Sensors, fiber optics, satellite imaging, robots, and AI are all part of a growing arsenal of tools being deployed to track down hidden leaks in Brazil’s water mains. Historical waste figures make the urgency clear: a June 2024 report from the Trata Brasil Institute found that the water lost in distribution systems each year could supply 54 million people for a full year. Every day, that’s enough wasted water to fill more than 7,600 Olympic swimming pools, equivalent to 37.8% of all treated supply, according to Brazil’s National Sanitation Information System. Meanwhile, 32 million people still lack reliable access to clean water.

There is a silver lining: after six straight years of rising losses, 2024 saw the first decline—down from 40.3% in 2021. But the nation still lags far behind the federal target of keeping losses under 25% by 2033. “In most industries, a 25% loss rate would be unthinkable. Yet even that goal will be tough to reach,” says Maria Mercedes Gamboa Medina, a civil engineering professor at the University of São Paulo at São Carlos School of Engineering (EESC-USP). Leakage rates exceed 40% across much of northern and northeastern Brazil. In the state of Amapá, the figure is as high as 71%.

“The new Sanitation Framework has turned up the pressure to get leaks under control,” notes Fabrício César Lobato de Almeida, a professor of mechanical engineering at São Paulo State University (UNESP) in Bauru. The 2020 sanitation law (No. 14,026) outlines goals on achieving economic sustainability in service provision and on the use of technology to reduce operating costs and improve efficiency.

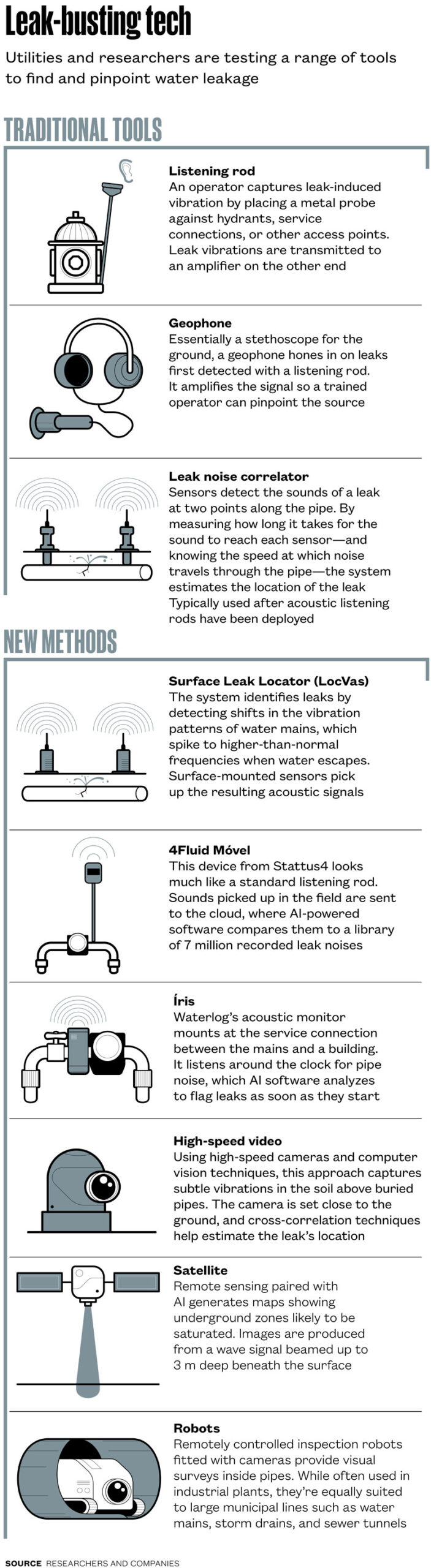

One initiative to achieve these goals is a Surface Leak Locator (LocVas) project that Almeida is leading in partnership with the São Paulo state water utility, Sabesp, with funding from FAPESP’s Research Partnership for Technological Innovation (PITE). The system identifies underground leaks by detecting shifts in the vibroacoustic signature of buried pipes, measured from the soil directly above them. When water escapes, it causes vibrations within a distinctive frequency range that depends on soil type, pipe material, and dimensions. Sensors placed at the surface pick up these signals—a noninvasive approach that avoids the need for excavation. The team plans to test the method on a variety of pipes and ground coverings—from grass to traditional Portuguese stone paving to asphalt.

LocVas builds on an established leak-detection approach based on cross-correlation, which also relies on capturing the vibroacoustic signal produced by escaping water. “In a leak-noise correlator, we measure signals captured by sensors placed at two points along the pipeline. By knowing how fast the sound of a leak travels and measuring the delay between those signals, we can estimate the leak’s position,” Almeida explains. The difference is that traditional noise correlators must make direct contact with the water main—usually through a manhole or by digging small access pits in the soil. The LocVas system, in contrast, is not required to be in contact with the pipe and can capture vibration signals at a distance. “A novel feature of our method is that it also estimates the routing of the pipe itself along with the leak’s location—something commercial devices don’t yet do,” says Almeida. The team published details of the technique in 2024 in the Journal of Physics: Conference Series.

Stattus4An engineer uses a 4Fluid Móvel smart listening rod to check for leaks in a municipal water lineStattus4

Launched in 2022 and expected to conclude in 2026, the UNESP-led project spans the full academic ladder—from undergraduates in scientific initiation to postdoctoral researchers—and has already led to several spin-off studies. One example is a master’s thesis by Bruno Cavenaghi at the Bauru School of Engineering (FEB), describing a project using cameras and computer vision to see the subtle vibrations of buried pipes through the ground above them. “We set the camera just inches from the ground, angled 10 to 15 degrees, to capture minute movements at that spot. Every pixel in the footage works like a tiny, virtual sensor,” explains Cavenaghi. In 2024, Cavenaghi earned the Young Professional Award from the Sabesp Engineers Association (AESabesp) for this work, which he showcased at the 35th National Conference on Sanitation and the Environment.

To test his approach, he used a leak-noise simulator developed at the university. “It’s the first in the world,” says Almeida, who supervised Cavenaghi. The bench simulator, Almeida explains, isn’t just a research tool—it is also a training platform for utility crews.

An array of leak-detection solutions

Acoustic detection is still the go-to method for finding water leaks. The most basic—and oldest—tools are listening rods and geophones. A listening rod, essentially a metal probe, is often used for an initial sweep: the operator presses it against hydrants, service connections (the junction between the mains and a building’s plumbing), or other access points to capture vibrations caused by a leak. For pinpoint accuracy, crews use geophones, devices that work much like a doctor’s stethoscope. Geophones amplify underground sounds but require a skilled ear to interpret the captured noise.

To speed up this process—and make it practicable even in regions short on trained personnel—Brazilian startup Stattus4 designed an intelligent, AI-driven detection system. In 2018, three years after its founding, the Sorocaba-based company launched 4Fluid Móvel with funding from the FAPESP Innovative Research in Small Businesses (PIPE) program. The device can be operated by workers with minimal field experience.

Noise captured through a listening rod is transmitted to the cloud, where artificial intelligence [AI] software compares it against a database of previously cataloged leak sounds. “We’ve logged over 7 million acoustic samples, which help our AI software detect potential leaks with better than 80% accuracy,” says cofounder and CEO Marília Lara. Some of Stattus4’s clients include major utilities such as Sabesp; Copasa in Minas Gerais; Sanepar in Paraná; and the Águas do Brasil Group, which serves 32 municipalities across São Paulo, Minas Gerais, and Rio de Janeiro.

Founded just four years ago in São Paulo, Waterlog is also leveraging AI to detect the sound signatures of leaks. Chemical engineer and cofounder Fernando Loureiro Pecoraro says Brazil’s amended sanitation framework led to a collaboration with utility companies to develop a high-tech anti-leak system, called Iris. “Its key advantage is real-time monitoring,” Pecoraro says. “Mounted at the service connection, the system listens for noise in the network and flags a leak the moment it happens. To pinpoint the exact location, you still need other tools, like geophones.”

While acoustic methods dominate, the leak-detection market offers a growing menu of technological options. Choosing the right one often comes down to cost-effectiveness—a calculation that varies with local economic conditions and available technology. According to Cícero Mirabô Rocha, a civil engineer in Sabesp’s Operational Development division, the utility routinely evaluates pitches from tech companies. “We always start with a trial,” he says. “If it works, it goes into our toolbox. But there’s no silver bullet—the only thing that works is a combination of techniques.”