On January 1, 1953, during the largest polio epidemic ever recorded in Brazil, the Correio da Manhã newspaper reported: “There is no epidemic of infantile paralysis in Rio.” Cases, however, were multiplying—450 had already been recorded, with 27 deaths, since June of the previous year—yet the city’s Department of Health assured the public that the numbers were “strictly within the usual incidence.” On January 23, the newspaper again denied the epidemic and, jokingly, claimed that polio was a “cold-weather disease,” an “epidemiological element” that could not exist in Rio’s summer.

Denying the severity of the epidemic was a strategy to avoid panic. Another way of reassuring the public was to promote ineffective preventive measures, such as fumigation in the interior of São Paulo, even though it was already known that infection could be transmitted via the fecal-oral route. “Even flies were seen as a cause of the disease. It was believed that they landed on the homes of the poor and carried it to the homes of the rich during the great epidemics of 1916 in the United States,” explains Dr. Dilene Nascimento, of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ) and editor of the book A história da poliomielite (The history of poliomyelitis; Garamond, 2010).

At that time, there was still no effective way to prevent acute neurological infection, which could quickly progress to irreversible paralysis, especially of the legs, or to death when it affected the muscles responsible for swallowing or breathing. Racing against time, some victims with paralyzed respiratory systems could be kept alive by the so-called iron lung, a metal cylinder with a pump that forced air in and out of the lungs.

Nara / Wikimedia CommonsSabin (left) and Salk in 1958, among others who contributed to the development of the polio vaccineNara / Wikimedia Commons

The disease primarily affected children under the age of five—hence the term “infantile paralysis”—but it also struck adults. In 1921, it paralyzed the legs of US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882–1945), then 39 years old. In 1943, it claimed the life of Getúlio Vargas Filho, the 23-year-old son of President Getúlio Vargas.

In an atmosphere of fear and urgent demand for protection against the disease, the announcement that New York virologist Jonas Salk (1914–1995) had developed a safe and effective vaccine—injectable and made with inactivated (killed) virus—turned him into a global celebrity. Fame was inevitable, but he renounced the fortune he might have earned from royalties. When asked who would own the patent, he reportedly replied: “The people, I would say. There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?”

On the very day the positive trial results were announced—April 12, 1955—Salk’s vaccine was licensed. Two years later, annual cases in the United States had fallen from 58,000 to 5,600, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

In 1961, a new immunization option became available: the oral vaccine, developed from live attenuated virus by Polish-born American microbiologist Albert Sabin (1906–1993). He, too, chose not to patent his invention.

At that time, polio was paralyzing about 1,000 children per day in 125 countries, according to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). “The oral polio vaccine had a major impact on eradicating the disease. It reduced cases caused by the wild virus by more than 99.9%,” says epidemiologist Ligia Kerr of the Federal University of Ceará School of Medicine (FM-UFC). “The drops are easy to administer, and vaccinated children spread the virus to other children, which Salk’s vaccine does not do because it uses a killed virus. However, the attenuated vaccine virus can mutate, especially in areas with low vaccination coverage, leading to new cases of polio.”

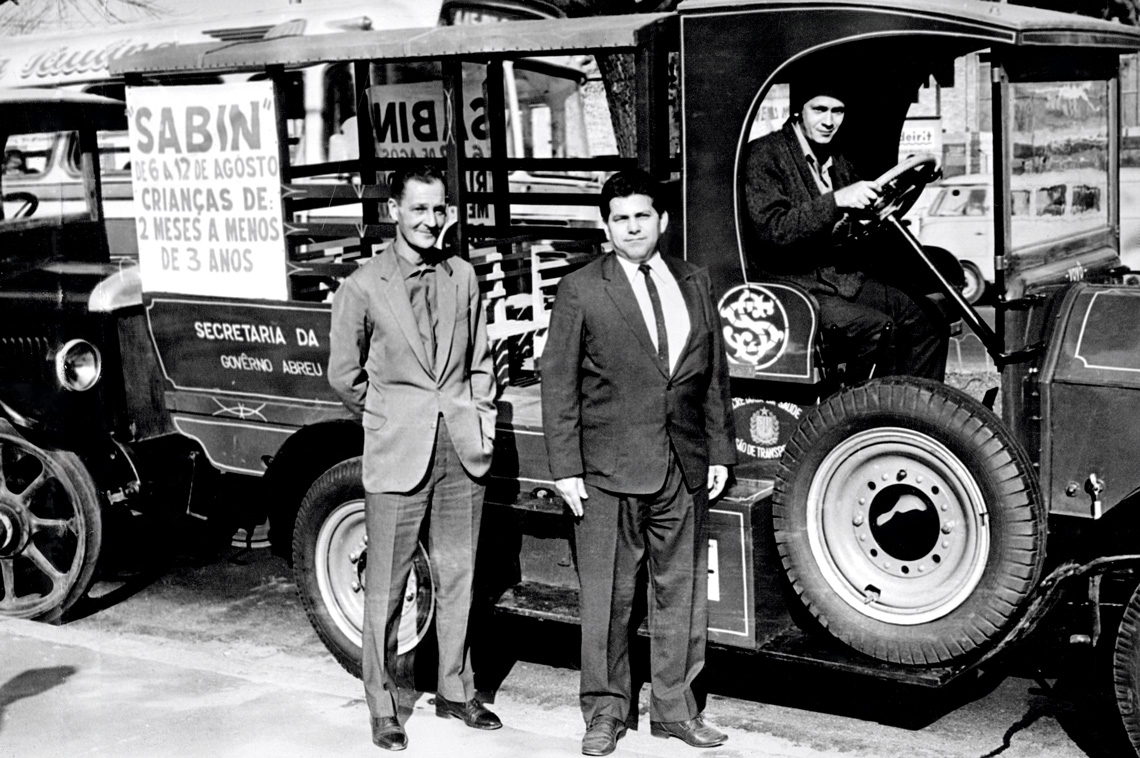

Folhapress Car used in the polio vaccine campaign in São Paulo, 1969Folhapress

The march of fear

The development of a “safe, effective, and potent” vaccine—as Salk’s was advertised—was the culmination of decades of research and discovery, dating back to the first records of the disease in the eighteenth century. Evidence suggests that polio affected humanity as early as 1350 BC (see chronology in the online version of this article), but it was not until 1789 that British physician Michael Underwood (1737–1820) produced the first clinical description of the disease, characterizing it as “weakness of the lower extremities.”

In its epidemic form, polio took hold at the turn of the nineteenth to the twentieth century. The first major outbreak occurred in the United States in 1916, with more than 27,000 cases and 6,000 deaths. A year later, Brazilian physician Francisco de Salles Gomes Júnior (1888–1972), then director of the São Paulo Health Service, described an outbreak in Americana, in the interior of São Paulo State. He believed the virus had been imported from the United States, given the historical ties between the area—then known as Vila Americana—and that country. This epidemic led to the enactment of Law No. 1,596, which made polio a notifiable disease in the state.

In his novel Nemesis, American writer Philip Roth (1933–2018) portrays the panic caused by polio. Families moved to the countryside to escape the disease, and children were forbidden from using public swimming pools, going to the movies, riding buses, or even borrowing books from the library. As fear spread, scientific—and political—efforts to develop a vaccine intensified. The public also mobilized, joining the fundraising campaign launched by Roosevelt in 1938, the March of Dimes, donating 10-cent coins (dimes) to support polio research.

The real prospect of a vaccine became more concrete in 1949, when researchers John Enders (1897–1985), Thomas Weller (1915–2008), and Frederick Robbins (1916–2003) succeeded in cultivating the poliovirus in cultures of different types of tissue. Their article, published in Science in January 1949, earned them the 1954 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. This breakthrough paved the way for the Salk and Sabin vaccines.

Collection of the Butantan Institute / Emílio Ribas Public Health Museum Posters supporting the campaigns (from 1971, left; undated, right)Collection of the Butantan Institute / Emílio Ribas Public Health Museum

National campaigns

In Brazil, the Salk vaccine arrived in 1955, the same year it was licensed in the United States, first in São Paulo, likely because the city had a more organized health system than Rio de Janeiro, where it began to be administered the following year. At first, only a few children received it.

Kerr was among the children who did not have the opportunity to be vaccinated at that time, which left his right leg and part of his left leg affected: “I contracted polio in 1957, at the age of 1, when the vaccine was still rare in Brazil.” It was only with Sabin’s vaccine that immunization began to spread worldwide. Even then, access was limited in the early years. “Only a few pediatricians bought it and administered it in their offices,” recalls Nascimento.

As soon as the United States licensed Sabin’s oral vaccine, the Ministry of Health created a commission to evaluate which option would be adopted in Brazil. “They concluded that it would be the oral one,” reports Nascimento. The low cost and ease of administration weighed heavily in that decision.

The first mass vaccination campaign was carried out in Santo André, in Greater São Paulo, on July 16, 1961, with the goal of immunizing 25,000 children, including those from neighboring municipalities. In a February 2011 article in Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, Nascimento notes that these first initiatives “were characterized more by discontinuity, due to problems with vaccine supply and distribution, than by expanded vaccination coverage.”

Paulo Pinto / Agência BrasilChildren receive the Sabin vaccine in São Paulo, as part of a national mobilization against polio in 2024Paulo Pinto / Agência Brasil

It was only in the 1980s that national polio vaccination campaigns organized by the Ministry of Health began. Cases declined rapidly, from 1,290 in 1980 to 122 in 1981. In 1989, the year of the last polio cases in Brazil, there were only 35, the final one recorded in Sousa, Paraíba.

In the early years of National Vaccination Day, vaccines were imported from European laboratories. Production later began at Bio-Manguinhos, FIOCRUZ’s drug manufacturing unit, through a technology transfer agreement signed in 1980 between the governments of Brazil and Japan. Biologist Rosane Cuber, director of Bio-Manguinhos, explains that because the manufacture of the viral concentrate proved unfeasible from both economic and technical standpoints, it was decided to formulate the vaccine using imported viral concentrate. According to her, Bio-Manguinhos produced 691 million doses of the trivalent vaccine (for viral types 1, 2, and 3) between 1984 and 2014, and 212 million doses of the bivalent vaccine (types 1 and 2) from 2015 to 2024. Through a partnership initiated in 2011 with the French pharmaceutical company Sanofi, it also produced 145 million doses of inactivated-virus vaccine. At that time, the vaccination schedule consisted of three doses of the injectable vaccine (at 2, 4, and 6 months) and two booster doses of the oral vaccine.

The strategy of National Vaccination Days adopted in Brazil became a model for other countries, and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) recommended it for the eradication of the disease in the Americas, achieved in 1994. Today, however, this achievement is under threat. According to Kerr, from UFC, there is an imminent risk of polio returning to Brazil: “Polio and measles vaccines, for example, require 95% coverage to control the disease, but in 2024 we were around 70%, with significant regional variation.”

She warns that the world has seen a decline in childhood vaccination over the past 30 years: “Because they no longer see cases, people mistakenly believe the disease has disappeared.” In Brazil, she argues, problems such as vaccine shortages in health centers, government communication failures, and misinformation may have hindered compliance with vaccination schedules, particularly among lower-income groups.

“It would be important to take health center teams into schools and large companies,” says pharmacist-biochemist Wasim Aluísio Prates-Syed, a doctoral student at the Institute of Biomedical Sciences at the University of São Paulo (ICB-USP) and a member of União Pró-vacina, an initiative of the Institute of Advanced Studies at USP to combat vaccine misinformation.

Collection of the Butantan Institute / Emílio Ribas Public Health MuseumZé Gotinha participates in a vaccination campaign in Osasco (SP), undatedCollection of the Butantan Institute / Emílio Ribas Public Health Museum

Joining global efforts to eradicate the disease, in November 2024 the federal government announced a change to the polio vaccination schedule, in line with a WHO recommendation: replacing the oral live attenuated virus vaccine with the injectable inactivated virus vaccine.

Previously, three doses of the injectable vaccine were administered at 2, 4, and 6 months of age, followed by two booster doses of the oral vaccine at 15 months and 4 years. Under the new schedule, only one booster dose will be given at 15 months, also with the injectable vaccine. The goal is to reduce circulation of the live attenuated virus in areas with low vaccination coverage and to minimize the small but real risk that the virus could undergo genetic mutations and regain virulence. In 2024, several African countries reported cases of the disease caused by circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus.

The replacement of drops with injections is not expected to retire Zé Gotinha, the mascot of national vaccination campaigns. Created in 1986 by Minas Gerais artist Darlan Rosa, then working at the Ministry of Health, the character was originally designed to popularize polio campaigns but eventually became a symbol of vaccination more broadly.

“I never associated Zé Gotinha only with the oral polio vaccine. He is the mascot for vaccines, and I don’t know of any other like him in the whole world,” says Prates-Syed proudly, who even has a tattoo of Zé Gotinha on his arm. Nascimento, meanwhile, emphasizes that the fight against polio has also strengthened vaccination against other preventable infectious diseases. The national immunization schedule now includes 19 vaccines to be taken from birth.

The story above was published with the title “Victory under threat” in issue 354 of August/2025.

Scientific articles

CAMPOS, A. L. V. de et al. A história da poliomielite no Brasil e seu controle por imunização. História, Ciências, Saúde ‒Manguinhos. Vol. 10, no. 2. Mar. 9, 2004.

NASCIMENTO, D. R. do. As campanhas de vacinação contra a poliomielite no Brasil (1960-1990). Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. Vol. 16, no. 2. Feb. 2011.

ENDERS, J. F. et al. Cultivation of the lansing strain of poliomyelitis virus in cultures of various human embryonic tissues. Science. Vol. 109. no. 2822. Jan 28, 1949.

Books

ROTH, P. Nêmesis. Trad. Jorio Dauster. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2011.

NACIMENTO, D. R. do (ed.). A história da poliomielite. Rio de Janeiro: Garamond, 2010.