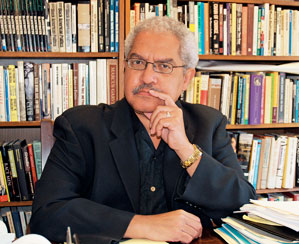

DAVID SHANKBONE/WIKIMEDIA COMMMONSManning MarableDAVID SHANKBONE/WIKIMEDIA COMMMONS

New York’s Columbia University (www.columbia.edu/cu/ccbh/mxp) has a site dedicated to black leader Malcolm X, who was assassinated on February 21, 1965, on a Sunday afternoon in Harlem. Malcolm X was killed in front of his pregnant wife, three of his four children and a crowd of hundreds of people who had been waiting to hear one more of his electrifying speeches. Malcolm, introduced to the rest of the world in a film directed by Spike Lee in 1992, would have turned 40 three months after that dramatic afternoon. The said site, named “The Malcolm X project at Columbia University,” is the result of persistent and ambitious work by professor Manning Marable, who teaches history and political science at Columbia. Professor Marable also founded the Research Institute for Afro-American Studies and is director of the Center of Contemporary Black History at Columbia.

In addition to building up a robust multi-media version of the Afro-American leader’s autobiography, the site’s stated objective is research and development of an extensive and thorough biography of this man, born in Ohio in 1925, whose father had been brutally murdered by the Ku Klux Klan when Malcolm X was still a child. In 2009, the research conducted by Marable is expected to result in the publication of the professor’s latest book: Malcolm X: a life of reinvention.

This 58-year old eminent Afro-American scholar, one of the most prominent members of the US’s academic community, who has already written 19 books, has not narrowed down his research work to one person. The Afro-American leaders of the past and the present and the long battle for civil rights for Afro-Americans have always been Marable’s focus, as shown by his book Living black History: how re-imagining the African American past can remake America’s racial future, published by Civitas Books in 2005.

Of course this focus includes the newly-elected President of the United States. Marable, in his newspaper column “Along the color line,” published in over 400 printed and virtual media in the USA, Canada, UK, Caribbean, and India, analyzed Barack Obama’s run for office from all angles and summoned his readers to help the Democratic candidate win the election. In January 2008, for example, Marable wrote: “We must unite our forces to support the election of Barack Obama, not only because he is progressive and fully qualified for the Presidency, but also because his campaign will force all Americans to overcome the centuries-old silence on racial prejudice that has created the profound abyss that permeates the democratic life of this nation.”

In October, Marable wrote an article that focused less on the campaign strategy and more on the well-designed political strategy devised by the group of moderate Afro-American leaders to which Obama belongs. In this article, Marable pointed out that the “debates on television finally woke up millions of perplexed white Americans to the fact that an Afro-American would probably be elected as the next president.” This stunning perception, he wrote, raised a wave of prejudice, thus demolishing the apparent neutrality surrounding the racial issue, which the country had apparently come to terms with in the last few years. In another article, also written in October, Marable argued that the democratic candidate’s economic platform would be able to revert some of the disastrous effects of the announced economic recession; in addition, he emphasized that voting for Obama was “absolutely necessary and essential for Afro American workers and for all Americans.”

On November 5, the day after Obama’s victory, Manning Marable explained during an interview to a New York radio show why he had been so sure that Obama would win the election, although he was astonished at how quickly such a victory had materialized at the start of the 21st century. One of the reasons was the rapid ethnic transformation of US society, whose population, in the next 30 years, will be comprised of blacks, mulattoes, Hispanics and Asian-Americans as the majority. The other reason was the solid background of the group of pragmatic Afro-American leaders, whose platform was at the center of the ideological spectrum rather than focusing on ethnic criteria, unlike the political platform of the black politicians who surfaced during the civil rights movements of the 1960’s and 1970’s. These pragmatic Afro-Americans were able to appeal directly to white Americans by focusing on a new project for the nation.

The following interview with Manning Marable was held at his office in a building on Amsterdam Avenue, not far from 119th Avenue, the site of Columbia University’s beautiful campus on New York’s Upper West Side. The interview was conducted on a cloudy afternoon, December 1, 2006. Having decided to publish this interview this year, I sent the professor some questions on Barack Obama’s victory and he answered by sending me copies of his articles on topics he found relevant. I chose to refer to some of them in the opening of this article and maintain the original interview conducted two years ago.

To begin, I would like to hear your comments on your research work on Malcolm X. Is this to result in a major biography?

Malcolm X was one of the most important Americans in the first half of the 20th century. More than any other black American, he represented the US’s black urban population. No other leader was more important than Malcolm X, who interpreted the politics and the rage of the Afro-Americans from the 1950’s to the 1970’s.

Why is he so significant?

In terms of Afro-American culture, Malcolm embodies two cultural metaphors or cultural expressions: the thief and the preacher. Malcolm’s life story encompasses the well-known 30-year period. In the forties, here in Harlem, he was known as “Detroit Red;” he was a young gangster then, involved in drug peddling and prostitution. He had been sent to jail at the age of 21 and remained in jail for seven years and seven months, during which he underwent a life transformation. He joined an obscure Islamic group, the Nation of Islam, led by Elijah Muhammad, who had preserved elements of traditional Sunni Islamism. In essence, however, the movement was a black, racist, defensive and deeply authoritarian movement, the product of a reaction to white supremacy in the United States. In this sense, the Nation of Islam movement simply inverted the theology of white supremacy, accusing the whites of being Satan and acclaiming the blacks as gods. This theology, permeated with elements of traditional Islam, spread throughout the poor black communities and the jail communities. At that time, Malcolm was confined in a Massachusetts State prison facility. Malcolm joined the group and when he was released from jail in August 1952, he achieved nationwide fame as the national spokesperson for Elijah Muhammad. In 1962 and 1963, he gained fame at US universities and on television as an angry black leader who was against racial integration and challenged the passive resistance advocated by Martin Luther King. Malcolm preached in favor of national black separatism and the creation of black companies and institutions wholly owned and controlled by blacks. He argued that blacks should build independent communities, entirely controlled by blacks, in cities in the United States. His desired objective was to provoke a racial separation identical to the one that split the Hindus and the Muslims when India and Pakistan were partitioned in 1947. The blacks would be given a certain number of US states in the South, from where all whites would be driven away and to which all Afro-Americans would move. This would result in total racial separation and genuine real political equality. Of course this was a racist view, created and devised by the blacks in reaction to white racism. In his later years, Malcolm did not accept or support this racist strategy. Yet during his early years, when Malcolm firmly believed in this view, he became a very influential figure in the media and in the press, to such an extent that the media exposure generated jealousy and opposition in the Nation of Islam.

In terms of opposing views, what was the relationship between Martin Luther King and Malcolm X like?

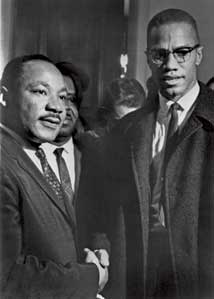

Both were frequently described as being on opposite ends of the spectrum, which, in my opinion, is incorrect. One must emphasize that Malcolm and King became close ideologically and politically. In his later years, in 1964-65, Malcolm X was totally against the Vietnam War. He was the first prominent American, and certainly the first Afro-American, to protest against the War in Vietnam, which he denounced as being a racist and imperialistic war. Malcolm also argued that Afro-Americans should go to the United Nations to present their situation as being a case of genocide and discrimination instead of defining our battle as simply a battle for civil rights. He argued that our battle was for human rights. Martin Luther King finally came to terms with Malcolm’s views: in 1967, he stated his opposition to the Vietnam War and agreed that the racial discrimination issue in the United States was a human rights issue. Malcolm X also launched a movement, later referred to as black power, which advocated building strong black institutions and the political control of big cities by blacks through the election of black mayors, state congressmen and senators. Martin Luther King also supported the black power concept, although the movement’s controversial slogan was not acceptable to him in many respects. King was not opposed to the idea of black representation and the election of black politicians. Thus, both men were coming closer in terms of personal and ideological characteristics, which I find very meaningful. In my latest book, Living Black History, the cover of which is a photograph of the two men together, I propose that Malcolm X be viewed as a human rights leader who evolved in political and ideological terms, especially in regard to racial discrimination and national liberation issues.

Was Malcolm’s stand more consequential than that of Martin Luther King in terms of the continuity of the history of blacks in the United States?

I don’t agree with this reasoning. In my opinion, their views were complementary, in terms of an analysis which challenges racial inequality and human injustice. I would say that both men approached the racial issue in slightly different ways, but their approaches represented the core voices in terms of the deconstruction and illegitimacy of white supremacy and racial injustice.

Your research studies focus on the history of blacks in the United States in the 20th century; however, you also focus on the 19th century and on earlier times. Could you summarize your point of view and outline a comparison with Brazil in this respect?

Certainly. I wrote a lot about this issue in my book Great wells of democracy: the meaning of race in American life, published in 2002, and in a previous book, African and Caribbean politics, published by Verso in London in 1987. In spite of the title, I do make references to Brazil. I propose that the history of blacks in Brazil and in the United States is both deeply similar and deeply different. The more significant similarities include the desire for freedom, for human rights and for human dignity by people of African descent, such battles transcending historical epics. This includes the slave trade, slavery itself, the emancipation of slaves in Brazil in 1888 and in the United States in 1865, and also the post-emancipation period, which is referred to as the Reconstruction in the United States. I also included the battle for freedom and equality in the 20th century. Therefore, there is a parallel in the sense that blacks suffered discrimination and had no access to education, housing or health care – all of which are elements that comprise the concept of human rights in the 21st century. However, there is a basic difference – indeed, there are several basic differences – between the two nations. The most important one is the fact that in Brazil the history of how the Brazilian State was shaped, including its political and civil society, is supported by a national awareness and a national identity that overcomes the awareness of race. In the United States, the nation was built on a clearly racial foundation.

What shows this?

I can give you an example. The first law approved by the US Government when Congress convened for the first time, that is, the most important law, contemplating immigration, approved in 1790, defined American citizenship as being the right only of free white people. In other words, to be considered a citizen of the state, the person had to be white, preferably male, and own property. Until 1920, women were not allowed to vote in the United States. Until 1790, all white males who owned properties had voting rights. From that time until 1830, all white men over the age of 21 could vote, regardless of income or property ownership. Race defined citizenship and the right to vote. Race defined who could be a member of a jury or submit evidence to a court. Blacks, if they were slaves, were not even allowed to submit evidence. In the United States, blacks were seen as property for nearly 250 years and most Afro-Americans did not vote in US presidential elections until 1968 because the civil rights law and the voting rights law were only approved in 1964 and 1965, respectively. Blacks had nominal voting rights and a minority was allowed to vote in the Northern and Midwestern States and on the West Coast, but blacks in the South were not entitled to these rights. They could not conduct, carry out or ensure their constitutional rights by voting. Therefore, the democratic state was pre-configured racially. In Brazil, however – and I am not minimizing the centrality or the importance of racial discrimination in the country – the situation was similar to that in Cuba; national awareness transcended the racial identity issue for the majority of Brazilians, even for the black Brazilians, who until very recently defined their own national identity outside a racial context. This never happened in the United States: you had to be white to be an American. Throughout most of US history, Afro-Americans were not even considered as people, subjects – we were considered as being property. This is the major difference. There is another difference which reinforces this.

ROBERT LLEWELLYN/CORBIS/LATINSTOCKMartin Luther King and Malcolm X convergeROBERT LLEWELLYN/CORBIS/LATINSTOCK

Could you specify?

The United States went through a Civil War and Brazil never did. This is extremely important historically. The Civil War was the major conflict in American history. Six hundred and fifty thousand Americans were killed and two million were wounded, out of a population of 38 million people. This shows how powerful the Civil War was. The focus concerned abolishing or maintaining slavery, whether half of the country should abolish slavery and the other half maintain it. At the end of the Civil War, blacks were technically free and were granted voting rights for a certain period of time, but this right was reverted twelve years later. Therefore, a war was necessary to abolish slavery. In Brazil, in the meantime, slavery had essentially become a dysfunctional economic institution. Even the slave owners began to clamor for some kind of abolition of slavery that would provide them with compensation. They observed the model in the West Indies, which was British, and saw how the plantation owners in the Caribbean were granted financial compensation; this made the Brazilians realize that owning slaves as a form of labor exploitation was neither as productive nor as competitive as the open market model. Economists already criticized Brazil in those times, especially the country’s dependence on slavery, attributing much of the country’s underdevelopment to it. This was not the case in the United Sates, where a war had to be fought to abolish slavery. Recollections of the conflict, even when mentioned on TV or in an American film, show how powerful the image of the South is in the Republican Party, even nowadays, when the Party has become the party of Dixie scum. All the white Southern racists, who hated civil rights, hated Martin Luther King, came together in the Republican Party in the 1960’s, 1970’s and 1980’s, under [Ronald] Reagan. This is the gist, the core of the Republican Party’s ideology. Anyone who wishes to understand Iraq has to understand Jim Crow’s segregation and anybody who wishes to understand Abu Ghraib needs to understand the lynching of blacks in the South. There is no difference: the same bestiality, the same racism, the hate, the demonizing and the discrimination that black Americans suffered is now being transferred by these racist bigots to all those who oppose them. They merely exported the same informality to the rest of the world. We’re talking about the same people. Trent Lott, a senator for Mississippi, is one of the architects of white supremacy; he is number two in the Republican Party’s power hierarchy. [The senator resigned in November 2007].

These historical differences between Brazil and the United States created different survival strategies among slaves and their descendants, as well as different cultural strategies. In Brazil, for example, where racism is not as open, the slaves’ need for religious expression and the need to protect themselves from government repression or persecution by the police (which went on for many years) led them to establish links between their original forms of worship and Catholicism, resulting in the creation of candomblé, a new Brazilian religion. Many years later, some groups began to incorporate some elements of Spiritism, which resulted in umbanda, a modified version of candomblé. In the United States, where racism was so open and the racial prejudice of the whites was expressed so forcefully, the blacks created their forms of religious worship within the white, Protestant religions. But whenever I go to a church in Harlem, I can see things in the singing and the body language that remind me of candomblé, for example.

You’re right; I’m familiar with candomblé. In a way, the use of the body and the voice was incorporated by the Pentecostals. Pentecostalism was founded – and flourished at first – in the Azusa Temple in San Diego, California, in 1905, by Afro-Americans. The Pentecostal, or sacred, faith places a lot of emphasis on the human being’s physical possession of God. So, the active body language, the singing, the excitement during the religious service differs a lot from what goes on in Episcopalian, Anglican or Methodist churches. Nowadays, millions of Americans are Pentecostal. But most of them are very conservative politically and do not join progressive associations or leftist organizations, trade associations or political organizations. They believe in “Rendering unto Caesar what is Caesar’s and unto God what is God’s.” The black Pentecostals, however, are radical and progressive in terms of how they express their faith and in terms of the content, because the black church was the only institution that the white slave masters allowed their slaves to be part of. The slaves were granted one day of the week to worship God, play music, dance and sing in praise of the Lord. These religious manifestations were a way to manifest identity and awareness. They were also the origin of black leaders. The preachers were the logical leaders of black communities after the Civil War. Black preachers ran for office, were elected and became congressional lawmakers. It is no surprise that in the 20th century the first black candidate to run for presidential office – albeit not entirely successfully, because he was not elected – was Jesse Jackson, a preacher. In the early 20th century, Adam Clayton Powell Jr. was the US’s most powerful black Congressman. He was a preacher from Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church. Dr. King himself was also a preacher. His identity as a black Christian, his role as the organizer of a church as an institution that preached resistance to racism, to racial pressure, created a tradition that is generally progressive and hopeful with regard to challenging inequality and government repression. Therefore, this resulted in a powerful progressive tradition, which is offset by the conservative tradition of the Pentecostal churches.

Are your theories and work challenged to any extent at Columbia University?

I don’t know of any people who challenge me. I am not worried about criticism; I worry about doing the work I have to do. We are focusing on intellectual projects, on Malcolm’s life, and on a project called “African and criminal justice.” If you search our website for the words “race, crime and Justice,” you will see that we organize a course for young blacks and Hispanics at Rikers Island, the biggest prison in the United States, located on the East River. We use hip-hop and spoken poetry to make 15, 16 and 17-year olds write about their experiences in jail and about the role of the prison complex in the destruction of their lives and that of their families. We promote voter organization and education by giving them information [voter education includes information on how the voting process works, how votes are counted, how to use the voting forms, how to register for voting to get a voting card, etc.]. I teach classes on a regular basis at Sing Sing, another New York prison. I’m not worried if people dislike the work I do.

You define yourself as a Marxist. I imagine that, as a black Marxist professor at Columbia University, studying such a controversial person as Malcolm X is far from being a comfortable position, right?

But you must keep in mind that Edward Said was here for many years. And he was on the national board of the Palestinian Liberation Organization for many years. His book on oriental studies led to the creation of a field of knowledge known in the United States as cultural studies. And one hundred years ago, Joel Spingarn was a professor here [professor of comparative literature at Columbia University from 1899 to 1911, a Jewish civil rights activist who strongly encouraged, back in the 1920’s, the publication of books by black writers]. Therefore?

What is your feeling about the future of blacks here in the United States? Is it possible to achieve a situation of real equality, to effectively end all racism, to achieve real democracy in this sense? Do you believe this will ever happen?

I believe that our situation in the United States is complicated because of what my texts refer to as color-blind racism. This means that the signs that used to mean black and white during the Jim Crow era were eliminated. [Marable is referring to the Jim Crow laws, segregationist laws in effect from 1876 to 1965 in the Southern states; these laws decreed that public schools and most public facilities, including trains and buses, had to have segregated facilities for blacks and whites. Officially, these laws were revoked by the Civil Rights Law of 1964]. Laws were approved establishing the right to vote, the access to jobs without any racial discrimination. Affirmative action laws were approved (for a brief period of time, but these laws are now being dismantled). However, despite political regime changes, the reality of racial inequality still affects millions of blacks. How can this be? Well, under what I refer to as color-blind racism, there are three basic institutions that reinforce the racial discrimination process: mass unemployment, mass incarceration in prisons and massive loss of voting rights. Each one of these elements reinforces the others. In Harlem, real unemployment rates for adult black men range from forty to fifty percent, including the under-employed, in other words, men who only find part time jobs. Mass unemployment affects the rights of prisoners: in 1980 there were half a million Americans in jail; this figure has now risen to 2.3 million. But this underestimates the actual number. The real number is six million, if we include those who are doing time in jail, those who are on parole, and those who are under observation; half of this number consists of blacks and one fourth consists of Hispanics. All of these people lose their voting rights. In the 2000 presidential election, 800 thousand residents of Florida were unable to vote because they had criminal convictions – 40% of these were black. George Bush was elected by less than 550 votes. Eight hundred thousand voters couldn’t vote. Eight hundred thousand! They’re American citizens, they pay taxes and they will never be able to vote again. In the state of Mississippi, one third of all black men lost their voting rights; they will never be allowed to vote again because they were convicted of one crime. Therefore, if you break the law when you’re 18, do your time and leave jail at the age of 21, you will not be able to vote even when you’re 70 years old. Is this a democracy? How can this be justified? Thus, the loss of voting rights and mass incarceration result in the exclusion of the poor, the unemployed, ethnic minorities, blacks, mulattoes, and Hispanics from the country’s political institutions. Democracy in the United States is undergoing a major crisis under an increasingly authoritarian and repressive government that allows law enforcement officials to resort to violence and extreme force. A few days ago (early December 2006) a car with three young, unarmed blacks, was hit 50 times by police bullets. The youngsters were unarmed. This kind of routine violence happens in cities all over the United States.

So what should be done to increase the participation of blacks in the political process?

I’ve thought and read about this a lot. The most critical issue we need to address is the political effort to transform repressive voting laws, to restore the right to vote to six million Americans, most of whom are poor, working-class blacks or mulattoes, whose citizenship rights and voting rights were taken away. This has become increasingly important.

What is your opinion on the compulsory vote, as in Brazil?

I would prefer that election day be scheduled on a Saturday and Sunday, on a weekend, so that more people could vote. I’m not against compulsory voting, but the dominating class in the United States would be horrified by this idea. They don’t want people to vote, they want the ideology of the oligarchy to control the political scenario.

So changes will entail many years of hard work…

Yes. But I believe that many leaders will come from the more oppressed segments of society. I think leaders will emerge from among the young, women, the many poor people, the prisoners. This is part of the reason why I do educational work at prisons, because, just like Malcolm X, I believe that the most depressed views can offer individual men and women a broader social view.

I would also like to ask you how your project on Malcolm X, your academic research, can influence political activism in this sense. Because it seems to me that your project is not only a research project – it is also focused on action. What is the link between your research project and your political views in this case?

Malcolm X provides the structure for a radical and independent policy and for the rise and development of leaders focused on the challenges of power and of the white institutions in the United States. In Living Black History, I documented how and why Malcolm’s vision was so important, and not only for historical reasons. Of course I would like to conclude the biography within the next couple of years and move on to another project, but I believe that Malcolm X stands for a model. I’m not suggesting that Malcolm was perfect, far from this. He made many mistakes, like all political leaders do, but we can learn a lot from his example, his courage and his social views, and from the vitality of his vision. We can learn a lot about the capacity to resist Abu Ghraib, the war in Iraq, examples such as the Katrina… the black corpses floating in the Mississippi River… We learned to analyze and to understand the real meaning of government in action, because the blacks were the victims and were simply left to die; the whole world witnessed this, the whole world witnessed the crime committed by the government under Bush.