How do universities and companies in Brazil work together to generate knowledge? Two researchers from the School of Economics, Business, and Accounting of the University of Sao Paulo at Ribeirão Preto (FEA-RP-USP) attempted to answer this question by examining which factors were associated with interaction between companies and 240 public university laboratories in São Paulo State. Some of the study’s conclusions, published in December 2024 in the journal Science and Public Policy, confirmed the results of similar studies conducted in other countries: Compared with laboratories that are less involved with companies, those that have more engagement stand out for their skills in prospecting and attracting private initiative partners, have access to advanced equipment, and have more permanent researchers to support joint projects. They also receive more support from their departments to facilitate cooperation.

However, there are peculiarities in Brazil, one of which is that the senior level of faculty staff does not interact significantly with industry, an aspect that is more readily observed in the US and Europe with the gradual formation of collaboration networks over professors’ careers. Among the 240 São Paulo State laboratories analyzed, only 55 were led by tenured professors, the highest level in the public academic career, while 114 were led by lecturers or associate professors, and 71 were led by fellow professors. According to the research coordinator, FEA-RP-USP researcher Alexandre Dias, this outcome highlights the marked differences between the science, technology, and innovation (STI) systems in Brazil and those in more developed countries.

“In public Brazilian universities, research and extension are indivisible, and academics at their highest career level usually get closely involved in the management of their units. The predominance of public research funding, the rewards system, and the criteria by which faculty staff are assessed for career progression do not contribute to individual performance aligned with interaction with the industrial sector,” says the researcher, who conducted the survey with Leticia Ayumi Kubo Dantas; he advised on her master’s dissertation, defended in 2023. The two are part of the Center for Research in Innovation, Technological Management, and Competitiveness at FEA-RP-USP.

Geraldo Falcão / Petrobras Inspection laboratory at the Petrobras Research Center: Legislation boosts collaborationsGeraldo Falcão / Petrobras

The key objective of the study was to analyze the degree of “academic engagement” among research laboratories in Brazil. This concept, proposed in 2013 by Markus Perkmann of the UK’s Imperial College London Business School, brings together a set of formal and informal activities that modulate the interaction between universities and the business world. “For a long time, researchers have striven to understand what drives the commercialization of technologies and academic entrepreneurship as phenomena to analyze university–corporation interaction. In the last decade alone, interest has also grown in investigating other channels by which links are forged between universities and companies,” Dias explains.

Laboratory data from seven institutions were analyzed—state-level institutions São Paulo State University (UNESP), the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), and the University of São Paulo (USP), as well as the federal universities of São Paulo (UNIFESP), São Carlos (UFSCar), and ABC (UFABC), and the Aeronautics Technology Institute (ITA), whose leaders agreed to complete an online questionnaire. In terms of knowledge areas, 20% of the laboratories worked with assorted engineering disciplines—15.8% health sciences, 14.5% biological sciences, 12.5% exact and earth sciences, and 9.6% agrarian sciences; additionally, 27.5% operated across multiple areas.

The research facilities were separated into three categories: The largest group, with 112 laboratories, presented minimal, sporadic involvement with companies. The second group comprised 84 laboratories and demonstrated partial engagement with private initiatives. The third group, consisting of 44 laboratories, stood out for its interaction with companies through different channels: collaborative research (52.3%), research contracts (40.9%) and the expansion of facilities funded by private sources (34.1%). These laboratories also participated in informal interactions, such as postgraduate student training in industry projects (15.9%) and consultancy services (22.7%).

The economic value of equipment in these highly engaged laboratories, along with the number of permanent researchers, was found to be three times greater than that in laboratories interacting minimally with companies. Support from departments with which the laboratories are associated was more significant among those engaging significantly: 32% stated that they received sufficient support, compared with 13.4% of those having minimal engagement and 22.6% in the intermediate category. According to Leticia Dantas, the lead author of the study, the research demonstrates the importance of enhancing university laboratories and ensuring a robust structure and larger teams. “This not only boosts academic engagement but also makes laboratories more attractive for partnerships with industry, multiplying the impact of research in the productive sector,” she says.

Engaged laboratories interact with companies through multiple channels

Economist Eduardo da Motta e Albuquerque, of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) and a researcher at the university’s Center for Development and Regional Planning (CEDEPLAR), who did not participate in the study, agrees that one of the takeaways of the article lies in demonstrating the importance of enhancing research laboratories in the Brazilian university system. “Interaction attracts funds to laboratories and has an impact on the quality of research, bringing new themes for investigation to the university,” says Albuquerque, a specialist in the formation of innovation networks and the forging of links between universities and companies (see Pesquisa FAPESP n° 234).

“It would also be interesting to widen the survey and find out which industrial segments interact most with the laboratories,” he says. He would bet that there are noteworthy interactions occurring in the agricultural sector, given its economic importance for Brazil, but very little going on with the large pharmaceutical companies, which base their research at overseas headquarters. Albuquerque sees a warning sign in an outcome presented in the article, according to which no correlation was found between the engagement of laboratories with companies and the support provided by the Technological Innovation Centers—offices created under the 2004 Law of Innovation—at public science and technology institutions to manage intellectual property and lend support to university–industry interaction. “The country invested heavily to set up these centers; maybe it’s time to have another look at their function,” he says.

The relationship between universities and companies needs to overcome a series of obstacles, says chemist Elson Longo, an emeritus professor at the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar) and director of the Center for the Development of Functional Materials (CDMF), one of the Research, Innovation, and Dissemination Centers (RIDC) funded by FAPESP. “Some of the interaction comes through consultancy services offered by researchers to companies. There needs to be more ambitious cooperation to obtain new knowledge and develop innovative products,” he says, giving examples of projects set up by the RIDC in recent decades with the steelmaking and ceramics and cladding industries, which brought changed production methods and productivity gains—the institution currently has partnerships for the development of inputs for cosmetics factories. He also draws attention to the low levels of interest among multinationals in collaborating with Brazilian groups, as a rule preferring to use research and development (R&D) structures at their headquarters.

Emilio Carlos Nelli Silva, of the Department for Mechatronics and Mechanics Systems at the Polytechnic School of the University of São Paulo (USP), sees marked differences between interaction among universities and companies in Brazil and this type of interaction in other countries. “The relationship is more fluid in the United States because companies hire PhDs to work in their R&D centers, and liaising with university groups is done through them. Here in Brazil, as there are still very few PhDs in companies, other actors are involved, and sometimes, there is a lack of understanding that research can come up against obstacles,” he adds.

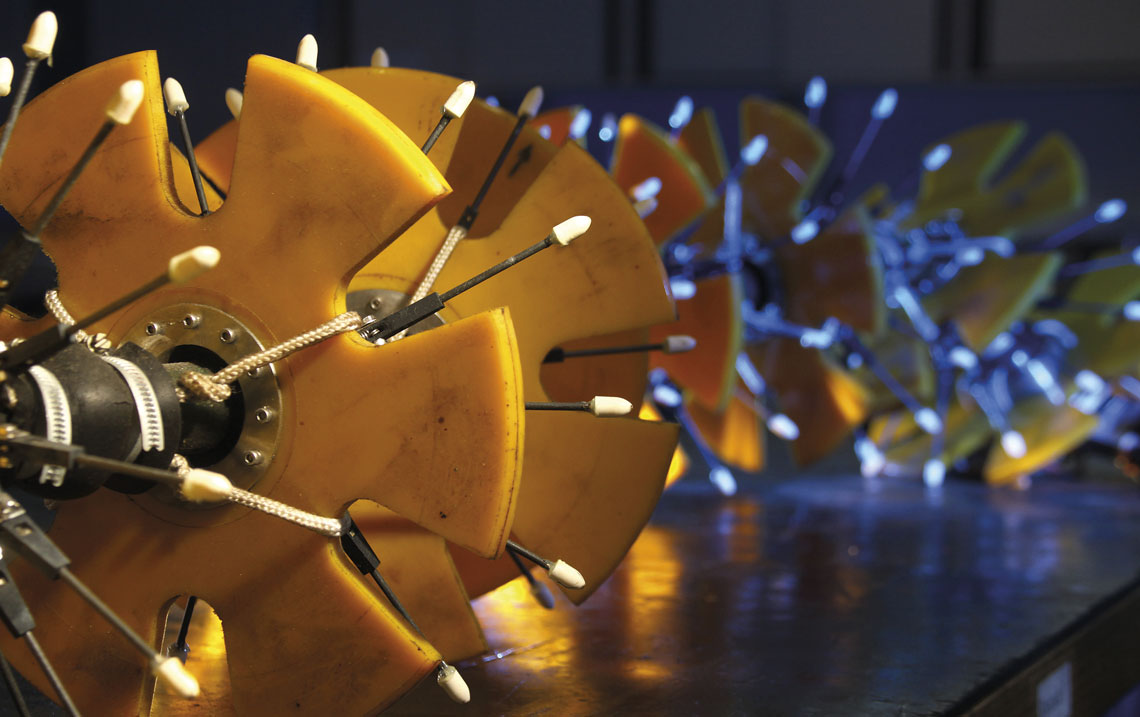

Léo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESPLaboratory for Fuel Cells and Reactive Conversion at POLI-USP: Innovation and greenhouse gasesLéo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESP

Funding is another difference. “It’s not our culture here to invest risk capital in promising research, although in certain areas like petroleum and electricity, companies have a legal obligation to invest in R&D, and this creates good opportunities for research partnerships,” he says. Silva is the vice director of the engineering program at the Greenhouse Gases Innovation Research Center (RCGI), one of the Applied Research Centers/Engineering Research Centers funded by FAPESP in partnership with companies—in this case, Shell. The program offers nonreimbursable funds for corporate projects, requires the counterpart funding to be equal to or to exceed the public investment, and engages university research groups of excellence. “The centers create new paradigms for collaboration between universities and companies and bring clear benefits for society.”

According to physicist Carlos Frederico de Oliveira Graeff, of the School of Sciences at UNESP’s Bauru campus, liaising between universities and industry has improved, but there are still things to work out. “Industry doesn’t always get solutions for its problems from academia, just like researchers who make efforts to interact don’t necessarily find companies interested in their expertise,” he says. Graeff runs the Laboratory for New Materials and Devices, which is one of the research facilities participating in the FEA-RP-USP study and is classified among the laboratories with high levels of engagement. The facility, which is currently seeking new materials for use in electronic devices such as solar cells and transistors, is cooperating with two companies: One is a Singapore-based startup seeking uses for the discarded waste of industries that use flies as raw material to produce animal protein. The challenge is to make use of large volumes of discarded fly exoskeletons (outer shells), which are rich in the biomolecule melanin. Graeff’s group is looking at possible applications for the compound in batteries and capacitors because of its potential for storing energy. The other is a Brazilian company, to which the laboratory transferred useful technology for the production of perovskite solar cells, developed as part of a project supported by Petrobras.

Graeff believes that interactions could be more gainful if Brazil had wider access to multiuser platforms and analytical centers that company researchers could call upon. “Startups need cutting-edge equipment to develop products, and they don’t often have the funds to acquire it,” says Graeff, the former coordinator of Strategic and Infrastructure Programs at the FAPESP Scientific Department. The physicist also considers it pertinent to expand operations at research institutions working with applications at an intermediate level of technological maturity, which still require effort and investments to take a product to market. “The Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA) performs this function in agribusiness, and the National Service for Industrial Training (SENAI) has reached out to many different industrial segments through its Innovation Institutes,” he says. Graeff also highlights the model used by the FAPESP Science Centers for Development (CCD), which bring together researchers from state-level institutes, universities, companies, and government bodies in the quest for solutions to issues in society, from agricultural output to urban mobility. “These centers are mobilizing the system around mission-oriented research,” he concludes.

Republish