A new approach to the reforestation of native trees developed by researchers from the Department of Forestry Engineering of the Federal University of Viçosa (UFV), in Minas Gerais, is being tested in the area impacted by the socioenvironmental disaster caused by the breach of the tailings dam, of mining company Vale, in Brumadinho, in the Metropolitan Region of Belo Horizonte, in 2019. A further three areas close to tailings dams in the state are already being assessed for experimental implementation of the technique. The same occurs around the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Dam, in Altamira, in the state of Pará.

Named “DNA rescue and early flowering induction in native forest species,” the technique uses grafting and hormones prepared specifically for each species of tree. Its patent application was filed three years ago in the Institute of Industrial Property (INPI) and led to an article in the scientific journal Annals of Forest Research, in March 2020. “Trees such as yellow ipê [Handroanthus albus] or jequitibá [Cariniana legalis], which take between eight and 10 years to become adults, take one year to flower using the technique,” explains forestry engineer Gleison dos Santos, professor at UFV and responsible for the research. A tree is considered adult when it reaches reproductive age, meaning when it flowers, and creates flowers, fruits, and seeds.

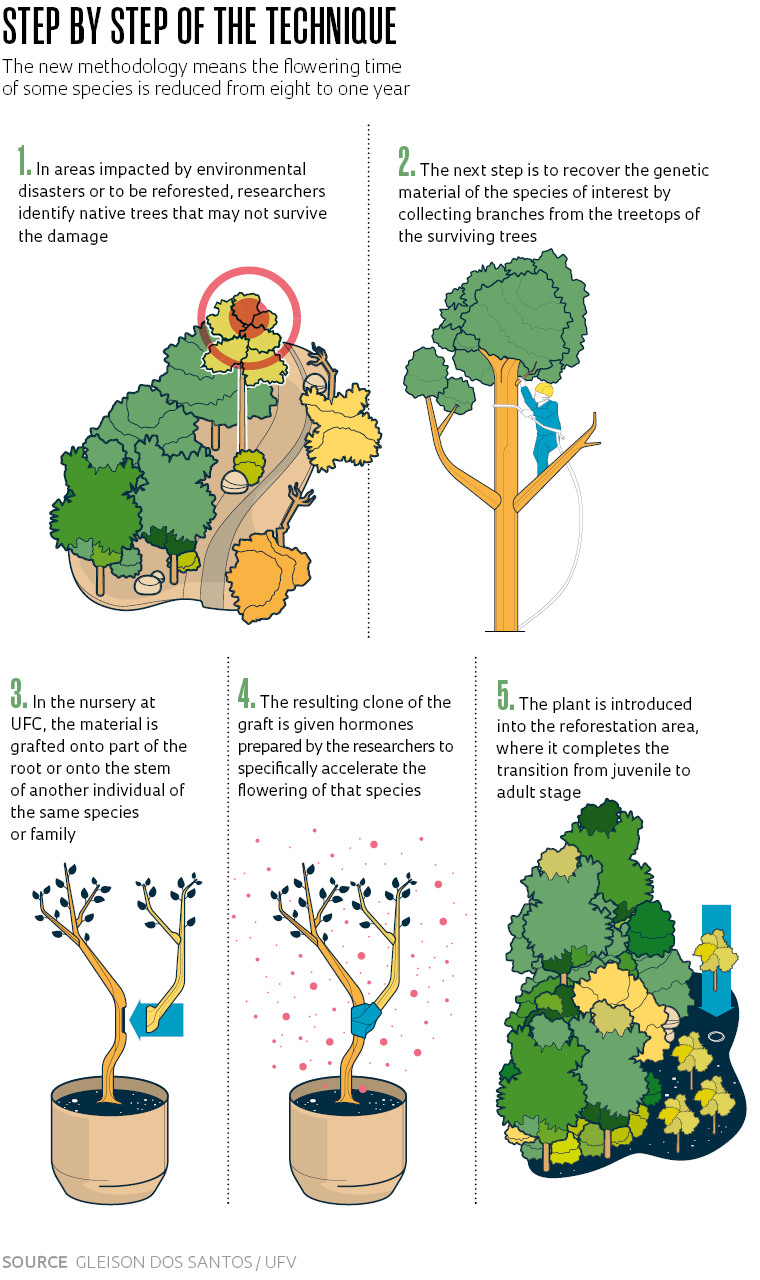

The work begins with an inspection of the impacted area by forestry engineers to survey the native species and identify examples of trees that could not survive the damage—in the case of Brumadinho, created by the mud with iron-ore tailings. The next step is collecting branches from the tree tops and taking them to the nursery at UFV, where they are grafted onto the root or stem of another tree of the same species or same tree family, producing a copy of the grafted tree, a clone.

In this process, the plant is subjected to a set of growth-regulating hormones, specifically prepared by UFV for each family of native trees, which accelerates the transition from young plant to adult stage. “This is the most difficult stage of the process, because it requires an adjustment of dosage and application periods. Each species has a recipe,” explains forestry engineer Luis Eduardo Aranha Camargo, of the Luiz de Queiroz College of Agriculture at the University of São Paulo (ESALQ-USP), who did not take part in the research.

VALEResearcher from UFV collects a sample of jequitibá-rosa for cloning in the laboratoryVALE

The next step is the introduction of the clones to the reforestation location. Flowering trees attract insects, bees, hummingbirds, rodents, and other pollinators and dispersers of seeds that in time will bear fruit. “From this moment, the ecosystem can be considered as restored,” says Santos.

Grafting, a method that joins parts of a plant to another in order to achieve better development, is common in agriculture, with widespread application in horticulture, fruticulture, and the production of trees with strong commercial appeal, such as pine and eucalyptus. The aim in such cases is generally to propagate genetically superior individuals so they can flower early, accelerating the crossbreeding.

The work of UFV, however, is innovative as it uses the technique in species of native trees at risk of extinction, which requires studies to understand the affinity between the rootstock and the branch of the tree that is being cloned, which is called a scion. This is how botanists, farmers, and forestry engineers call the parts from the trees that they wish to preserve. The tissues of the rootstock and scion are unified and, therefore, the transmission of water, mineral salts, photosynthesized compounds, and physiological characteristics take place normally.

Traditionally, forestry engineers prefer planting native tree seedlings as a form of recovering ecosystems impacted by human activity, fire, or other disasters. The tree seedlings are often obtained from nurseries in other regions in which the species is also native. However, these plants bought from outside need to adapt to the new ecosystem, something which is not free from risks, including premature death.

Forestry engineer Raul Firmino dos Reis, environmental analyst at Vale, points out that by introducing a clone created from genetic material recovered from trees that inhabit the impacted area, the technique developed in Viçosa has the potential of reducing the new plant’s risk of adaptation. “The clone carries the genome of the parent tree, which has a history of adaptation to that specific ecosystem. It is more apt at defending itself from the pests and parasites of the micro-region and is used to the local cycle of rains and droughts,” says Reis.