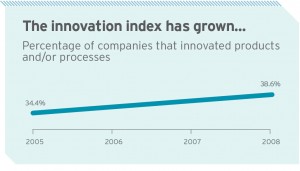

The results of the fourth Technological Innovation Survey (Pintec), announced at the end of October, showed that the number of Brazilian companies involved in innovations from 2006 to 2008 had increased. However, the results also showed that structural problems persist, such as the insignificant interest of the private sector in investing in R&D and a limited contingent of researchers working in companies. The corporate innovation index, which had stood at 34.4 percent in the 2003 to 2005 period, rose to 38.6 percent in the 2006 to 2008 period. In other words, out of the 106,862 companies interviewed for the study, 41.3 thousand had created a new product, or adopted a new or significantly improved process during the period analyzed by the study. The Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), which has conducted Pintec since 2000, collected data on 100,496 industries and 6,326 companies from selected sectors of the services industry and on 40 companies dedicated to R&D.

The results of the fourth Technological Innovation Survey (Pintec), announced at the end of October, showed that the number of Brazilian companies involved in innovations from 2006 to 2008 had increased. However, the results also showed that structural problems persist, such as the insignificant interest of the private sector in investing in R&D and a limited contingent of researchers working in companies. The corporate innovation index, which had stood at 34.4 percent in the 2003 to 2005 period, rose to 38.6 percent in the 2006 to 2008 period. In other words, out of the 106,862 companies interviewed for the study, 41.3 thousand had created a new product, or adopted a new or significantly improved process during the period analyzed by the study. The Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), which has conducted Pintec since 2000, collected data on 100,496 industries and 6,326 companies from selected sectors of the services industry and on 40 companies dedicated to R&D.

A discouraging fact is that growth, driven mostly by the economic development in the period, was not followed by a proportionately higher effort of the private sector in internal R&D activities, which are the ones that usually generate innovations that increase competitiveness and help companies win new markets. The 2008 Pintec shows that the enterprises had invested approximately R$54.1 billion in innovative activities (vs. R$41.3 billion in 2005), of which R$15.2 billion had been invested in internal R&D activities (vs. R$10.4 billion in the previous survey). However, corporate spending on internal R&D actually increased by 23 percent, when the data of the 2008 and 2005 research studies is compared using values adjusted by the IGP-DI price index in the 2008 survey.

A discouraging fact is that growth, driven mostly by the economic development in the period, was not followed by a proportionately higher effort of the private sector in internal R&D activities, which are the ones that usually generate innovations that increase competitiveness and help companies win new markets. The 2008 Pintec shows that the enterprises had invested approximately R$54.1 billion in innovative activities (vs. R$41.3 billion in 2005), of which R$15.2 billion had been invested in internal R&D activities (vs. R$10.4 billion in the previous survey). However, corporate spending on internal R&D actually increased by 23 percent, when the data of the 2008 and 2005 research studies is compared using values adjusted by the IGP-DI price index in the 2008 survey.

However, the proportion of total spending on innovative activities to net sales revenues of the companies shows that the figures are stable, with a slight drop in comparison to the percentage figures reported in the 2005 Pintec. The proportion slid from 3 percent in 2005 to 2.9 percent in 2008. As for expenses related to internal R&D activities, the ratio rose slightly, up from 0.77 percent in 2005 to 0.8 percent in 2008. “It has been expected that the priority given to innovation by public policies, associated with economic growth, would influence the indicators. But the effort of the private sector in innovation is still relatively insignificant in Brazil,” says Sérgio Robles Reis Queiroz, a professor at the Department of Scientific and Technological Policies of the Geosciences Institute at the State University of Campinas (Unicamp) and former assistant secretary of Science, Technology and Economic Development of the State of São Paulo. In 2008, Brazil invested 1.09 percent of its GDP in R&D; the private sector accounted for 44 percent of this figure. In Germany and in the United States, despite the global economic crisis, R&D spending equaled 2.64 percent and 2.77 percent of the respective GDPs, private sector companies accounting for more than two-thirds of the total.

Elite

Elite

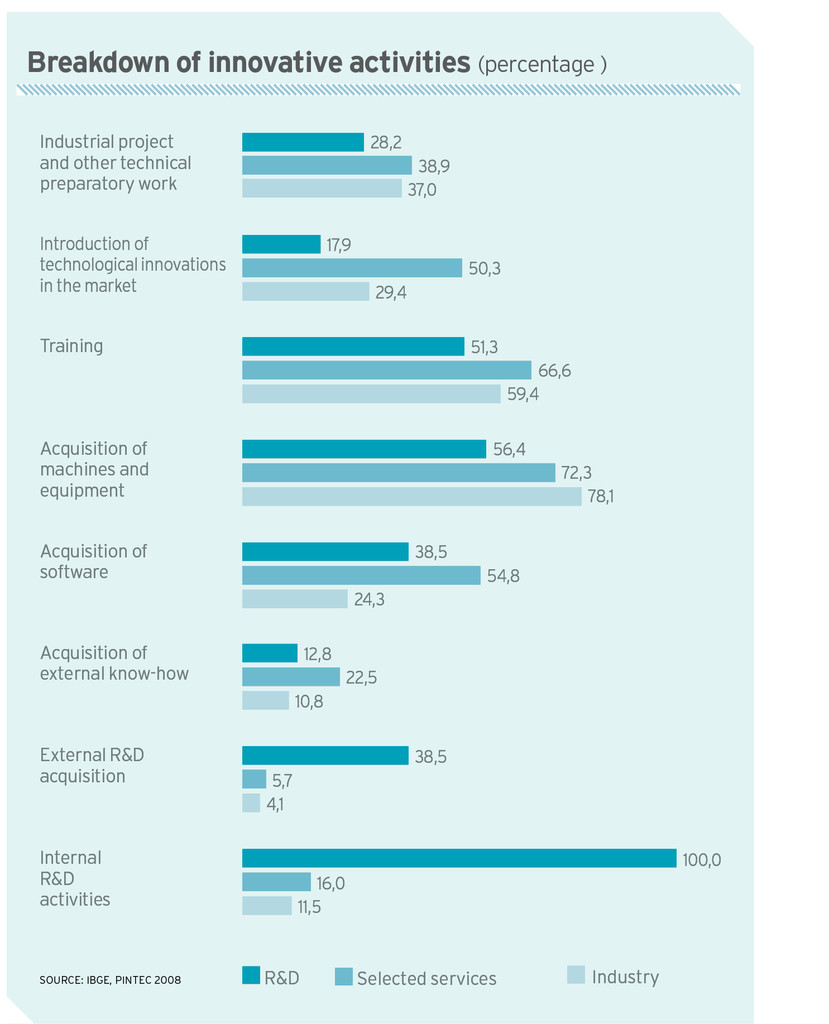

The research shows that only some elite industries can be considered innovative, in the real sense of the word. Of the 100,496 industries surveyed, 38,299 implemented a new or significantly improved product and/or process in the 2006 to 2008 period. Of this number, only 3,232 companies developed innovative products or services for the domestic market and a mere 267 enterprises created innovations for the global market. In most cases, the innovation benchmark was merely the standard in effect at the company itself, which implies limited gains, even if they make a difference in revenue. Furthermore, for most companies, the innovation standard is still based on access to technological know-how by incorporating machines and equipment. According to Pintec 2008, 77.7 percent of the total number of innovating enterprises considered the acquisition of machines and equipment as important to developing innovations, vs. 80.6 percent of the companies in the 2005 survey. Training was considered the second most important element (59.7 percent in 2005 and 59.9 percent in 2008). A new fact was the percentage increase of firms that consider it important to acquire software: 16.6 percent in the 2003 to 2005 period vs. 26.5 percent in the 2006 to 2008 period.

Internal R&D activities were considered important by 11.5 percent of the industries, 16 percent of the services firms and 100 percent of the R&D companies. “The main issue is not to know how many companies engage in innovation, but rather the actual result obtained from the dedicated resources,” says economist João Furtado, a professor at the Polytechnic School of the University of São Paulo (USP) and FAPESP’s coordinator of technological innovation. “Buying a new machine rarely helps the company gain new markets or sell products at higher margins, those for which clients are willing to pay more because they perceive a significant benefit.” In the case of the Brazilian industry, spending on machines and software is twice as high as investments in internal and external R&D. In Spain, in contrast, the acquisition of machines accounts for only 40 percent of spending on internal and external R&D, while in Germany, these acquisitions account for one half of the spending.

Agriculture

In João Furtado’s opinion, other elements should be taken into account regarding Pintec. He points out that the survey broadened the concept of innovation by incorporating organizational and marketing elements, which increased the scope of companies rated as innovative. This was in line with changes in international parameters. He says that agricultural technology, a sector in which Brazil is renowned as being on the forefront, is not surveyed by the Pintec. “Agriculture has natural synapses, people who, because of their origin and life styles, communicate among themselves or form communities based on the application of knowledge. This leads to a succession of small innovations that are constantly being disseminated,” he states. “Anyway, we have to agree that we are still far from an ideal situation, in terms of scope and intensity of innovation.”

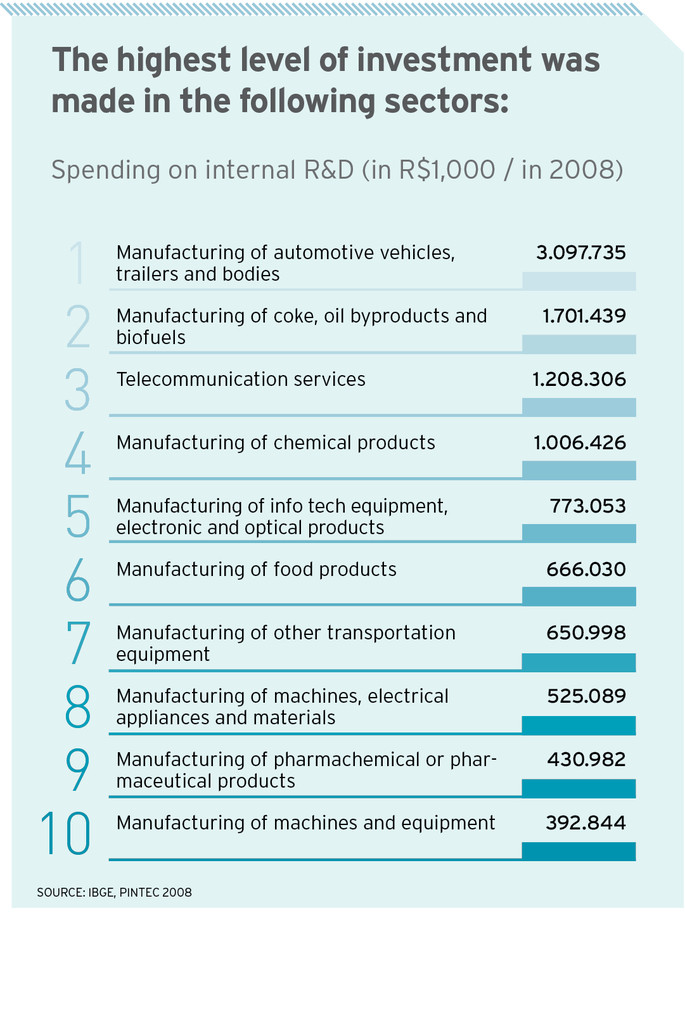

An analysis of the data reveals unequal performance in different sectors. Most of the growth occurred in the processing industry. The increase in expenditure on internal R&D activities, – restating the 2005 values using the IGP-DI price index – concentrated on the following sectors: automaking (R$1.1 billion), oil and biofuels (R$0.57 billion) and the manufacturing of chemicals (R$0.41 billion). In the services industry, the highest increase was in telecommunication (+ R$0.68 billion), but there was a significant reduction in the info tech sector (- R$0.4 billion). The innovative impetus of the automakers is a tendency that had already been observed in previous surveys. “Brazil has a tradition of innovation in the field of mechanics, while in the developed countries the leading sectors are related to info tech and pharmaceuticals,” says Sérgio Queiroz. In the case of oil and biofuel, the Petrobras investments and the development of alternative sources, such as ethanol, explain the growth.

An analysis of the data reveals unequal performance in different sectors. Most of the growth occurred in the processing industry. The increase in expenditure on internal R&D activities, – restating the 2005 values using the IGP-DI price index – concentrated on the following sectors: automaking (R$1.1 billion), oil and biofuels (R$0.57 billion) and the manufacturing of chemicals (R$0.41 billion). In the services industry, the highest increase was in telecommunication (+ R$0.68 billion), but there was a significant reduction in the info tech sector (- R$0.4 billion). The innovative impetus of the automakers is a tendency that had already been observed in previous surveys. “Brazil has a tradition of innovation in the field of mechanics, while in the developed countries the leading sectors are related to info tech and pharmaceuticals,” says Sérgio Queiroz. In the case of oil and biofuel, the Petrobras investments and the development of alternative sources, such as ethanol, explain the growth.

Economist André Tosi Furtado, a professor at the Science and Technology Policies Department of Unicamp, says that more sectors have advanced than slipped back, as seen in analyses of historical series of spending on internal R&D as a percentage of firms’ net sales earnings . “The data shows that the innovation performance of sectors linked to commodities, such as food products – a major industry in Brazil – has improved, as has the innovative performance of oil refining, telecommunication, automakers and even the pharmaceutical industry. Even though the latter, in Brazil, doesn’t make a huge research and development effort, it has been driven in this respect by industrial and sector policies related to the production of generic drugs,” says André Furtado. “Some industries are declining in this respect, such as the machines and equipment industry, which has been adversely affected by the foreign exchange policy and by a deluge of imports. The manufacturing of transportation materials, including the aeronautical industry and electric equipment, has also declined. These are warning signs, because some of these industries are strategic,” he states. Although he says that structural problems still persist in Brazilian companies, he emphasizes that, if the economic situation maintains its current status, the impact will continue to be positive in the long term. “Our R&D effort in industry is still five times lower than in the OCED member countries, but we are moving forward and we hope that this will continue,” he states optimistically.

Personnel shortage

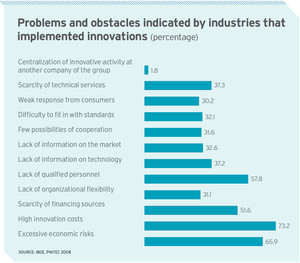

“Pintec 2008 mapped companies” problems in terms of the innovation process. Concerning the industries, the chief obstacles are high innovation costs (73.2 percent ), excessive economic risks (65.9 percent ), shortage of skilled labor (57.8 percent ) and a lack of financing sources (51.6 percent ). A comparison with Pintec 2005 shows that the shortage of skilled labor now carries more weight and the lack of financing resources is less important. This data is in line with one of the conclusions reached by the Paulista Science, Innovation, and Technology Conference held at FAPESP in May. This conclusion states that the shortage of qualified human resources is starting to affect the growth of São Paulo enterprises.

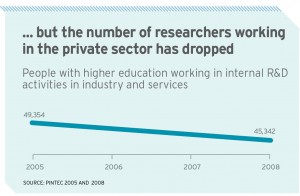

An intriguing and worrisome piece of information found in Pintec 2008 was the drop in the number of researchers working in companies: 35 thousand researchers worked in companies in 2000; this rose to more than 40 thousand in 2003, to 50 thousand in 2005, but dropped to 45 thousand in 2008. In countries such as Germany and South Korea, the army of researchers working for enterprises totals 180 thousand people. In Japan, 492 thousand. In the United States, more than 1.1 million. “This is a cause for great concern, because the strategies and policies are designed to bring more researchers into firms and this number has not even remained constant: it dropped by 10 percent in the period,” pointed out Carlos Henrique de Brito Cruz, the FAPESP scientific director. “This problem has to be thoroughly understood. We must analyze these indicators frequently to be able to readjust public policies accordingly.”

An intriguing and worrisome piece of information found in Pintec 2008 was the drop in the number of researchers working in companies: 35 thousand researchers worked in companies in 2000; this rose to more than 40 thousand in 2003, to 50 thousand in 2005, but dropped to 45 thousand in 2008. In countries such as Germany and South Korea, the army of researchers working for enterprises totals 180 thousand people. In Japan, 492 thousand. In the United States, more than 1.1 million. “This is a cause for great concern, because the strategies and policies are designed to bring more researchers into firms and this number has not even remained constant: it dropped by 10 percent in the period,” pointed out Carlos Henrique de Brito Cruz, the FAPESP scientific director. “This problem has to be thoroughly understood. We must analyze these indicators frequently to be able to readjust public policies accordingly.”

The limited drive for innovation in companies is offset by increasing government support for innovative activities. Indeed, the percentage of innovative firms that resorted to at least one government source of funding has increased. In this respect, the percentage figure was 18.8 percent of the total number of firms in 2005 and rose to 22.3 percent in 2008. Thus, in this period, 9.2 thousand enterprises resorted to some kind of federal government funding to produce innovations. The main tool used by industry’s innovative firms was credit for the purchase of machines and equipment (14.2 percent ); the least frequently used tool was the recently created economic subvention instrument (0.5 percent ) and the funding for R&D and technological innovation projects in partnership with universities or research centers (0.8 percent ). In relation to tax incentives regulated by R&D and Technological Innovation laws and by the “Lei do Bem”, a set of tax incentives for R&D to boost innovation, the percentage of innovative industrial companies that resorted to these tax benefits was 1.1 percent ; most of these firms had more than 500 employees, and accounted for 16.2 percent of the said percentage .

Republish