Sandra Jávera A pioneering study conducted in Brazil by Carolina Araújo, a professor at Institute of Philosophy and Social Sciences of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), obtained quantitative data on a phenomenon that researchers in the field of philosophy experience in Brazil and in several other places around the world: women are in the minority among students and faculty in this area of knowledge, and male predominance intensifies over the course of academic careers. This study compared the proportions of men and women at three different points in this career. Used as starting point was data from the Anísio Teixeira National Institute for Educational Studies and Research (Inep), according to which 38.4% of undergraduates majoring in philosophy in Brazil in 2014 were women.

Sandra Jávera A pioneering study conducted in Brazil by Carolina Araújo, a professor at Institute of Philosophy and Social Sciences of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), obtained quantitative data on a phenomenon that researchers in the field of philosophy experience in Brazil and in several other places around the world: women are in the minority among students and faculty in this area of knowledge, and male predominance intensifies over the course of academic careers. This study compared the proportions of men and women at three different points in this career. Used as starting point was data from the Anísio Teixeira National Institute for Educational Studies and Research (Inep), according to which 38.4% of undergraduates majoring in philosophy in Brazil in 2014 were women.

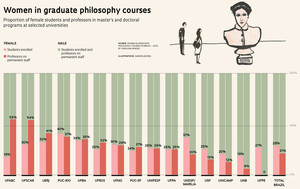

Araújo then compiled the names of 4,437 students and faculty at the 44 graduate programs in philosophy in Brazil as registered on the Sucupira Platform, the database maintained by the Brazilian Federal Agency for the Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (Capes) and the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), which provides data on the Brazilian academic community. She found that the proportion of women falls during graduate studies and over the course of their teaching careers. In 2015, of the 3,652 master’s and doctoral degree students, enrollment of women accounted for 28.45% of the total. But when figures on the permanent teaching staff in these programs are analyzed, 20.94% is composed of women. “In Brazil, women have a 2.5 times smaller chance than men of reaching the top of the academic career in philosophy,” concludes Araújo, who published her study on March 8, 2016, on the site of the National Association of Graduate Studies in Philosophy (Anpof).

As the study has shown, the situation in these graduate programs is not homogeneous. To cite two extreme cases, in 2015 there was not a single woman on the teaching staff of the programs at the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE) and the Pontifical Catholic University of Paraná (PUC-PR). According to philosophy professor Érico Andrade Marques de Oliveira, one of the coordinators of the UFPE program, women were always in the minority among professors at the institution, but the situation has taken a turn for the worse in recent years with the retirement of several female professors, who were replaced by men. “That pattern in the profile of philosophy professors is unsettling and does not help our efforts to attract female teachers. This is harmful, since the reflections of female philosophers do not necessarily coincide with the issues raised by male professors. In addition, philosophical thought often follows certain masculine standards,” he says.

Researcher Oliveira says that he personally strives to break up the excessive male presence at the university. “I make a point of always having at least one female student among my advisees in undergraduate research, because this program is decisive for being accepted into graduate programs. The shortage of women in the graduate programs is reflected in the competition for faculty positions, where the presence of women is rare. In some cases, there are no women candidates at all,” he says. An exception to this occurred in May 2016, when Loraine de Fátima Oliveira, then a philosophy professor at University of Brasília, passed the competitive exam for a position at UFPE. “There were three men competing against her,” says Érico Oliveira. Loraine Oliveira has not yet been accredited in the graduate program, which currently has 14 professors on permanent staff.

There is no scarcity of female voices in the graduate program in philosophy at the Federal University of the ABC (UFABC). According to the study, in 2015, half the professors in the program were women. Today, the situation has changed somewhat: women hold six of the 19 graduate teaching positions, a level that is still better than the national average. At the time the data was collected, the program had just been launched, and initially few men had been accredited. Luciana Zaterka, program coordinator, puts forward a possible explanation for the UFABC case: “the university is only 10 years old, and is working on a project that is still under construction. There are no departments. Professors teach undergraduate students various courses although their backgrounds are often in other areas – I myself also have a degree in chemistry,” she notes. “It is possible that this interdisciplinary approach, different from the compartmentalized structure of most universities, has helped to attract more women.”

There is no scarcity of female voices in the graduate program in philosophy at the Federal University of the ABC (UFABC). According to the study, in 2015, half the professors in the program were women. Today, the situation has changed somewhat: women hold six of the 19 graduate teaching positions, a level that is still better than the national average. At the time the data was collected, the program had just been launched, and initially few men had been accredited. Luciana Zaterka, program coordinator, puts forward a possible explanation for the UFABC case: “the university is only 10 years old, and is working on a project that is still under construction. There are no departments. Professors teach undergraduate students various courses although their backgrounds are often in other areas – I myself also have a degree in chemistry,” she notes. “It is possible that this interdisciplinary approach, different from the compartmentalized structure of most universities, has helped to attract more women.”

The University of São Paulo (USP), where 15% of its faculty is composed of women, and the University of Campinas (Unicamp), with 12.5%, are below the national average for graduate philosophy programs. “In the undergraduate area, we only have two young female professors actively working in the Philosophy Department. The number is a little higher in the graduate studies area,” says Maria das Graças de Souza, a professor at the USP School of Philosophy, Literature and Human Sciences (FFLCH). “Changing this situation will require individual efforts by professors to advise more women, but there have to be more women candidates. I have more boys than girls among my advisees,” she says.

The strong presence of male students and researchers makes philosophy an exception, since other areas of knowledge in the arts and humanities have opened their doors widely to women in recent decades. A study conducted by the Philosophy Department of Princeton University and published in 2015, showed that in the United States there are more women PhDs active in art history and psychology (around 70%) than in philosophy (less than 35%). “Philosophy is linked to a masculine academic environment, as is true of physics, mathematics and engineering,” says Monique Hulshof, a professor at the Unicamp Institute of Philosophy and Human Sciences. This situation is repeated in many countries. According to a study published in July 2016 by Eric Schwitzgebel from the Philosophy Department at the University of California in Riverside, in English-speaking countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia, gender disparity in philosophy is still significant, and although the involvement of women in this field of knowledge has grown in recent decades, there do not seem to have been significant gains since the 1990s.

The work brought together data from a variety of sources, such as the list of authors of prestigious philosophy journals, a study on PhDs prepared by the National Science Foundation, lists of speakers at conferences of the American Philosophical Association, and others. The study’s findings suggest that fields such as moral, social and political philosophy are closer to achieving gender parity than the other areas of philosophy. “Many of the most prominent women philosophers of the last 100 years are known primarily for their work in these areas,” wrote the researcher, referring to names such as Simone de Beauvoir, Hannah Arendt. Philippa Foot, Martha Nusbaum and Christine Korsgaard.

Sandra Jávera There is no simple explanation for the modest proportion of women in philosophy. A report published in 2011 by the British Philosophical Association (BPA) attributed the barriers to cultural phenomena, such as the belief that women are not attracted to certain subjects and the consolidation of stereotypes that stigmatize the researchers. There are those who point to historical causes. “There are not very many leading female figures in philosophy. As was the case with the sciences, from ancient times until the 19th century, women were not allowed access to writing, and this had an impact on philosophy and on literature,” says Maria das Graças de Souza. “There are general causes and specific causes. There are institutions that manage to attract more female students and professors to philosophy courses than others do, and there are teaching positions associated with the preparation of candidates for licenciaturas in philosophy in which there are more women.”

Sandra Jávera There is no simple explanation for the modest proportion of women in philosophy. A report published in 2011 by the British Philosophical Association (BPA) attributed the barriers to cultural phenomena, such as the belief that women are not attracted to certain subjects and the consolidation of stereotypes that stigmatize the researchers. There are those who point to historical causes. “There are not very many leading female figures in philosophy. As was the case with the sciences, from ancient times until the 19th century, women were not allowed access to writing, and this had an impact on philosophy and on literature,” says Maria das Graças de Souza. “There are general causes and specific causes. There are institutions that manage to attract more female students and professors to philosophy courses than others do, and there are teaching positions associated with the preparation of candidates for licenciaturas in philosophy in which there are more women.”

Of course, there are hypotheses to explain this phenomenon and the principal one among them is the idea that the academic environment is not very friendly to women. Monique Hulshof, of Unicamp, reminds us that philosophy specifically involves dealing with discourse and argument. “That argumentative function involves rhetoric and ability to speak with confidence and this is usually harder for women. I see this very clearly in female undergraduates. Many of them have difficulty in confidently taking a position, in developing more incisive arguments, and in producing more elaborate rhetoric. Obviously, it’s not a matter of not having the ability to do this, but women were raised in a cultural environment in which they were more encouraged to understand others than to impose their arguments,” she says. According to Hulsof, this problem is aggravated by the masculinized and masculinizing discourse adopted by academic institutions of philosophy. “The problem lies not only with women, whose discourse is insecure, but in the behavior of many men who interrupt them, ignore their arguments, and routinely dismiss their efforts,” she observes. “There are also other reasons for abandoning an academic career, such as the task of raising children, which generally falls on the woman, psychological and sexual harassment, and other reasons.”

In an article published on the Anpof site in October, Maria Isabel Limongi, a philosophy professor at the Federal University of Paraná, reinforces this hypothesis. “What is philosophy, if not an arena for disputes among the different perspectives of discourse? But here, it seems to me that women are at a disadvantage, since unlike men, they were never encouraged to assume authorship of their own discourse,” she writes. “In this game, they are usually intimidated, and when they aren’t, it is still hard for them. I didn’t go much beyond declaring the reasons that would have made me abandon the study of philosophy on the many occasions when I thought about it, and simply telling what I see here and there, among my graduate advisees, for example, many of whom are terrified of saying something stupid.”

Carolina Araújo’s interest in this subject was also inspired by her personal experience: she became a mother while she was working on her doctorate in 2002, at a time when scholarship recipients were not entitled to maternity leave. Her intention is to continue to draw attention to the gender disparity in philosophy. “We want Capes to monitor the gender divide in graduate study programs and provide updated data,” says Araújo. This would help to identify graduate programs and research groups that are not very accessible to female participation. “One action that would make an impact would be to distribute undergraduate research scholarships according to the proportion of men and women entering undergraduate studies, which is currently between 60% and 40%. This would make it more likely that this percentage would be maintained among those entering graduate school, and over the medium/long term, there might be a change in the scenario,” she says.

In other countries, the diagnosis of the problem has led to strategies for fighting it. The British Philosophical Association produced documents on good practices intended to reduce gender disparity in the philosophy career, with recommendations on the relationship between professors and students, and the distribution of academic positions. The strongest example of mobilization comes from the American Philosophical Association, which has a Committee on the Status of Women. This committee monitors the percentage of women in the philosophy career in the United States and publishes works by male and female philosophers who are considered to be underrepresented in the academic curriculum at universities.

Republish