Professor of comparative literature at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), poet, writer, memoirist, and essayist: Marco Americo Lucchesi, born in Rio de Janeiro, was appointed president of Brazil’s National Library Foundation (FBN) in 2023 with the mission of making the institution more transparent and accessible, in addition to modernizing its century-old collection, comprising more than 10 million items. The task includes incorporating a sensitive look at identity issues in texts written in colonial times, expanding the physical space available to store the collections, and expanding access to digitized documents.

Fluent in 22 languages, including Persian, Latin, Arabic, and Russian, Lucchesi’s first contact with literature came at an early age—as a child he would listen to his father and grandmother reciting verses by Italian poets such as Dante Alighieri (1265–1321). The history graduate has traveled the world and headed the Brazilian Academy of Letters (ABL) from 2018 to 2021. He has translated the work of authors such as Italian writers Umberto Eco (1932–2016) and Primo Levi (1919–1987), Persian poet Yalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad Rūmī (1207–1273), and Pakistani writer Muhammad Iqbal (1877–1938).

In an interview given to Pesquisa FAPESP from the top floor of the National Library in Rio de Janeiro, Lucchesi refused formalities and asked to be called Marco. Smiling and expressive, he spoke of his plans as head of the second oldest institution in Brazil and reflected on the importance of literature and history research to the process of translating authors into Portuguese.

Field of expertise

Comparative literature and translation

Institution

Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ)

Educational background

Bachelor’s degree in history from UFF (1985), master’s degree and PhD in literature from UFRJ (1989 and 1992 respectively)

Is your first language Italian or Portuguese?

My childhood was bilingual. At home, it was as if I lived in a little Italy—the language of my early years was Italian. Within my family, we didn’t speak Portuguese because it would have been artificial. I grew up on the horizons of Brazil. At school, with friends, and on the street, I always spoke Portuguese. The experience of growing up bilingual is different from learning other languages later on. Having two languages as part of my educational world was a remarkable experience.

Why did your parents immigrate to Brazil?

My parents, Elena Dati and Egidio Lucchesi, came to Brazil at the invitation of journalist and businessman Assis Chateaubriand [1892–1968]. My father was a radio and television antenna engineer. He was extremely talented in his craft: he invented different systems and won prizes. He met Chateaubriand while working as a radio operator on an Italian merchant navy boat. In the 1950s, he was invited to work on the businessman’s radio system. He was already engaged to my mother at the time, so they married by proxy. Some years later, my maternal grandmother arrived in Rio de Janeiro. They never felt like foreigners here, despite it being another world compared to their hometown of Massarosa, a small town in northern Tuscany. For them, Brazil was a land of dreams, of peace and dialogue, even with all the contradictions. I was born in Copacabana, Rio de Janeiro, in 1963. I don’t have any siblings and I don’t have any children.

Do you remember your first contact with literature?

My first contact was through music, oral experiences, and encyclopedias. My mother sang, played the piano—an instrument that later became mine—and knew many lullabies. My father loved Dante Alighieri. He could recite excerpts from the narrative poem Divine Comedy by heart. In fact, when he later developed Alzheimer’s, the only way of communicating with him was to recite half a verse of Dante and he would complete it. Dante was our link. My maternal grandmother narrated the stories of Orlando Furioso, an epic poem by Ludovico Ariosto [1474–1533]. I also remember the first time I went to a bookstore on my own and bought a book. It was in 1972—I was eight years old. I bought Poemas [Poems], by Gonçalves Dias [1823–1864] from a bookstore in Niterói. It was a 1968 edition edited by critic Péricles Eugênio da Silva Ramos [1919–1992]. I still have it to this day and sometimes I reread the sentimental notes I made when I was eight years old. In 2023, I experienced an exciting moment related to this renowned poet. The Judicial Archive of the Maranhão State Court discovered copies of Dias’s court records, which were hitherto unknown, and donated them to the National Library. In addition to being a poet, he was also a lawyer. The library is cataloging the material and it will soon be available for research.

Were you close to writers from a young age?

I met Carlos Drummond de Andrade [1902–1987] in person at the age of 21, at the 80th birthday party of the jurist and writer Afonso Arinos de Melo Franco [1905–1990]. It was an unforgettable and emotional experience. Before that, I had been exchanging letters with Drummond. Another memorable meeting was with the Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz [1911–2006] when I was 33 years old, on a trip to Egypt in 1996. He had been injured by the extremist Islamic group the Muslim Brotherhood and was staying secluded in his home, but he agreed to let me visit. I asked him a lot of questions and we talked for hours. But there were many other meetings, before and after these.

When my father developed Alzheimer’s, the only way of communicating with him was to recite a verse of Dante

Is it true that you speak 22 languages?

Yes, it’s true, but I also have a hard time believing it. Deep down, I think it’s a psychiatric problem. Jokes aside, to this day I ask myself: why so many languages? It’s over the top—it’s almost audacious. But sensitivity to languages already existed in my family, especially in my paternal grandfather, who I never knew. He wasn’t Jewish, but his family says he was taken to the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp in Austria during World War II [1939–1945]. He was able to quickly learn German and ran away. He knew how to speak five or six languages, but I don’t know how he learned them. I also think that I was influenced by exposure to the radio, which I had since I was little and which sparked a desire to communicate with other people.

How did you learn so many languages?

I learned Spanish and English as a young child. At 12 I learned German and French, and at 14, Russian. The other languages I studied later, like Arabic, which I learned when I was 30. Arabic helped me while I was traveling to various countries, such as Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, and Morocco, each with their specific variants of the language. In the beginning, I always take classes with teachers and use standard learning methods. For complex languages like Arabic, travel also helps a lot. And as if this obsession with learning languages wasn’t enough, I invented one of my own, which I called Laputar, and I even published a grammar with bilingual text, preface, and glossary. Nowadays I don’t study as many languages as I used to and I have been focusing solely on learning Nheengatu, in addition to writing. Nheengatu, also known as Modern Tupi, is an Indigenous language that belongs to the Tupi-Guarani family.

How did you go from studying history to the field of literature?

I studied history at Fluminense Federal University [UFF] in the 1980s, when the institution was still developing its master’s and PhD programs. I was passionate about the subject and authors who wrote about chronotopy, which is the way temporal and spatial relationships are represented in artistic work. I already considered literature a fundamental space for achieving my goals, which were to write poetry, essays, novels, and memoirs. So after graduating, I chose to study comparative literature, its historical contexts, theoretical frameworks, and methodological references. I did my master’s and PhD at UFRJ and my PhD was on Dante. My thesis was published in a book titled Nove cartas sobre a Divina comédia [Nine letters about the Divine Comedy; Bazar do Tempo, 2013]. Each chapter is a different letter addressed to the reader, each reflecting on different themes and aspects of the Divine Comedy, from hell to paradise. I completed a postdoctorate at the University of Cologne, Germany, in 1994, in which I studied the philosophy of the Italian Renaissance, especially the work of the Neoplatonic scholar Marsílio Ficino [1433–1499], who was a philologist, doctor, and philosopher.

Can you tell us about your research interests?

I study the literary systems of different countries, including Italy, Iran, Turkey, Greece, and Russia. A literary system is a concept that encompasses all the elements that comprise the literary situation of a given location, such as tradition, movements, publishers, associations, and other aspects. In my research, I try to understand the relationships between history and literature and the translation processes of different authors. I have examined these interactions in various projects, such as a study on the borders between fiction and essay, history and literature, based on the work of contemporary Italian writer Claudio Magris. I also investigate the ethical dimensions of translation, through analyses of semantic and cultural changes that occur when a text is changed from the source language to the target language.

Ana Carolina Fernandes

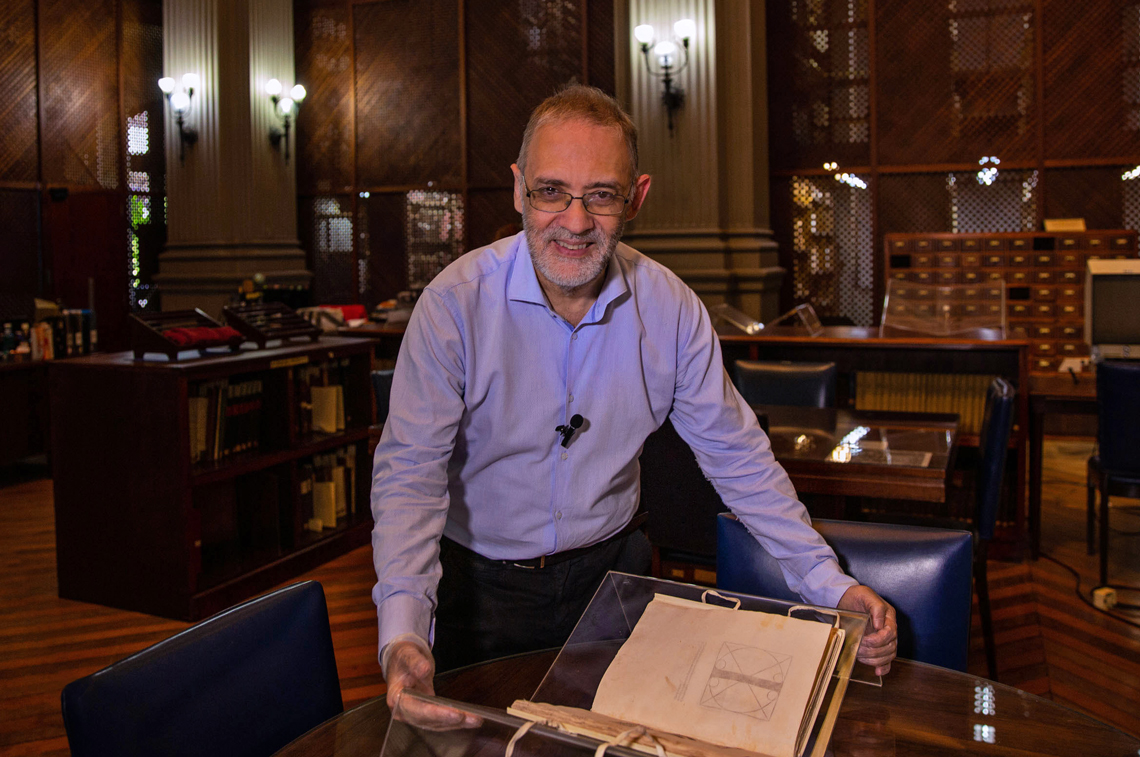

Lucchesi showing a very rare text produced by a Franciscan friar between 1445 and 1517Ana Carolina FernandesHow do your translation work and research feed into each other?

This is one of the central questions of the research I was doing, funded by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development [CNPq], before I became president of National Library. The work of a translator is artisanal in a way, word by word, but it has to be balanced with knowledge about the history and literature of the countries in question, and semantic meanings have to be adjusted according to the context. The translation process does not happen solely through relationships between languages—it requires prior knowledge of literary systems. In other words, translation is a field in which historical and literary aspects need to be combined symphonically. Theoretical knowledge has to be aligned with practical knowledge of what works in terms of rhymes and metrics. Theory and practice need to be self-correcting and to provide constant feedback. This is a major challenge, especially when it comes to translating poems. These proposals guided my translations of authors such as the Romanian poet and mathematician Dan Barbilian [1895–1961], the German poet, theologian, and physician Angelus Silesius [1624–1677], and the Russian poet Velimir Khliébnikov [1885–1922].

Why is translating poetry so challenging?

Poetry can make great leaps, uniting apparently disparate elements and merging things that seem far apart, offering a spark for understanding the meaning. Thus, from the impossibility of dialogue, the poet creates a means to break through barriers, to cross borders, and this intention needs to be present in the work of recreating each verse. The translator may feel worried or distressed by the notion that it is only possible to verge on the meanings of the original literary text, and that the task is imponderable and imprecise by nature.

What was the most difficult text you translated?

I started translating when I was 15 and I continue to this day. This year, for example, I did two demanding translations: Babel [Attar Editorial], by the contemporary Turkish poet Tozan Alkan, and Caderno azul [Blue notebook; Editora Patuá], by Yunus Emre [1238–1328], which I translated from Old Turkic. Both involved a great deal of work, since they required not only knowledge of the language, its rhymes and metrics, but also the recreation of the Turkish literary system, both ancient and modern, for the Brazilian literary system. This means I had to mobilize my knowledge of the history of both countries and theoretical references of translation philosophy.

Where does your interest in and relationship with authors from the Middle East stem from?

In my 30s, 40s, and 50s, I felt a kind of great longing for the Middle East, a feeling that stuck with me for decades. I traveled to many places, almost all Arab countries: Mauritania, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, and several others. Sometimes due to invitations to give lectures or launch books, and sometimes on vacation. In 2022, I went to Pakistan to give a lecture. I wanted to place flowers at the tomb of the poet and philosopher Muhammad Iqbal, but I couldn’t because there were rumors of a coup d’état. I had to flee the hotel at 4 a.m., making a dash for the airport escorted by security guards armed to the teeth.

Has knowing how to speak so many languages opened doors for you beyond the field of translation?

I like to use the languages I know to open spaces for dialogue. I’ll give you an example: in 1996 I was in Lebanon and I wanted to visit a refugee camp. I arrived in Sabra and Shatila and an Arab journalist greeted me in English. I promptly responded in Arabic. He was surprised and delighted, and I was thus able to visit the camp accompanied by children, elderly people, and women. It was a different experience, which showed me how dramatic life is in these places. I also participated in a group that lobbied Brazil’s National Council of Justice in defense of the right to read in prisons. Before the pandemic, I used to visit prisons to teach at the schools that operate there. In one of them, I started talking to a man who spoke Portuguese in a way that was difficult to understand. I asked him where he was from, but he didn’t respond. It was actually an inappropriate question, as it seemed to make him feel even more excluded: he was imprisoned, and on top of that, he was a foreigner. To try to alleviate the situation, I told him that my origins were Italian and he eventually responded that he was from Brasov, Romania. So I said in Romanian: “Brasov, Romania? But how can that be, my friend?” He was surprised that I spoke his mother tongue. At the end of our conversation, he hugged me and kissed me on the face.

Why speak so many languages? It’s over the top. Sensitivity to languages already existed in my family

Based on your experience in different nations and social situations, what advice would you give young researchers wishing to enter academic life?

One of the most important things is to avoid the temptation to pursue a career just out of vanity or for the stability provided by public service. Young people need be wary of this siren song. Big metaphysical questions need to be in the foreground at all times. The second fundamental point is the ability to make diverse and global interpretations without prejudice, in a methodical fashion, without rushing. Keep an open, broad outlook and avoid fads. Be careful with mechanical ideologies, anachronisms, and historicist illusions, and make sure to look at the past without confinement. We need to distrust the present and face the challenges of the future. And do not, under any circumstances, allow the institution to destroy or compromise our subjectivity. This is a constant, perennial struggle of self-regulation and refinement. The big insights relate to the structure of scientific revolutions that occur in the collective, in clashes and dialogue, but the solid core of subjectivity must govern all research and academic interests.

Shall we talk about the National Library? Can you tell us exactly what the institution is?

The National Library is a great feat, a waking dream, a box of treasures, a time machine, and bastion of infinity. To give you an objective definition, a national library is a library that, by law, serves as an archive for everything published in the country, be it books, magazines, newspapers, or sheet music. Brazil’s receives up to 80,000 to 100,000 books per year and has to catalog and preserve all of it. During the holidays, we receive 7,000 visitors per day. Our website is expected to exceed 100 million hits this year. We also work in partnership with libraries across Latin America through the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. Brazil’s National Library is globally recognized for its preservation and conservation work, and we provide assistance to institutions in Bolivia, Ecuador, Uruguay, and Paraguay. We seek to develop collaborations with others on this continent who have a lot to give to the world. We also just held our first meeting with national libraries from Portuguese-speaking African countries.

What secrets does the National Library hide? Are there any closed boxes that have never been opened?

No. What certainly must exist are surprises related to classification, meaning objects that were cataloged wrongly. In 2011, an unknown edition of the book Cosmic Harmony [1596], by the German astronomer and mathematician Johannes Kepler [1571–1630], was found. When I heard the news, I fell to my knees. In the 1950s, nineteenth-century reports by Machado de Assis [1839–1908] for the Dramatic Conservatory were found in which the writer assessed whether or not certain plays should be performed. In other words, many surprises can be unearthed by the work of researchers and librarians.

Do you remember the first time you went to the National Library?

It must have been when I was 14 or 15. I have always been enchanted by this institution. There are so many treasures. Some Egyptologists recently visited and were very impressed by the photos that Dom Pedro II brought from Egypt. We have the largest collection of incunabula—books printed in the fifteenth century, before the Gutenberg press—South of the Equator. We have the Bible of Mainz, printed in 1462, as well as works by Candido Portinari [1903–1962], etchings by Francisco Goya [1746–1828], and a music collection that is considered the most important in Latin America. One of the library’s greatest jewels is Divina proportione, a very rare book produced by the Franciscan friar and mathematician Luca Bartolomeo de Pacioli [1445–1517]. The book describes the divine proportion [also known as the golden ratio] from a Platonic perspective, arguing that mathematics and geometry are the true languages of the Universe. The book was illustrated by Leonardo da Vinci [1452–1519], who was Pacioli’s student. It was found damaged and spoiled. Some of the book was crumbling away, but the National Library’s preservation team managed to recover it as part of a project to reconstruct rare books. I have immense respect for the employees of this institution.

The translator needs to deal with the notion that it is only possible to verge on the meaning of the original literary text

What are the challenges for a century-old institution looking to modernize while also preserving the past?

Every generation opens the window of their own time and harvests the best fruits. They all complement and review a collection development policy. The challenge of our time is to expand bibliodiversity. In partnership with Indigenous leaders, we are going to rethink a collection of photographs taken by various professionals in a Yanomami village near São Gabriel da Cachoeira [Amazonas]. This year we launched the Akuli Award as a way of recognizing ancestral songs and oral narratives from traditional, quilombola, and riverside peoples, as part of our annual literary awards. I had the idea for the award while visiting quilombola villages and communities around the country. I saw that new generations wish to rebuild the social fabric based on oral narratives and songs. The Akuli Award was a first step in our efforts to expand the National Library’s ethnic inventory, without compromising its other riches. We are all-inclusive. The library is an institution that does not censor, it is democratic and stores an enormous plurality of books and voices.

The National Library has faced problems related to poor structural maintenance, which has caused water leaks, refrigeration system failures, and an increased fire risk. Are these issues being resolved?

Ten years ago, the institution began work on modernizing its refrigeration system, and in 2017 the facade was renovated. Over the past five years, money has been invested in fire safety improvements, including investments in architecture and employee training. There are still problems relating to a lack of space and the reduced number of staff. The library is continuously growing and the physical space needs to keep up with this progress. This year we received R$23 million from the federal government and R$18 million from the Diffuse Rights Fund to begin renovations of the library’s annex in Porto Maravilha, in central Rio de Janeiro. Based on these and other investments, the idea is for the annex to function as a twenty-first-century library. Funding is being increased in an attempt to improve these problems, but we have to take a cautious approach, be transparent in our spending, and respond to regulatory agencies. As a result, many projects are not put into practice as quickly as we might like.

What is a twenty-first-century library?

It is an institution without walls—transparent and accessible. We are making efforts to digitize more of the collection. Our database currently gets eight million hits per month and we want to increase the number of digitized documents so that researchers from all over the world can consult them. There must be no confusion: digital is not the enemy of analog, as many people thought in the 1990s. It doubles the preservation work and means we need to maintain two forms of heritage, in terms of their organization, but we must expand access to information. We must ensure that the National Library is not just a repository, but a great crossroads of knowledge. Finally, we face the challenge of performing more research so that we can deepen our understanding of the items in our collection that have yet to be studied in depth, including the comics repository, one of the largest in the world.