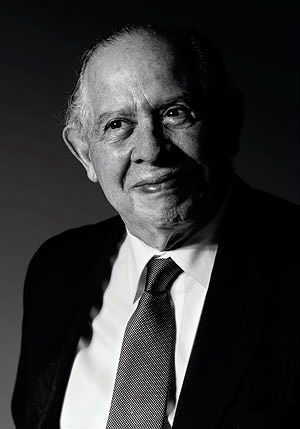

Léo RamosSeven years ago, physiologist Mauricio da Rocha e Silva exchanged the laboratory for writing. On the eve of retiring from the University of São Paulo (USP) in 2004, he decided that it was time to change arenas and face up to new problems worth fighting. He accepted the challenge presented to him by the School of Medicine to recreate the house journal in such a way as to transform it into a visible scientific publication. In addition to the necessary reforms to make it the ‘object of desire’ of researchers from the medical area, the most important thing was to significantly increase the publication’s impact factor (IF). The IF is a measure created to estimate the influence a periodical has in a given area. It represents the average number of times an article from that publication is cited by other works within a certain period.

Léo RamosSeven years ago, physiologist Mauricio da Rocha e Silva exchanged the laboratory for writing. On the eve of retiring from the University of São Paulo (USP) in 2004, he decided that it was time to change arenas and face up to new problems worth fighting. He accepted the challenge presented to him by the School of Medicine to recreate the house journal in such a way as to transform it into a visible scientific publication. In addition to the necessary reforms to make it the ‘object of desire’ of researchers from the medical area, the most important thing was to significantly increase the publication’s impact factor (IF). The IF is a measure created to estimate the influence a periodical has in a given area. It represents the average number of times an article from that publication is cited by other works within a certain period.

So far, Rocha e Silva has been successful. The IF of the journal, Clinics, has risen from 0.35 to 1.54 under his management and he expects it to exceed 2 by 2013. At the same time, Rocha e Silva has taken over defending Brazilian scientific journals against the criteria used by the Qualis periodical evaluation system from the Coordinating Office for Training Personnel with a Higher Education (Capes), which he thinks is unfair. This is not a gratuitous fight. He believes that any country that wishes to have top quality science must have publications that welcome and reflect this science with judicious and balanced support being given by government bodies.

Rocha e Silva is the son of Maurício Oscar da Rocha e Silva (the discoverer in the 40’s of bradykinin, a compound that gave rise to a line of medication against high blood pressure), who had a decisive influence on him. He frequently refers to his father by his first name, which also reflects his admiration and respect for him as a professional. The son’s scientific contributions included studies on the hormone vasopressin, and hypertonic, a solution of super-concentrated salt and water capable of re-establishing the blood circulation in people who are suffering from serious hemorrhage. Below are the main extracts from the interview.

You are transforming Clinics, a journal that was invisible for decades, into a publication of impact. How did this happen?

Clinics originated in 2005 from a previous publication, Revista do Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo [Journal of the Clinicas Hospital of the School of Medicine of the University of São Paulo], which was known as the “HC Journal” and had been important when it was created in 1946, two years after the hospital was founded. For five years in the 90’s it had no citations. This means that not even the authors themselves cited the articles they published in it. In 1998, they invited me to take over the periodical, but I didn’t accept. The Science Electronic Library On-Line [SciELO] and PubMed were just getting off the ground and it was only six years before I retired.

Why was this journal important?

It used to carry reports of complex cases studied at HC, but it was losing importance and it became a journal of original research. At the time, it was facing a problem that was common to almost all Brazilian journals of the last century: invisibility. Furthermore, the Brazilian scientific community adopted the very radical stance of wanting to publish articles in Portuguese, arguing that it was important to defend the mother tongue. This was at a time in the 80’s when French and German journals were publishing in English and even changing their names. The reason has been known for a long time: the language of science is English. In Brazil, the only journal that began in English is the Brazilian Journal of Medical Biological Research, edited in Ribeirão Preto by Lewis Joel Greene, an American who has become a naturalized Brazilian. It was the first periodical in the health area to acquire international quality.

Memórias [Memories] from the Oswaldo Cruz Institute, from 1909, was bilingual at the outset, published in Portuguese and German.

That one began well and then had a phase just in Portuguese, in which it presented only work from Fiocruz. It suffered doubly: it was in Portuguese and endogenous. In the 80’s, they began to publish it in English. Today it’s Brazil’s best scientific journal. It’s helped by the fact that they have an excellent theme, because, after all, the Oswaldo Cruz Institute is a world pioneer in tropical, exotic medicine. They take good advantage of the niche; they publish good science. It’s the only Brazilian journal whose impact has already exceeded 2.

Who took over the HC Journal?

Pedro Puech-Leão, a professor of vascular surgery from here. He performed magic: the journal started being published in English, it gained serious peer reviews and went looking for good articles. It started out from absolute zero. When I took over the journal, the calculated impact factor was 0.35. That’s a bigger miracle than going from 0.35 to 1. Being at zero means that no one wants to publish in it.

And why did you take over the journal in 2004?

That year Pedro decided to leave and the decision-making board of the HC once again offered me the publication. I went to lunch with him and he said to me, “They really want to create a decent journal, so you accept, but ask for the whole outfit, everything you need to work with, and they’re going to give it to you.” Another detail led me to accept. In the 90’s, I was on the editorial board of an American journal, Circulatory Shock. As it was not financially sound, its owners decided to ‘kill’ the journal and create a new one called Shock. As I was on the editorial committee, I was one of the founding members. A scientist came to manage it who was very good at editing. That’s when we made a blood pact. We agreed that the 30 people on the editorial body would have to send one article a year to Shock. And this article would have to be cited three or four times over the subsequent two years in other first world journals. Everybody did it. In the first year, the impact was 0.7. You have to consider that an American journal enters the ISI [Institute for Scientific Information, a service of bibliometric bases that is today part of Thomson Reuters, which is responsible for calculating the impact factor of publications] the day after it is created and this helps the impact a lot. In 15 years, it reached 3.5. I learned what factors make the difference. Some are ethical and others less so. The editor of Shock is a model of ethical behavior.

Did you use these methods at Clinics?

Precisely. When I arrived, it had that impossible name. There were 10 different ways of looking for citations. Pedro wanted to change it, but he was afraid of losing the register in PubMed [the National Library of Medicine, the gold standard of the system of periodicals in the health area]. I went to Washington to talk to the people at the National Library of Medicine. They understood. Clinics was already included in PubMed from its very first edition. I speak English well. I was educated in the US and in England, so they don´t think I’m a savage. Speaking their language well and talking to them personally makes a difference.

How did the new name come about?

Pedro wanted Clínicas. But it has an accent, so foreigners would get it wrong… I thought of Clinics, and we discovered that the name was vacant so we registered it. Only later did we discover the collateral benefits. Not having a name that announces your third world origin is good for the impact factor and for requesting articles. The Chinese know this. They no longer have the “Chinese Journal.” It’s all “International Journal.”

How much time did it take to put together this strategy for building up the journal?

We entered the ISI in 2007. It takes three years for the first impact to appear. In 2009, we hit 1.59 and we were second only to Memórias. In 2010, we dropped back a little, to 1.42, and we’re in third. The results for 2011 haven’t come out yet, but by my calculations, we’ll go back to second place. The Manguinhos journal is my model. They jumped above 2 for the first time by publishing a supplement on Chagas Disease. Everybody cites it. So I created a supplement on neuro-behavior, with review articles from Miguel Nicolelis and from an Englishman, Timothy Bliss. It was Bliss who in the 1980s discovered how neurons fix memory. He has an article with more than 5,000 citations. Our supplement came out in June 2011, but it takes six months for citations to begin. I think we’ll exceed 2.

Why is it important to have good journals here?

Brazilian science is making progress and one day is going to be top quality. If we don’t have national journals that are capable of reflecting this type of science, it’s going to go straight abroad and our authors may face not very loyal competition from foreign editors who are protecting their own group. It’s an imperative for the independence of Brazilian science to have high quality Brazilian journals, perhaps within 10 years. We need to have periodicals with impact 4.

Did you always publish in English and abroad?

When I started doing science, the first thing my father taught me was never to publish in a Brazilian journal in Portuguese if you can publish abroad. And Michel Rabinovitch, a great professor, repeated the same thing. We’re talking about 1960. No one reads Portuguese abroad, they don’t subscribe to third world journals and if we send them for free they don’t display them in their libraries. Publishing like that was tantamount to hiding your data.

Despite everything, Brazilian journals have been gaining prominence.

This is happening today because of SciELO and PubMed, which both started out at more or less the same time. The true revolution was provided by the invention of the Internet. As from 1999, you could enter PubMed’s site for free, input your keyword and carry out a search. When I graduated in 1961, I used to visit the library every week to see what had come out. This practically no longer exists. You just have to access the site of scientific publications to see what the very latest thing in the area is. SciELO originated in Brazil with the support of FAPESP at the same time as PubMed appeared in the United States. It was a brilliant idea of Rogério Meneghini’s to create a collection of journals that were seriously selected, with instantaneous open access. Brazilian articles became visible. In 10 years access went from zero to 100 million downloads a year.

Was that what raised the visibility of Brazilian journals?

Good journals, like Memórias, Brazilian Journal, Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society, passed the magic number and reached an impact factor greater than 1 in 2002. A Brazilian journal had never achieved this. Today we have 1 journal with an impact greater than 2 and 15 journals with impact greater than 1.

What are the circumstances of your struggle against the Qualis system of evaluation in Capes periodicals?

I wrote an academic study on this, which came out in December in Clinics. Capes uses the wrong system of evaluation for scientific articles. It’s not the only one; the NIHs [National Institutes of Health of the United States and other institutions] use similar criteria. I’m not the only one who thinks it’s wrong. The father of the impact factor, Eugene Garfield, has already said that using the impact factor of the journal in which the article is published and saying that the article is good is a serious theoretical error. All journals have an asymmetric distribution of citations, which means that 20% of the articles account for 50% of the citations and the lowest 20% account for just 3% of the citations. So much so that 20% of the articles in the New England Journal of Medicine, the medical journal with the highest impact factor in the world, for example, are cited very little. It’s the same for any journal. To do this work I studied 60 journals with impact ranging from 1 to 50. I found none that didn’t have this distribution. The argument of Capes and the NIH is this: if you publish in a good journal you are good. It’s not exactly like that.

How does Qualis work?

Journals are classified into eight categories; A1 and A2, B1 to B5 and C. The higher categories use an impact factor and the lower ones don’t. So if I publish in an A1 journal, I get a mark of A1. But 70% of the articles that come out in the A1 journal don’t have that good a level of citation, which comes from 30% of the articles. Because of this, 70% of the articles published there receive an upgrade which is equivalent to that of the other 30%. No Brazilian journal is A1. In the intermediary category journals, the problem is more serious because they have by obligation an upper and lower limit. Anyone who publishes an article there gets the journal’s mark, and has a 50% chance of being upgraded. I did the sums and it’s in my article. But anyone who publishes in this journal has a 20% risk of being downgraded, because their article has more citations than the average citations for that journal. If 20% account for 50% of the citations it’s obvious that amongst them there are articles with many more citations than the average for this band.

But the bigger probability is that the article will be “upgraded”?

Yes. But there’s a possibility that’s not negligible of you being downgraded because of the band system. Capes is not giving a mark to the journal. What it’s doing is giving a mark to the articles from the postgraduate areas that come out in the journals. They say this – and it’s true. It’s just that when they attribute a low classification to a journal, they’re saying to postgraduate students and their supervisors, “Don’t publish in this journal if you can publish in another with a higher impact factor.” In other words, they don’t classify the journal, but they harm it. My fight is to drive the impact factor up. If Qualis didn’t have this internal problem, in 10 years’ time we’d have a collection of great international Brazilian journals because there would be encouragement to publish. Before people think that I’m at loggerheads with Capes, I insist on saying that it’s very important. It’s the engine of Brazilian postgraduate studies and therefore of scientific production. The Capes periodicals’ portal is fantastic. The only nonsense is Qualis.

But did the Capes evaluation ever encourage researchers to publish more?

Yes. Some form of assessment of postgraduate articles is essential. The old Qualis had a serious problem: it was very slack and permissive. Everybody got top marks for their publications. They changed and created the new Qualis in 2008, which I think is more or less right for Harvard, but not for the Brazilian scientific community. They may have tightened the postgraduate belt too much, and tightened it wrongly.

Let’s talk about your scientific contributions. Did you work with your father on research into bradykinin?

Maurício is an almost impossible influence to ignore. At the beginning of my career there was also Rabinovitch, who used to encourage young researchers. My father went to USP in Ribeirão Preto when I was in the third year of medical school in São Paulo and I stayed here. One of the good reasons for this was Rabino. He was a magnet. The first destination of people who thought about doing science was Rabino’s office. At the time, Maurício gave me a problem to study: the effect of bradykinin on the kidney function. As I had learned the know–how of renal physiology I agreed. I spent four holidays, at the beginning and middle of the year, in Ribeirão studying this. Bradykinin induced secretion of the antidiuretic hormone. Here in São Paulo the person who was doing some real renal physiology was Gerhard Malnic, another great researcher. I contacted him and we began working on this. At the time, we only knew that bradykinin produced the vasopressin effect, which was antidiuresis. It’s called vasopressin because the first thing discovered is that it increases arterial pressure. Its physiological effect is to control diuresis. It’s also called the antidiuretic hormone. It’s the hormone from the pituitary gland that controls the basic volume of diuresis. In very high concentrations, it produces an effect on blood vessels. That was my important contribution to vasopressin. In my PhD thesis in 1963, I showed that bradykinin induced secretion of the antidiuretic hormone and produced antidiuresis, but this effect disappeared if we removed the pituitary gland from the animal. Later, in 1969, I proved for the first time that vasopressin didn’t just increase pressure, but that it was part of the regulation mechanism of arterial pressure. There were those who’d formulated this as a hypothesis but no one had ever carried out an experiment that proved it.

Where was it done?

Here in the School of Medicine. And it came out in the Journal of Physiology in 1969, the world’s most prestigious physiology journal. Before, during a period that I spent in London, I had managed to show the mechanism whereby bradykinin secreted the antidiuretic hormone. When I came back, I thought that this should have some physiological action. Manuela Rosenberg, a student, and I thought up an experiment to see if we could prove it. And it worked. That was my associate professor’s qualification thesis.

Did you always think about doing research?

Always. In fact, I was going to study physics. But Maurício said, “That’s nonsense, you’re going to end up being employed as a doctor.” That’s the way he was; very fascist. I went to study medicine because his influence was very strong and it worked out OK. I always say I was lucky to do what I was condemned to do because of the influence of my father. Maurício spent his life thinking that the only salvation was in science.

Did you work together?

Only during vacations. He was difficult, very demanding. At the time, we got on very well. After, we used to fight and then in the end we became friends again. His severity didn’t bother me a lot because I was prepared to work. One day I was helping him operate on a dog and my arm was up against one of those lamps with a metal shade. I said to him, “It’s burning my arm.” He said, “Do you think you’re at a health spa? Hold on to the retractor and keep quiet.” That was his style.

Did you go to England for political reasons in 1970?

I decided to leave the day they took away the political rights of 40 people during AI-5 in Brazil, of whom 25 were at USP. I went to Ribeirão to see my father, who had had an automobile accident and broken some ribs. I came back to São Paulo and went to the home of Alberto Carvalho da Silva, who was my boss in physiology and had asked for news about Maurício. When I got there he’d had his political rights taken away and been dismissed from his position as scientific director at FAPESP. That was the day I decided I was going to leave.

And why London?

I went there twice. I got a scholarship from the British Council in 1964 to do research at the National Institute for Medical Research, where there was a group working hard on vasopressin. I came back at the end of the Castello Branco government. I went back there in 1970, after the episode of the cancellation of political rights. I wrote to my English friends asking for help and got a job at the same National Institute. I stayed there for four years. When I returned I went to the Institute of Biomedical Sciences at USP. Ten years later, in 1984, I came back to the School of Medicine, where I am now.

Was this when your research on hypertonic began?

It was a little after my return. In mid-1970, Irineu Velasco, a recent graduate from Santa Casa, saw a medical error work out well : a patient submitted to dialysis received a wrongly prepared solution that was super-concentrated in salt. And this patient, who was in a bad way and in shock, came out of shock. Velasco wanted to do research on this and they suggested that he should talk to me. He came into my office and said, “I want to inject sodium chlorate [cooking salt] at 7.5% into a dog in shock [in a state of shock].” The normal concentration is 0.9%. I looked at him and I thought to myself, “Every madman comes to see me.” To get rid of him I asked him to prepare a protocol of the experiment and come back later. A week later, he brought the protocol, which was well prepared. I corrected what I thought was necessary and decided to authorize it. I thought to myself, “We’re going to kill the dog because this can’t work.” It was my luck that I told Velasco to come back because the thing worked. The curious thing is that hypertonic solution, water with 7.5% salt, takes a dog out of shock, but not a rat or a rabbit. We don’t know if it works with cats or not; no one’s ever tried. And it takes people out of shock, but it has no great advantage over the standard, state of the art treatment.

If you’d bet on the wrong animal…

It would have stopped there and then. But the dogs came out of it alive. We removed 40% of the dog’s blood. If nothing had been done, he would have died in a matter of hours. We gave him this super-concentrated solution and the next day the dog was alive. We repeated it several times and it was always the same thing. We created a new protocol to try and clarify how it worked and this became his PhD thesis. Velasco was the father of the child. I think that without my scientific experience in perfecting projects, perhaps it wouldn’t have advanced as much as it did. But the idea was his. The work lasted for many years and was supported by FAPESP.

Was the solution tested on people?

Various times. The first systematic study was carried out at HC by a doctor who’s today famous in oncology, Riad Younes. Later, two major multicentric trials were carried out in the United States, one coordinated by the University of Houston and the other by the US army in eight different hospitals. When a controlled clinical trial is undertaken, a new idea is compared with a classic idea, the state of the art. This study can end in one of three ways: success, if the new idea is better than the old one; failure, if the new idea is worse; or what is called futility, if the new idea is neither better nor worse. The two trials ended in futility; hypertonic solution is as good as the state of the art, but no better.

What’s state of the art?

Normal physiological serum, with 0.9% salt, eight times more diluted than hypertonic solution. Unfortunately, there’s a property of statistical analysis that says that testing difference is much cheaper than testing equivalence. The problem with equivalence is that the statistical test requires a very much greater number of entries to be able to state that “it’s equivalent.” That’s why a result that’s not different in a study to test difference is called “in futility.” No one ever decided to spend the money that the FDA (Food and Drugs Administration) requires be spent to be able to launch hypertonic solution as equivalent to physiological serum.

Was it ever officially used?

The US military used it in the Iraq War and other military forces use it when they need to. The use itself is not prohibited. All the doctor has to do is prescribe a master formula. But it can’t be sold without an official license. The military uses it because there are logistical advantages. Instead of carrying two liters for each patient, they carry ¼ of a liter. In other words, the weight that goes in the stretcher-bearer’s backpack is eight times less. Furthermore, the product with 7.5% salt only freezes at – 3o C and by its very nature, it’s sterile, so it doesn’t spoil.

But even so it’s not commercial?

No, it’s not. I think that hypertonic has come to the end of its cycle as medication. But it’s still interesting as a research tool. Since 1980, major journals have published an average of one article per week on the subject. The lack of practical usefulness has not changed this pace.