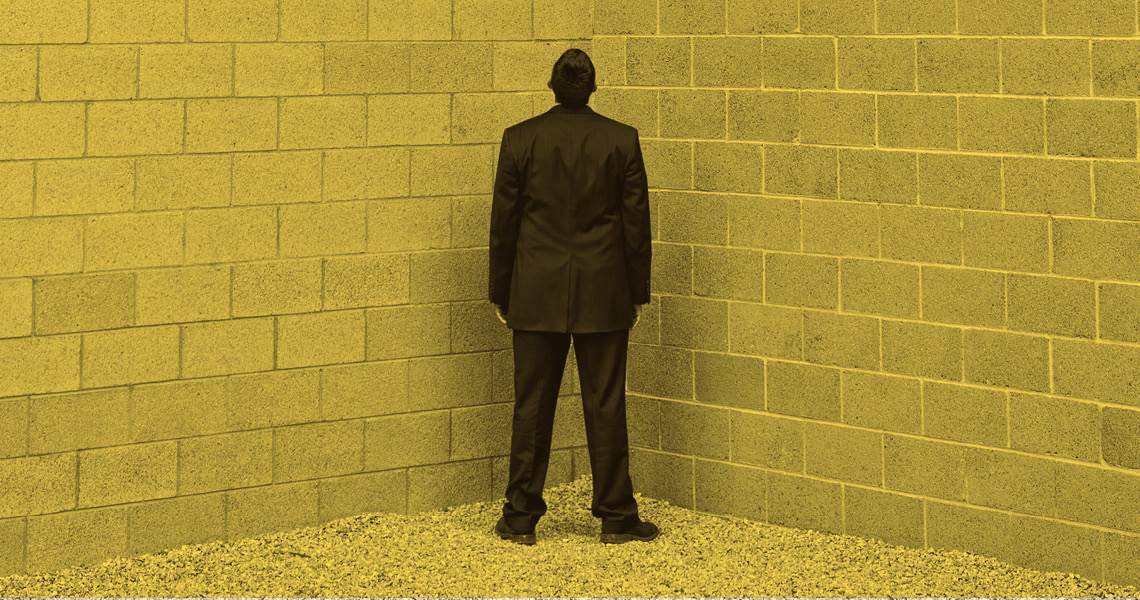

San Francisco–based medical science journal Cureus recently adopted an unusual punishment for researchers whose articles were retracted for scientific misconduct. It launched a “Wall of Shame” on its website that includes the names, affiliations, and photographs of authors of papers the journal has had to retract for plagiarism, peer-review fraud, data falsification, and image manipulation.

The list currently features 11 names, seven of which are from Pakistan, with the rest from South Africa, Nepal, India, and the USA. There is also a reference to Lady Willingdon Hospital at King Edward Medical University in Lahore, Pakistan, for its links to several authors accused of plagiarism. The most serious case is Pakistani epidemiologist Rahil Barkat, from Indus Hospital in Karachi, who had 15 articles retracted by Cureus, including three on COVID-19, for data theft, false declarations of trial approvals by ethics committees, and for charging US$300 fees to list coauthors who did not contribute to the studies. Another example is Ahmed Elkhouly, a resident physician at the St. Francis Medical Center in Trenton New Jersey, USA, who has had five articles retracted. He bypassed the peer-review process by appointing his own wife to review his papers, without declaring the conflict of interest.

The “Wall of Shame” has caused controversy in the scientific community. In an online poll conducted by the website Retraction Watch, 59% of 429 respondents said the initiative was a bad idea. The criticism is partly related to the criteria adopted by the Cureus to select which scientists should be named and shamed. Only the corresponding authors of the articles are exposed, sparing any coauthors from the public humiliation. “Finger-pointing exercises add nothing to the scholarly process, and can be highly detrimental to individuals. Editors have better tools to fight fraud,” wrote Sylvain Bernès Flouriot, from the Institute of Physics at the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla in Mexico, who gave his opinion on the poll.

David Sanders, an academic integrity expert from Purdue University in Indiana, USA, told the Times Higher Education (THE) that the emphasis Cureus places on individual behavior is wrong. “A list of all articles with evidence of misconduct, including the names of all authors and their affiliations, would be more appropriate, in my opinion,” he said. “If the journal really wants to promote scientific integrity, it should improve its peer-review protocols.”

Others applauded the initiative. “This is something every journal should follow to reduce plagiarism and other unethical practices and encourage the submission of genuine articles,” tweeted Dr. Pentapati Siva Santosh Kumar, from the Center for Community Medicine in New Delhi, India. Cureus Editor in Chief John Adler, a neurosurgeon and professor at Stanford University, admitted that the strategy could impact the authors’ careers. “In some cases, this could even be a positive thing. It may be unfair in many circumstances, but not in all,” he told THE.

Cureus’s vulnerability to unethical authors is explained by its peer-review model. Manuscripts are reviewed by experts in a short time period to speed up the process, and critical analysis of the content continues after publication. Anyone is able to give an opinion on published papers, but comments made by experts in the article’s field hold more weight. According to Adler, the list was created after half a decade of discussion by the journal’s editorial board. “The goal was never gratuitous humiliation or punishment—we want to reduce the amount of dishonest behavior our team faces on a daily basis.” He highlights that false scientific information about health can have real consequences on people’s lives, which in his opinion, justifies the harsh approach.

Identifying errors in scientific articles and retracting them, whether the result of misconduct or an honest mistake, is an essential part of science’s self-correction system. In an ideal world, researchers who publish papers containing data errors or wrongful conclusions would be the first to admit their mistakes and correct them. But this is not always the case. Having an article retracted can cast a shadow on a student’s or scientist’s résumé. There have been extreme cases where the humiliation caused by a retraction resulted in tragedy. Sylvain Bernès Flouriot recalled the “sad example” of Japanese biologist Yoshiki Sasai, from the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology in Kobe, who took his own life in 2014, aged 52, after being accused of negligence in supervising his PhD student Haruko Obokata. The student was involved in a scandal in Japan after she fabricated data in two articles about a stem-cell production technique, with Sasai named as a coauthor. Both were retracted by the journal Nature.

One of the problems with Cureus’s approach to exposing researchers is that even if it only does so for cases of major misconduct, it can still increase the stigma of having a paper retracted. Marianne Evola, director of the Office of Responsible Research at Texas Tech University, USA, highlighted this downside in a text published on the institution’s website in 2016. According to Evola, the more that retraction is seen as a means of punishment, the more reluctant scientists are to admit to mistakes, which is detrimental to scientific integrity. She offered suggestions on how advisors and students should deal with this problem. “Students have to be willing to confess their failures to their mentor and be confident that their mentor will work with them to correct the problems. If students or subordinates feel that their failures will be met with shame, humiliation, and punishment, they would be more likely to hide their failure. After years of mentoring students, I learned that seldom was there a need to shame or humiliate a student for their failures, even the avoidable errors,” she said. In an editorial published in December 2021, the journal Nature Human Behavior recommended rewarding early-career scientists who own up when they make mistakes in good faith. “Retractions are a tool for correcting the literature—not a verdict on moral character,” the editorial summarized.

Republish