A committee composed of representatives from nine governmental ministries has been tasked with a fundamental mission: to put an end to the public health problem of 12 infectious diseases associated with poverty in Brazil and to stop mother-child transmission of three diseases: syphilis, Chagas disease, and hepatitis B. The deadline is tight, set for January 1, 2030. Some of the ambitions of the Interministerial Committee for the Elimination of Tuberculosis and Other Socially Determined Diseases (CIEDDS) may seem utopian, but it has established a concrete deadline for the country to fulfill commitments made with multilateral bodies and to achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

“It’s not about eradicating the diseases entirely, but eliminating them as a public health problem and reducing them to more acceptable levels,” explains the committee’s coordinator, public health specialist Draurio Barreira, who is also director of the Ministry of Health’s Department for HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, Viral Hepatitis, and Sexually Transmitted Infections—the diseases under his umbrella are included in the CIEDDS mission, along with others such as leprosy, malaria, and schistosomiasis.

There are three diseases on the committee’s list that will not require such a great effort. Lymphatic filariasis, a chronic parasitic disease also known as elephantiasis, has not been recorded in the country since 2017. Transmitted by mosquitoes, it was last endemic in four municipalities in Pernambuco: Recife, Olinda, Paulista, and Jaboatão dos Guararapes. Trachoma, a type of conjunctivitis caused by a bacterium common in areas without proper sanitation, was present in 387 municipalities in 2019, but only the state of Ceará was above the threshold considered “acceptable.” The third example, onchocerciasis, is transmitted by insects and can cause blindness. It can be controlled with the antiparasitic drug ivermectin and there is only one endemic area in the country: the Yanomami Indigenous Territory.

As for the other illnesses, a timeframe of just seven years seems unrealistic given the scale of the task. Perhaps the most complicated example is geohelminthiasis, caused by intestinal parasites that live in soil, such as ascariasis and ancylostomiasis. The problem is greatest in North and Northeast Brazil, where intestinal blockages caused by roundworm infections can be fatal to children or leave them needing surgery. But its incidence is not even known—the last national survey of the issue was done in 2015.

Ricardo Funari / Brazil Photos / Lightrocket via Getty Images

Blood being taken from a suspected malaria patient at a mine in Pará: the goal is to reduce deaths from the disease to zeroRicardo Funari / Brazil Photos / Lightrocket via Getty ImagesThe idea of eliminating a set of diseases by 2030 was first floated at the beginning of the year, when Draurio Barreira’s department presented Health Minister Nísia Trindade with a proposal to reduce the burden of tuberculosis on the Brazilian population. “The minister challenged us to include leprosy and other diseases,” says the CIEDDS coordinator. Several are on the list of neglected diseases, which disproportionately affect poor people and countries, and thus attract insufficient investment in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

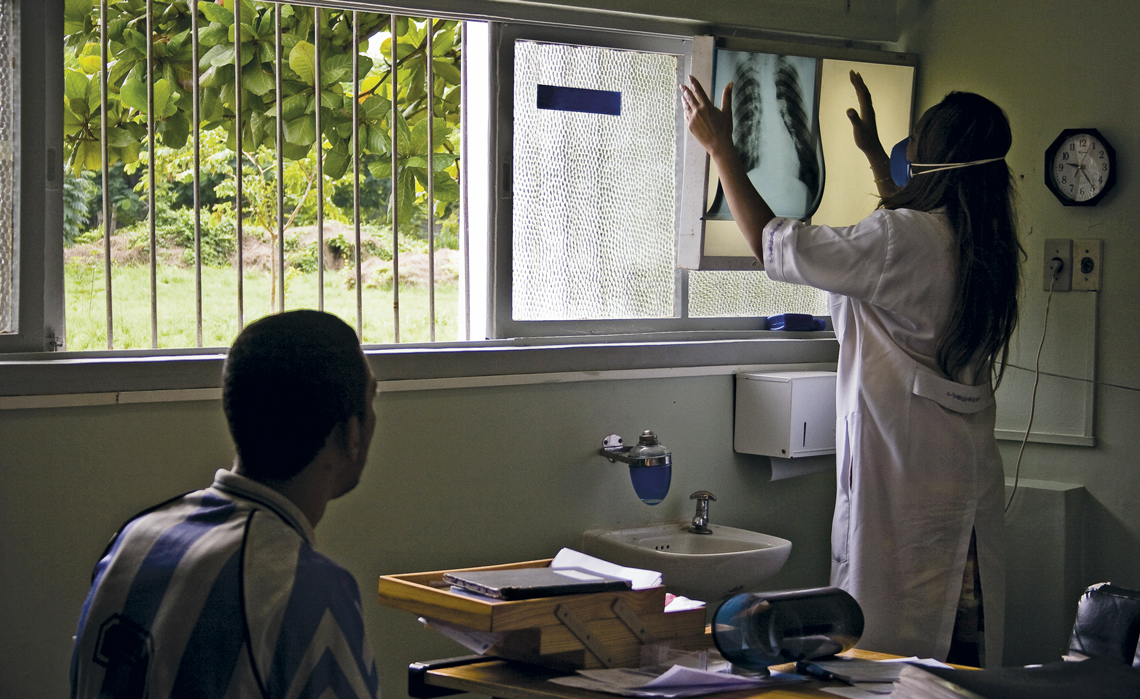

The goal for tuberculosis is bold: to reduce its incidence in the country to less than 10 cases per 100,000 inhabitants and the number of deaths to less than 230 per year. The most recent data, from 2019, showed 37 cases per 100,000 inhabitants and 4,500 annual deaths. Infectious disease specialist Marcos Boulos, from the University of São Paulo’s School of Medicine (FM-USP), is pessimistic. He points out that the BCG vaccine only protects against more serious forms of the disease in children and adolescents, and that the immunity it provides diminishes over time. “It is very difficult to eliminate tuberculosis when poor populations in urban centers live in such precarious housing conditions.” The situation is most complex in states such as Amazonas, Acre, and Rio de Janeiro, which have around 60 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, but there are places where the objective should be achievable, such as the Federal District, which currently only sees 10.5 cases per 100,000 inhabitants.

Boulos, however, does not underestimate the impact of well-coordinated government measures when it comes to eliminating diseases. “We had 8 million cases of malaria in Brazil in 1948, and five years later, in 1953, we had just 50,000,” he says. This occurred at a time when European countries were facing the disease and was the result of an international approach, based on treatment with chloroquine and the application of DDT pesticide on the walls of houses to eliminate mosquitoes. “When malaria ended in the developed world, funding to combat the disease in poor countries decreased, and the problem returned. We had more than 600,000 cases in the 1990s,” recalls Boulos. The goal of CIEDDS is to reduce the number to less than 68,000 per year and the number of deaths to zero by 2030. In 2020, there were 140,000 cases of malaria nationwide, and 51 deaths. “The political decision to eliminate malaria will mean removing illegal miners who have invaded Indigenous areas,” points out the infectious disease specialist.

The decision to create an interministerial committee was based on the need to involve different actors and sectors to combat the diseases. A representative from the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation will take part, with the aim of aligning research efforts funded by the federal government with the CIEDDS goals. The Ministry of Justice’s participation is essential to combat disease within the prison system. The Ministries for Social Development and Indigenous Peoples can help implement actions targeted at the homeless and Indigenous populations, both of which are vulnerable groups. “The cooperation between government ministries is welcome and I think it should even be extended to others, such as the Ministry for the Environment, because inadequate environmental management of disease vectors or reservoirs can lead to increased numbers of cases, and also the Ministry for Women, since women and children are the groups most affected by many of these diseases,” says Dr. Rosa Castália Ribeiro Soares, former head of the Ministry of Health’s National Program for Leprosy and Diseases Under Elimination.

Karina Zambrana / MS / OPAS / OMS

Agents from the Pan-American Health Organization at work in the Yanomami reserve, where onchocerciasis and other diseases are widespreadKarina Zambrana / MS / OPAS / OMSThe Ministry of Cities, responsible for federal sanitation projects, was not originally part of the CIEDDS team, but it is expected to join the committee soon. Investments in sanitation have been crucial to other countries eliminating these diseases and has already had an impact on another of the committee’s targets in Brazil: schistosomiasis, an infection caused by worms from the Schistosoma family, transmitted through contact with contaminated fresh water. It was one of the main endemic diseases in the country until the 1970s, and it is controlled through education and above all, access to sanitation and medication. “One of the committee’s objectives is to reinforce investment in sanitation in 175 municipalities that have a high burden of these diseases and need priority treatment,” says Barreira.

The incidence of viral hepatitis (A, B, C, D, and E) can also be reduced by investments in sanitation, but there are other strategies to consider. For hepatitis B, elimination is possible, since vaccine coverage in children is already close to 100%. The infection can still be spread, however, through sexual intercourse and needle sharing—in other words, deliberate actions by individuals at risk. For hepatitis C, the key is early diagnosis and treatment, because there is no vaccine.

Despite recent progress, some diseases targeted by CIEDDS will require better monitoring. There are still two million people in Brazil with Chagas disease, caused by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi, despite the fact that the primary means of transmission—the kissing bug (Triatoma infestans)—has been practically eradicated in endemic areas thanks to the replacement of wattle and daub houses, in which the insect proliferates, with other construction methods. However, transmission continues to occur through ingestion, when infected kissing bugs contaminate the processing of sugarcane or açaí juice. The CIEDDS team has been challenged to eliminate vertical transmission by testing pregnant women and prescribing medication when needed.

In addition to Chagas disease, CIEDDS will combat the vertical transmission of hepatitis B and syphilis, which will require increased prenatal diagnosis and medical treatment. Pregnant women infected with hepatitis B can be treated with an antiviral medication from the third month of pregnancy onward. The same approach is available for pregnant women with syphilis, who can be given benzathine penicillin to prevent transmission to the fetus. But this does not always happen. “Incredibly, the vertical transmission of syphilis is increasing in Brazil, because many doctors do not ask for blood exams during prenatal care,” laments Marcos Boulos. This problem has been solved for AIDS. “Obstetricians worry about getting infected with HIV when they deliver babies, so they never forget to make sure pregnant women are tested. As a result, we are close to achieving zero transmission, with 94% of Brazilian pregnant women tested,” says Barreira.

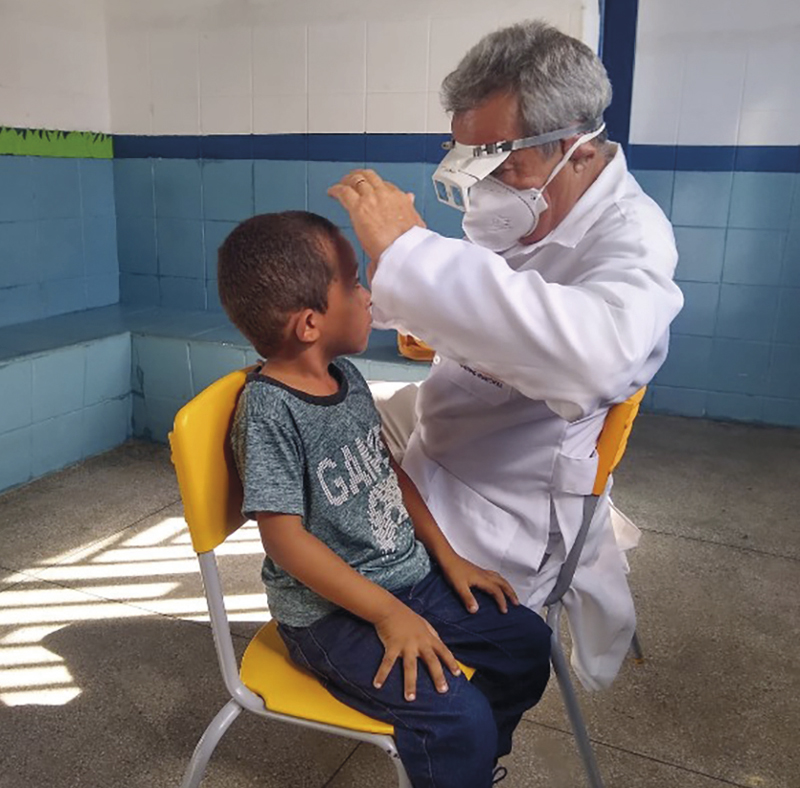

Crato Municipal Government

Trachoma prevention campaign at a public school in the interior of Ceará, a state where the eye disease still occursCrato Municipal GovernmentThe committee also intends to eliminate AIDS as a public health problem. The goal is to diagnose at least 95% of infected people, offer treatment to more than 95% of detected cases, and eliminate the viral load from at least 95% of treated individuals, thereby breaking the chain of transmission. The objectives for access to treatment and reduction of viral load have already been achieved, but the first link in the chain still needs to be resolved—currently, less than 90% of those infected in the country are diagnosed. The HTLV virus, which is related to AIDS, is transmitted in a similar way and causes a degenerative disease characterized by mobility problems, with most patients concentrated in just a few cities, such as Salvador, São Luís, and Recife. The national commission that rules on incorporating technologies into the country’s public health system (SUS) recently approved testing for pregnant women, which will increase the chances of elimination.

Leprosy represents one of the biggest challenges for CIEDDS, since recorded cases have not decreased in recent years, despite the expansion of care. “This is a disease from the Middle Ages. It’s shameful that we still have it in Brazil,” says Barreira. Brazil is only surpassed by India in leprosy cases. There were 19,635 new cases in the country in 2022, 7.2% more than in 2021. The states with the highest incidence were Mato Grosso (2,400), Maranhão (2,300), Pernambuco (1,800), and Bahia (1,700). The goals for 2030 are to interrupt transmission in 99% of Brazilian municipalities, completely eliminate the disease in 75% of municipalities, and reduce the absolute number of new cases by 30%. “The number of people left disabled by the disease has been falling thanks to the increase in diagnoses. But we need to go further and actively search for people who have had contact with infected individuals, so that we can administer chemoprophylaxis with a medicine called Rifampicin. This is the solution recommended by the WHO,” says Rosa Castália.

Luiz Carlos Dias, from the Chemistry Institute at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), says researchers also have a role to play in the effort to eliminate neglected diseases. “No new treatment has been developed for Chagas disease since the 1970s. Our industrial health complex needs to engage in the search for drugs and vaccines,” says the researcher, who is leading the Brazilian arm of an international consortium developing medicines for Chagas, visceral leishmaniasis, and malaria, with funding from FAPESP and organizations such as the Medications for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDI) and the Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV).

Infectious disease specialist Reinaldo Salomão believes the CIEDDS initiative is also important for a symbolic reason. It helps to break a vicious cycle that perpetuates the incidence of neglected diseases. “We have become accustomed to living with endemic diseases as if they were part of the landscape of the Global South, but they kill a huge number of people and only persist here because they affect disadvantaged populations,” he states. At the end of October, Salomão was one of the organizers of the FAPESP auditorium for the general assembly of the Global Research Collaboration for Infectious Disease Preparedness (GloPID-R), which brings together funding agencies that support research into new or emerging infectious diseases. “GloPID-R’s focus is on diseases with the potential to cause pandemics, capable of attracting funding and producing rapid responses from scientists, as occurred with the novel coronavirus. We need to use the lessons learned from COVID-19 to tackle neglected diseases once and for all.”

Republish