Unidentified / Archive of Otto Lara Resende / Moreira Salles Institute CollectionTo the left, the writer Lúcio Cardoso, originally from Minas Gerais. Photograph taken in the 1940s in Rio de Janeiro, the city where he lived for 45 yearsUnidentified / Archive of Otto Lara Resende / Moreira Salles Institute Collection

“In my fight, what I seek to destroy and set on fire through the vision of an apocalyptic, unforgiving landscape is Minas Gerais. My enemy is Minas Gerais. My dagger is raised, with or without anyone’s approval, against Minas Gerais.” On November 25, 1960, writer Lúcio Cardoso (1912–1968), talking to journalist and literary critic Fausto Cunha of the Brazilian newspaper Jornal do Brasil about his new book, Diário I (Editora Elos), railed against his home state.

At the time, Cardoso had already released Crônica da casa assassinada (Chronicle of the murdered house; Livraria José Olympio Editora, 1959), a novel that attracted great critical acclaim. The story tells of the downfall of the traditional Meneses family in Vila Velha, a fictional town in rural Minas Gerais. Motivated by the book’s success on the literary scene, Cardoso was excited to do something he had dreamed of for a long time: he put together a collection of intimate writings dated from 1949 to 1951 in Diário I (Diary I), announcing that it was only the first volume in a series of five. The project, however, was never completed. Cardoso had a stroke on December 7, 1962, which left him paralyzed on his right side and seriously affected his speech. He went on to develop a career as a painter, using only his left hand. His writing was limited to drafts and fragments.

Now, however, the closest version of what he imagined has arrived in bookstores. With the air of a definitive edition based on the title Todos os Diários (All the diaries; Companhia das Letras) collates most of the writer’s nonfiction texts. The book was put together by Ésio Macedo Ribeiro, who studied the writer’s poetry for his master’s and PhD research at the University of São Paulo (USP). Ribeiro’s 2001 dissertation was one of the first academic papers to examine the verses of the author from Minas Gerais. In 2006, his work was released as a book, co-published by Edusp and Nankin Editorial. That same year Ribeiro defended his thesis, published by Edusp in 2011 under the title Poesia completa (Complete poetry).

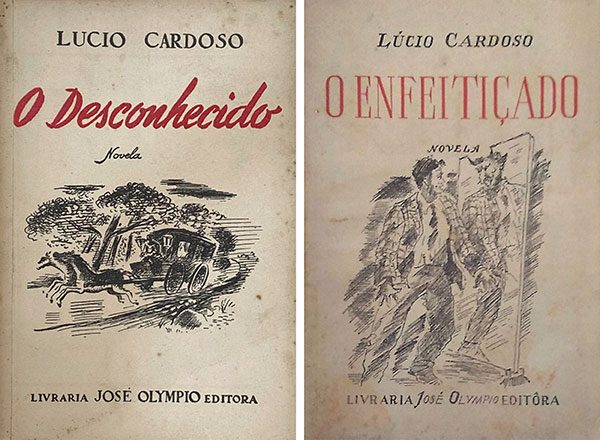

ReproductionBook covers of O desconhecido (1940) and O enfeitiçado (1954)Reproduction

Ribeiro is an independent researcher who has dedicated himself to Cardoso’s work over the last four decades. He made a previous attempt to fulfill the writer’s intentions to publish his diaries back in 2012. On that occasion, however, he admits that “there were some problems.” He points out issues with the index, for example, as well as in the notes and the existence of gaps due to difficulties locating certain journalism pieces. Commissioned by the publisher Civilização Brasileira, the diaries were published “very hastily,” due to the effort to coincide with the centenary of the author’s birth, he says. The venture was still a success, however, with the first edition selling out in just four days.

Composed of two volumes, Todos os Diários comprises not only Diário I, which the writer published during his lifetime, and Diário II, which was published together with the first diary in Diário completo (Complete diary), released posthumously in 1970 by the publisher José Olympio. Ribeiro’s compilation also includes previous personal writings by the author. Named Diário 0, these texts from 1942 to 1947 show that Cardoso was a reader of Dostoevsky (1821–1881) and the Bible, excerpts of which he analyzed and critiqued. The collection also includes texts from Diário não íntimo (Nonintimate diary), a column Cardoso wrote for the newspaper A Noite (Nightly) between August 30, 1956, and February 14, 1957. These were the gaps that Ribeiro regretted leaving in 2012. At that time, the researcher gained access to a complete collection of the columns shortly after the book was completed. Finally, the compilation includes a scattering of texts that were published in various other periodicals.

More than just an expanded version, the two volumes seek to correct a succession of errors and inaccuracies that have marred studies of Cardoso’s work for decades. It was Cássia dos Santos, a professor from the School of Arts at the Pontifical Catholic University of Campinas (PUC-CAMPINAS), who raised the alert. In her master’s research, carried out at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), she focused on how the writer’s novels published before Crônica da casa assassinada were critically received, from his debut book Maleita (Schmidt Editor, 1934) to O Enfeitiçado (The enchanted; Livraria José Olympio Editora, 1954). She defended her dissertation in 1997 and later published it under the title Polêmica e controvérsia em Lúcio Cardoso (Controversy in Lúcio Cardoso; Mercado de Letras, 2001), with funding from FAPESP.

Ruy Santos / Cinemateca BrasileiraCardoso, who also directed the film A mulher de longe (1949), starring Maria FernandaRuy Santos / Cinemateca Brasileira

At that time, Santos had already begun her PhD at UNICAMP, which she completed in 2005. Her doctoral thesis was published as a book last year: Um punhal contra Minas (A dagger against Minas; Mercado de Letras). For her research, which was funded by FAPESP, she visited the Casa de Rui Barbosa Foundation (FCRB), where the writer’s personal archive is stored, and found a folder of newspaper clippings. One was the undated interview given to Fausto Cunha. She then examined microfilms from the periodical collection at the National Library in Rio de Janeiro and discovered that the interview was from November 1960, meaning Diário I could not have been published in 1961, as previously thought.

This was the first error that Santos found in the Diário completo compiled by José Olympio. The researcher also realized that these flaws compromised the results of her own master’s research, which had been based on the compilation. More than “complete,” the collection released in 1970 was, in some respects, fictional. Santos told the story in a 2008 article in Revista do Centro de Estudos Portugueses, published by the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG). In the article, she scrutinized the José Olympio edition, which covered the periods from 1949 to 1951, corresponding to the edition by Cardoso, and from 1952 to 1962.

The list of errors described in the 2008 article is long. The researcher found, for example, that the dates of all the annotations from 1952 to 1955 had been changed in the book published by José Olympio, as well as some from the years 1956, 1957, 1958, and 1960. Notes that were already included in the edition released while Cardoso was alive reappear in later years. Errors that Santos found in a 145-page manuscript stored at the FCRB are reflected in the 1970 José Olympio book. The document “seems to be the first collection of the fragments that would give rise to the text of the Diário completo, writes the researcher in the article.

The confusion has hindered interpretations of important aspects of the writer’s process, in Santos’s opinion. Due to the alteration of dates, it was previously thought that Cardoso had alternated between writing the novel O viajante (The traveler), which remained incomplete, and Crônica da casa assassinada. In addition to creating an erroneous timeline, the manuscript used as a basis for the Diário completo is also full of notes and erasures. One of the changes introduced in the document was the omission of certain names, such as Graciliano Ramos (1865–1953), of whom Cardoso was “harshly critical,” says Ribeiro. According to the research he conducted for the current edition of the diaries, these changes were made by the writer Maria Helena Cardoso (1903–1977), who may have been worried about people feeling hurt by the unflattering notes written by her brother. About Ramos, author of Memórias do cárcere (Prison memories), a book that exasperated him, Lúcio Cardoso wrote on June 7, 1958: “The author’s modesty is false and what he saw and learned during his incarceration was limited and superficial.”

Cinemateca BrasileiraScene from Porto das caixas (1962)Cinemateca Brasileira

The writer’s contradictory personality is clear in the diaries. Cardoso was politically conservative, but socially liberal. As a homosexual, he lived in conflict with his Catholic faith. Despite abandoning the Church, he did not stop believing in God, as he states various times in his personal accounts. “Cardoso’s great existential drama lay in the clash between his sexuality and his Catholic upbringing in Curvelo, the town where he was born in the interior of Minas Gerais, which haunted him to the end of his life, including and especially in his diaries,” says Leandro Garcia Rodrigues, a professor of literary theory and comparative literature at UFMG.

As editor and a contributor of Lúcio Cardoso, 50 anos depois (Lúcio Cardoso, 50 years later; Relicário, 2020), the result of a colloquium held at UFMG in 2018, Rodrigues wrote an article on the brief and little-known exchange of missives between Cardoso and Mário de Andrade (1893–1945). His relationship with the poet from São Paulo was the subject of a second text by Rodrigues, also included in the compilation. In “Mário de Andrade, Reader of Lúcio Cardoso,” he presents Andrade’s notes on eight works by Cardoso that he had in his library. One was O desconhecido (The unknown; Livraria José Olympio Editora, 1940), a book that Andrade described as “full of common places.” About “Rosa Vermelha” (“Red Rose”), from Poesias (Poems), released in 1941 by the same publisher, he said: “One of the most perfect and beautiful Brazilian poems.” When looked at together, the two sets of work help shed light on how Andrade perceived Cardoso’s writing.

Ferdy Carneiro / Cinemateca BrasileiraPoster for A casa assassinada (1971), both films directed by Paulo Cezar Saraceni and based on stories by CardosoFerdy Carneiro / Cinemateca Brasileira

In a PhD thesis defended at USP’s School of Communications and Arts in 2022, editor Lívia Azevedo Lima analyzed three feature films directed by Paulo Cezar Saraceni (1932–2012) based on Cardoso’s stories: Porto das caixas (1962), A casa assassinada (The murdered house; 1971), and O viajante (The traveler; 1998), based on the unfinished novel of the same name published posthumously in 1973. “Unfortunately, the partnership started in Porto das caixas was interrupted by Cardoso’s stroke, but that didn’t stop Saraceni from continuing the projects,” says Lima.

The researcher also described the writer’s other cinematic forays as a film chronicler, screenwriter, and filmmaker. In 1949 he filmed A mulher de longe (The woman from afar). For a long time, the unfinished film was considered missing, until filmmaker Luiz Carlos Lacerda, the son of Cardoso’s producer, João Tinoco de Freitas (1908–1999), found a copy in the Cinemateca Brasileira film archive. In 2012, he made a documentary of the same name about the project. The making of A mulher de longe was stopped due to a lack of budget and experience, in addition to Cardoso’s impatience, as demonstrated in his own diaries: “Cinema is, of all the arts, the most laborious. […] A film is a recreated world […]. Unlike in novels, there are no laws and codes of subjective order […] but rather imperatives of the immediate order, principles of a tangible, objective, aggressive reality, like a rock with many edges.”

Cardoso was also a playwright and theater director. Some of his work includes O filho pródigo (The prodigal son; 1943) for the Teatro Experimental do Negro (TEN), by Abdias do Nascimento (1914–2011). These cinema and theater experiences, as well as his poetry, which is not widely known, deserve further academic study, says Ribeiro, pointing out that most of the research to date revolves around Crônica da casa assassinada. For Lima, the novel will continue to serve as a source for new studies, especially on issues of gender and sexuality. “The character Timóteo, for example, shares the conservative values of the rural oligarchy to which he belongs while at the same time wearing his late mother’s clothes and jewelry,” says the researcher.

The writer did not foresee the lasting success of the novel, which has been released in countries such as France, the USA, and the Netherlands. A 1959 entry in his diary explains that he was overcome by “a great melancholy.” He was convinced that like others, the novel would fall into “silence and disinterest.” His work never faced such problems, but he did. The writer fell ill less than two months after his last diary entry on October 17, 1962, when he wrote: “I want to love, travel, forget — I want life so terribly, because I don’t believe there is anything more beautiful or more terrible than life. And here I am: the things I love no longer listen to me, and I pass by with my stories, a strength without being strong, a prince, but in ruins.”

Projects

1. Chronicle of the murdered house: Critical reception and analysis of the novel by Lúcio Cardoso (nº 98/11282-5); Grant Mechanism Doctoral (PhD) Fellowship in Brazil; Supervisor Vilma Sant’Anna Areas (UNICAMP); Beneficiary Cássia dos Santos; Investment R$89,568.37.

2. Trilogy of passion: Saraceni as a reader of Lúcio Cardoso (nº 18/14804-8); Grant Mechanism Direct Doctoral (PhD) Fellowship in Brazil; Principal Investigator Mateus Araujo Silva (USP); Beneficiary Livia Azevedo Lima; Investment R$56,699.32.

Scientific articles

SANTOS, C. dos. Vicissitudes de uma obra: O caso do Diário de Lúcio Cardoso. Revista do Centro de Estudos Portugueses. vol. 28, no. 39, 2008.

Dossier

AMORIM, A. M. et al. Dossiê: 60 anos da Crônica da casa assassinada, de Lúcio Cardoso. Revista Opiniães. No. 17. 2020.