Neuroscientist Luiz Eugênio Mello became the new scientific director of FAPESP on April 27—without fanfare and in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic. He is the successor of physicist and engineer Carlos Henrique de Brito Cruz, who had held the position since 2005. In addition to research and management activities at the university, Mello’s trajectory also includes working in the private sector. A professor of physiology at the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), Mello was associate dean of Undergraduate Studies there from 2005 to 2008; he also had a hand in the expansion efforts of the institution. In 2009, he spearheaded innovation activities at the mining company Vale and established the Vale Technological Institute (ITV), made up of two research units located in Minas Gerais and Pará. He recently held the position of Director of Research and Development at d’Or Institute of Research and Teaching (IDOR). A member of the Brazilian Academy of Science, Mello was also vice president of the National Association for Research and Development of Innovative Companies (ANPEI).

Mello believes that, although the pandemic falls into the “urgent” category, affecting the short term, the new coronavirus crisis makes science seem more valuable to society, as that is where answers are coming from. “We must not create false hopes and expectations for magic bullets. We have a unique opportunity to make people understand some fundamental scientific concepts and regain some prestige. The more we rely on data, scientific evidence, and the scientific method, the more successful we will be in our strategy to regain respect for science.” Over the long term, he does not foresee changes in what he deems “important” and he is clear about his goal of making the Foundation even better.

Age 62

Field of expertise

Molecular biology, neuroscience, and science and technology management

Institution

Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP)

Education

Undergraduate degree in medicine, master’s and PhD in molecular biology from UNIFESP

Publications

155 articles

He has been following, with some concern, the research-funding crisis faced by federal government agencies. In his opinion, it is causing the progressive disappearance of the system. Mello holds that collaborating with other states is very relevant to the success of São Paulo research. He argues that FAPESP should increase its national and international collaborations and widen its range of partners. “When we talk about Europe, for example, we think of the usual countries: England, Germany, France… How often do we think of Bulgaria or Romania? There is certainly a lot of quality work being done there.” In the same vein, he poses the following question: “Can I not work with states like Pará, Acre, Rio Grande do Norte?” He believes that the broader the set of regions or countries FAPESP collaborates with, the greater the potential for work and attracting talent, which benefits the areas of science and technology in São Paulo. Shortly before taking office, Mello was interviewed via video from his home in São Paulo. The transcript below shares his thoughts on innovation, his plans for FAPESP, the pandemic, and his views on science and technology.

How do you view the role of FAPESP today and what do you think could be improved in its management?

FAPESP is one of the best—if not the best—research-funding agency operating in the state of São Paulo. This is not based on opinion, but on the regularity of its funding, the stability of its processes and regulations, the significant amount of funding, its processing times, and on a series of other aspects that allow for such qualification. There is merit and concrete evidence for this. Despite these undeniable qualities, there are always aspects that can be improved. Although processing times at FAPESP are already very good today, compared to other institutions in the country and worldwide, they could still be improved. I believe important changes could be made toward simplifying processes and reducing some of what we may call bureaucracy, which might contribute to increasing efficiency. There is a very interesting saying in the private sector, which, of course, prioritizes profitability and greater economic efficiency. The saying goes: “Expenses are like nails and hair: unless they are cut, they will just keep on growing.” I would say that, in the public sector, this analogy could be applied to bureaucracy. It keeps on growing unless it gets cut. There are reasons for an increase in bureaucracy or in expenses; clearly these things don’t happen without reason. But we must counter those reasons and generate more efficiency. Gaining efficiency is an important point. In short, FAPESP is already very good, and it could improve even further. Could FAPESP become the largest research-funding agency? This is not possible, not even in Brazil. Could FAPESP become the best agency? This could be a strategic goal: having FAPESP become one of the best research-funding agencies in the world. What do we need to do to get there? We will need to study and learn more about the Foundation from the inside, so we can then plan in greater detail, act, check, and adjust.

If development agencies like FAPESP do not fund fundamental research, nobody will

How much of your planning has been affected by the current situation?

There are two issues here. One of them is usually separated into two words: urgent and important. Too often, what is urgent takes the place of what is important. Generally, what is important are long-term, structuring ideas. But these are often put aside on a daily basis due to the need to focus on the urgent. This goes for any organization and FAPESP is no exception. Of course, unless we take care of the fire first, we will end up with no house at all, and there will be no point in planning beautiful long-term architecture. I would say that the current pandemic situation does not affect the structuring principles in any way. It will impact the practical aspect of everyday life. Any action taken will please some and displease others—this is inevitable. We still need to evaluate what will be the necessary adjustments at FAPESP. They have become urgent, so we cannot avoid them. But they should not impact our long-term strategy, which is important in the goal of making the Foundation even better.

Leaving aside the crisis for a moment, what concrete strategies have you planned for your term as Scientific Director?

Let me give you some examples; a few of them have already been started by Brito [Carlos Henrique de Brito Cruz, scientific director until 4/26/2020]. Generally speaking, the process of choosing advisors is a manual one. The Subject Boards suggest names to the Deputy Board, who validate these names; the process is then sent to an external advisor for their assessment. This whole process takes time, and it wastes time. Couldn’t we do this electronically? We certainly could—in fact, the system for it is already in place. Brito began testing it with some teams and it seems to be working well. Perhaps it can be improved or enhanced; maybe there is still unnecessary human intervention in some areas. There may even be a computer that can already determine whether there is conflict of interest, assign the best advisor for a given topic considering deadlines and expertise, and automatically submit a project for analysis. We could gain efficiency, time, and possibly even quality throughout the whole process. We need to test, assess, adjust, and then—if appropriate—implement. We could make much more radical changes. We could check what the best practices are worldwide and carry out pilot studies to figure out what works and how we can improve. A large portion of the workload at FAPESP results from report assessments. Reports on scientific research, for instance. I, having myself been part of FAPESP as an advisor for scientific research beneficiaries, see enormous merit in requiring semiannual reports. Students take their accountability toward an external funding agency much more seriously than toward someone closer to them, like an advisor. This is unbelievably valuable for the system because it generates better students and reports—and, consequently, well-trained professionals. However, this evaluation system has an impact, because each semiannual scientific research report needs to be assessed by someone. It goes through the Subject Board and the Deputy Scientific Board. Maybe they do not need to go through the Deputy Board. After they are granted, the follow-up reports could be exclusively handled by the Subject Board. We will need to check whether this works or not, but it is a small example of how several steps in the internal processes can be improved in order reduce the workload. The researchers who are members of the Scientific Deputy Board are in their prime in terms of their writing, potential, and capacity. Drowning these people in bureaucratic busy work is not the best use of the brains that are available to us.

For some years now, there has been greater demand from society for investments in science to have more economic and social impact.

The dissociation between academia and society is significant worldwide. The term “ivory tower” was not coined to explain any institution of excellence in Brazil, but those abroad. The separation between academia and society has its origins in the university’s own production model. This model often implies more contemplative, long-term efforts, while in everyday life, society is more concerned with what is happening now. There is a difference in these short- and long-term perspectives. The contemplative nature of universities had an impact last April, when the Italian Mauro Ferrari resigned as director-general of the European Research Council. Ferrari wanted to do more applied research—on how to fight Covid-19, for example—while the European research community believes the agency should not focus on the short term, but on the long term. If they focus on putting out every fire that arises, nobody will do what the agency was created for. I brought up this recent event just to mention Europe, since it tends to be considered an example. Back to our situation, I understand that society in Brazil and worldwide wants to see a return on investments of public funds in university activities—quite rightly, too. Their line of thinking is: “How has this impacted my daily life?” I think this leads to several points that have to do with giving more visibility to university activities. This concern has increasingly mobilized researchers to create blogs and websites.

Biologist Átila Iamarino, a former FAPESP beneficiary, has 2.5 million subscribers on his YouTube channel, which is exclusively about science.

I do not believe that anyone in the last 10 or 20 years has given this much visibility to science. I think that in response to society’s demand for greater impact, we have several developments, including active disseminators of science like him. On the other hand, no one should be interested in killing more basic science. The issue is that it is much harder to define the merits and long-term aspects when it comes to basic science. I recently saw a cartoon about two or three people in the Stone Age using a huge amount of force to drag home a mammoth they had hunted. They were annoyed with a guy who, instead of helping, was off doing something useless. Then, in the next frame, the one that was doing something useless had just invented the wheel, although he didn’t quite know what it was for. It is difficult to define what makes sense in basic research—it is much easier to do that with academic papers that result in immediate application. If agencies like FAPESP do not fund fundamental research, nobody will.

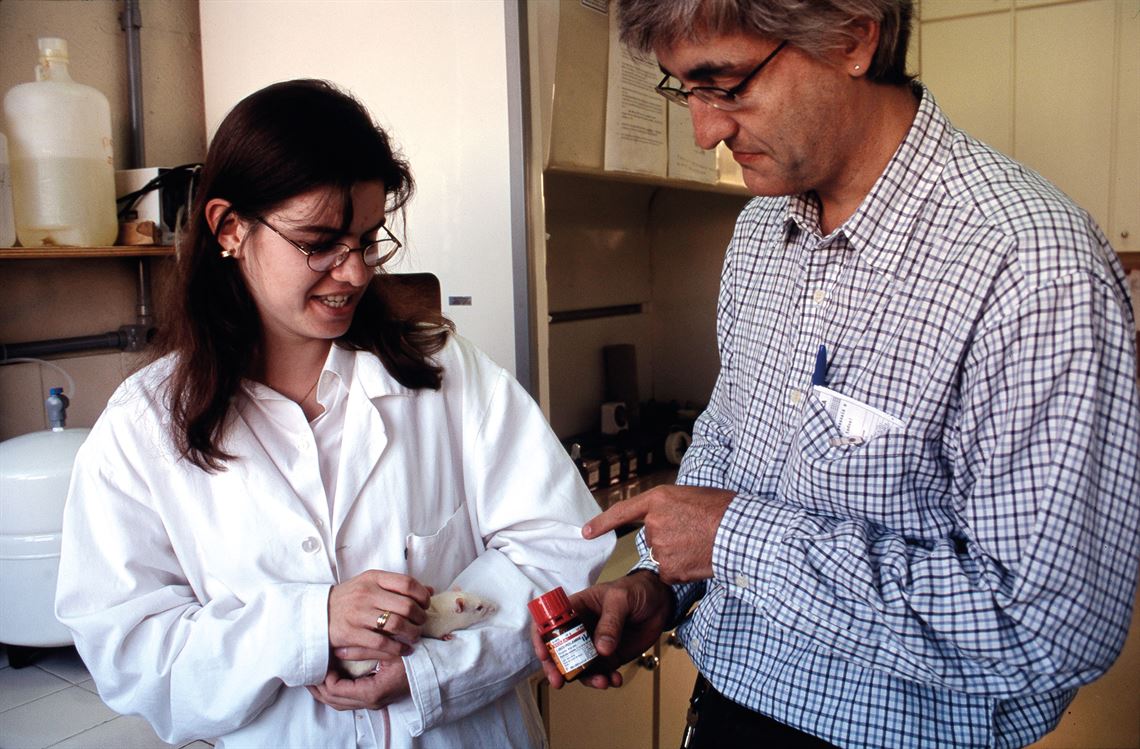

Eduardo César

With then-PhD student Simone Benassi at the Laboratory of Neurophysiology in 2000

Eduardo CésarHow has the establishment of the ITV, under your leadership, influenced your view on, and the possibilities of interaction between, the private sector and universities in Brazil?

This process was a unique experience. I had already been part of the establishment of new UNIFESP campuses. The Santos, Guarulhos, São José dos Campos, and Diadema campuses had their first entrance exam when I was associate dean of undergraduate studies. The creation process, both in science and in corporations, is captivating. It is something I truly enjoy. The process of establishing the ITV and developing the IDOR, which is the Research and Teaching Institute of the D’Or São Luiz chain, allowed for this interaction with the private sector. It is an incredible experience to seek to identify and reconcile differing views. Again, it has to do with the issues of short- and long-term planning. It seems that in a company like Vale, deadlines are always urgent: issues must be solved, and they must be solved quickly. But Vale also has long-term issues, which can only be addressed through generating knowledge. I think my experience at that company gave me a more practical sense of the world. I spent nine years at Vale. When I first joined, I was seen as a university professor, an academic, and that bothered me because in practice I wanted to be seen as just one of the company’s directors. As time went on, I was considered one of the directors. It is almost an ambassador-like role. You can speak the language of the foreign country you are in, but you are a representative of the original country you came from. The more ambassadors we can have, the better, because we can then break down the resistance on both sides. The most valuable aspect to me was gaining a more practical sense of the world, more impatient in some ways. Even while thinking about the immediate results, the company allowed itself to have a long-term initiative. I like to mention the work of a geologist who has become a great friend of mine, Roberto Dall’Agnol, a member of the Brazilian Academy of Science [ABC]. Imagine a private business that has a member of ABC as part of its research institute. It is remarkable. He had a paper titled something like this: “Palynological Assessment of the Holocene in the Western Amazon.” Upon reading such a title, one’s first thought is: “This is basic research.” After all, it was something about assessing pollen in an ancient geological era in a region of the Amazon. But the project, in addition to generating fundamental knowledge that did not exist previously, also helped accelerate an environmental licensing process for the largest mining enterprise at that time (2014), not just in the history of Vale but of the entire world. For the company, the impact of anticipating licensing by six months was hundreds of millions of dollars. This was only possible because the company had scientific data: two years of assessments of the lake in the region during the drought, during heavy rainfall periods, then during the next drought—as well as physical, chemical, and biological information both past and present. Information is essential and, without science, we have nothing. The institute carried out this work and it was a success; it featured several scientists. It is great to be able to help build integration models, which are still quite rare in Brazil. We could do much more.

Is this one of the more interesting aspects of the relationship between businesses and universities, in your opinion?

Absolutely. In practice, the number of businesses with the potential to collaborate with academia is huge. The terms of Perez [José Fernando Perez, scientific director between 1993 and 2005] and Brito [2005–2019] cover a 27-year period. During this time, FAPESP had been increasing its collaboration efforts with the private or business sector. This interaction can be optimized and approached in other ways. It’s critical to reduce prejudice and generate understanding: what does each side want from the other, so that the relationship is transparent and both sides deliver? The clearer this relationship is, the better it will be for all parties.

During the current pandemic, we have a unique opportunity to make people understand certain scientific concepts

Considering your experience at Vale, would you say that private institutions are also starting to look more toward the long term? Is there a change underway?

It is not clear to me what has already changed. But I am sure that a company needs to have certain traits in order for it to want to or be able to look toward the long term. And one of these traits is being large enough. There is a critical mass beyond which they can afford to dedicate themselves to the long run. If we look at the outside world, several companies have had the long term in mind for a while. And there are also examples involving frustration. One of them is that of Xerox, which had an incredibly famous research center called PARC, Palo Alto Research Center, where ideas for the digital screen and the mouse were defined and several other new devices were discussed. Did the company look to the long term? It did, but apparently there was a disconnect between the day-to-day business and these opportunities. Something like: “This is not going to help me make more or better photocopies.” Xerox was unable to capitalize on and leverage new business and innovation possibilities. Looking toward the long term and being able to turn it into a business opportunity also requires some intense internal work by the company. We need a large enough number of companies that are also big enough for this model to become viable. In addition, we need an organizational model that enables us to obtain the benefits of this long-term activity. Finally, there is another issue present in several papers on innovation. Xerox did not see the advantage of developing the mouse or the interactive screen, but that did not destroy the company, which remains solid. Kodak’s story was different. It was Kodak engineers who developed the system for digital photography. The issue was that this innovation would cannibalize the other services offered by the company, such as film development and sales. Kodak did not know how to properly work the opportunity it had. This is a challenge. On the business side, some insight is also required. Hindsight is 20/20. The hard part is developing and launching innovative products that are the result of research and will add value to the business.

How do you view small businesses?

Small businesses are the birthplace of these innovative solutions and new opportunities. Facebook and Google were not born large. They began small, but they became giants very quickly. Most companies do not have such a growth process, and when they do, they are often bought out by large companies. Conceptually, evidence shows that innovation tends to start in small businesses, and you need a cloud of small businesses that can do that. The issue is that not all innovation comes from research or technological advances. In the case of FAPESP, the central goal must always be related to research and technology. In practice, this technological development is a fundamental component of our activity.

You have said in the past that, while some business segments in Brazil do research and development [R&D], in others it is practically nonexistent. How can this issue be approached?

I think the phrase “necessity is the mother of invention” is both iconic and absolutely true. If a company is safe, with a captive market, it has no need to innovate and do research. Why make an investment that is both expensive and risky? In practice, the marketplace and competition are very healthy in the sense that they generate an insatiable search for process improvement, innovation, research activities, and technological research that can help make the business more sustainable. When we analyze Brazil’s strengths, we find significant segments. Nobody can deny that the agricultural sector is strong. There is a lot of technology involved. And precision agriculture is becoming more and more common, meaning there is use of geospatial coordinates, measurements of soil humidity and plant photosynthesis, etc. The sky is the limit when it comes to establishing new technologies in the industry. Brazil has great potential not only to improve its industry but also to generate technology that can grow and migrate to other places in the world. There are other segments that have grown in Brazil, such as the personal care industry, with large companies such as Natura and O Boticário, for example. These types of companies can also require a lot of research in order to keep their market leadership position, or their survival could be at risk. The central point is competition.

Alex Reipert / DCI-UNIFESP

Mello as mediator during a 2019 EMBRAPII event on innovation, at the Office of the Dean of UNIFESP

Alex Reipert / DCI-UNIFESPFor nine years, you have traveled from the Southeast to the North between ITV research centers. What have you noticed about how the different regions of Brazil do science?

Surprisingly, there is little difference. We had people from the states of São Paulo, Minas Gerais, and Rio de Janeiro going to work in the ITV branch in Belém, alongside people from the state of Pará and from various other locations. We also had people from all over the country working in Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais. There was an operating base in São Luís, Maranhão, some activities in Mozambique, Africa, and in Canada—one of the Vale research centers is located there. The differences are only there when we consider daily customs and certain stereotypes. Regarding the stereotypes, I think we managed to overcome them rather quickly. One just has to be willing. Generally speaking, people from the state of São Paulo are seen as arrogant, and the image of the São Paulo bandeirante (colonial trailblazer) is very negative, as almost like a religious leader going to preach to the people who are still deprived of the benefit of the word of God. In practice, the willingness to work and make things happen is universal, and the capacity to work together is huge. There are more significant differences in the accents than anything else. In terms of work ethic, I have indeed seen very little difference. The biggest divergences were perhaps in small details such as work shifts. Take our current situation as an example: during the coronavirus pandemic, we are all working under very different circumstances: from home. Many of us have children living with us in our current work environment. It is a new dynamic. Imagine a country where there are no domestic workers due to a different social structure. Many work from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. because they need to pick up their children from school, since they have no one to watch them. It does not mean they don’t care about their work; it means they hold a different set of values. It does not mean the work will not get done. I think everyone benefits from experiencing different cultures. After all—circling back to the idea of colonial trailblazers and intelligent life—is there no intelligent life outside of Brazil? When we talk about Europe, for example, we think of the usual countries: England, Germany, France… How often do we think of Bulgaria or Romania? The only reason we think less of them is due to a lack of contact with them, but there is certainly a lot of quality work going on there. The same logic applies to the metaphor I used. Can I not collaborate effectively with states like Pará, Acre, Rio Grande do Norte? Do all the effective collaborations take place exclusively on the South-Southeast axis? When a company has the potential to do a lot of business and attract talent in a higher number of regions or countries, its growth potential is much greater. The benefits are significant. Bringing this point back to FAPESP, I believe that the more collaborations we can achieve—not just with large organizations—the better. The more we collaborate, not only with institutions that are tier one, two, or three worldwide, but also with several others at different levels, the more beneficial this will be for the development of science and technology in our state.

This health crisis is unprecedented in recent decades. FAPESP has put out two calls for proposals—one for small businesses and another for university research groups. Can FAPESP help more?

It can. In mid-April I was a guest at my first FAPESP Board of Trustees meeting. Some board members’ very understandable concern with the aftermath has already been mentioned previously. What will happen when enough people have been infected and we face the possibility of a return to normal life? There are several issues to be faced one, two, or three months from now. The long-term concern is related to people’s mental and emotional health after this crisis. First, we need to simulate and scale this return. Should we do each neighborhood one at a time? Or by business segment? Based on permission via an app? Which company will sell this application or what type of encryption will be used? The aftermath depends less on long-term research and more on immediate applied research. Perhaps it should be more geared toward companies than the academic sector, but it is sorely needed by society. There are other research fronts as well: how did this epidemic evolve? Some countries have experienced it differently. What system did they use and how are they learning from it? There are many areas on which the Foundation can work.

During this current crisis, researchers have regained some respect for their work and expertise. Will science emerge from this crisis stronger and closer to society?

I think we must take advantage of this window of opportunity we have been given. The coronavirus is an unprecedented disgrace, but science has certainly gained the appreciation of society, as that is where answers are coming from. If drug A or B works at any given time, it is not because leader X or Y favors it. It is because there is evidence of its safety or lack thereof for certain patients. On the one hand, we must not create false hopes and expectations for magic bullets. We need to use the opportunity to build, for example, an understanding of mathematics. What does it mean to flatten the curve? What does the area under the curve mean? There are so many fundamental concepts that we can teach to society, leverage, and whose value we can make evident to people. I know a good number of people who, when learning about quadratic equations, complained that they would never use them in real life. It was as if adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing was all anyone needed to get though life. Logarithms could go straight to the trashcan. Today, these concepts could suddenly become valued. The exponential curve of the pandemic involves exponents, logarithms. We have a unique opportunity to make people understand some fundamental scientific concepts and regain some prestige. All of this is important for scientists to communicate to society. The more scientists distance themselves from mere self-promotion, including alliances with political strategies A, B, or C, and the more they rely on data, scientific evidence, and the scientific method, the more successful we will be in our strategy to regain respect for science.

Small businesses are the birthplace of innovative solutions and new opportunities

What is your view on the federal funding crisis for science? How do the hardships faced by CNPq, FINEP, BNDES, and others impact FAPESP?

The impact is enormous because it affects all collaborative activity. If during a research project I have the opportunity to collaborate with a colleague from another state, even if only regarding location issues and the transportation of samples, everything becomes much easier. Collaborative activity was and is extremely relevant to the success of our research activity. It is a huge loss for us and, for the people in these other states, it is a matter of death: the system is gradually disappearing. The reversal of this scenario depends on the country’s economy and on how investments in science, technology, and also education are structured. Investment in these three areas is long-term and should not be subject to the spending cap.

You are the first scientific director who has not come from a São Paulo state university, but from a federal institution.

I am very proud of being from UNIFESP. It is not just a personal matter. At the university, we all feel like winners.

How does this influence your view of the São Paulo science and technology system?

I think this goes back to the Revolution of 1932, which had a profound impact on the state of São Paulo, with the establishment of USP—and of my own alma mater, the São Paulo School of Medicine, in 1933. There are many developments that can, to a greater or lesser degree, be associated with that time period; even the establishment of FAPESP can be considered an outcome. If, on the one hand, the state of São Paulo has developed in such a way that it can function almost autonomously, on the other hand, any federal investments here are sort of relegated to the background. The Federal University of São Carlos [UFSCar], the ITA [Technological Institute of Aeronautics], the São Paulo School of Medicine—which then became the Federal University of São Paulo and later the Federal University of ABC—are all relevant players working toward the same larger goal. We have private institutions as well, such as Mackenzie University, PUC [Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo], Getulio Vargas Foundation. The potential for integration among these different actors is much greater than is explored today. FAPESP has a privileged position as a catalyst for integration among institutions based in the state of São Paulo. However efficient and competent the São Paulo state universities may be, there is great potential for the active collaboration of these other institutions.

One of the concerns you expressed in your interview with Folha de S.Paulo newspaper is how to make FAPESP better known. How can this be done?

We need to make people want to consider science as a possible career. Understanding what science and scientific evidence mean has become increasingly relevant in a world that is rampant with fake news. The more people have access to education in the sense of scientific thinking and the ability to look at the world and understand it, the better. For me, this is central to FAPESP. Do the students admitted into the best universities succeed because they were already great students coming in, or do they succeed because the university helped them improve? It is a hard question to answer. The point is that the science produced in the state of São Paulo will only be as great as the scientists producing it. This group of scientists will have different social and cultural backgrounds. The more diverse our science, the better it will be—almost by definition.

What is your view on the role of social sciences and humanities in the research system?

The contribution of these areas is central to any society and an inseparable and indispensable pillar of an agency like FAPESP. What makes us human involves the arts and how we interact in society. Understanding how this happens, the ethical, moral, philosophical questions of what it means to be what we are, is crucial. Art is transcendental, as are several of the fields classically associated with the humanities. Evidently, research in this field is much more difficult to qualify. But there are certainly models and standards that can possibly guide any course of action by FAPESP in this area. As much as we may be pushed an increasingly utilitarian agenda nowadays, research in the fields of the humanities and social sciences is perhaps the best example of something that is important—as opposed to the urgencies of everyday life.

Republish