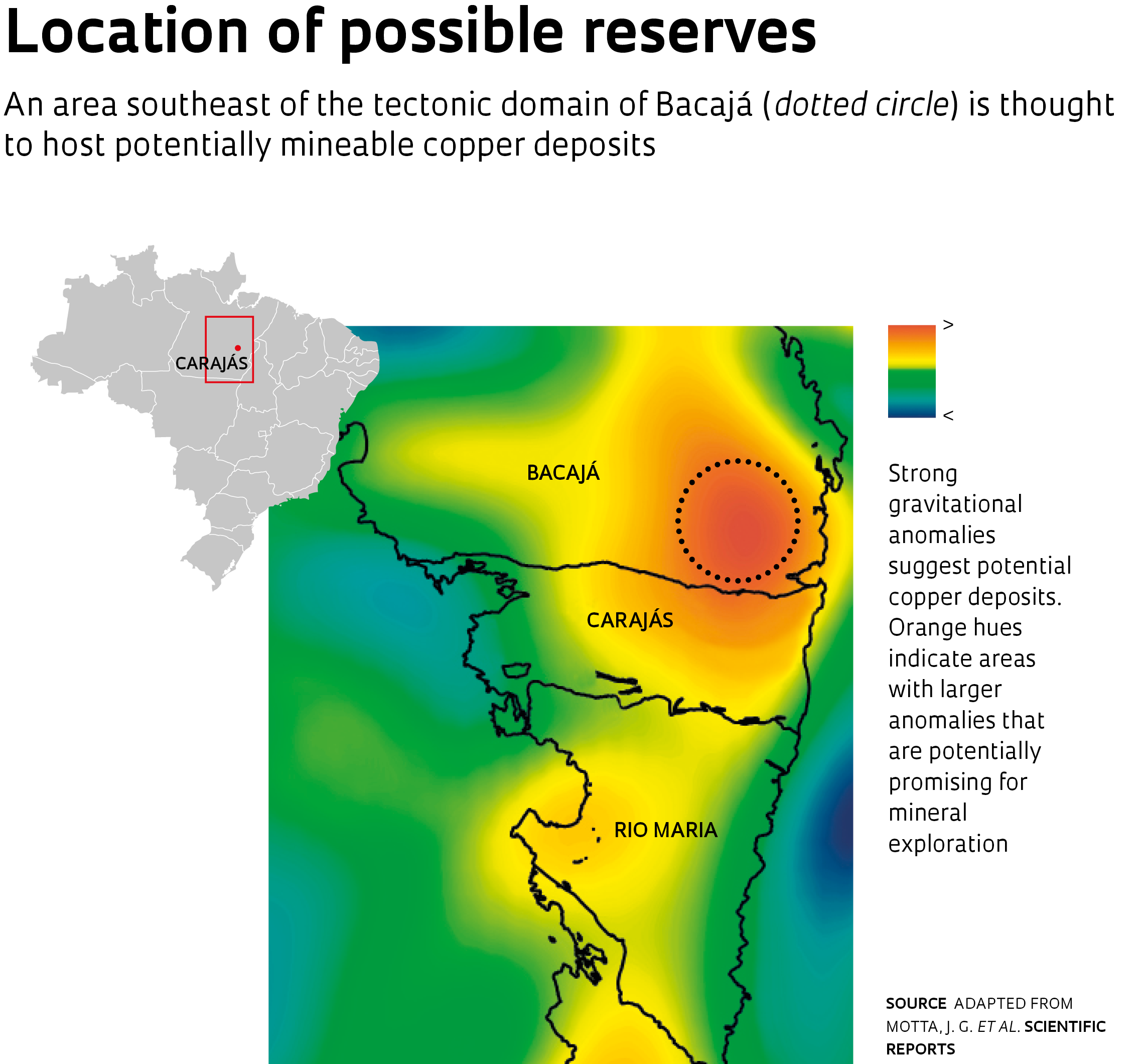

A detailed survey of variations in the earth’s gravitational field around Carajás, Brazil’s most important mineral province, in the state of Pará, suggests potentially mineable copper deposits are much vaster than previously thought. The findings were made by a team from the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) following a detailed investigation of the geology in the region using a combination of satellite data for South America and data from airborne surveys using small aircraft. Geologists Carlos Roberto de Souza Filho, a professor at UNICAMP and the principal investigator in a study that could redefine the mineral exploration landscape in the area, and his doctoral student, João Motta, mapped out potentially promising areas for copper exploration in an area poorly investigated by mining companies in the Bacajá region. The area extends more than 100 kilometers (km) from existing mines in Carajás, where proven reserves are to the tune of 3 billion metric tons.

The researchers first investigated tectonic data (subdivisions of tectonic plates) in Carajás, the first province to be fully covered by airborne gravimetric survey data at a regional scale in Brazil. When the Brazilian Mineral Research Company (CPRM), now the Geological Survey of Brazil, began conducting aerial surveys between 2013 and 2014, many experts already suspected that large gravity anomalies might be found in Carajás. Copper and iron deposits were then already being mined in the area. In 2017, after validation work had been completed and the embargo period had expired, the data was made public. “As soon as the results were released to the public, we were among the first academic groups to access the information,” says Souza Filho. “We had already observed anomalies in the gravimetric data and were curious to see what they looked like in the CPRM data. After spending days poring over the data, we were delighted to confirm that the anomaly was real and now corroborated by independently derived data at a different scale.”

After intersecting the CPRM data with satellite information—including data from the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Gravity Field and Steady-State Ocean Circulation Explorer (GOCE) mission and the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE), a joint mission of NASA and the German Aerospace Center—the UNICAMP team identified significant potential for the occurrence of copper in the tectonic domain of Bacajá, north of Carajás, which was then only party covered by airborne survey data. By combining the two types of data they were able to extend the coverage of the original CPRM map (see map on page 55). Fusing two different types of information together, with their different resolutions, and then analyzing that information in the context of known local geological conditions, was no trivial task. To validate his conclusions from the satellite gravity data, Souza Filho sought assistance from Carla Breitenberg, a researcher at the University of Trieste, in northern Italy, who had experience of applying this approach. The collaboration helped to ensure the data in the UNICAMP group’s final paper was sufficiently robust prior to publication on February 22, 2019 in Scientific Reports.

Gravity anomalies are more intense where rocks are denser or contain large volumes of metals, and can indicate the presence of mineral deposits

Variations in gravity

Studying gravity anomalies can provide important clues for mineral exploration—where rocks are denser or contain large volumes of metals at depth, the gravitational field is stronger. To detect these changes, geologists and geophysicists use instruments called gravimeters, which are essentially similar to the mass-spring systems used in classical physics. If a mass is hung on a spring, an increase in gravitational force will cause the spring to stretch proportionally and measurably. This is the basic principle behind the operation of all gravimeters, only modern instruments are extremely sensitive and sophisticated. Airborne gravimeters, for example, have compensation systems to offset the motion of the aircraft. To gather meaningful data, an airborne gravimetric survey needs to cover as large a number of observation points as possible.

In Carajás, CPRM surveyed an area about 400 km long by 300 km wide, or a total 120,000 square kilometers (km2), an area equivalent to half of São Paulo State. The survey was conducted along multiple latitudinal and longitudinal lines spaced 3 km apart, using two twin-engine airplanes equipped with gravimeters. The aircraft pilots covered a combined total of more than 58,000 km in the region, equivalent to a flight roughly one and a half times around the globe. Developed countries with a strong mining industry, such as the US, Canada, and Australia, have been fully mapped by airborne gravity surveys. In Brazil, however, these kinds of surveys are still prohibitively expensive—the CPRM investigation in Carajás cost approximately R$12.5 million—and no other surveys of this kind have yet been conducted since.

“Carajás was our starting point as Brazil’s most important mineral province, but further surveys are planned in Tapajós, Alta Floresta, and Amapá post-2020,” says Luiz Gustavo Rodrigues Pinto, head of the Remote Sensing and Geophysics Division at CPRM. The gravity data have also been supplemented by magnetic and gamma-ray spectrometric surveys in the region. These surveys measure respectively the magnetic field intensity and natural radioactivity of the crust, and provide insight into its geological structure.

Adapted from MOTTA, J. G. et al. Scientific reports

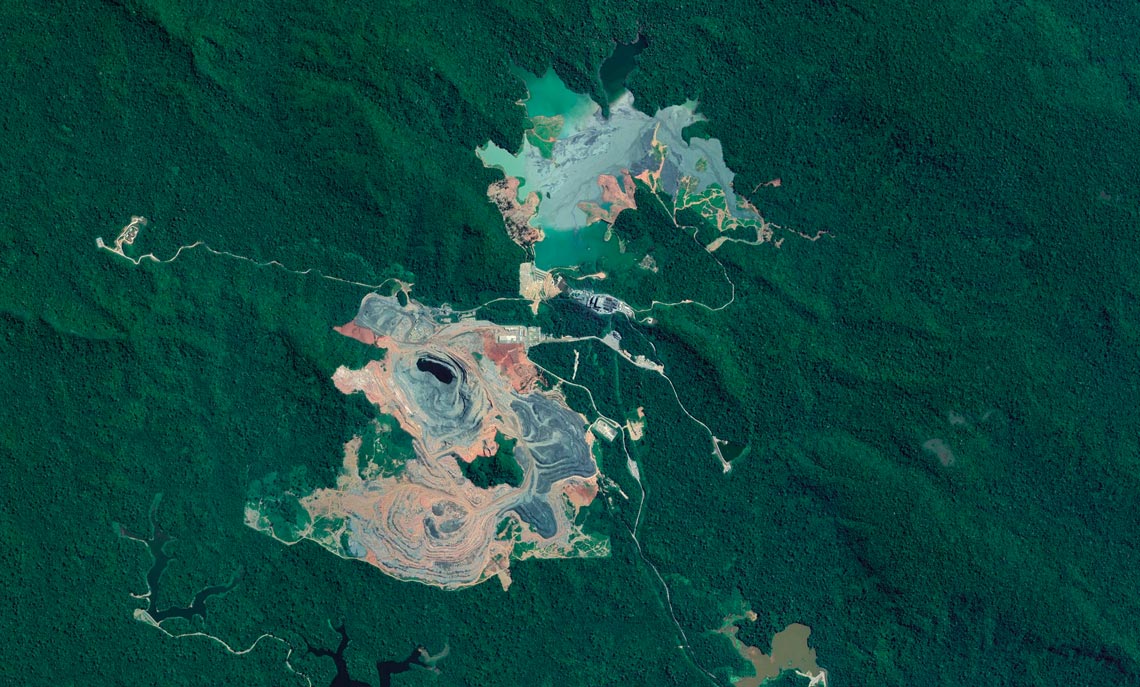

Salobo, one of the copper mines in ParáAdapted from MOTTA, J. G. et al. Scientific reportsMining and deforestation

While the UNICAMP and CPRM studies reveal there is potential for copper exploration north of Carajás, actual mine development is still a long way off. The time span from early exploration to the start of mining operations is typically at least a decade. If global copper prices rise, it may be that the exploration lifecycle would be shortened. “Demand for copper is on the rise,” says Souza Filho. “Emerging industries such as electric cars and cell phones require increasing amounts of the metal.”

But when it comes to mining in the Amazon, other concerns need to be taken into account, including environmental impacts and the risk of tailings dams failing as recently occurred in Mariana and Brumadinho in Minas Gerais State. And although mine development and operation causes less deforestation than farming, mining activity has inflicted scars on the landscape in the region. A 2017 study by a group led by Britaldo Soares-Filho, a researcher at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), estimates that 9% of deforestation in the Amazon can be attributed to mining.

The causes of forest destruction are not primarily the mines proper, but the supporting infrastructure they require—a mine operation is typically served by service roads, railroads, ports, tailings dams, and power transmission lines. While copper exploration potential north of Carajás exists only in theory at this time, conservation authorities still need to be alert, warns Soares-Filho. “The recent opening up of protected areas for mining creates added concerns,” he says.

In any case, the surveys needed to pinpoint where the copper deposits are in the region, if any at all, have not yet begun. The decision to develop a mine project needs to be preceded by an exploration phase involving detailed geological and geophysical surveys. Fieldwork would also be needed to identify target areas for deep core drilling. “What we have found so far is the potential,” says Soares-Filho. “There may be copper deposits there, but they may also have been consumed by other geological processes subsequent to their formation.” Gravity data provide clues to potential mineral deposits, but exploration drilling is needed for confirmation.

Scientific article

MOTTA. J. G. et al. Archean crust and metallogenic zones in the Amazonian Craton sensed by satellite gravity data. Scientific Reports. Feb 22, 2019.