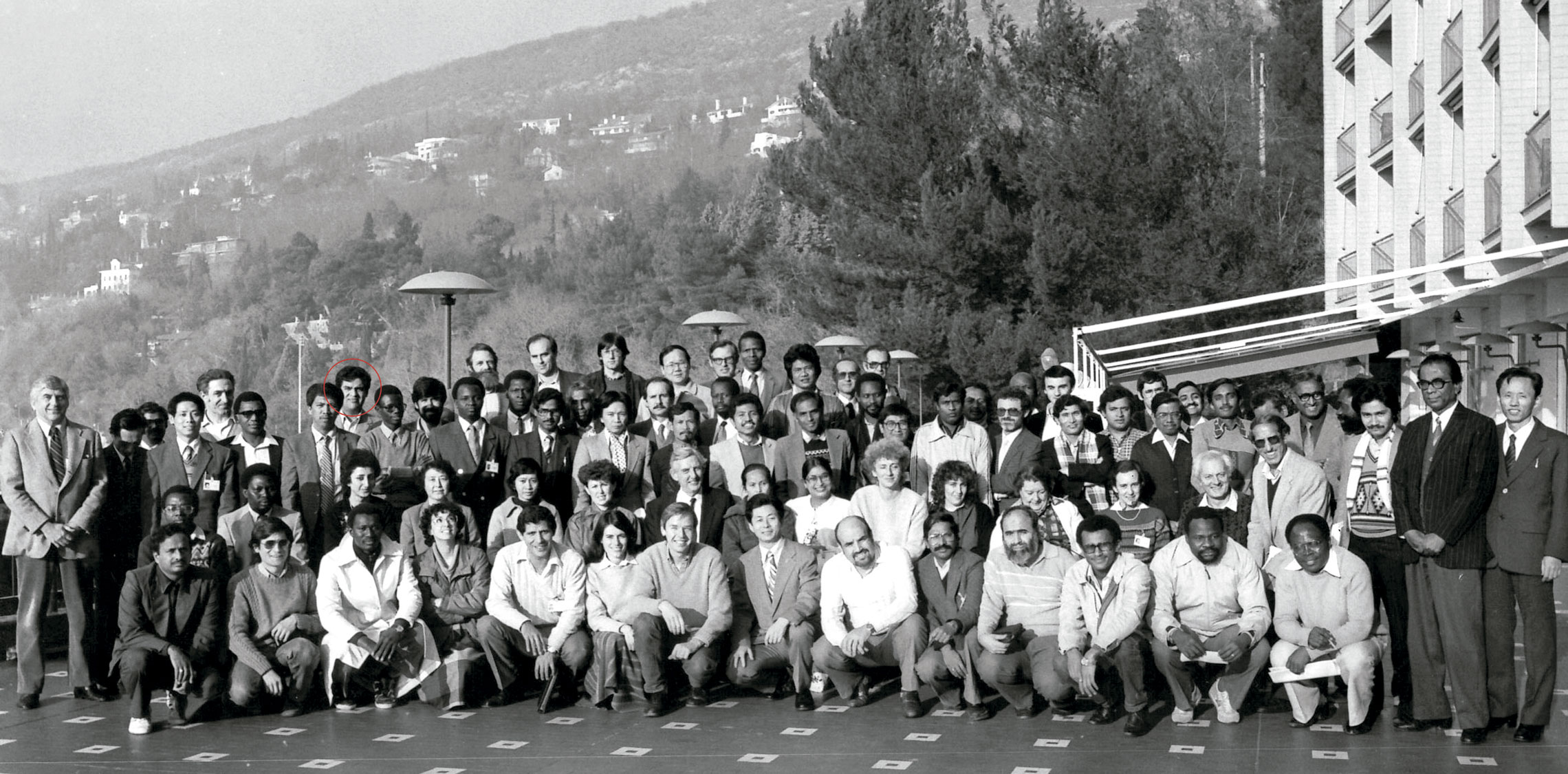

The climatologist (circled) at a theoretical physics course in Trieste, Italy, in 1985Personal archive

In what sense?

The average temperature during the summer of 2014 was almost two degrees higher than normal. The reservoirs emptied quickly—and the population of São Paulo never stops growing. Under these conditions, even if it had rained a little it wouldn’t have been sufficient to end the water crisis. Some research centers in the United States and the United Kingdom say that the intense heat waves and extreme summers in Europe, which have been recurring over recent years, have a clear human cause linked to global warming. It is very difficult to attribute a particular event to a long-term trend. Throughout the world, climate attribution studies are appearing, which is a new line of research. They’re important because they could convince decision makers that what is occurring has a significant contribution from human activities. As I said, the process is natural, but human activities aggravate it.

What is the degree of reliability of climate models? To what extent is it possible to extrapolate the future climate?

We use models developed by climate centers around the world, including Brazil, which contribute to the IPCC reports. A model is a mathematical representation of reality. The entire process is represented by systems of equations that are solved with the help of a supercomputer. But the different modeling centers—from Europe, Asia, Latin America, Australia, South Africa, and the United States—each have their own model developed by their researchers. All of these models are used to project the future climate up to 2050 and 2100. Regarding some areas, and for some climate variables, the models converge. All the models indicate a reduction in rainfall in the eastern Amazon and the Northeast and increased rainfall for southern Brazil and northern Argentina, and the northern coast of Peru and Ecuador. The trend in the models is the same, only the values obtained differ a bit. In areas such as the Central West and Southeast some models show more rains and others less. In these cases, uncertainties arise. If I’m asked if it’s going to rain more or less in Brasília in the coming decades, I have to answer that it depends on the model that’s adopted. Some show an increase in rainfall, others a decrease. On the issue of temperature all the models indicate global and regional warming. All of them. There is consensus. We have a greater degree of certainty about temperature than about rainfall. That’s why global warming is spoken of so much.

You mentioned the eastern Amazon. What do the models indicate about the future climate in the western Amazonian region?

In the models used in the fifth IPCC report, extreme rainfall was projected to increase in western Amazonia. The representation of the forest is better in current models than in the past models. This leads us to think that perhaps the models are improving, that they may be closer to reality. It’s necessary to be careful when projecting the future climate, because there are uncertainties that we can’t eliminate. We must remember that there is no model in the world that can represent reality 100%. There is no perfect model.

Is it a mistake to see the Amazon as a unique region from the point of view of the climate?

We can talk about three different situations. We have the region’s eastern part, which is near the mouth of the Amazon river; the west, near Colombia and Peru, which is rainier; and the southern Amazon, where Mato Grosso and the so-called arch of deforestation is. There is less consensus among climate models regarding the southern Amazon. There are studies saying that deforestation in this region will produce less rainfall and others saying it will produce more. Why would there be more rain? When an area is deforested, there are sectors without forest alongside others where the forest is preserved. The contrast creates a kind of breeze that could produce rain along those borders. This is a regional detail that the large-scale models don’t capture. That is why we also use regional models, which give more detail.

What is the resolution of INPE’s regional model?

The regional model can predict the climate for an area equivalent to a square 40 by 40 kilometers, for all of South America and Central America. But for some areas of Brazil, such as the Southeast, the resolution can get down to a square of 5 by 5 kilometers. We did a study with this level of detail in Santos, on the coast of São Paulo. We found that the port may not be affected by climate change in the future, but the city will be hit by more high surf events, which are the result of more winds being generated by storms near the coast. Our studies have indicated an intensification of storms at that location. We aren’t saying that the sea level will swallow the city, as is shown in environmental disaster movies. A small increase in sea level causes waves to enter further into the city. We’re already seeing news images of water from storm surges reaching the city sidewalks and flooding the underground parking lots of the buildings in Santos. It’s a situation that has serious impacts, even more so if it becomes the norm in the future. For this reason, the authorities in Santos are paying attention to the studies.

Are the studies on Santos the most detailed regarding the possible impacts on a place in Brazil?

I would say so, yes. We have been able to do projections for the city both with and without the adoption of measures for adapting to changes in the climate. We define these measures together with the local population. Managing ecosystems, such as revitalizing the city’s mangrove swamp, is much cheaper than investing in infrastructure, such as building a concrete dike along the beach. The mangrove acts like a filter, or a sponge, and reduces the risk of flooding due to rising sea levels. In Ponta da Praia, one of the city’s districts, the mitigation option discussed was to build a dike, but the residents didn’t like having a wall on the beach. They said it would be ugly. However, studies indicate that either a dyke is built there or they live with the floods.

Is it still possible to prevent the planet’s average temperature rising at least 2 degrees by the end of the century?

If, right now, all the world’s countries were to zero their carbon dioxide—CO2—emissions, the world would still continue to heat up, since there’s already a lot of this gas stored in the atmosphere. In a utopian world, forests and oceans could handle absorbing this CO2 and clean up the atmosphere. But this, unfortunately, is not happening. Studies indicate that in some areas the ocean is saturated with CO2 and can’t absorb more gas. In addition, we know that forested areas are in decline. People cut down trees that are 50 or 100 years old and say they’ll compensate for it with reforestation. The effect of this compensation is small. The trees will be slow to grow. The ideal option would be ending deforestation and increasing the forested area. If there are intense mitigation measures, it may be possible to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees or a maximum of 2 degrees. With uncontrolled warming, if the global temperature rises more than 4 degrees, we’ll enter what we call dangerous climate changes. In that case, adapting will no longer be possible.

In some parts of the world?

I would say in general. People say that if it gets really hot, they’ll turn on the air conditioning. It happens that air conditioners need electrical energy, which depends on hydropower, which depends on rain. But if it gets too hot, the water evaporates and won’t turn the turbines. People still don’t understand the issue of adaptation. Using a water truck in the Northeast only during a dry spell is not adaptation. It’s palliative. Adaptation is something that’s prepared and permanent. In that sense, what could help the world is a large-scale increase in forested area, which absorbs greenhouse gases. There are those who envision that injecting CO2 into holes in the ground would be a mitigation alternative for combatting global warming. This could solve the atmospheric problem and create one that’s geological. There is serious research in this area, called geoengineering, but there aren’t any concrete results from studies showing that such intervention works. It’s a new area. In the 1970s, when climate modeling began, no one believed in it either. Today everyone uses modeling. Maybe this will happen in the future with geoengineering, but it’s still too early to bet on it.

For the climate, there’s no difference whatsoever whether a tree has been cut down legally or illegally.

Is any part of Brazil adapted to extreme events?

To some extent, it appears that the greater metropolitan area of São Paulo has adapted to the water crisis. Authorities say they have improved the water distribution network, which was quite old, and have also begun to collect water from the Paraíba do Sul River. This measure could be considered a type of adaptation. But which districts can adapt to extreme weather events? When it rains a lot in the city of São Paulo people can’t get around. Cars are lost, trucks can’t transport food to supermarkets, buses stop running, people can’t get to work. This happens every summer. I’ve been in Brazil for 20 years and I’ve seen it every year. The city has not adapted to intense rains, which are increasing. In the worst case, when adaptation isn’t possible, people can try to migrate, as is still happening in the Northeast.

What good examples of adaptation to climate change stand out in the world?

Venice is one of them, with the city having lived for so long with the lagoon. Perhaps the best example would be the Netherlands. The city of Amsterdam is below sea level. Without the dikes to hold back the water, the population dies. The country grew as it advanced on the sea. Today, this process would be described as an adaptation. There are projections indicating that more intense storms coming from the North Sea could reach the Netherlands. What if they breach the dikes? In the United States, there was the case of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Its winds pushed the Mississippi River over the walls of the levees that protected New Orleans. They resisted category three hurricanes, but Katrina came in at category five. The city was flooded and 1,500 people died. This happened in a country in the so-called First World.

Will poor countries be the most affected by climate change?

Changes in climate are democratic. They affect rich and poor. The environmental agenda is marvelous. But with the recent economic crisis in Europe and the United States, it’s been pushed to the back burner. The carbon-based economy generates a lot of jobs and governments prefer to fight the crisis by encouraging activities that are polluting. That’s why the United States hasn’t ratified the Kyoto protocol, and left the Paris climate deal. In Brazil, it’s not very different, although the country continues as a signatory of the international climate agreements. Brazil has committed to ending illegal deforestation. But to me, the right thing would be to simply end deforestation, any deforestation, legal or illegal. For the climate, there’s no difference whatsoever whether a tree has been cut down legally or illegally. If it’s been cut down, it ceases to be an agent acting against the increase of the greenhouse effect.