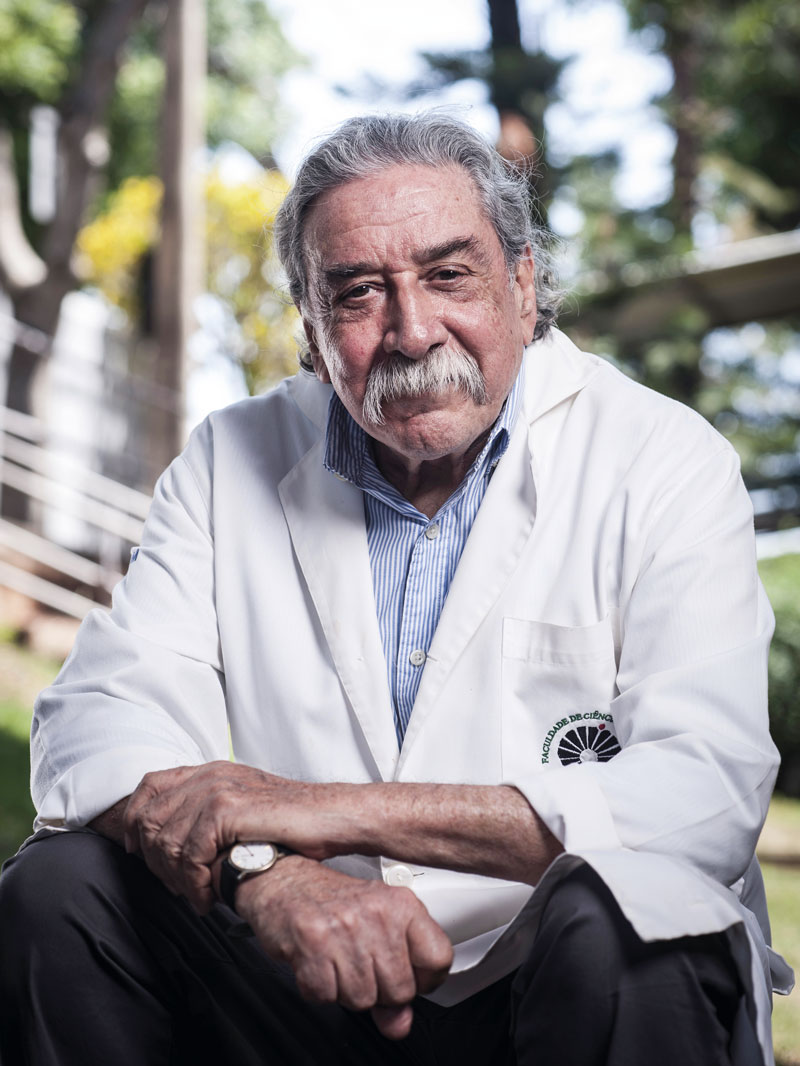

Léo Ramos Chaves/Pesquisa FAPESPEvery morning, Argentine physician Luis Guillermo Bahamondes arrives early at the Reproductive Health Research Center of Campinas (CEMICAMP), created in 1977 to boost studies in the field of women’s health at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP). Retired since 2016 from the university, where he recently received the title of professor emeritus, Bahamondes does not stop. “I work every day,” he says.

Léo Ramos Chaves/Pesquisa FAPESPEvery morning, Argentine physician Luis Guillermo Bahamondes arrives early at the Reproductive Health Research Center of Campinas (CEMICAMP), created in 1977 to boost studies in the field of women’s health at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP). Retired since 2016 from the university, where he recently received the title of professor emeritus, Bahamondes does not stop. “I work every day,” he says.

In an office on the second floor of CEMICAMP, which he has presided over since 2016, he guides master’s and PhD students from the university’s Obstetrics and Gynecology Department. He also coordinates research at the center, which acts as the Latin American hub for the World Health Organization (WHO) training program in sexual and reproductive health for young professionals from Latin American and Portuguese-speaking African countries.

Born into a humble family from Córdoba, Bahamondes wanted to become a psychologist. On his father’s advice, he chose medicine, a passport out of poverty, initially to be a psychiatrist. As an undergraduate, he began an internship in a maternity hospital which reorientated his career. After graduation, he continued on to specialization in Uruguay and medical residence in Mexico, where he worked in one of the largest maternity hospitals in Latin America. “During the residency, I saw cases that I have never seen again in my life,” he says, pointing to a photo from the time.

In 1976, at the invitation of Chilean colleague Aníbal Faúndes, he went to UNICAMP, where he helped to structure teaching and research in his field and became an international reference in the study of contraceptive methods.

Married to Argentine psychologist Maria Makuch, he has three children and five grandchildren. In the interview, he talks about the importance of access to effective methods of contraception for family planning, the corporatization of medicine, and the attempts at calling the attention of policymakers to studies that impact public health.

How is women’s health in Brazil?

Women, in Brazil and worldwide, face four big issues: a lack of access to methods of contraception and care during pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum, besides a lack of care after menopause and for abnormal uterine bleeding. A lot needs to be done to meet these needs, and a lot could be saved with adjustments to public policies in women’s healthcare. We published an article in 2014 showing how much each pregnancy cost the Brazilian public sector, including prenatal examinations and consultations, the birth, and postpartum follow-up [the 40 days after birth]. It all costs US$1,000, or around R$5,000. It is very expensive. If those women who did not wish to get pregnant used an IUD [intrauterine device] or hormonal implant, long-acting contraceptive methods, the cost to the country would be less than R$1,000. For years, we have tried to influence the public policy makers. We sent every publication from our group with importance to the public sector to the health secretaries of Campinas and the state of São Paulo and to the ministry of health, with the message: “Look at this.” Do you know how many times they answered us? Not once, they didn’t even acknowledge receipt.

Are there other examples of your group’s work having an impact on public policies?

Several. Recently, a student of mine examined whether there would be a difference in the efficacy or in the occurrence of problems between the IUDs placed by physicians and those inserted by nurses, medical students, or residents [students specializing in gynecology and obstetrics]. None. The Ministry of Health tried to change the standard, to enable nurses to insert IUDs, but the Federal Council of Medicine [CFM] was against it. The ministry insisted, but, in many places, the rule that nurses cannot insert IUDs still applies. The CFM’s argument to justify the prohibition is that there is a medical act law [a legislation that defines the procedures exclusively for physicians], which prohibits nonphysicians from exploring the body’s natural cavities. The Regional Medical Council of Pernambuco decided in favor, and there, nurses can insert them.

Women face a lack of access to contraception, and to care during pregnancy and after menopause

Is the CFM’s argument justified?

It is a corporatist and meaningless view. Nurses do not have private practices; they will not compete with physicians to insert IUDs or hormonal implants. In the Basic Health Centers this would allow the physician to dedicate themselves to patients with health issues, while the nurse would see the healthy women, which are those who seek methods of contraception. Here at CEMICAMP, we insert many IUDs because we train the nurses. For years we had seven doing the procedure, some retired and now we have three. We have proven that nurses insert IUDs as well as or even better than physicians. The government has invested in placing postpartum IUDs, 10 minutes after delivery of the placenta, with the woman’s consent, preferably given prior to the birth. Look at the paradox: who attends births in the SUS [Brazilian Public Health System]?

The physicians, no?

Not only physicians. Forty percent of SUS births are attended by nurses. If they are performing births, they could insert an IUD, which is a much simpler task. If tomorrow the minister of health gives an order that nurses can start fitting IUDs and hormonal implants in the 5,000 Brazilian municipalities, it doesn’t solve the issue. You have to train the personnel, have suitable logistics, and create a referral and counter-referral system for when there are problems. The copper IUD is given out in the SUS but is rarely used, because not all medical students and residents learn how to do it, despite the residency in family medicine or gynecology and obstetrics including IUD and hormonal implant placement training. Additionally, universities linked to the Catholic church and some religious hospitals do not approve of reproductive planning and the use of contraception. Do you want to see another paradox? There are 50 million women of reproductive age in Brazil. Around 80% of Brazilian women between 15 and 49 years old use some form of modern contraception, but 55% have unplanned pregnancy. Something is wrong.

Which methods of contraception does SUS offer?

Condoms, combination pills [containing the hormones estrogen and progestogen], and monthly and three-monthly contraceptive injections, besides the copper IUD and emergency contraception, the so-called day-after pill. They are all used regularly. But there is no transdermal patch, vaginal ring, hormonal IUD, or implant.

So why are there so many cases of unplanned pregnancy?

Because women have to book a consultation in the health centers whenever they need more contraceptive pills. It would be more practical to give a three-month prescription, instead of a monthly one. Half of the women abandon using the pill after one year, because it can cause gastric discomfort, menstrual disorders, headaches, and other foreseeable issues. If women take the contraceptive pill, taking it perfectly without forgetting a single day, the failure rate is practically zero. But, 23% forget to take it on some days in the month and get pregnant. It is necessary to take it correctly, because the quantity of hormone in the pills is increasingly higher. When you forget, the probability of ovulating and consequently becoming pregnant is extremely high. That is why the pharmaceutical industry encourages taking it every day. One solution would be to use the more effective long-acting methods, such as the copper IUD, hormonal IUD, or contraceptive implant. There is no doubt that they are the best. But it is necessary to assess each case. If a woman wishes to avoid pregnancy for up to a year, the contraceptive pill, patch, or ring is the best option. If another woman already has two children and doesn’t want any more, they can use an IUD.

Are the long-acting methods widely used?

We don’t know. The last Demographic Health Survey (DHS), a national survey that includes the use of contraception, is already many years old. It showed that only 2% of women aged 15 to 49 years used long-acting contraceptives. Let’s imagine that it has risen to 5%. Copper IUDs fail in 10 out of every 1000 women, a very low rate. Subdermal implants fail in four out of every 1000, and hormonal IUDs fail in two out of every 1000, extremely low rates. We don’t have more women using them because the government refuses to put the hormonal IUD and implant on the list of SUS priority medications. A recent law determined the use of the implant in vulnerable populations, such as people living on the streets, or HIV carriers, but it was never implemented adequately, it was not distributed correctly to the health centers.

What is the main consequence of unplanned pregnancies?

Many are terminated in clandestine abortions, since abortion is illegal in Brazil. This contributes to increased maternal mortality. Around 40 years ago, there was a huge scandal in the Brazilian House of Representatives, when it was discussed if the physician should state whether the woman was pregnant or died as a result of problems during pregnancy, child birth, or postpartum. The conservatives were against it, because this information would show the real maternal mortality rate and would show the scale of avoidable maternal mortality, such as that caused by unsafe abortion. There is a lot of unplanned pregnancy in Brazil and the number of unsafe abortions is hard to estimate, because these data are not part of the official statistics.

We have proven that nurses insert IUDs as well as or even better than physicians

In 2023, the Supreme Federal Court resumed the debate about the right to abortion, but stopped. How do you see the situation?

In my opinion, churches and governments do not have the right to tell a woman what she can or cannot do, because the burden of a pregnancy, planned or otherwise, falls mainly on her. The Netherlands legalized abortion a long time ago. There, fewer abortions occur every year because women have better access to contraceptives, which results in fewer unplanned pregnancies. I also think it is necessary for women to have the right to terminate a pregnancy when the method of contraception fails, as well as in cases in which the pregnancy is a result of rape, or if there is a risk of death to the mother, or the fetus does not have conditions to survive [Brazilian legislation does not punish the last three cases]. How many women with unplanned pregnancies have abortions? Not many. In Argentina, which made abortion legal some years ago, not as many cases occur. Neither in Uruguay or in Cuba. In Colombia, it was said that when a woman went to a medical service and asked for an abortion, the process of terminating the pregnancy had already began when she discovered she was pregnant and decided that she did not wish to continue the pregnancy. Medical abortions, done with drugs that are not sold in Brazil, occur as if it is a menstruation in over 95% of the cases. For it to work, besides legislation that permits abortion, it is necessary to have access to the medications, otherwise it cripples the public policy.

Why does the burden of pregnancy fall on the woman?

The woman has to take time off work during the pregnancy. Afterwards, they have to organize a nursery for the baby, breastfeed, etc. In a recent study, the epidemiology group at the Federal University of Pelotas examined what happened when women who got pregnant in their adolescence reached 30 years of age. They achieved lower education levels and earned less than men. It’s a sensational article that every public policymaker should read. The family planning law [Law no. 9.263, of 1996] says that the government has the obligation to provide methods of contraception without cost. But having the law is not enough. It has to be implemented and Brazil has not managed that yet.

Does responsibility about prevention also fall on the women?

In theory, it should be shared by the couple. It is the woman who gets pregnant, but it should be the couple’s responsibility. There is positive shared responsibility, when men accompany and encourage the pregnancy. And there is negative shared responsibility, when the man says: “You are not going to use an IUD because the pastor says that you shouldn’t or because the wire hurts the penis.” Or when there is a side effect and he says: “You have to stop this.” Then, when the woman becomes pregnant, he says: “How did you get pregnant?” In the outpatient clinic at CEMICAMP, more and more men are accompanying women to consultations about contraception, but there are those who remain outside, waiting for the women to be attended to.

Why don’t they enter?

Because they don’t want to. We invite and encourage them to take part. They have the right to enter with the woman, but they get embarrassed. In Brazil, although violence against women is still big, there is a cultural difference from the other Latin American countries. Men do not insist that their child is male. In Mexico, Peru, Ecuador, and other Andean countries, having a boy is still considered important. When I was a doctor in Mexico, I would say: “Look, it’s a girl!” and the man would say: “Another one?!” When my daughters were born, in Mexico, I took flowers for my wife and a roommate asked: “Did you have a boy?” My wife explained that it was a girl and they couldn’t understand: “And your husband brought you flowers?” When the second was born, I also took flowers and another roommate had the same reaction.

How would you assess the training of gynecologists in Brazil?

The public universities in São Paulo train good doctors. The problem is that there has been a proliferation of mediocre quality schools, which leads to doctors with bad training. Every week there are doctors accused of misconduct towards women. In my time, they didn’t teach us that we had to respect the patient because it was implicit.

What led you to dedicate yourself to this field?

I am from a very humble family. I was born in the maternity hospital of the National University of Córdoba, where I later graduated. I was just born there. My parents soon moved to Mendoza, in search of a drier climate, because my mother had severe asthma. We lived in an adobe house, with an external toilet. In 1958, my father managed to buy an apartment with an internal toilet, heating, and even a refrigerator. But my mother died soon after and didn’t get to enjoy any of that. When I had a year and a half left to finish high school, my father started to ask me what I was going to do and told me: “Remember that a university diploma is the passport to leaving poverty.” During the vacations, he used to take me to the School of Agronomy, in Mendoza, where he was an employee. He was also an entomology enthusiast. Three insects that he discovered take his name. He would take me to look at insects under the microscope and magnifying glass, with the idea that I would study agronomy.

I think it is necessary that women have the right to interrupt a pregnancy when the method of contraception fails

It didn’t work out.

One day, I told him: “Dad, I’m going to study psychology.” He said: “If you study psychology, you won’t escape poverty.” We are talking about 1960, when not much value was given to psychology. Then, he said: “Why don’t you study medicine and dedicate yourself to psychiatry? Go and do what you want, but with a diploma valid in Argentina.” So, I went to study medicine in Córdoba, 700 kilometers from Mendoza. At the time, it was like moving to another planet. My father was unable to support me and I soon started working. I sold lottery tickets, worked in a print shop, and did lots of things until I ended up as a bus inspector for the municipal government of Córdoba. During university, I entered the Provincial Maternity Hospital as an intern. They didn’t pay me, but gave me the option of having meals every day at the hospital, which was already an immense help. I would be on duty watching the more experienced doctors attending births and performing curettage [scraping of the uterus]. When I graduated, in 1971, I went to work in a family planning clinic in Córdoba, which was part of an institution based in New York. People from the left wing said that we were right wing because we used IUDs, an act of imperialism, and those from the right wing said that we were communists, because we used IUDs. Afterwards, I went to Uruguay to further my training. Upon finishing, in 1973, I didn’t feel that I was prepared and I found a leaflet offering medical residency in the Mexican Institute of Social Security. I sent the paperwork and, when I returned to Argentina, at Christmas of 1973, I received a letter saying that I had been accepted for a three-year residency. I looked for a boss and asked what to do. He said: “Leave, while there is time, by your own means. The situation in Argentina is getting ugly and you will probably have to go against your will.”

Were you a left-wing activist?

I had taken part in the student movement and had a police record. I took part in the demonstration and was arrested once. I sold my car, bought an airline ticket, and went to Mexico. My wife, who is a psychologist, stayed in Córdoba, waiting for me to rent an apartment so she could come. But I had bad luck. On the first day of the residency, I had appendicular peritonitis, it was operated and I was hospitalized for 20 days. My colleagues called my wife and told her: “We have had to hospitalize Luis. He underwent a small surgery and it would be good if you came to Mexico.” When I left hospital, we rented an apartment. As we didn’t have money, we only bought a bed and a refrigerator. I only bought a pillow when I received my salary from the hospital. Our two eldest daughters were born in Mexico.

How was the medical residency there?

Sensational. In Brazil, the residency in gynecology and obstetrics was two years at the time. There it was three. We did pathological anatomy, endocrinology, cardiology, X-rays, oncology, and general surgery. I worked in a hospital complex with 255 gynecology and obstetrics beds and in the associated hospital, for healthy pregnancies, with 350 beds just for obstetrics. In the two hospitals, 140 babies were born each day. We worked 90-hour weeks, but I lived in front of the hospital. I saw cases in my residency that I have never again seen in my life, like open abscesses in the pericardium, and pregnancy with hepatic rupture, among other things.

What brought you to UNICAMP?

In March 1976, in the World Gynecology Congress, in Mexico, I met Anibal Faúndes, who asked: “What are you going to do when you finish the training?” I told him that I didn’t know, but that I wouldn’t go back to Argentina. He told me about an Argentine in San Antonio, in Texas, starting to research in vitro fertilization, and asked if I wanted to go there. But my wife didn’t want to educate the girls in the USA. Faúndes then invited me to come to UNICAMP, where they needed professors. I arrived unable to speak Portuguese. I had to teach the residents to operate, give classes, run an infertility clinic, and help with contraception. I was contracted to work with infertility, not with contraception. But I abandoned infertility because I soon discovered that the public sector was not willing to invest in resolving the problem of low-income women. Treatment with synthetic hormones, in vitro fertilization, and any assisted reproduction procedures are expensive. In 1982, we decided to return to Argentina, because democracy had returned. I felt that I was indebted to the country because I had graduated in medicine at a public university free of charge. But we did badly. I took part in a recruitment process at the provincial maternity hospital, from where I had left, passed, but they did not give me the position. I opened a clinic, but I didn’t have the courage to charge. I always remembered a professor from the University of Mendoza who attended my mother. When my father asked: “How much do I have to pay?” the doctor would say: “You don’t pay anything. I have patients that pay for your wife.”

Until when did you stay in Argentina?

We came back to Brazil in 1989, when CEMICAMP managed to get its first big Word Health Organization project. I came as the manager of this project, for which I had managed funding, with Faúndes. One of my tasks was to improve the department’s research capacity, helping the colleagues to publish more in international journals. It was a culture I developed, for myself too, because I started to say: “If I have a message to say, why not say it in English?”

In nearly 40 years here, what have been your most important contributions?

The greatest contributions are the studies about the extended use of long-acting methods of contraception. We were the first group to show that the most famous hormonal IUD, the Mirena, from Bayer, approved for five years, could be used for up to 10 years.

It is the woman who gets pregnant, but the responsibility of preventing the pregnancy should be shared by the couple

Bayer must not have been happy about that.

No. But Bayer did a similar study afterwards, and nowadays the device is approved for eight years in the USA. In Brazil, we are waiting for the report from ANVISA [Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency] to extend it for the same time period. The Mirena costs R$1,000 or US$200 in Brazil. In the USA, they cost US$930. Despite the price, healthcare providers prefer to pay, because it is cheaper than a birth or hysterectomy [surgical removal of the uterus]. We were also the first to show that it is possible to extend the use of a contraceptive implant with the trade name Implanon NXT, from Organon. It was approved for three years. We showed that it could be used for up to five years.

Where did the perception that it was possible to extend their use come from?

Initial studies showed that the amount of hormone at the end of the five years of Mirena and three years of Implanon surpassed the necessary levels to provide contraception.

How are the assisted fertilization techniques?

They have evolved and today they are a cake recipe. The problem is that the costs are high and a sophisticated laboratory is needed.

There is little investment in low-cost techniques. The WHO tries to do this.

You are part of a rare group of physicians that work in the university and don’t have a private practice. Why?

Because of my experience in Argentina. I felt a huge pressure from private patients day-to-day. But mainly because I have always felt that I should give society back what it gave for my graduation, despite giving it back in Brazil and not in Argentina.

At the end of September, you were at the WHO, in Geneva. What did you do there?

Because of COVID-19, it had been four years since we, the seven hubs of the Human Reproduction Program, HRP, created in 1972, had met. We spent three days reporting on our work on infertility, violence against women, maternal morbimortality or female genital mutilation, to see what was and was not working. Over the next five years, we are going to focus on supporting the Latin American centers, including Brazil, to teach them to develop research projects, contact potential financial backers, and improve the impact of publications.

Have you retired?

I don’t have a farm, nor am I fisherman, and I live with my wife. The kids have already left home. When I retired, seven years ago, we built the house in which we live, without steps. It has a bedroom with a bathroom on the ground floor and two bedrooms upstairs for when one of my daughters comes from Texas with the grandchildren. It all opens onto a big deck with a barbecue and a swimming pool. I work every day. I read, write, speak with the undergraduate students, guide the graduate students, and come to CEMICAMP, where I still have research projects. Besides the regular students, we have 13 foreign scholarship holders from Mozambique, Haiti, Guatemala, Ecuador, and Angola, who are doing master’s or PhDs in sexual and reproductive health, preferably linked to the WHO-funded projects. Three days a week, after lunch, I go to the gym. On the other four, I ride a bicycle and read a lot, mainly literature. We have a large library. Whenever I travel with my wife we come back with books. I prefer reading Latin American authors in Spanish.