Odair Leal / SesacreLiver transplant at a hospital in Rio Branco, Acre: the organ was brought from Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do SulOdair Leal / Sesacre

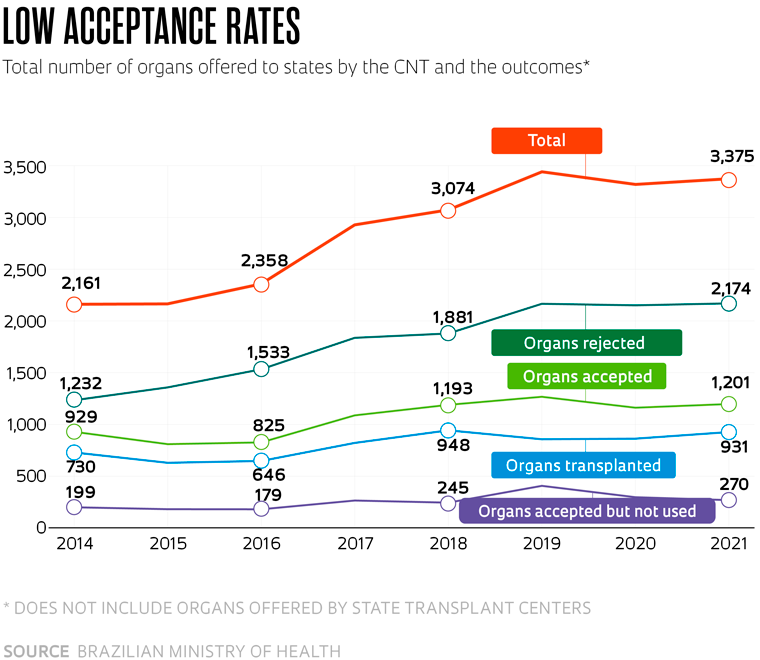

Most of the organs offered for transplantation in Brazil between 2014 and 2021 were not used, according to a survey carried out by technicians from the Brazilian Ministry of Health (MS) and researchers from the Health Sciences Teaching and Research Foundation (FEPECS) in Brasília, based on data from Brazil’s National Transplant Center (CNT) on the supply of solid organs — hearts, lungs, livers, kidneys, and pancreases — and the reasons why they were rejected. Of the 22,824 organs offered by the CNT in the period, 14,341 (63%) were rejected by the teams responsible for potential recipients. The results were published in April as a preprint that has not yet been peer reviewed.

More than half of the rejections (59%) were due to the clinical conditions of the donors, including old age, comorbidities, and infections, among other health problems. In 9% of cases, the organs were damaged or had morphological changes that prevented them from being used. Just 6% of rejections were associated with logistical problems, contrary to the common perception that one of the main obstacles to transplants is the need to transport organs between locations.

A significant proportion of the rejections (21%) occurred for unspecified reasons, which will be “analyzed in more detail,” says Patrícia Freire dos Santos, a nurse and technician from the Ministry of Health and lead author of the study, which did not include organs offered by state transplant centers. Preliminary data suggest that they experience problems related to the unequal distribution of specialist services for this type of procedure in the country. “Some states simply do not have transplant centers,” points out Freire, formerly a manager at the CNT.

She cites the example of Amazonas, which does not carry out heart transplants and therefore does not have its own waiting list for the organ. “Patients from Amazonas diagnosed with terminal heart failure are put on the waiting lists of states where the procedure is performed,” she explains.

Organ transplants in Brazil currently take place in a specific order, determined based on state, macro-regional, and national lists, in addition to other institutional mechanisms. According to Ordinance 2,600 of October 2009, every hospital with an intensive care unit (ICU), a referral emergency care department, or any that already performs transplants must have a committee responsible for identifying potential donors.

Whenever a new organ is identified, a compatible recipient is sought, starting in the state of origin — a kidney from a donor in São Paulo, for example, will first be offered to patients within the state. Regional lists are organized by state transplant centers, which cannot always find a compatible recipient. The transplant centers themselves sometimes reject organs, whether for not being suitable or for other reasons, such as not having the staff to collect the organ or an available operating room. These cases are then referred to the CNT, which will offer them to other states in accordance with the national waiting list. “The criteria used by local teams can vary,” explains physician Bernardo Sabat, head of the Pernambucana Abdominal Organs for Transplantation Team, who did not participate in the study. “Some accept certain organs from older people, for example. Others are stricter in that regard.”

Every heart identified for transplant in Amazonas, for example, goes straight to the national list — they are therefore very quickly offered to other states. “The ischemic time of a heart [how long the organ can live outside the human body without a blood supply] is only four hours, meaning it cannot be transported over great distances,” says Freire. A heart from Amazonas could be offered to nearby states, such as Acre, Rondônia, and Roraima, but these states also do not perform organ transplants. Meanwhile, surgical teams from states that do perform transplants, mostly located in the South and Southeast of the country, have to reject these organs because they know that they will not arrive in time. “This means that hearts from Amazonas are rarely used anywhere in the country.”

The same problem also occurs for other organs, such as the lungs, the transplantation of which is currently only performed in the states of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Paraná, Rio Grande do Sul, and Ceará. With an ischemic time of four to six hours, lungs are frequently rejected due to the origin being too far away. Unsurprisingly, the heart and lungs are among the solid organs with the highest refusal rate.

The Brazilian Air Force (FAB), private companies, and state security forces all provide use of their jets to help transport organs. “Even if we were able to reduce the journey time, the best thing would be for organs to be used in their own states of origin,” notes Freire. To make this a reality, it would be necessary to enable every state to carry out transplants, which would result in greater use of the organs available and reduce the national waiting list.

Sometimes, even organs that were initially accepted end up not being used. In the preprint published in April, Freire and her team reported that of the 8,483 (37%) organs accepted for transplantation, 6,433 (76%) were actually transplanted. The other 2,050 (24%), despite initially being accepted, were not used in the end. “It is possible that abnormalities are identified in the organ of the deceased donor during the surgery to remove it,” suggests Bernardo Sabat. “In that case, they are discarded.” According to Freire, there are also situations in which organs are compromised due to poor conservation.

Discarded organs are sent for anatomopathological examination, where they are processed and analyzed and a report is issued. “This document proves that the discarded organ was not later transplanted to a person not on the waiting list,” explains Sabat. “It is a way of preventing it from being diverted and sold.”

Despite the obstacles, the study led by Freire indicates that the supply of solid organs for distribution among Brazil’s states has been growing. There were 3,375 in 2021, an increase of approximately 56% compared to 2014. These figures, however, are far below the demand. According to data from the Ministry of Health, the national waiting list for solid organs contained 34,830 names at the end of 2022. In the same year, only 7,473 transplants were performed, demonstrating the shortfall between supply and demand.

When including individual state lists, the number of people waiting for an organ is 52,989, the highest it has been since 1998, according to the most recent data from the Brazilian Association of Organ Transplantation (ABTO). “Many transplant programs had to reallocate medical professionals to care for COVID-19 patients, resulting in a drop in the number of transplants in the country,” points out ABTO president Gustavo Fernandes Ferreira. Brazil performed 6,302 organ transplants in 2019, according to data from the latest Brazilian Transplant Register, published by ABTO and including organs offered by state centers. In 2020, when the pandemic began, this number fell to 4,826, and in 2021 it dropped even further to 4,777. In 2022, the figure began to rise again. “We are having to restructure the country’s entire capacity for organ donation and transplantation,” says Ferreira.

The number of families that refuse to authorize organ and tissue donation from relatives diagnosed with brain death, which had been declining since 2015, has begun rising again since 2021, reaching 46% in 2022, the highest percentage in the last eight years.

Brazil is internationally renowned when it comes to organ donation and transplantation — the service is provided free of charge by the country’s public healthcare system (SUS), which funds and performs more than 88% of all transplants in the country. About 12,000 transplant-related operations were performed by the SUS between January and November 2021. In 2020, around 13,000 such procedures were carried out. In absolute numbers, Brazil is the 2nd largest transplanter in the world, only behind the USA.

However, there is still plenty of room for improvement. Access is far from equitable and more efficient mechanisms are needed to reduce the obstacles to receiving the treatment, which primarily affect those living a long way from transplant centers. Training strategies have also proven insufficient at remedying existing problems, such as the low rates of notification for cases of brain death. “The medical profession needs to be more aware of the importance of pursuing a diagnosis of brain death,” emphasizes Paulo Manuel Pêgo-Fernandes, a physician at Hospital das Clínicas, part of the University of São Paulo’s School of Medicine (FM-USP).

In Brazil, organs can only be donated from individuals with diagnosis of brain death attested by a specialist and confirmed six hours later through clinical examinations and imaging. “It is done this way to protect the system and ensure there are no questions regarding reliability and the irreversibility of the diagnosis of death,” he explains. “It is a conservative approach, which in the end is too conservative, restricting transplant opportunities, with many doctors forgetting or failing to make this type of diagnosis because they are working in overcrowded hospitals.”

Republish