It is a hot topic on which people tend to take an extreme position. That and the fact that it is illegal in Brazil could explain why abortion remained a hidden issue for such a long time and has only recently begun to be more discussed. Despite being prohibited by law and frequently subject to moral and religious condemnation, the fact is that it occurs, it is common, and it is almost always carried out unsafely (without the help of health professionals or adequate means), which puts women’s lives at risk. The most recent and reliable estimate, obtained using methods to protect the respondents’ identities, suggests that around 500,000 abortions are performed in Brazil every year. Almost half of the cases (43%) led to complications that required the woman to be admitted to a hospital or emergency room to complete the procedure.

“Abortion is a public health issue that affects regular Brazilian women, in particular the youngest and most vulnerable, such as Black women,” says Debora Diniz, an anthropologist from the University of Brasília (UnB), one of the coordinators of the National Abortion Survey (PNA). Currently in its third iteration, the survey, repeated on average every five years, attempts to provide an idea of the scale of the problem in Brazil. In the most recent PNA, interviewers visited 125 Brazilian municipalities in November 2021 to collect sociodemographic information from 2,000 women aged between 18 and 39 years old. Each participant was also given a questionnaire containing seven questions about abortion, which they completed and deposited into a sealed box to maintain confidentiality. The women, all representative of Brazilian women of childbearing age who can read and write and live in cities, were randomly selected to take part in the survey.

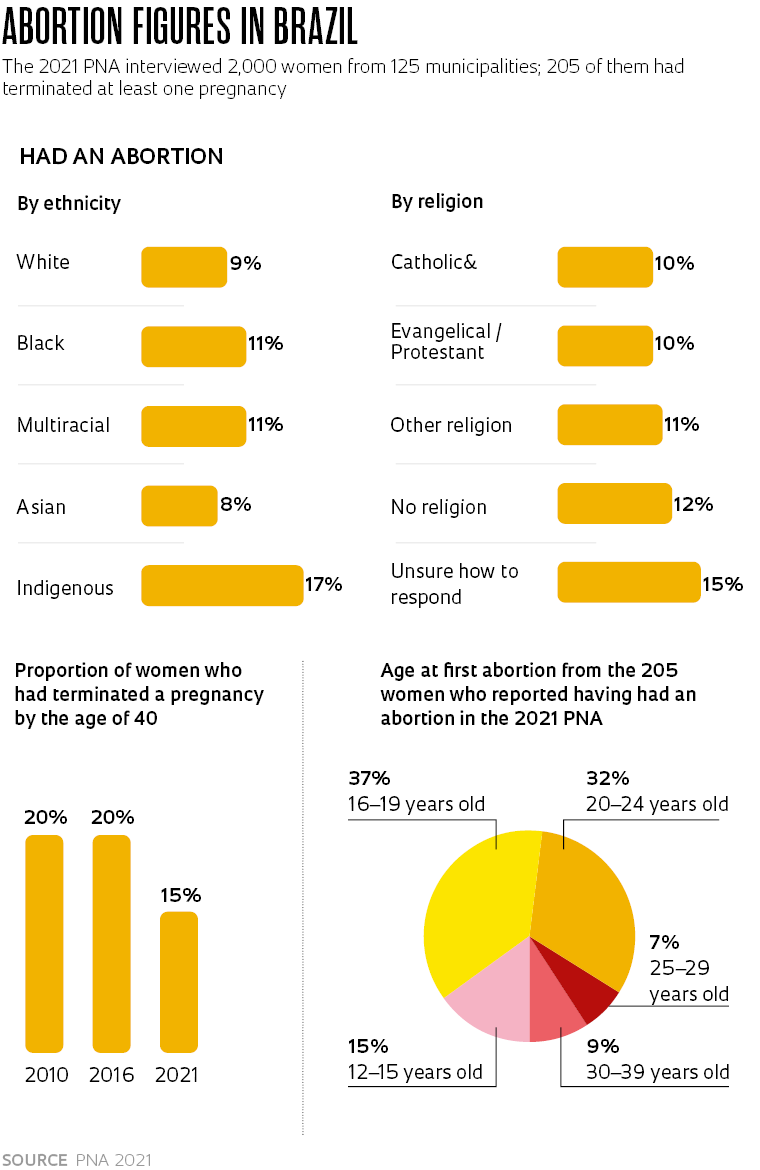

The results, accepted for publication in the journal Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, show that abortion is a common occurrence among Brazilian women: one in seven women aged 40 has had at least one abortion. “Any problem that affects such a large proportion of the population is a huge health issue for a country,” emphasizes sociologist Marcelo Medeiros, a visiting professor at Columbia University, USA, and coauthor of the study.

This proportion, however, appears to be decreasing. It was approximately 20% in the 2010 and 2016 surveys, but dropped to 15% in 2021. Although the respondents were aged between 18 and 39, the researchers use a statistical tool to project the abortion rate at age 40 and correct any distortions in the data caused by the aging of the population and the fact that abortion is a cumulative phenomenon.

In 2021, for the first time, the survey evaluated the age at which participants had their first induced abortion and found that the problem starts early in the lives of Brazilians: 52% of those who had interrupted a pregnancy did so before the age of 19. “Pregnancy is a major social and economic problem for young women in this age group. It prevents them from continuing their studies, jeopardizes professional training, and limits access to the job market,” explains Medeiros.

According to the PNA, those seeking clandestine abortions in Brazil are regular women. Every edition of the survey has shown that an almost equal proportion of white, Black, and multiracial women have had an abortion. In 2021, about 10% of women in each of these groups had terminated a pregnancy at some point in their lives. Also close to 10% was the proportion of Catholic, Evangelical, Protestant, and atheist women who have had an abortion (see graphics).

Although the proportion of women undergoing abortions is trending downward, the numbers are viewed with caution by the researchers, who believe the drop may be smaller than it appears. The survey’s margin of error is two percentage points and there can be statistical fluctuations between one version and the next, which would bring the values closer together. It is also possible that the data are influenced by a change in population structure. In the 11 years that separate the first PNA and the last, the Brazilian fertility rate dropped from almost 1.9 children per woman to 1.5, and fewer pregnancies would mean fewer abortions. Some studies also suggest there has been an increase in the use of long-term contraceptive methods in Latin America.

If the changes recorded by the three PNAs is real, it may indicate that Brazil is following a trend seen in more developed countries in recent decades, contrary to the direction taken in the rest of South America. Abortion statistics recorded in 186 countries between 1990 and 2014 show that in a quarter of a century, the pregnancy termination rate has dropped significantly in more developed nations—falling from an average of 46 abortions for every 1,000 women of reproductive age to 27 per 1,000. According to data published in the journal The Lancet in 2016, the rate grew from 43 to 47 per 1,000 women in South America in the same period.

Intentional terminations are common all over the world. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 73 million induced abortions occur each year, equal to one-third of all pregnancies. The international health agency considers the procedure safe “when carried out using a method appropriate to the pregnancy duration and by someone with the necessary skills.” In 45% of cases, however, these conditions are not met and the woman’s life is put at risk. Almost all of these unsafe abortions (97%) occur in developing countries.

In Brazil, according to the trends identified by the three editions of the PNA, the severity of health complications resulting from abortion is decreasing. In 2010, 55% of women who had an abortion ended up being hospitalized. By 2021, this figure had fallen to 43%. This is still a significant number of women, representing about 200,000 hospitalizations per year. “This has a health impact on women and a cost impact on the public health system,” stresses Diniz.

“The decrease in the rate of complications suggests a possible transition from the use of more dangerous methods involving manipulation of the uterus, such as the use of needles and other objects, to other safer strategies using illegally obtained drugs,” says gynecologist and obstetrician Luiz Francisco Baccaro of the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), who was not involved in the PNA. Baccaro coordinated Brazil’s participation in a recent WHO study that analyzed the severity of abortion-related complications in 70 hospitals in six Latin American countries (20 of them in Brazil). Published in the magazine BMJ Global Health in 2021, the results suggest that most cases that lead to medical involvement in Brazil and Peru are less severe than those treated in Argentina, Bolivia, the Dominican Republic, and El Salvador (the data were collected before abortion was legalized in Argentina at the end of 2020). In Brazil, 83% were mild complications, such as light bleeding, and 14% were moderate, most often heavier bleeding.

Although the degree of complications varies between countries due to the different characteristics of their healthcare systems, the WHO estimates that 13% of all maternal deaths—those that occur during pregnancy or as a result of its termination—are the result of unsafe abortions. Experts say the solution to the problem is to ensure access to reproductive planning to avoid unwanted pregnancies and to offer safe conditions for terminating a pregnancy, something that would require a change in legislation in Brazil.

Brazilian law classifies abortion as a crime against life. Women who choose to terminate a pregnancy face up to three years in prison, and anyone who helps (whether they are a medical professional or not) can be sentenced to up to 10 years. The 1940 law establishes just two conditions in which abortion is permitted: for pregnancies resulting from rape or when the procedure is the only way of saving a woman’s life. In 2012, a decision by Brazil’s supreme court also authorized abortion in cases of anencephaly, when parts of the brain and skull do not develop and the baby would be unable to survive after birth.

Despite these exceptions, the proportion of legal abortions is much lower than might be expected. In a study published in Cadernos de Saúde Pública in 2020, Bruno Cardoso, a public health physician from Rio de Janeiro’s Municipal Health Department, and colleagues analyzed data on births, deaths, and hospitalizations in the Brazilian public healthcare system (SUS) from 2008 to 2016 and found that about 1,600 abortions were performed per year on medical or legal grounds. This is much lower than the number of pregnancies resulting from rape (estimated at 18,000 per year) that could be legally terminated.

Regulations issued by the Brazilian Ministry of Health in 2005 offer guidance to health professionals on how to deal with and treat abortion cases. According to the document, “safe abortion and related treatment for reasons legally permitted in Brazil constitute a woman’s right, which must be respected and guaranteed by health services.”

The regulations, however, do not do enough to ensure the service is offered to the public even in the situations provided for by the law. During her PhD at the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC), psychologist Marina Gasino Jacobs, under the supervision of public health specialist Alexandra Boing, searched three SUS databases for information on establishments registered to perform legal abortions or that had performed legal abortions in 2019. It found 290 health services, located in just 200 of Brazil’s 5,568 municipalities. According to data published in Cadernos de Saúde Pública in 2021, 40% of them were located in the southeast of the country. “In 2019, 58.3% of women of childbearing age lived in municipalities where legal abortion was not offered,” the authors wrote.

The important question is how to reduce abortions, especially unsafe ones. The answer, according to experts on the subject, lies in educating the public on safe sex and informing them about contraception and making it available. “Everyone has sex. We have to stop treating this topic as a taboo and start talking at school, on television, at church, about how to prevent pregnancy,” says Medeiros. He also emphasizes that men need to assume half of the responsibility for the issue of pregnancy and safe sex. “If men used condoms every time they had sex, the unwanted pregnancy rate would fall to close to zero, and abortions would consequently decrease,” he concludes.

Experts also argue that abortion needs to be decriminalized. Several studies indicate that making the procedure legal and offering women the possibility actually leads to a reduction in the number of abortions. “The number drops because women are welcomed and given access to contraceptive methods and advice on how to prevent unwanted pregnancies,” says Rosa Domingues, an epidemiologist from the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation in Rio de Janeiro and the author of recent reviews on legal and illegal abortion in Brazil. “Criminalizing abortion does not solve the problem. It just makes it unsafe,” says Diniz.

Scientific articles

DINIZ, D. et al. National Abortion Survey – Brazil, 2021. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. In press.

SEDGH, G. et al. Abortion incidence between 1990 and 2014: Global, regional, and subregional levels and trends. The Lancet. July 16, 2016.

ROMERO, M. et al. Abortion-related morbidity in six Latin American and Caribbean countries: Findings of the WHO/HRP multi-country survey on abortion (MCS-A). BMJ Global Health. Aug. 2021.

CARDOSO, B. B. et al. Aborto no Brasil: O que dizem os dados oficiais? Cadernos de Saúde Pública, Vol. 36, supplement 1. 2020.

JACOBS, M. G. & BOING, A. C. O que os dados nacionais indicam sobre a oferta e a realização de aborto previsto em lei no Brasil em 2019? Cadernos de Saúde Pública, Vol. 37, no. 12. 2021.

Republish