At a depth of 600 meters, during a 2017 scientific expedition near the Alcatrazes archipelago off the coast of São Paulo, a gelatinous organism surprised researchers by colliding with a submersible vehicle and emitting a flash of green light, which is an unusual phenomenon among bioluminescent animals. Nearly a decade later, a set of natural green photoproteins discovered in the marine organism Velamen parallelum was finally described. The finding, published in April in The FEBS Journal, paves the way for advances in the biomedical and biotechnological fields.

“The discovery of the chemical mechanism was purely by chance,” says biologist Douglas Soares, from the Araraquara campus of São Paulo State University (UNESP), the article’s lead author. At the time, he was a postdoctoral researcher at the University of São Paulo’s Institute of Chemistry (IQ-USP). “My project was with fungi, but out of curiosity, I opened the –80 °C freezer in the laboratory and look what happened.” Among the stored tubes, he found a sample of the organism collected years earlier and decided to analyze it.

Using molecular biology methods, cloning, and gene expression in bacterial systems, Soares discovered a set of calcium-sensitive bioluminescent proteins (photoproteins) called velamins, capable of naturally emitting green light. This characteristic is unprecedented among proteins of this type, which usually emit blue light. To study them, the biologist extracted RNA from the organism and converted it into complementary DNA (cDNA), which he inserted into bacteria to produce the proteins in the laboratory.

After purification, the proteins were activated with coelenterazine, a molecule that acts as a kind of fuel for bioluminescence, and tested for their sensitivity to calcium ions, confirming that they were photoproteins regulated by this element. “The reaction we provoked releases energy in the form of light, not heat; having a system that naturally emits green light is rare and very advantageous for in vivo studies,” explains chemist Cassius Stevani, from IQ-USP, one of the article’s coauthors.

The scientists also analyzed the spectrum of the emitted light and tested the proteins’ stability at different temperatures. As a result, they identified three main types, called alpha, beta, and gamma, the latter standing out for its greater resistance to heat and for emitting light at a longer wavelength. This increases the likelihood that this type of molecule can pass through biological tissues without being absorbed by pigments in hemoglobin, potentially allowing physiological processes to be visualized in real time.

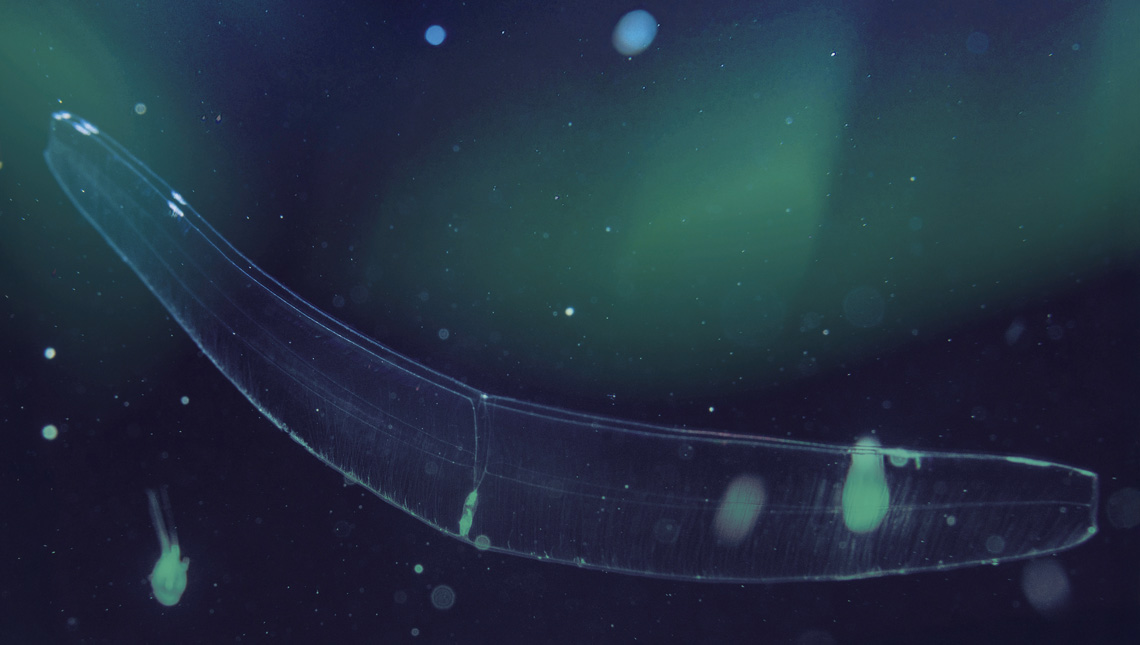

Lucy Smiechura Floating near the seafloor, the Belt of Venus is almost invisibleLucy Smiechura

For molecular biologist and biochemist Vadim Viviani, from the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar) and former president of the International Society for Bioluminescence and Chemiluminescence (ISBC), this characteristic makes velamins potentially promising for biomedical applications once modified. “Understanding how these proteins work may allow structural adjustments so that they emit light increasingly in the red spectrum, which would significantly expand their usefulness in animal models and, in the future, in clinical diagnostics,” says Viviani, who did not participate in the published study.

Only two individuals of Velamen parallelum, also known as the Belt of Venus, were collected for the study. The organism is a ctenophore, distinct from jellyfish (cnidarians), and is notable for emitting light in brief flashes when stimulated by physical contact. Because it inhabits deep-sea environments and has an extremely gelatinous body that easily disintegrates when touched, collecting it represented a technical challenge.

The opportunity to capture it arose during an expedition organized by OceanX, a private initiative focused on ocean exploration and research that employs vessels equipped with state-of-the-art technology. At the company’s invitation, Brazilian researchers mapped the country’s coastline, including chemist Anderson Oliveira, then a researcher at USP’s Oceanographic Institute (IO) and one of the authors of the article in The FEBS Journal. “The submersible was like an acrylic sphere, where we spent about 10 hours on the seafloor. When the organism struck the acrylic and emitted a green light, we used the robotic arm’s vacuum device to collect it, stored it in a bottle with seawater, and froze it.”

Oliveira is now a professor at Yeshiva University in the United States and continues to collaborate with the Brazilian team on new stages of the research. One of these projects, led by Soares at the Araraquara campus of UNESP, aims to extend the wavelength of light emission into the red spectrum and increase the thermal stability of the proteins, making them more efficient for in vivo applications.

The group is also exploring the use of these photoproteins as molecular probes for detecting calcium in environments with high ionic concentrations, such as inside red blood cells. Under these conditions, traditional fluorescent sensors, which depend on external light to function, tend to lose sensitivity because they operate at the detection limit and cannot register small variations in calcium concentration. One strategy under development is the combined use of photoproteins with different light emission wavelengths (blue and green, for example) to create dual identification systems.

Anderson Oliveira / Yeshiva University Inside this submersible vehicle, researchers observed a glow when the organism collided with the acrylicAnderson Oliveira / Yeshiva University

This approach would allow simultaneous, real-time monitoring of cellular regions with different calcium levels, offering a more precise view of complex physiological processes such as the mechanisms by which cells communicate and coordinate their functions, and ionic homeostasis, which is the balance of ion concentrations essential for cellular activity. Such advances could improve the diagnosis of diseases related to calcium metabolism and support research on cardiac, neurological, and muscular disorders.

Viviani highlights that this was the first cloning of a marine organism photoprotein carried out in Brazil, opening new perspectives for research on bioluminescence applied to local marine species. He also notes that although Brazil is renowned for its rich diversity of terrestrial bioluminescent organisms, such as beetles and fungi, its marine biodiversity in this field remains largely unexplored.

Portuguese marine biologist José Paitio, a postdoctoral researcher at IO-USP, has also expanded knowledge of bioluminescence in marine organisms. In partnership with researchers from Japanese institutions, his group described for the first time the structure and function of the biological mechanism of photophores in fish of the genus Neoscopelus, inhabitants of the depths of the Pacific Ocean. The findings were published in the Journal of Fish Biology in April and in Zoomorphology in June.

Photophores are specialized light-emitting organs composed of photogenic cells, internal reflectors, pigment filters, and modified scales. Together, these components not only enable fish to produce bioluminescence through chemical stimulation, but also regulate the direction, intensity, and spectrum of the emitted light, which are crucial factors for camouflage by counter-illumination, a strategy that makes them virtually invisible when viewed from below.

“In these fish, we discovered that photogenic cells are controlled by nerves. And, as impressive as it may seem, each photophore is connected to specific nerves, which the fish can control individually,” Paitio explains. This allows the animal to adjust light emission according to depth—a sophisticated mechanism of ecological adaptation.

Chih-Wei ChenFish of the Myctophidae family live in deep waters and can emit lightChih-Wei Chen

For Stevani, from IQ-USP, who did not participate in the study, the results are significant because they provide unprecedented information about photophores and are based on a robust sample—28 individuals across the two studies—something difficult to obtain in this type of research. He also believes the work opens the door for similar investigations in other deep-sea species. “There is another interesting fish, Malacosteus niger, with two photophores near the eyes that emit different colors of light. We want to study it because nothing is yet known about this mechanism.”

The sample used in the study by Paitio and colleagues was obtained through a partnership with the Japanese Ministry of Fisheries, as well as the purchase of specimens directly from fishermen on the coast of Shizuoka, a province in central Japan. The collected material provided sufficient volume and quality for the morphological and functional analyses required for the research.

The researchers combined laboratory techniques such as cryogenic sectioning and chemical staining, which allowed them to locate the nerves connected to the light-emitting organs, with electron microscopy to analyze the detailed structure of the pigment and reflective cells.

Another technique employed was microspectrometry, adapted in the laboratory by Paitio himself, which made it possible to measure, on a micrometric scale, the spectrum of light transmitted and absorbed by each component of the photophores. “We adapted a spectrometer to a conventional microscope and, with this setup, we were able to analyze areas as small as 40 micrometers and identify what happens to the light at that point: which part is transmitted, which is absorbed, and which is reflected. This was fundamental to understanding how the pigmented filter and the internal reflector work,” he explains.

Currently, the researcher is investigating the genetic and evolutionary aspects of these light-emitting systems, focusing on comparisons between species with different light camouflage strategies. The aim is to trace the origin of structures such as pigment filters and reflectors, determining whether they arose independently in different lineages or derive from a common ancestor. It is hoped that these studies will help reconstruct the evolutionary history of bioluminescence in deep marine environments and reveal adaptive patterns that remain poorly understood in deep-sea fauna.

The story above was published with the title “Underwater illumination” in issue 354 of August/2025.

Projects

1. Bioluminescence in fungi, centipedes, and marine organisms: Chemical and biological aspects (n° 19/12605-0); Grant Mechanism Postdoctoral Fellowship; Supervisor Cassius Vinicius Stevani (USP); Beneficiary Douglas Moraes Mendel Soares; Investment R$618,352.67.

2. Evolution and biological function of fluorescent filters in dragonfish photophores (Teleostei: Stomiiformes) (n° 22/01463-3); Grant Mechanism Postdoctoral Fellowship; Supervisor Marcelo Roberto Souto de Melo (USP); Beneficiary José Rui Lima Paitio; Investment R$445,348.39.

3. Novel luciferases and photoproteins in marine annelids (Annelida) and coelenterazine-dependent bioluminescent systems (n° 20/07600-7); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Anderson Garbuglio de Oliveira (USP); Investment R$99,676.64.

Scientific articles

SOARES, D. M. M. et al. Velamins: Green-light-emitting calcium-regulated photoproteins isolated from the ctenophore Velamen parallelum. The FEBS Journal. Online. Apr. 18, 2025.

PAITIO, J. et al. The filter in photophores of the deep-sea fish Neoscopelus (Neoscopelidae: Myctophiformes) and its role in counterillumination spectra. Journal of Fish Biology. Apr. 8, 2025.

PAITIO, J. et al. The structure of scale lens and inner reflector in the photophore of the deep-sea fish Neoscopelus microchir (Myctophiformes: Neoscopelidae): Insights into the light projection mechanisms for counterillumination. Zoomorphology. Vol. 144, 43. June 12, 2025.